Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly Asks DOJ for Signs of Life

Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly granted Dan Richman his request for a Temporary Restraining Order, preventing the government from snooping in his stuff, one that goes through Friday. And while I agree with Gerstein and Cheney (and Bower and Parloff) that it could have the effect of thwarting another indictment of Jim Comey — indeed, it may undercut an attempt to stonewall Richman — I find KK’s order interesting for other reasons.

Partly, it’s the way she’s demanding signs of life from DOJ.

Judge KK attempts to forestall a stonewall

As a reminder, Judge Cameron Currie threw out the indictment against Jim Comey on November 24, the Monday of Thanksgiving week. Two days later, the day before Thanksgiving, Richman cited that dismissal and the expired Statute of Limitations in his bid to get his data back. As far as I know, no one noticed it until Anna Bower pointed to it on Tuesday.

Notably, Richman attached the warrants used to obtain his records as sealed exhibits.

The same day Bower noted it (the day it was assigned), December 2, Judge KK issued an order, half of which dealt with Richman’s sealing request, which she provisionally granted. But she also told him that if he wants to keep the government out of his data, he needs to get a Temporary Restraining Order. Her order emphasized that that request must submit some sign of life from DOJ.

Finally, Petitioner Richman’s 1 Motion requests that this Court “issue a temporary restraining order enjoining the [G]overnment from using or relying on in any way” the materials at issue in his 1 Motion while this matter is pending. Consistent with Local Rule of Civil Procedure 65.1, it is ORDERED that Petitioner Richman shall file his application for a temporary restraining order by separate motion, accompanied by a certificate of counsel that either (1) states the Government has received actual notice of the application and “copies of all pleadings and papers filed in the action to date or to be presented to the Court” in connection with the application; or (2) identifies “the efforts made by the applicant to give such notice and furnish such copies.”

A Certificate of Service Richman filed later that day explains part of the reason KK made that order: For some reason, the motion was not docketed. So, Richman attorney Mark Hansen explained that he formally served Jocelyn Ballantine and DC USAO on December 1.

This Corrected Certificate of Service corrects the service date listed for the public redacted Motion for Return of Property and accompanying attachments, see ECF No. 1 at 3, and the sealed version of that Motion with accompanying attachments, see ECF No. 2, from November 26, 2025, to December 1, 2025. Although Petitioner filed those papers on November 26, 2025 and intended to serve them on that date, the filings were not docketed at that time. I promptly caused the filings to be served on counsel for respondent upon receiving notification from the Clerk’s Office, on December 1, 2025, that the filings had been accepted for submission and docketed.

But to comply with the other part of her order, Richman’s attorneys also included the emails they exchanged with Ballantine. And among the things those emails showed is that after agreeing to attorney Nick Lewin’s midafternoon December 3 request to respond by close of day on December 4,

Based on the government’s use of such property in connection with the Comey case (as described in Judge Fitzpatrick’s November 17, 2025 opinion), we are concerned that, absent a TRO, the government may continue to use the property in a manner that violates Professor Richman’s rights – particularly in light of recent news reports that the DOJ may seek a new indictment of Mr. Comey. However, if the government has no such intention and will agree to refrain from searching, using, or relying in any way upon Professor Richman’s property pending resolution of the Rule 41(g) motion, that would address our concerns and obviate the need for a TRO.

Please let us know the government’s position by COB tomorrow.

[snip]

Nick,

Thanks for your email. I will reach out to the appropriate people at DOJ with your request and will respond to you tomorrow by COB.

Jocelyn

Ballantine had not responded by 9PM on December 4.

Hi Jocelyn,

Did you get an answer? Please let us know.

Ballantine had a good excuse: she was busy prosecuting accused pipe bomber Brian Cole. Nevertheless, when she did respond at 9:12PM Thursday night, she said that her leadership — Jeanine Pirro — had already engaged with DOJ leadership (Bondi spent part of Thursday with Pirro bragging about the pipe bomber arrest), but she would not have an answer until “early next week.”

Thank you so much for the prompt. I met with my leadership today, and they have engaged Department of Justice leadership. I have also shared your pleadings and request with the prosecutors who handled the Comey prosecution out of EDVA.

I do not have an answer for you this evening, but I expect to have one early next week.

That’s what led Richman to file his motion for a TRO, maybe around 10PM Friday night. Judge KK responded just under a day later.

Her order specifically ruled that DOJ knows about Richman’s request.

Third, the Court finds that the Government has received actual notice of Petitioner Richman’s [9] Motion, ensuring that the Government is positioned to act promptly to seek any appropriate relief from this Order. Specifically, counsel for the Government may move to dissolve or modify this Order immediately upon entering an appearance, and the Court will resolve any such motion “as promptly as justice requires.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(b). Under the circumstances, the Court will allow and consider such a motion at any time upon contemporaneous notice to counsel for Petitioner Richman. See id. (providing that such a motion may be filed “[o]n 2 days’ notice to the party who obtained the order” or “on shorter notice set by the court”).

And barring the government requesting a different schedule, Judge KK’s order set up the following schedule:

- Richman should “promptly” serve Judge KK’s order and everything filed in the docket to Pam Bondi (KK identifies Bondi by title specifically).

- By noon on Monday, “the Attorney General of the United States or her designee” must confirm “the United States,” so everyone!, is in compliance with KK’s order not to “access … share, disseminate, or disclose” Richman’s data “to any person.”

- By Tuesday at 9AM, DOJ must respond to both of Richman’s requests.

- He must reply by 5PM that day.

- The order will expire at 11:59PM on Friday night if Judge KK has not issued an order first.

If DOJ follows Judge KK’s order, then it will have the effect of:

- Slightly accelerating the response deadline for DOJ, which may have been due sometime on Tuesday anyway, while dramatically accelerating Richman’s reply, which is now due that same day.

- Flip the default status of Richman’s data, restricting DOJ from accessing it before Judge KK issues an order rather that allowing them to access it until any such order is in place.

In other words, the government can’t stall Richman’s effort in a bid to use the data in the interim. If DOJ follows the order, then it would prevent DOJ from using the data to get a new indictment before such time as Ballantine responds, “early next week.” Unless DOJ got an indictment on Friday with hopes of a big show arrest tomorrow morning, then KK would have thwarted any effort to stonewall Richman’s assertion of his rights.

If DOJ blows off the order, it’ll make it even easier for Comey to argue any indictment is malicious (unless, of course, he has to argue that to Aileen Cannon).

Did Judge KK smell a rat?

That’s the logistics of the order. The other parts of it are more interesting.

First, KK’s analysis on the TRO is cursory: just one paragraph stating that the government probably has violated Richman’s Fourth Amendment rights by searching his data without a warrant.

The Court concludes that Petitioner Richman is likely to succeed on the merits of his claim that the Government has violated his Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures by retaining a complete copy of all files on his personal computer (an “image” of the computer) and searching that image without a warrant. See United States v. Comey, No. 1:25-CR272-MSN-WEF, 2025 WL 3202693, at *4–7 (E.D. Va. Nov. 17, 2025). The Court further concludes that Petitioner Richman is also likely to succeed in showing that, because of those violations, he is entitled to the return of the image under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g).

That’s on the third page of the four-page memo.

Before she gets there (and in addition to formally finding that DOJ has notice of Richman’s request), she focuses on the way DOJ is playing dumb. She notes she has spoken to unnamed people from DC USAO, who were helpful on administrative matters, thank you very much.

First, although the Court has been in communication with attorneys from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, 1 the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia has not yet entered an appearance to make representations on behalf of the Government, and counsel for the Government has not yet been identified. See Pet’r’s Ex. A, Dkt. No. 9-2.

1 These attorneys have helpfully facilitated communication on administrative matters. The Court appreciates counsel’s prompt assistance on these matters.

But no one, including Jocelyn Ballantine, wants to put their name on this docket.

And that’s a problem, Judge KK notes, because until someone files notice of appearance, there’s no formal way to start figuring out who has the data.

Second, the Government has not yet indicated who has custody of the material at issue, and neither the Petitioner nor the Court can determine the identity of the custodian until the Government appears in this case. Given that the custody and control of this material is the central issue in this matter, uncertainty about its whereabouts weighs in favor of acting promptly to preserve the status quo.

Maybe it’s something those helpful DC USAO personnel told her. Maybe it’s the way Ballantine deftly shared Richman’s motion with the Loaner AUSAs at EDVA, but not the DOJ leadership with whom Pirro had consulted by late day Thursday.

It’s like Colleen Kollar-Kotelly suspects DOJ is hiding the ball, and that’s why she ordered Richman to go right to the top with his request, to ensure Pam Bondi can’t pretend she’s ignorant of his request.

The perma-sealed Bill Barr dockets

There’s something else sketchy going on here.

As I noted, Richman attached the warrants used to seize his stuff. They’re still sealed and Judge KK has provisionally permitted them to remain that way.

But why are they still sealed?

Back on November 5, Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick ordered the Loaner AUSAs to get them unsealed or, if not, then to file a motion justifying the seal in DC.

ORDERED that the Government shall, on or before November 10, 2025, move in the issuing district to unseal the four 2019 and 2020 search warrants referenced in the Government’s Reply to Defendant’s Response to the Government’s Motion for Implementation of Filter Protocol (ECF 132), together with all attendant documents, or, in the alternative, file a motion in the issuing district setting forth good cause as to why the subject search warrants and all attendant documents should remain under seal, in whole or in part;

In that same order, he ordered that there’d be a discussion about unsealing all the references to the warrants in the Comey docket on November 21, which was before Judge Currie dismissed the indictment on November 24. The government was also going to have to defend keeping the filing explaining the notice given to Comey — and submitted as an exhibit to his first response to the effort to get a taint team — sealed that same day.

ORDERED that, if necessary, the Court shall hold a hearing on the pending motions to seal (ECFs 56, 72, 109, and 133) on November 21, 2025, at 10:00 a.m. in Courtroom 500, and the materials subject to those motions shall remain UNDER SEAL until further order of the Court; and it is further ORDERED that, to the extent the Government seeks to seal Exhibit A to Defendant’s Response to the Government’s Motion for Expedited Ruling (ECF No. 55-1), the Government shall file a supporting brief in accordance with Local Criminal Rule 49 on or before November 12, 2025; Defendant may file a response on or before November 19, 2025; and, if necessary, the Court shall hold a hearing on the Government’s sealing request on November 21, 2025, at 10:00 a.m. in Courtroom 500;

Best as I can tell, that never happened. For example, there are no gaps in the Comey docket hiding a sealed discussion about these sealed warrants.

And that’s interesting because when Fitzpatrick asked about all this back on November 5 — this is the hearing that led to the order to unseal the warrants — Rebekah Donaleski revealed that they asked Loaner AUSA Tyler Lemons about the warrants twice at that point, but had gotten no response.

Before we begin, what I’d like to do is — before we address the underlying issues, the government’s motion for a filter protocol, the defendant’s position, we have four outstanding sealing motions, and I do think those sealing motions will touch, at least in some way, on this motion; if not, motions that you-all are going to argue in the future. So what I’d like to do is see if we can nail down what the parties’ positions are and see if we can kind of resolve some of those sealing issues now, if possible.

As I understand it, there are four sealing motions that are outstanding. The defense has filed three; the government has filed one. All these sealing motions deal with either warrants that were issued in a sister district or one document that the government has provided to the defense in discovery.

MS. DONALESKI: Thank you, Your Honor. With respect to the one document provided in discovery, that’s our position, we have no objection. With respect to the underlying warrants which we attached to our motions, my understanding from Mr. Lemons is that he has moved to unseal those. We don’t know where — he hasn’t moved to unseal them — when. We’ve asked him twice for that information, and he hasn’t provided it. The defense’s view is that we should be entitled to proposed reasonable redactions for PII of those warrant affidavits and warrant materials. We have asked for an opportunity to do that and have not heard from the government. So our position is, the information in our motions, in the motion papers themselves, we have no objection to that being under seal — to that being publicly filed; but with respect to the warrants, which my understanding is those remain under seal by the District of D.C. court, we would ask that we be permitted an opportunity to propose redactions with the government.

[snip]

But with respect to the information that we’ve described in our motion papers, specifically referring to the offenses at issue in the Artic Haze warrants, the dates that the warrants authorize to search, the defense believes that those should be discussed publicly and those can be discussed publicly.

THE COURT: What about the affidavits in support of the warrants?

MS. DONALESKI: Those remain under seal. I don’t expect that we’ll need to get into what is in those affidavits in this hearing today, but if the government or the Court feels differently, we’d welcome that discussion.

And when Fitzpatrick asked Lemons about the warrants, the Loaner AUSA got a bit squirmy. Lemons had asked the AUSA to unseal the warrants. He had not filed a motion to unseal them, as if someone — maybe the AUSA in question, who may be Jocelyn Ballantine — advised him that was not a good idea.

THE COURT: Mr. Lemons, what’s the status of that?

MR. LEMONS: Thank you, Your Honor. Your Honor, we have made a request to the issuing district as to those search warrants, for them to be unsealed. My understanding, last speaking with an AUSA in that district, is that motion has not been filed at this time. They are preparing to provide notice to other potentially interested parties, per their practice and the rules they have to abide by in that district. So we requested it, and our understanding is at this time that the warrants all remain completely under seal. That is the only reason why the government designated these search warrants as protected material and filed them under seal and understands why the defense filed them under seal. If it was in my power and ability here today, those search warrants would be totally unsealed. [my emphasis]

“Preparing to provide notice to other potentially interested parties”? Who else would need notice? Richman and Comey were the ones suspected of leaking!

It has been a month but these dockets remain sealed.

One possible explanation for that is that the Loaner AUSAs (or perhaps Ballantine) filed a motion in DC on November 10 that is under seal, one that should not be sealed for Judge KK. So perhaps everyone is trying to hide the fact that after being ordered by Fitzpatrick not to access this data, Kash Patel just dealt it to someone else (possibly Jason Reding Quiñones). That might explain why Judge KK ordered the government they can only contest her order after giving “contemporaneous notice to counsel for Petitioner Richman:” because (hypothetically), having been ordered by MJ Fitzpatrick to stay out of Richman’s data, they instead dove deeper into it without telling him.

Or maybe the squirminess is about hiding how the underlying warrants were managed … by Jocelyn Ballantine.

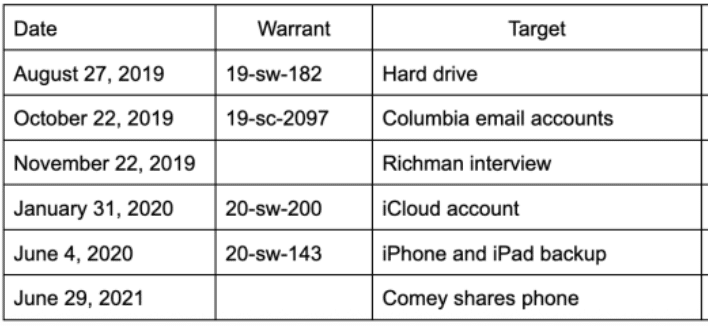

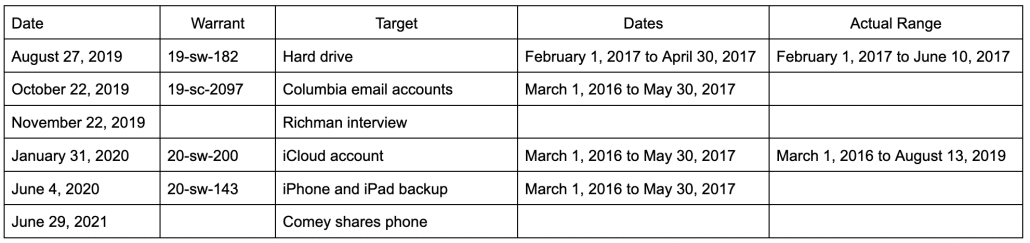

Revealing those warrants, after all, should not thwart the effort to keep snuffling about Richman’s data, except insofar as it would raise questions not directly addressed in Judge KK’s order. Just as one example, even though Richman in his initial motion and TRO request relied heavily on Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick’s opinion effectively describing rampant Fourth Amendment violations, he does not mention that when the FBI seized his iCloud account in 2020, they took content through August 13, 2019, more than two years after the date of the warrant (basically, through the date of the Comey Memo IG Report release).

According to an April 29, 2020 letter from Mr. Richman’s then-attorney to the government–produced to the Court ex parte by the defense–the Department of Justice informed Mr. Richman that the data it obtained from his iCloud account extended to August 13, 2019, well outside the scope of the warrant and well past the date on which Mr. Richman was retained as Mr. Comey’s attorney. ECF 181-6 at 20. The same letter further states that the Department of Justice informed Mr. Richman that it had seized data from Mr. Richman’s hard drive that extended to June 10, 2017–again well into the period during which Mr. Richman represented Mr. Comey–despite the warrant (19-sw-182) imposing a temporal limit of April 30, 2017. Id.

Did Ballantine — in whom Pirro has invested the trust to limit the blowback of the pipe bomb prosecution — allow the FBI to obtain data outside the scope of a warrant? Are there secret John Durham warrants someone is hiding?

It’s not clear who all this squirminess is designed to protect. But I feel like, whether or not Judge KK’s order halts DOJ efforts to dive into this unlawfully collected data, it may lead to some interesting disclosures about why everyone is so squirmy.

Update: Right wing propagandist (and daughter of a former whack job FBI agent) Mary Margaret Olohan gives the game away. One of her DOJ sources says this won’t be a setback … which sort of confirms that DOJ intends to continue to violate Richman’s Fourth Amendment.