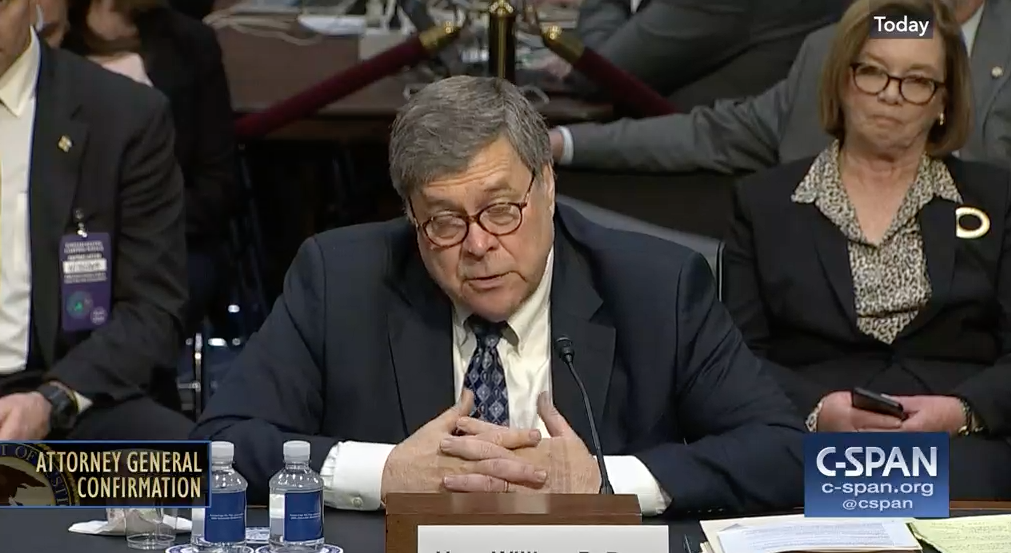

Billy Barr Signs a Memo That Wouldn’t Have Helped Carter Page

For eight months, FBI and DOJ have been diligently making changes to the way they do FISA applications, with regular reports into the FISA Court. Whether or not those changes are adequate to fix the problems that beset the Carter Page application, they represent significant effort.

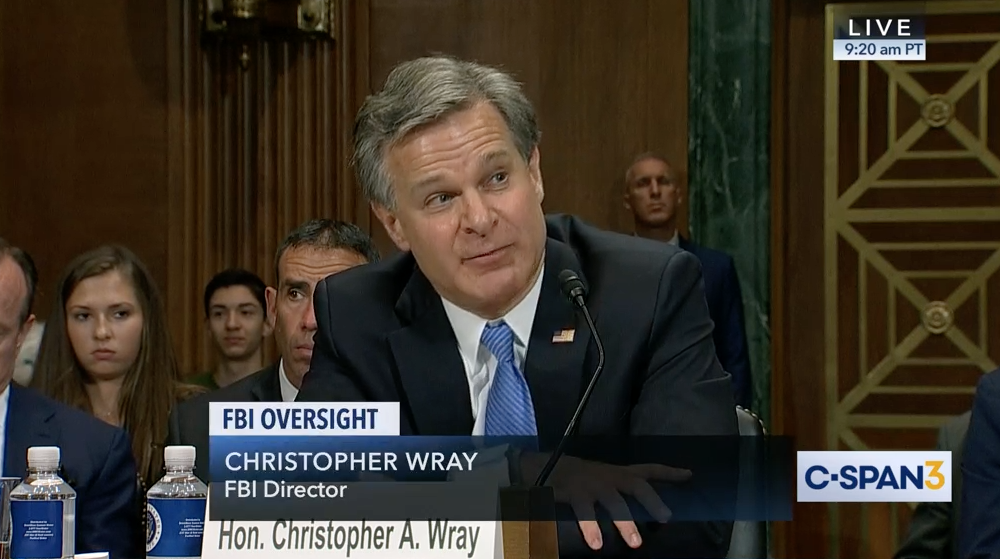

Curiously, a memo Billy Barr just released purporting to enhance compliance in FISA applications appears unaware of the filings at FISC, and instead cites only changes implemented in Christopher Wray’s response to the December 9, 2019 DOJ IG Report (see PDF 466 for his letter).

Therefore, in order to address concerns identified in the report by the Inspector General of the Department of Justice entitled, “Review of Four FISA Applications and Other Aspects of the FBI ‘s Crossfire Hurricane Investigation” (December 2019), and to build on the important reforms described by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) in his December 6, 2019, response to the Inspector General’s report, I hereby direct that the following additional steps be taken:

Arguably (as I’ll show), at least one of the provisions in the memo is weaker than a change FISC mandated itself.

And while the memo claims to want to protect the rights of people like Carter Page, Barr’s memo would in no way apply to Page. That’s because the special protections tied to political campaigns only apply to those currently associated with campaigns.

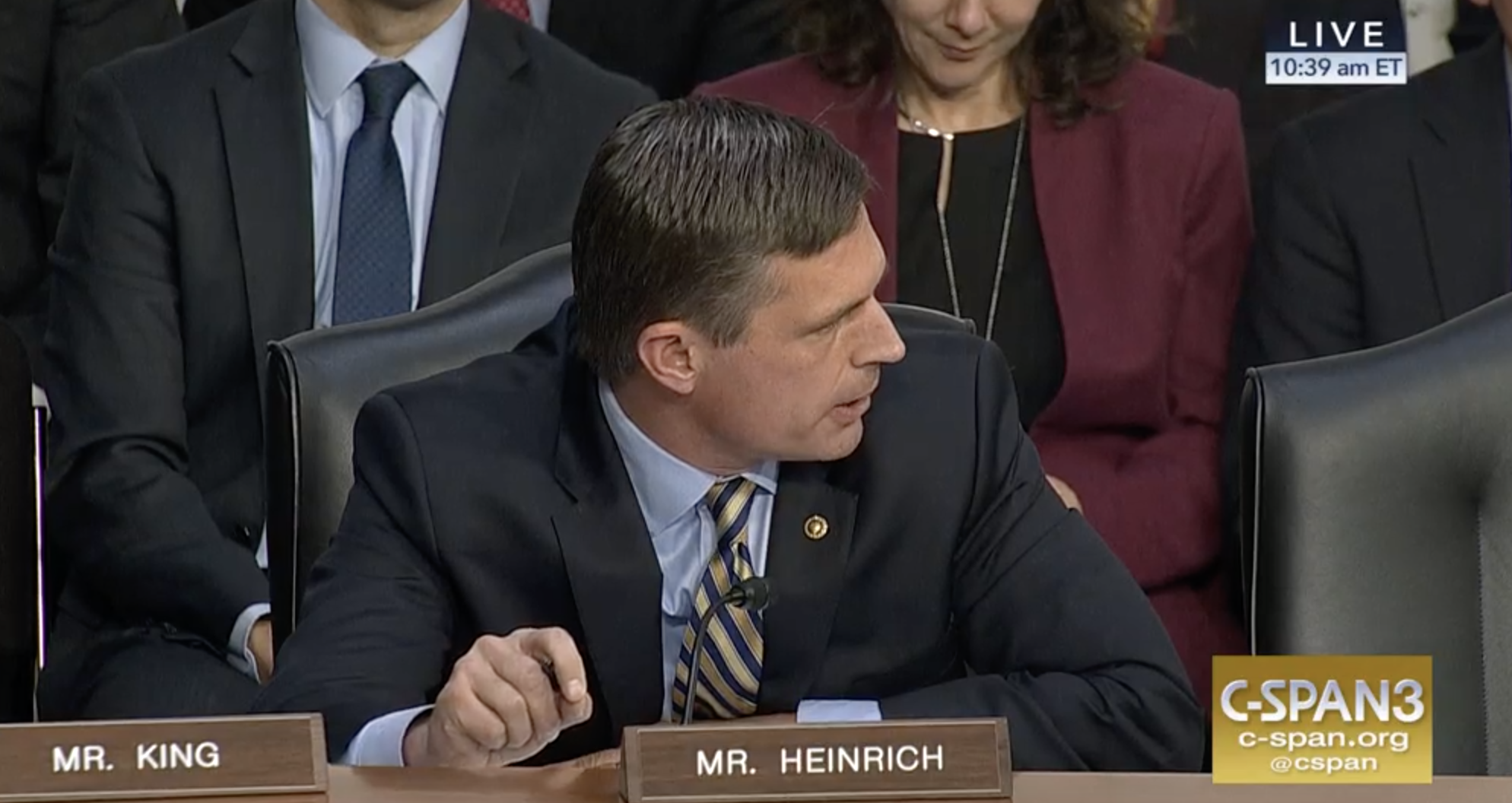

With respect to applications for authorization to conduct electronic surveillance or physical searches pursuant to FISA targeting (i) a federal elected official or staff members of the elected official, or (ii) an individual who is a declared candidate for federal elected office or staff members or advisors of such candidate’s campaign (including any person who has been publicly announced by a campaign as a staff member or member of an official campaign advisory committee or group, or any person who is an informal advisor to the campaign),

By the time FBI applied for a FISA application targeting Page, several prominent members of the campaign had dissociated the campaign from him — for his controversial ties to Russia! — in no uncertain terms; those disavowals were included in the FISA application. Yes, Page had been announced as an informal advisor, but then the campaign made very clear he was no longer an informal advisor (and even claimed he never had been).

To be sure, some of the changes proposed — both those limited to those connected with a campaign and the more general ones — are improvements. For example:

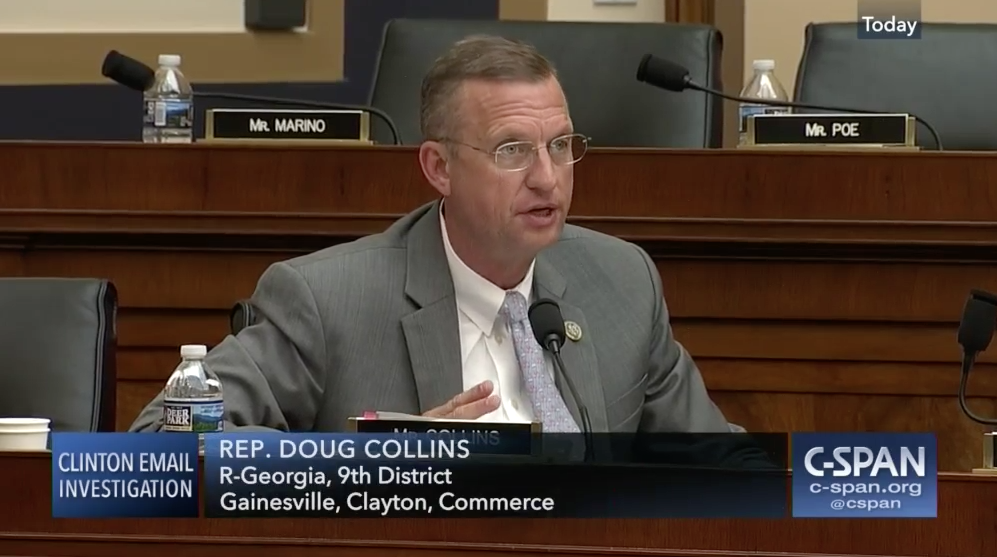

- ¶3(b) requires non-delegable sign-off by the Director of the FBI and the Attorney General) of any application targeting someone associated with a campaign; while requiring non-delegable sign-off may introduce some problems, this is the kind of certification recommended by the DOJ IG Report (though arguably is already incorporated in the December 6, 2019 letter Barr cited).

- ¶3(d) and ¶3(e) institutes a shorter renewal deadline for these political FISAs, 60 days instead of 90, and requires monthly reports to FISC describing the results and affirming the continued need for such surveillance. These are arbitrary but perhaps useful improvements, not least because by increasing the paperwork required to surveil a political target, they make it more likely that such surveillance will actually be worth it (as the third and fourth applications targeting Page were not).

- ¶3(f) requires that any political application describe whether less intrusive investigative procedures have been considered — something already required in all FISA applications — and an explanation why those procedures weren’t used. Such a requirement would have been useful in Page’s case (as I noted last year), because it would have emphasized the efforts FBI was making not to take public actions, but in practice this response would almost always point to DOJ guidelines on avoiding taking public actions that might affect an election and might actually encourage the increased reliance on informants, something Trump’s people claim equates to FISA surveillance. A requirement like this might be useful if it took place in the scope of a debate about what techniques were intrusive or not, but there’s zero evidence such a debate has happened.

The memo has two parts on defensive briefings, probably designed to placate Republicans, but which likely don’t do much in practice:

- For political targets, ¶3(a) requires the FBI Director to consider a defensive briefing before targeting someone, and if no briefing is given, then the Director must document it in writing. FBI did consider defensive briefings for Trump’s people, but for various reasons decided not to do it, but in the case of Carter Page, he had long been wittingly sharing non-public information with known Russian intelligence officers and when FBI tried to explain why such dalliances were problematic in March 2017, he simply disagreed. A defensive briefing for Page would have been as useless as President Obama’s warnings to Trump that Mike Flynn was a problem.

- For all counterintelligence concerns pertaining to election interference, ¶4 requires the FBI Director to “promulgate procedures, in consultation with the Deputy Attorney General, concerning defensive briefings.” Not only is this requirement utterly silent about what such procedures should do, not only did Wray commit to a similar recommendation in his December 2019 letter, but defensive briefings are precisely what Acting Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe is currently politicizing.

As for key review processes mandated by the memo, some are just redundant at best or stupid at worst. For example:

- ¶1 requires FBI personnel to review the accuracy sub-file before submitting a FISA application. That process is already in place. It’s called the Woods Procedure and it’s the procedure that failed to find errors in the Page application.

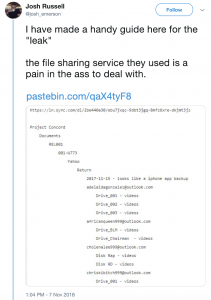

- ¶2 requires someone — it doesn’t say whether FBI or NSD bears responsibility — to report any misstatement or omission to FISC. That’s already required. Plus, this requirement twice gives NSD the authority to determine whether something amounts to a reportable incident. The ongoing DOJ IG investigation into all the errors in FISA applications suggest NSD has deemed some omissions and errors not to be worthwhile of reporting (indeed, there were multiple instances in the Page applications where NSD did not include information they knew of, in at least one case information that FBI did not have). In short, this paragraph seems more focused on ensuring NSD — and not an outside entity, like DOJ IG or the FISC — retains the ability to determine what is and is not a reportable error.

- ¶3(c) requires an FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge who is not involved in an investigation to review the FISA application of any defined political targets. The DOJ IG Report found that even NSD lawyers involved in an investigation don’t have enough insight into a case to identify omissions. While an ASAC might have access to case files that NSD lawyers do not, there’s zero reason to believe someone with even less insight into an investigation would better be able to spot omissions than an NSD lawyer with an ongoing role in the application. So this review is likely useless busywork.

- ¶3(g) requires the Assistant Attorney General to review the case file of a political target within 60 days of its initial grant to make sure everything is kosher, including that the investigation was properly predicated. In conjunction with the shorter renewal timeframe of such applications (which would require DAG sign-off in any case), all this amounts to is a heightened review on first renewal (the memo does not say this is not delegable, so such a review will and probably should not be done by the AAG). But in Page’s case, it would have done nothing (indeed, at the time this would have been done for Page, he was in Russia meeting high level officials, falsely claiming to represent Trump’s interests).

In short, while some of these changes are salutary, a number are just show, and some are worthless busy work.

But my real concern about them — particularly given how Barr only invokes the first Christopher Wray letter to DOJ IG — is how they interact with other details of the FISA reform events that have transpired since last December.

For example, in the last month, the FBI and DOJ engaged in a big dog-and-pony show to claim that none of the errors DOJ IG had identified in 29 FISA applications they reviewed affected probable cause and just two were material. Effectively, that big press push amounted to having NSD pre-empt DOJ IG’s findings in an ongoing investigation, and the public details of NSD’s own review raise abundant reason to doubt the rigor of it. So Barr’s emphasis (in ¶2) on NSD’s role in deciding what is an error seems to be a reassertion of the status quo ante in the midst of an ongoing investigation that is still assessing whether NSD’s reviews are adequate. That makes this feel like another attempt to pre-empt an ongoing investigation.

Even more troubling, Barr’s memo seems unaware of — and in key respects, conflicts with — an order presiding FISA Judge James Boasberg issued in March. As I noted at the time, that order recognized something that was apparent from the DOJ IG Report but which the IG either missed, ignored, or was bureaucratically unable to address: it wasn’t just FBI that dropped the ball on the Page FISA application, NSD did so too.

According to the OIG Report, the DOJ attorney responsible for preparing the Page applications was aware that Page claimed to have had some type of reporting relationship with another government agency. See OIG Rpt. at 157. The DOJ attorney did not, however, follow up to confirm the nature of that relationship after the FBI case agent declared it “outside scope.” Id. at 157, 159. The DOJ attorney also received documents that contained materially adverse information, which DOJ advises should have been included in the application. Id. at 169-170. Greater diligence by the DOJ attorney in reviewing and probing the information provided by the FBI would likely have avoided those material omissions.

Because of that, Boasberg required that DOJ attorneys, too, sign off on all FISA applications, and suggested they get more involved earlier in the process.

As a result, reminders of DOJ’s obligation to meet the heightened duty of candor to the FISC appear warranted. The Court is therefore directing that any attorney submitting a FISA application make the following representation: “To the best of my knowledge, this application fairly reflects all information that might reasonably call into question the accuracy of the information or the reasonableness of any FBI assessments in the application, or otherwise raise doubts about the requested probable cause findings.”

DOJ should also consider whether its attorneys need more formalized guidance – e.g. , their own due-diligence checklists. Consideration should also be given to the potential benefits of DOJ attorney visits to field offices to meet with case agents and review investigative files themselves, at least in select cases – e.g. , initial applications for U.S.-person targets. Increased interaction between DOJ attorneys and FBI case agents during the preparatory process should not only improve accuracy in individual cases but also likely foster a common understanding of how to satisfy the government’s heightened duty of candor to the FISC.

There’s no mention of Boasberg’s order and suggestions in Barr’s memo, and it’s unclear whether that’s because he has no idea what has transpired with the FISC, whether he thinks he can ignore Boasberg’s order, or whether his memo is just for show. In any case, it’s notable that Barr’s memo doesn’t incorporate the key insight Boasberg made, that FISA requires increased diligence from NSD, too.

Similarly, because Boasberg deemed the role of FBI’s lawyers to be “perfunctory,” he asked for more details about their role.

But the role described in the revised Woods Form appears largely 10 perfunctory. To assess whether additional modifications to the Woods Form or related procedures may be warranted, the Court is directing the FBI to describe the current responsibilities FBI OGC lawyers have throughout the FISA process.

Here, Barr has added one more FBI person (an ASAC uninvolved in the case) to the process, whose review can only be perfunctory, rather than ensuring that those with more visibility on the process have a substantive role. Barr also doesn’t incorporate into his memo a change that came from Amicus David Kris after the Wray letter cited in Barr’s memo that case agents attest to the accuracy of FISA reviews, a recommendation FBI adopted, which might accomplish more than any review by an outside ASAC.

There’s one more reason this memo is concerning. ABC reported the other day that long-time Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Legal Policy Brad Wiegmann was reassigned two weeks ago and replaced by a far less experienced political appointee, Kellen Dwyer (though I’ve seen people vouch for his integrity — he’s not a hack). Wiegmann would likely be part of discussions about how to meet FISC’s demands for further accountability.

Though a relatively small unit of fewer than two dozen attorneys, the Office of Law and Policy participates in almost every National Security Council meeting, works with congressional staff to draft new legislation, and conducts oversight of the FBI’s intelligence-gathering activities.

“[It] has been sort of the center of gravity for the Department of Justice on national security policy, and it’s a central role,” said Olsen, who at one point ran the department’s National Security Division and later advised Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

Wiegmann has led the office since the Obama administration and for almost all of the Trump administration.

In particular, Wiegmann has long been involved in efforts to meet FISC’s demands regarding surveillance it authorizes. Here, just days after Wiegmann’s removal, Barr is issuing a memo that seems unaware of and in at least a few respects, potentially inconsistent with, explicit orders from the presiding FISA Judge.

There’s nothing obviously offensive about this memo. But it would do little to prevent a repeat of the Carter Page problems. And it’s not clear that it adds anything to the very real efforts to improve the FISA process at DOJ. Indeed, it may well be an effort to pre-empt more substantive concerns about the role of NSD (as opposed to FBI) in this process.

Barr released a second memo creating an audit mechanism for national security functions that feels like an effort to get ahead of ongoing DOJ IG investigation. I welcome additional oversight of FBI’s national security functions, though the timing of this and the timing of its implementation — with a report on its creation due just days before the election but all review of its functionality years down the road — feels like an attempt to stave off real legal oversight.