Scene-Setter for the Sussmann Trial, Part One: The Elements of the Offense

Thanks to those who’ve donated to help defray the costs of trial transcripts. Your generosity has funded the expected costs. If you appreciate the kind of coverage no one else is offering, we’re still happy to accept donations for this coverage — which reflects the culmination of eight months work.

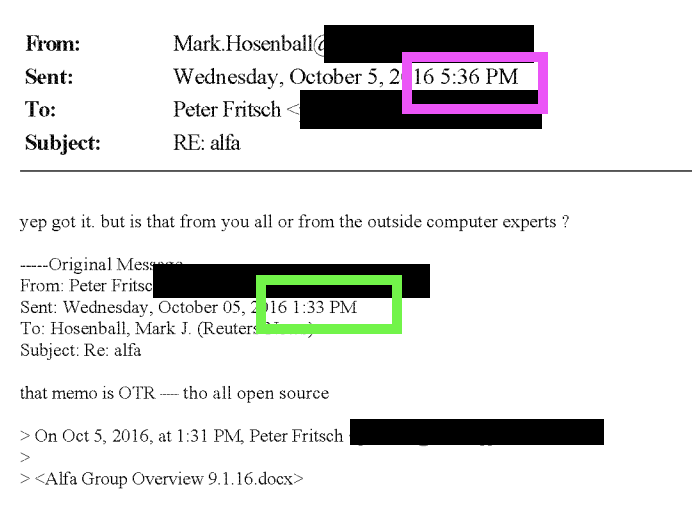

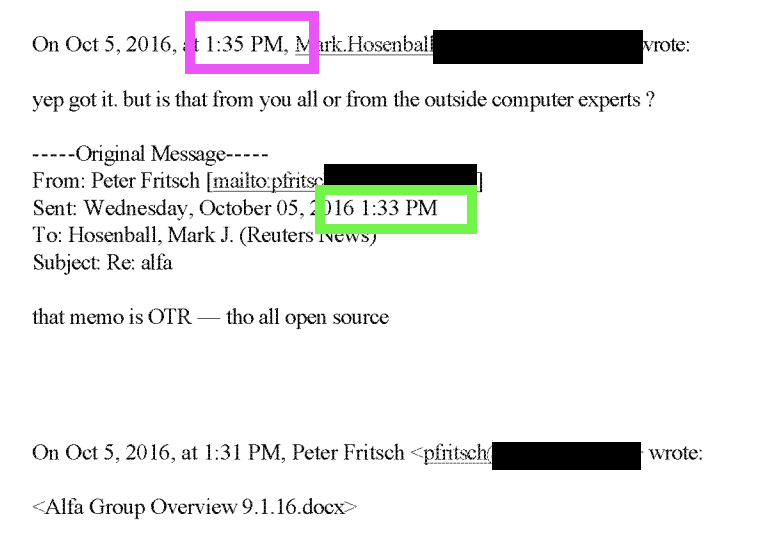

In the first of what will be a number of “scene-setters” for the Michael Sussmann trial next week, Devlin Barrett makes two significant errors. First, he misrepresents what Sussmann said in a text to James Baker on September 18, 2016.

In a text message setting up the meeting, Sussmann claimed he was not representing any particular client in bringing the matter to the FBI’s attention.

Here’s what the text says:

Jim – it’s Michael Sussmann. I have something time-sensitive (and sensitive) I need to discuss. Do you have availibilty [sic] for a short meeting tomorrow? I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau. Thanks.

[I’m unclear whether the misspelling of “availability” is Sussmann’s or Durham’s.]

The distinction between “representing” and “on behalf of” will be a core issue litigated in this trial (as I’ll lay out below), which makes Barrett’s sloppiness affirmatively misleading.

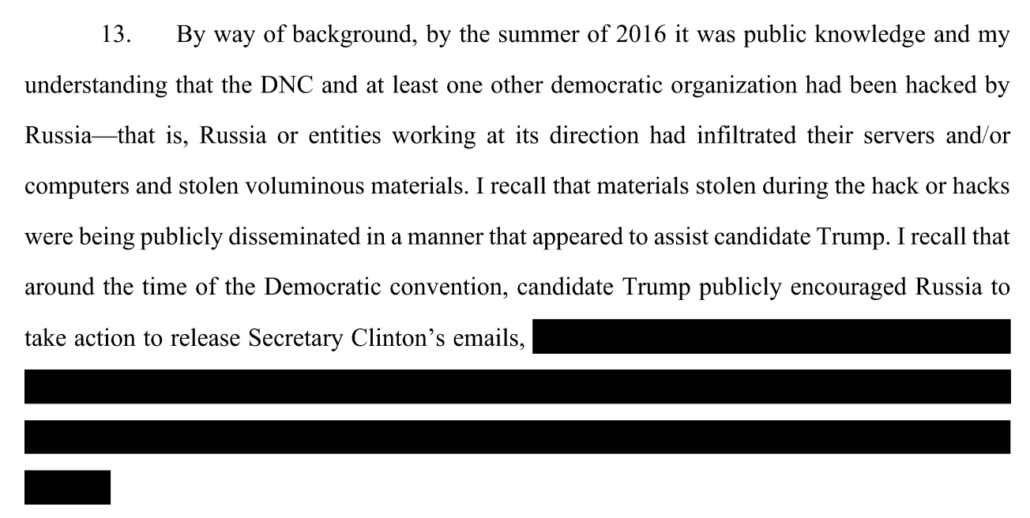

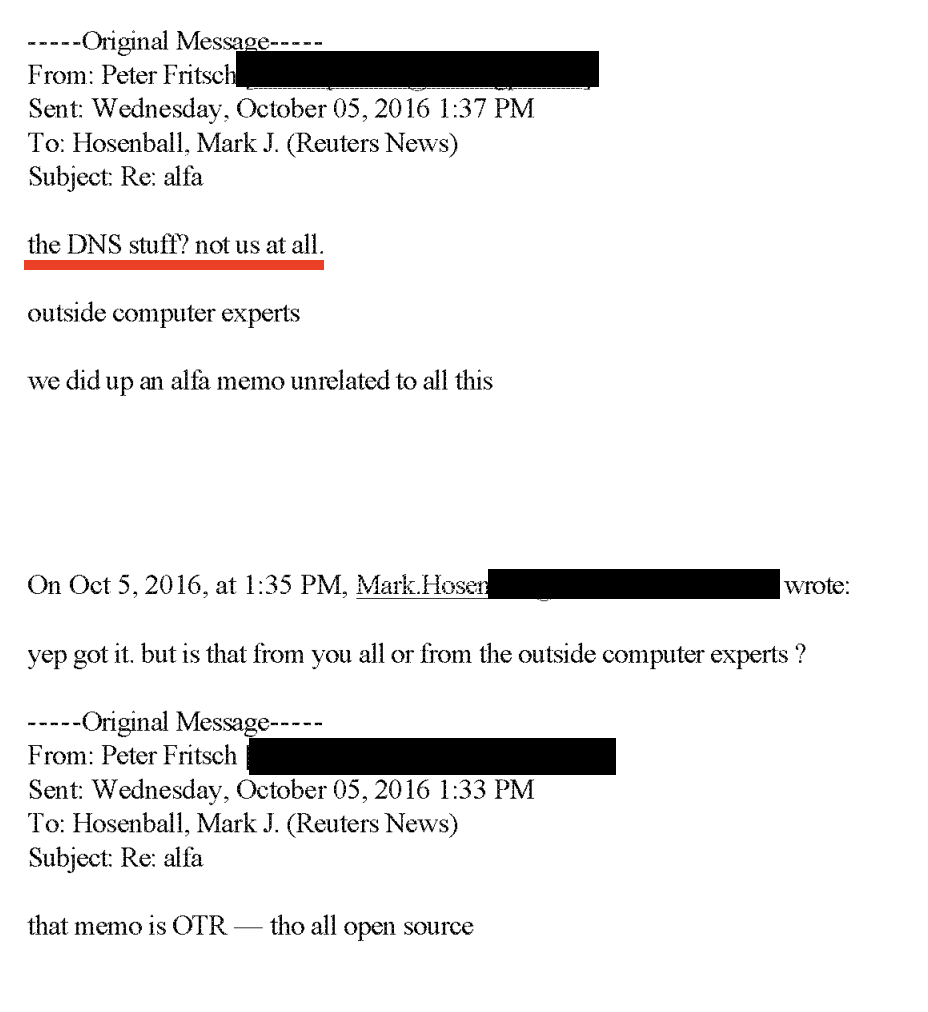

Second, Barrett serially accepts Durham’s framing — that the cybersecurity researchers who started identifying the Alfa Bank anomaly months before Rodney Joffe ever talked to Michael Sussmann were doing “campaign research.”

The two-week trial will delve into the murky world of campaign research, lawyers and the role the FBI played in that election, as Trump and Hillary Clinton vied for the presidency, and federal agents pursued very different investigations surrounding each of them.

[snip]

Prosecutors signaled this week that they plan to call a host of current and former law enforcement officials to describe how the FBI pursued the Alfa Bank accusations, and to paint Sussmann as part of a “joint venture” that included Joffe, Clinton’s campaign, research firm Fusion GPS and cybersecurity experts.

[snip]

Cooper, however, has limited how deeply Durham’s team may go into the particulars of any alleged joint venture among Democratic operatives, ruling that he will not allow “a time-consuming and largely unnecessary mini-trial to determine the existence and scope of an uncharged conspiracy to develop and disseminate the Alfa Bank data.”

Barrett does this in spite of the fact that Durham has repeatedly said the only evidence he has supporting his joint venture conspiracy theory (even assuming it were illegal) is billing records. While Barrett cites the gist of Cooper’s ruling excluding Durham’s unsubstantiated claims of a “joint venture,” he doesn’t quote Cooper noting that, “some evidence suggests that Fusion GPS employees had no connection to the gathering or compilation of the Alfa Bank data.” Effectively, an experienced DOJ reporter has fallen for Durham’s use of unsubstantiated materiality claims to frame a prosecution that didn’t charge the underlying conspiracy. That’s a real disservice to readers who don’t know the difference between uncharged materiality claims and a charged conspiracy.

So here’s my effort to explain to newbies what the trial is about. Durham has to prove that:

- Michael Sussmann said what Durham claims Sussmann did to James Baker on September 19, 2016

- What he said was a lie

- The alleged lie was material to the functioning of the FBI

Durham has to prove that Sussmann said what Durham claims he did on September 19, 2016

From the start, Durham has been uncertain what lie Sussmann told. As Sussmann pointed out in a motion for a bill of particulars right from the get-go, at various points in the indictment, Durham claimed that Sussmann’s lie was:

- “that he was not doing his work on the aforementioned allegations ‘for any client'” (one)

- “that he was not acting on behalf of any client” (one, two)

- that he was not “acting on behalf of any client conveying particular allegations concerning a Presidential candidate” (one)

That is, repeatedly in the indictment, Durham was conflating the “work” of chasing down the allegations (which is not at issue in this prosecution at all) with the meeting where Sussmann shared those allegations with the FBI. The last formulation is what Durham charged, but as we’ll see, unless Durham supersedes this indictment today, he may have problems with that formulation as well.

Almost six months after Durham charged Sussmann for lying about sharing allegations on September 19, he got rock-solid proof — a text from Sussmann to Baker that Durham only found because Sussmann kept asking Durham to go back and look for these records — that Sussmann said, he was “coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau,” on September 18.

That rock-solid proof actually presents two problems for Durham. First, it raises the possibility that, even if the jury decides this was a lie, Durham can only prove Sussmann said it on September 18, not September 19. But the text also suggests what Sussmann may have meant by “on behalf of:” who benefits. He was not seeking a benefit for a client, he was trying to benefit the FBI.

That interpretation is consistent with what Sussmann said under oath in 2017, and it is an interpretation that Durham did not test before he charged Sussmann.

I was sharing information, and I remember telling him at the outset that I was meeting with him specifically, because any information involving a political candidate, but particularly information of this sort involving potential relationship or activity with a foreign government was highly volatile and controversial. And I thought and I remember telling him that it would be a not-so-nice thing ~ I probably used a word more stronger than “not so nice” – to dump some information like this on a case agent and create some sort of a problem. And I was coming to him mostly because I wanted him to be able to decide whether or not to act or not to act, or to share or not to share, with information I was bringing him to insulate or protect the Bureau or — I don’t know. just thought he would know best what to do or not to do, including nothing at the time.

And if I could just go on, I know for my time as a prosecutor at the Department of Justice, there are guidelines about when you act on things and when close to an election you wait sort of until after the election. And I didn’t know what the appropriate thing was, but I didn’t want to put the Bureau or him in an uncomfortable situation by, as I said, going to a case agent or sort of dumping it in the wrong place. So I met with him briefly and

[snip]

so I told him this information, but didn’t want any follow-up, didn’t ~ in other words, I wasn’t looking for the FBI to do anything. I had no ask. I had no requests. And I remember saying, I’m not you don’t need to follow up with me. I just feel like I have left this in the right hands, and he said, yes. [my emphasis]

As has been explained over and over, Jim Baker’s testimony about what Sussmann said to him on September 19 (as opposed to what Sussmann texted him on September 18) has been all over the map:

- An October 3, 2018 Baker interview Baker said he didn’t recall Sussmann saying he was there on behalf of Hillary.

- An October 18, 2018 Baker interview Baker said that in that first meeting, he did not recall Sussmann saying he was acting on behalf of a specific client.

- A July 15, 2019 Baker interview Baker said Sussmann was sharing information from cybersecurity experts.

- A June 2020 Durham interview Baker said it did not seem like Sussmann was representing a client (and he was not aware that Sussmann represented the DNC.

- Three more Durham interviews with Baker on this subject that align with the indictment.

Durham will argue that he got Baker’s testimony to match what he, Durham, claims to be sure is the truth by refreshing his memory with notes that Bill Priestap and Trisha Anderson took, the former when Baker told him about the meeting immediately afterwards and the latter in circumstances that are less clear.

The Priestap notes say four things:

- Represent DNC, Clinton Foundation etc

- Been approached by prominent cyber people

- NYT, Wash Post, or WSJ on Friday

- [Written slantways for reasons Priestap could not explain] said not doing this for any client

The Anderson notes say two things:

- No specific client but group of cyber academics talked with him about research

- Article this Friday, NYT/WPost [the notes fade out]

None of those notes say “on behalf of,” Anderson’s don’t address whether Sussmann offered up the claim or not, and Priestap seems to have written “not doing this for any client” after the fact, as if it wasn’t part of Baker’s initial telling.

None of those notes make it clear what part of the information Baker passed on came from the meeting itself and what part came from the text he had received the day before (and indeed, Priestap’s slantways note may suggest the detail about a client could have come later). Durham only has a refreshed memory of what Baker knew by September 19, not which parts he learned on September 18 and which he learned on September 19.

Literally six months after indicting Sussmann, Durham gave him different sets of notes recording how Andy McCabe explained the allegations to Dana Boente on March 6, 2017.

One set, from Tashina Gauhar’s notes, says this:

“Attorney” Brought to FBI on behalf of his client

Also advised others in media > NYT

Another set, from Mary McCord’s notes, says this:

First brought to FBI att by atty

[snip]

Attorney brought to Jim Baker + d/n say who client was. Said computer researchers saw the [activity?]. Said media orgs had the info, including NY Times.

These notes admittedly reflect what the FBI came to understand, possibly in the September 19 meeting, possibly hours after the September 19 meeting, possibly days, possibly months. But as McCord recorded it, the emphasis remained on the computer researchers and the NYT. That emphasis is important for materiality questions.

Durham has to prove what Sussmann said was a lie

Next, Durham has to prove that what Sussmann said was an intentional lie.

Probably, Durham will use the formulation Sussmann sent in his September 18 text, “I’m coming on my own – not on behalf of a client or company – want to help the Bureau,” since that’s the only thing he has real proof of. This is why Sussmann tried to nail down Durham on what “on behalf of” shortly after being charged. Because it could mean, “on the orders of,” “for a client I am retained by,” or “seeking some benefit or ask for.”

But Sussmann’s explanation, “want to help the Bureau,” tied as it is to some benefit for the FBI, presents new problems for Durham. As noted above, that’s precisely what Sussmann said in sworn testimony back in 2017, when he had no reason to believe there would ever be a special prosecutor checking his claims and at a time he no longer had that text to check. Sussmann framed it in terms of giving the FBI maximal flexibility during campaign season.

Importantly, Sussmann did take steps to help the Bureau, by (with Joffe’s assent), helping the FBI kill the story the NYT was close to publishing. Which is another thing Sussmann described when he testified under oath in 2017 and another thing Durham didn’t bother to investigate before indicting.

I just wanted to tell you about a phone call that I had with him 2 days after I met with him, just because I had forgotten it When I met with him, I shared with him this information, and I told him that there was also a news organization that has or had the information. And he called me 2 days later on my mobile phone and asked me for the name of the journalist or publication, because the Bureau was going to ask the public — was going to ask the journalist or the publication to hold their story and not publish it, and said that like it was urgent and the request came from the top of the Bureau. So anyway, it was, you know, a 5-minute, if that, phone conversation just for that purpose.

Along with the September 18 text showing Sussmann told Baker he wanted to help the FBI, there were several texts reflecting that when Baker asked Sussmann for the name of the outlet that was reporting on the Alfa Bank allegations, Sussmann told Baker he had to ask someone before sharing the name.

Those text messages include, among other things, texts indicating that Mr. Sussmann asked to meet with Mr. Baker in September 2016 not on behalf of a client but to help the Bureau; texts indicating that Mr. Sussmann told Mr. Baker he had to check with someone (i.e., his client) before giving him the name of the newspaper that was about to publish an article regarding the links between Alfa Bank and the Trump Organization; and other texts, including a copy of a tweet that then-President Trump posted regarding Mr. Sussmann.

Then, Sussmann and Baker spoke on the phone several times on September 21 and 22.

Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Baker also had several phone conversations over the course of that week, including on Wednesday, September 21 and on Thursday, September 22.

We’ll learn more details at the trial, but we know that Baker and Bill Priestap called the NYT and got them to kill the story.

One reason this is important is because — as Sussmann’s attorney noted in a recent hearing — this is the opposite of what Sussmann would have done if he was working on behalf of the campaign.

We expect there to be testimony from the campaign that, while they were interested in an article on this coming out, going to the FBI is something that was inconsistent with what they would have wanted before there was any press. And in fact, going to the FBI killed the press story, which was inconsistent with what the campaign would have wanted.

The decision to go to the FBI contravened Hillary’s best interest.

The other reason those exchanges are important is because, as Sussmann pointed out, the best explanation for how Andy McCabe (that “top of the Bureau” that decided to take steps to kill the story) came to learn that Sussmann did have a client was via those exchanges.

The FBI could not have come to that belief based on conversations they had with Mr. Sussmann after his phone calls with Mr. Baker the week of September 19, 2016, because the FBI chose not to interview Mr. Sussmann about the information he provided to Mr. Baker, and the FBI chose not to ask Mr. Sussmann about or interview the cyber experts whom Mr. Sussmann identified as the source of the information he shared with the FBI.

Indeed, that timeline may explain why Baker’s memories about this are so inconsistent: because what Sussmann told him on September 18, what he told him on September 19, and what he told him on September 21 have all blended into one.

In any case, though, the best evidence suggests the FBI probably learned Sussmann had a client within three days of the time Sussmann first brought the allegations to the FBI (because that was the last he spoke with the FBI). That undermines Durham’s claim that Sussmann was hiding some big conspiracy. Within days, he appears to have made it obvious he did have a client.

Durham has to prove the alleged lie was material to the functioning of the FBI

I’m not going to get too far into the work Durham will have to do to prove that Sussmann’s lie — if he can prove what Sussmann said, if he can prove Sussmann said it on September 19 and not September 18, and if he can prove it really was a lie — had the ability to affect the decisions the FBI could have made.

Sussmann has many ways to attack Durham’s materiality argument. He’ll do so by proving:

- FBI knew he represented the Democrats (indeed, that’s what Priestap’s notes say)

- FBI knew of his ties to Joffe

- His characterization that this came from cybersecurity experts was true

- After the Franklin Foer piece was published, a separate FBI Agent attempted to open an investigation (showing what would have happened if Sussmann had not shared the information and just let NYT publish)

If I were him, I would also point to all the evidence (including from the March 2017 notes) that what most mattered to the FBI was not whom his client was but that the NYT was going to publish this.

But, given the timeline laid out by Sussmann’s texts and calls with James Baker, I’d make one more point. All the evidence suggests that FBI knew he had a client by September 22 — probably by September 21.

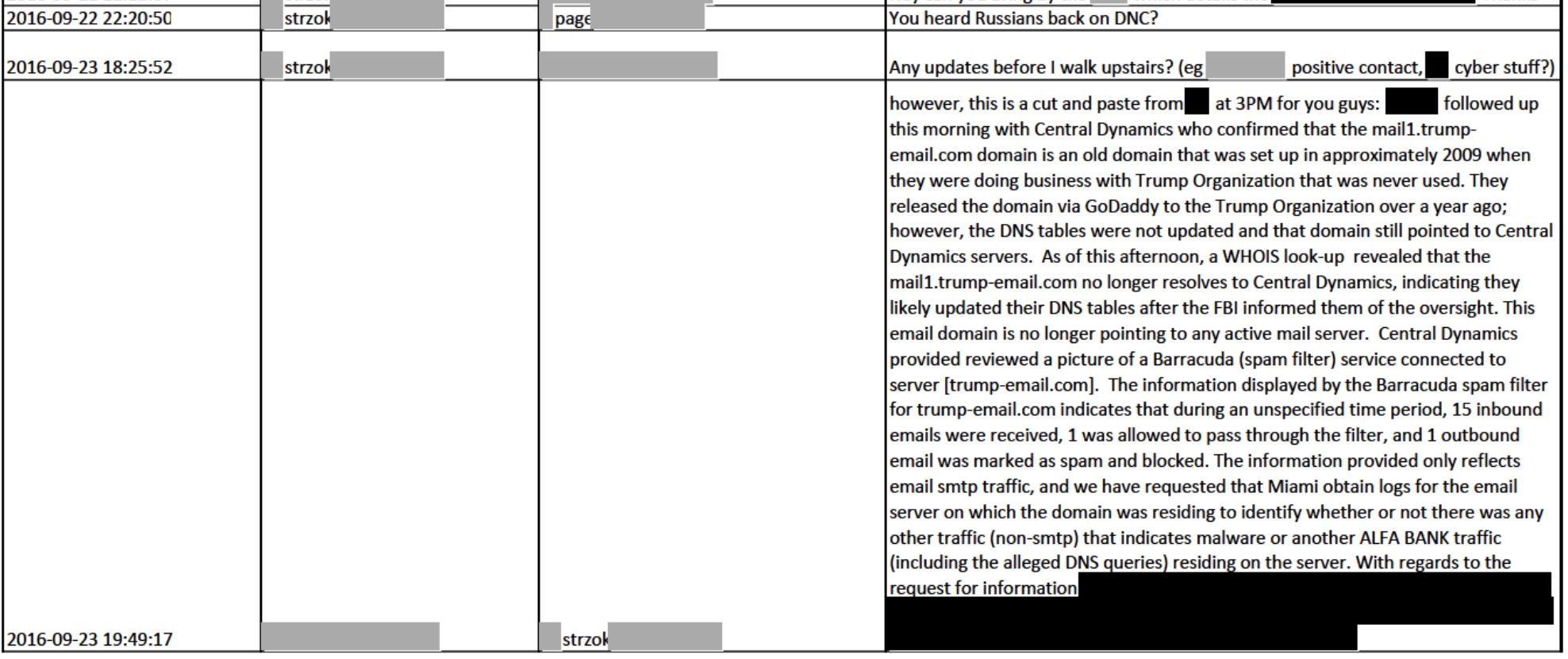

The FBI Agents who will describe the steps they took will apparently describe making a second call to Cendyn on September 23.

That is, the timeline will show that FBI learned Sussmann had a client before they even spoke to Cendyn a second time.

If Sussmann’s client or clients mattered, the FBI learned about them so early in the process that it would not have affected the overall investigation.

Durham’s tactical retreat

I know a lot of people think Durham has a slam-dunk case with that September 18 text, but that’s simply not the case — though as always, you never know what a jury is going to decide.

But I think that Durham is already planning a tactical retreat.

As Sussmann noted in a recent filing summarizing conflicting views on jury instructions, Durham’s indictment describes Sussmann’s alleged lie this way:

[O]n or about September 19, 2016, the defendant stated to the General Counsel of the FBI that he was not acting on behalf of any client in conveying particular allegations concerning a Presidential candidate, when in truth, and in fact, and as the defendant knew well, he was acting on behalf of specific clients, namely, Tech Executive-1 and the Clinton Campaign.

Never mind that Durham characterized the allegations as pertaining to “a Presidential candidate,” which presents other problems for Durham, he has also accused Sussmann of lying about having two clients.

Mr. Sussmann proposes modifying the last sentence as follows, as indicated by underlining: Specifically, the Indictment alleges that, on or about September 19, 2016, Mr. Sussmann, did willfully and knowingly make a materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statement or representation in a matter before the FBI, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2), namely, that Mr. Sussmann stated to the General Counsel of the FBI that he was not acting on behalf of any client in conveying particular allegations concerning Donald Trump, when, in fact, he was acting on behalf of specific clients, namely, Rodney Joffe and the Clinton Campaign.5 The government objects to the defense’s proposed modification since it will lead to confusion regarding charging in the conjunctive but only needing to prove in the disjunctive.

4 Authority: Indictment.

5 Authority: Indictment.

Durham’s language about “conjunctive” versus “disjunctive” will likely be the matter for heated debate next week. Particularly in the wake of Cooper’s decision that the materials from the researchers won’t come in as evidence, Durham seems to be preparing to prove only that Sussmann lied about representing Hillary, and not about Joffe. Sussmann, meanwhile, seems to believe that Durham will have to prove that his alleged lie was intended to hide both alleged clients.

The problem with Durham’s fall-back position is that if Sussmann really were representing Hillary at that FBI meeting, he wouldn’t have killed the NYT story that would have helped her campaign.

Update: Corrected date on Sussmann’s HPSCI interview, which was 2017.