Brittain Shaw’s Privileged Attempt to Misrepresent Eric Lichtblau’s Privilege

Thanks to those who’ve donated to help defray the costs of trial transcripts. Your generosity has funded the expected costs. If you appreciate the kind of coverage no one else is offering, we’re still happy to accept donations for this coverage — which reflects the culmination of eight months work.

In the first words of her opening argument in the Michael Sussmann case, Durham prosecutor Brittain Shaw argued that this case is all about Sussmann’s privilege, his purported ability to exploit high level ties at DOJ to seed what she claims would be a smear campaign against the guy who was, in fact, hiding secret communications with the Kremlin and soliciting hacks of his opponent.

The evidence will show that this is a case about privilege: the privilege of a well-connected D.C. lawyer with access to the highest levels of the FBI; the privilege of a lawyer who thought that he could lie to the FBI without consequences; the privilege of a lawyer who thought that for the powerful the normal rules didn’t apply, that he could use the FBI as a political tool.

The really painful irony of this case, though, is that Sussmann is being significantly hamstrung because of privilege, attorney-client privilege, because it is limiting his ability to present evidence about what really happened.

When Judge Christopher Cooper ruled that a subset of emails that had been protected under privilege were not, after all, he explained that, the documents, “do not strike the Court as being particularly revelatory.” Even so, Sussmann and Fusion can’t, ethically, simply offer up emails over which the Democrats are claiming privilege. There’s good reason to believe if they could, they could show that significant parts of Durham’s conspiracy theory have been based on imagining that Democrats were hiding the worst possible plotting behind privilege claims, when in fact the reality was much more mundane.

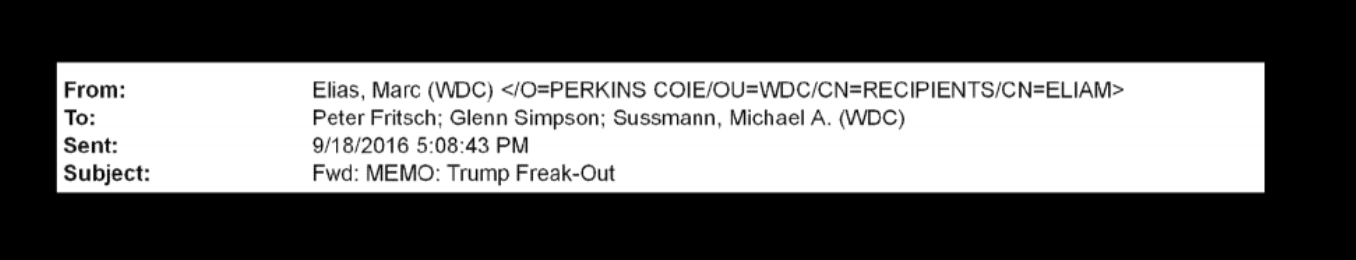

Take two exhibits from the trial as an example. Durham is making much of a September 15, 2016 email from Marc Elias to top people on the campaign. Its subject line was “Alfa article.” But it appears to be sharing an article about “testimony of an oil trader.” If Sussmann could share it, it might simply show that Elias had seen an article about corruption and seen some tie with the Alfa Bank allegations. He can’t, because Elias is the one who made that connection.

Meanwhile, two exhibits Sussmann introduced into evidence show Robby Mook — who is not a lawyer — sharing Sidney Blumenthal “intelligence” with him that the Trump campaign was freaking out because they had gotten advance word of a NYT article about Trump’s ties with Russia.

The Trump campaign is having “a major league freak-out,” according to a Republican source who has been reliable in the past. What is causing the Trump “freak-out” is anticipation of an investigative story to be published by the New York Times. The subject is described as “Russia” and “a disaster.” “That is completely the story of everything going on since Thursday,” insists the source. The Times story, says the source, accounts for Tramp’s extraordinarily defensive aggressive reactions–his declaration that he will sue the New York Times, his personal tweeting attack on Maureen Dowd as “wacky” and a neuSidney rotic dope,” (though the source says “that’s just him anyway”), his call for the assassination of HRC, and the campaign’s push to the media of the flat-out lie that I was behind birtherism in 2008. On Saturday night, Trump tweeted: “My lawyers want to sue the tailing @nytimes so badly for irresponsible intent. I said no (for now), but they are watching. Really disgusting.” Trump did not specify why the Times might be guilty of”irresponsible intent,” which in any case lacks any legal weight. Earlier on Saturday, he tweeted that the Times was “a laughingstock rag.” The atmosphere inside the campaign is described as chaotic, frenetic and “spontaneous.” Bannon and Bossie are said to be grasping at anything to throw back in order to distract from and fend off the coming story. Journalistic sources have independently said that reporters at the Times are working on a Tromp-Russia story.

It wouldn’t be a high profile political trial, I guess, if Sid Blumenthal didn’t make a showing. Note that Mike Flynn’s Mueller interviews show him responding to some Sid Blumenthal stuff in precisely this period, so it’t clear Sid was talking to Republicans.

Anyway, that part — Blumenthal sharing with Mook — was not privileged. And that part makes it clear that Elias was right to be concerned about Trump suing if the Hillary campaign made factual observations about his ties with Russia. It also may (though this is uncertain) back Sussmann’s understanding that Eric Lichtblau was close to publishing the Alfa story, so close that Trump’s moles at the NYT had alerted him to it. But whatever Mook said about it to Elias, the campaign’s lawyer guarding against lawsuits, is privileged, as whatever Elias said to Sussmann and the Fusion guys when he forwarded Mook’s comment would be.

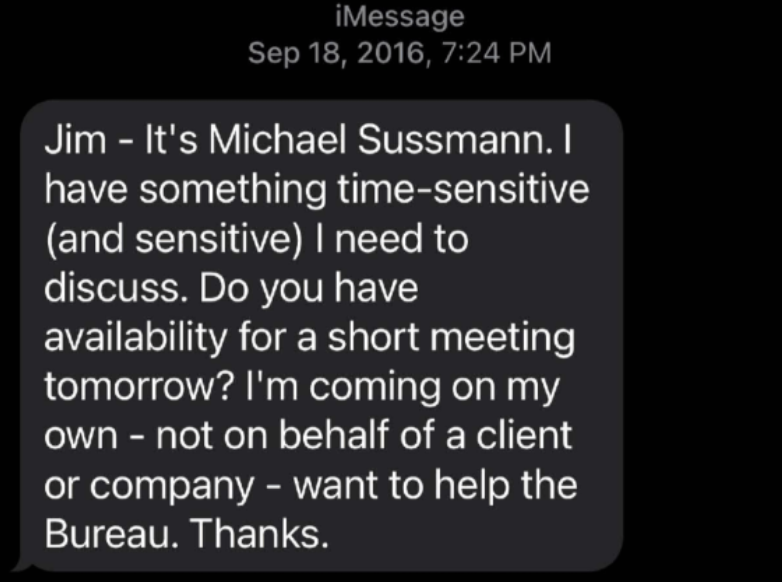

Whatever was said may have influenced Sussmann’s decision to go to the FBI, though, as this was shortly before he texted Jim Baker and asked to meet.

In his testimony, Elias stated that he had not given Sussmann permission to go to the FBI with the Alfa Bank story. He doesn’t think he knew until shortly afterwards, though could have learned before (the Blumenthal story may serve to explain a call that Sussmann knows prosecutors plan to dramatically reveal).

You testified that you became aware that Mr. Sussmann went to the FBI. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And your testimony was that you think that you were told right after, although there’s a possibility it was right before?

A. Yes.

Q. Your best recollection is which of those?

A. Is after.

Q. Okay. Did you tell him to go to the FBI?

A. No.

Q. Did he seek your permission to go to the FBI?

A. No.

Q. Did you authorize him to go to the FBI?

A. No.

Q. Are you aware of anyone at the Clinton Campaign that authorized Mr. Sussmann to go to the FBI to share the possibility of The New York Times story?

A. Not that I’m aware of. No.

Q. Did you consent to his going to the FBI?

A. No, not that I remember. No.

Elias even explained what a colossally bad idea it would be for a candidate whose campaign had been badly damaged by Jim Comey to go to the FBI.

A. First of all, the FBI had in my view not been particularly helpful in investigating or doing anything to prevent the leaks of the emails. The exfiltration is one thing, you know, the stealing of the emails. But the publication of the emails, it was not just this one time. I mean, we were dealing with multiple publications of emails. And it was not just this one client.

And I think my sense was that the FBI was not for a variety of reasons going to do anything that was going to be — like stop bad things from happening, which would be one reason to go for the FBI.

The second, which is more unique to the Clinton Campaign, is that I think he was then the FBI director, but James Comey had taken public stances in around that time period that were in my view unfair and putting a thumb on the scale against Secretary Clinton.

So I’m not sure that I would have thought that the FBI was going to be — give a fair shake to anything that they viewed as anti-Trump or pro-Clinton.

And then the final thing is that if The New York Times was going to run this story, like that’s the goal. Right? The New York Times runs the story. If you get the FBI involved, any number of things could prevent that from happening. Right?

In the most extreme instance, the FBI can go to the publication and say: Please don’t. But the second is, the newspaper itself might then want to do further reporting on the FBI investigation and delay its story. Right?

So, like, even in a world in which, like, the FBI is being helpful — not being helpful; even in a world in which the FBI is doing stuff, the media may not run the story because they want to get the full picture because they view the FBI piece of it as an essential piece of the story.

It’s certainly possible that, given this advance warning of a Trump shit-storm, Sussmann decided it would be best to give FBI a head’s up. Sussmann, however, can’t ethically share the communications between Elias and him, even if it would help him. That’s how privilege works.

With that in mind, consider what Shaw said in Durham’s bid to keep Eric Lichtblau off the stand (this appears to have been filed two days after Judge Cooper ordered it, but one of the Durham lawyers has had a family emergency so they may have gotten an extension).

After explaining that prosecutors need to question Lichtblau about things the scope of which have been specifically excluded in the trial, a footnote claims that they won’t violate Judge Cooper’s rules about such things (they have, serially, during the trial).

The government should be permitted to cross-examine Lichtblau about any communications he had with other individuals, including, but not limited to, Fusion GPS personnel and computer researchers, regarding the alleged connections between the Trump Organization and Alfa bank. To the extent Sussmann, Fusion GPS, or others (including computer researchers) approached or communicated with Lichtblau concerning Alfa Bank or related matters, the government should be permitted to question Lichtblau about such exchanges, as they are relevant to the defendant’s communications with Lichtblau on these same issues and are probative of the defendant’s alleged actions on behalf of clients (Rodney Joffe and the Clinton Campaign). The government also intends to cross-examine Lichtblau on issues pertaining to the credibility and reliability of his testimony. 1

[snip]

If Fusion GPS (which was hired by the defendant’s firm on behalf of the Hillary for America Campaign) and other persons known to Joffe and/or Sussmann similarly supplied opposition research-type information to Lichtblau regarding the Trump Organization as a part of a coordinated effort, this would be relevant to demonstrate that Sussmann was not acting merely as a concerned citizen trying to help the FBI when he met with FBI General Counsel and that his contrary representations were false. Indeed, the Government is aware that Sussmann and Joffe did enlist and/or task one or more other computer researchers to communicate with the media (including Lichtblau) concerning these matters

1 The government will abide by the Court’s order of May 7, 2022 and, in accordance with that order, will not “put on extensive evidence” about the accuracy of the data provided by Sussmann or his clients to the FBI, Lichtblau, or others. See Op. & Order (“In Limine Order”) at 5, ECF No. 121. [my emphasis]

Here, Shaw states as fact that the computer research was opposition research. It was not.

I am 100% certain that if Lichtblau could testify about all the people he spoke with on this story, he could explain that many if not most of the people involved — as well as a bunch of other people, including at least one whom prosecutors have affirmatively claimed did not have a role in chasing down this anomaly — believed the anomaly was real and were motivated out of a genuine alarm about the Russian attack that year. Yes, the NYT found people who pushed back (more so after the FBI killed the story). But that’s what makes Lichtblau’s work reporting, not opposition research.

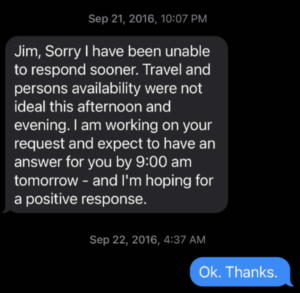

If Lichtblau is able to testify, he could also provide a key piece of important context to evidence the government has already presented. Yesterday, Jim Baker described how, starting on September 21, he reached out to Sussmann for the name of the reporter working on the story.

Baker provided Lichtblau’s name to Bill Priestap before noon on September 22. But Lichtblau didn’t meet with the FBI until Monday, September 26.

We know that in between, the FBI called Cendyn, leading them to alter their DNS address, and the NYT called a representative for Alfa Bank which later — NYT believed, at least — led Alfa to alter their DNS address. The NYT believed that there was a response from Alfa that indicated they were trying to hide this activity.

A key part of Durham’s claim is that NYT wasn’t close to publishing when Sussmann went to the FBI and that Sussmann was, instead, trying to provide urgency for the story. That doesn’t accord with my understanding and it doesn’t accord with what Dexter Filkins has written. Durham can keep telling it so long as Lichtblau doesn’t testify.

One thing that happened, though — in addition to initial contacts that would have alerted Lichtblau that the FBI didn’t want him to publish — was the response to those calls after Sussmann and Joffe decided to share Lichtblau’s name. There was new news that Lichtblau had to try to understand that created a new delay.

As with Sussmann, it would be nice for Lichtblau if he could describe all the efforts he made to verify the story. If he could, it would demonstrably undercut several of the claims Durham is making. He can’t, because he has separate confidentiality agreements with those other sources.

Shaw, who accuses Sussmann of being privileged, completely flips how privilege works on its head (including by mis-citing the David Tatel concurrence in the Judy Miller subpoena, which as I understand it would support Lichtblau making the call about the scope of his testimony). She ties it to a topic rather than a privileged relationship to accuse Lichtblau of trying to selectively pick which parts of the story he can tell.

The D.C. Circuit has “declined to adopt a selective waiver doctrine” in the context of attorney-client communications that “would allow a party voluntarily to produce documents covered by the attorney-client privilege to one party and yet assert the privilege as a bar to production to a different party.” United States v. Williams Companies, Inc., 562 F.3d 387, 394 (D.C. Cir. 2009). “The client cannot be permitted to pick and choose among his opponents, waiving the privilege for some and resurrecting the claim of confidentiality to obstruct others.” Permian Corp. v. United States, 665 F.2d 1214, 1221 (D.C. Cir. 1981). Privilege holders must instead “treat the confidentiality of attorney-client communications like jewels—if not crown jewels” because courts “will not distinguish between various degrees of ‘voluntariness’ in waivers of the attorney-client privilege.” In re Sealed Case, 877 F.2d 976, 980 (D.C. Cir. 1989).

This principle—which restricts a privilege of “ancient lineage and continuing importance,” In re Sealed Case, 877 F.2d at 980—necessarily governs the novel and qualified reporter’s privilege advanced in this case. Sussmann subpoenaed Lichtblau to appear as a witness and Lichtblau has not moved to quash. Lichtblau and defendant Sussmann cannot “tactical[ly] employ[]” the asserted privilege to pick and choose the topics that may be put to Lichtblau on the witness stand. Permian Corp., 665 F.2d at 1221. Privileges are not “tool[s] for selective disclosure.” Ibid

I get why someone in the grips of a fevered conspiracy theory would make this argument. Durham believes that everyone involved with the Alfa Bank story was part of the same malicious conspiracy targeting poor Donald Trump, even though DOJ has in its possession abundant proof that’s false. Yet even in this case, Cooper has distinguished between the privileged relationships that Joffe has with what the Democrats have, and he has also pointed to affirmative evidence that this wasn’t one big conspiracy.

But Shaw would have you believe that Lichtblau’s privilege obligations are tied to a project, a story, and not a bunch of individuals, many of whom he had existing relationships with well before this story.

A lawyer not in the grip of a fevered conspiracy theory, however, would understand that that kind of privilege doesn’t make you special, it creates an obligation, even if the obligation prevents you from using your profession from helping yourself.