John Durham’s Show Trials: A Preview of Coming Attractions

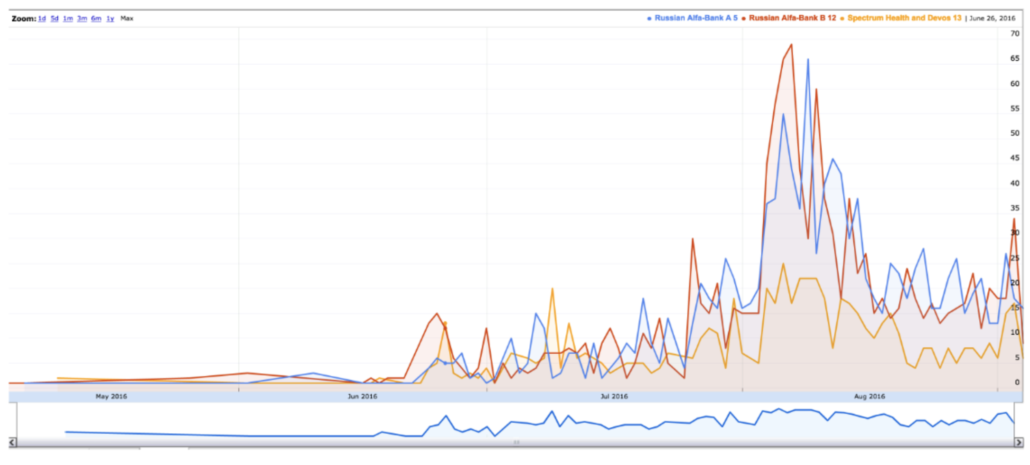

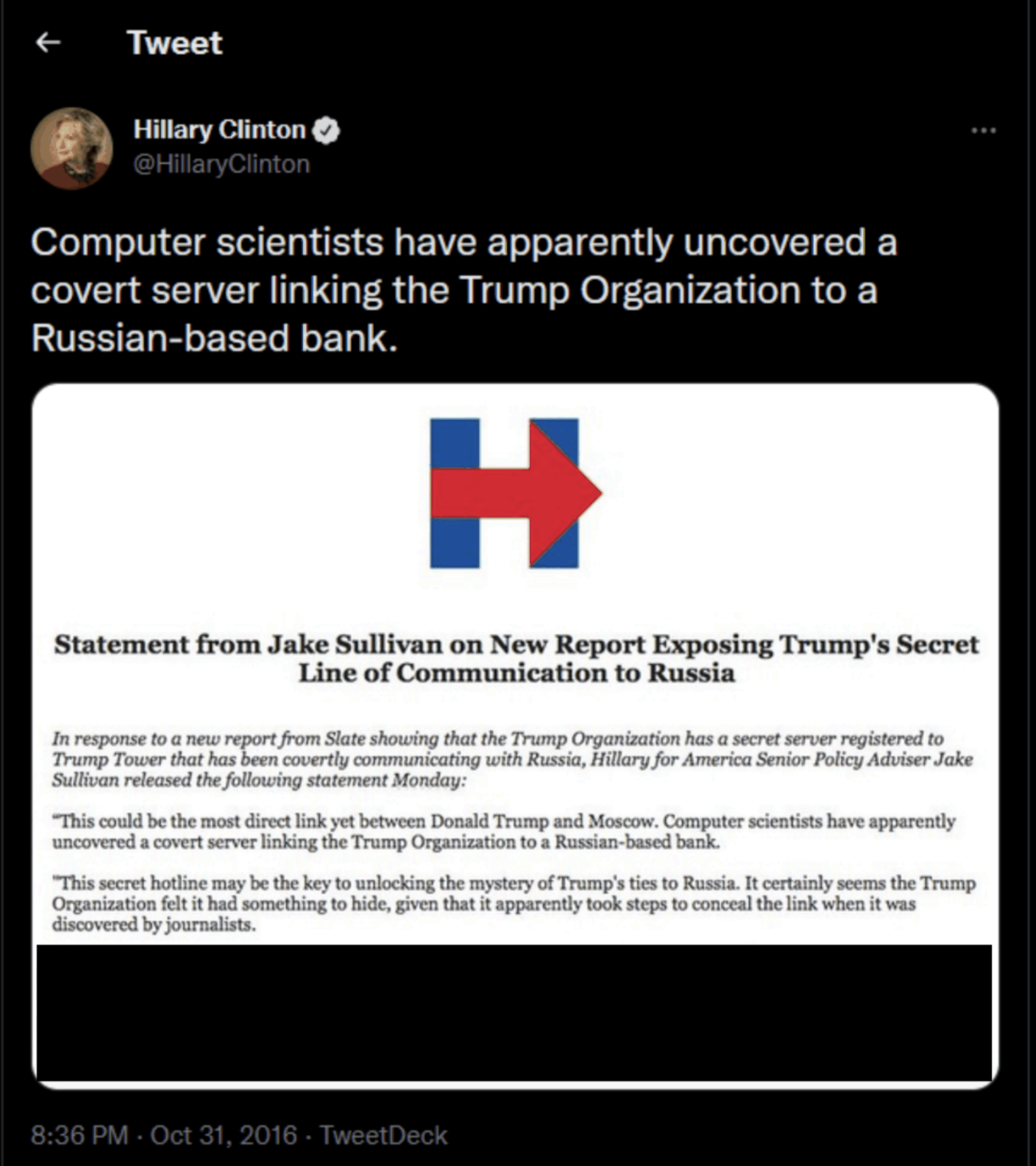

On May 20, 2022 — a year after John Durham had obtained evidence showing that the draft SVR report that he always claimed was the basis of his investigation was based on “composite” emails, and as such, proof that the SVR was framing Hillary Clinton — his lead prosecutor, Andrew DeFilippis, openly defied a judge’s order. DeFilippis instructed Hillary Clinton’s former campaign manager, Robby Mook, to read a quote from Jake Sullivan about the Alfa Bank anomalies saying, “This secret hotline may be the key to unlocking the mystery of Trump’s ties to Russia. It certainly seems the Trump Organization felt it had something to hide, given that it apparently took steps to conceal the link when it was discovered by journalists.”

The quote seemed to confirm the conspiracy theory that Durham had otherwise failed to substantiate, that Hillary had a plan to frame Donald Trump.

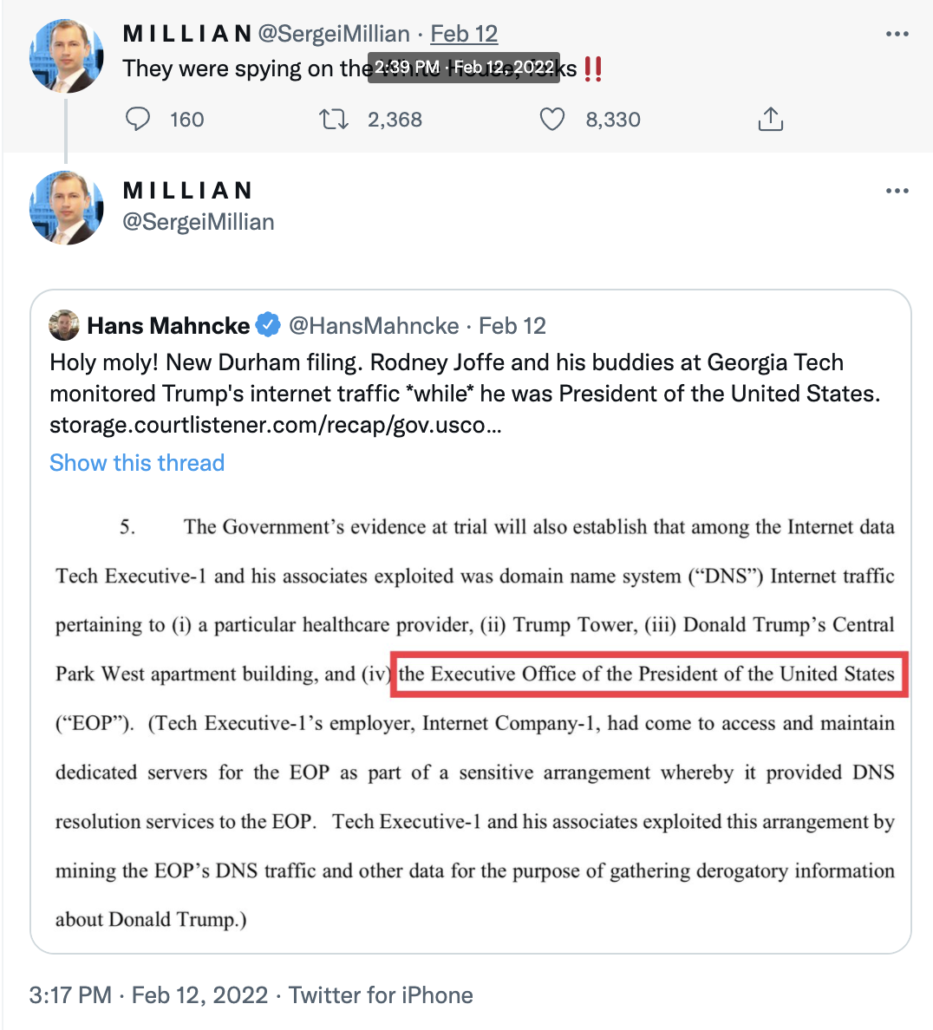

The inclusion of the Tweet as trial evidence immediately created a firestorm among credulous journalists, leading right wingers, including Elon Musk, to claim this was proof of “an elaborate hoax about Trump and Russia.”

DeFilippis’ stunt introducing prejudicial hearsay he had just been ordered to exclude led to a redaction of the transcript and Tweet he contemptuously had Mook read. But, as Sussmann’s lawyer complained after Durham’s team pulled several more stunts like this, “the bell” of hearing prohibited testimony, “can never be unrung.” By cheating, Durham’s team presented six elements of the conspiracy theory based on the SVR attack on Hillary to the jury, in spite of rulings prohibiting them from doing so.

It didn’t help his case; less than two weeks later, a jury returned a humiliating acquittal, the first of two.

Yet Durham broke the rules to tell his manufactured story, and it worked in the public sphere.

Trump prosecutors already staged show trials

The prosecution of Michael Sussmann should never have gotten that far. Once Durham had the evidence to conclude that the emails behind the draft SVR report he claimed to be working off of were “composites,” he should have closed up shop. Instead, he charged Michael Sussmann and Igor Danchenko in an effort to sustain the story imagined by Russian spies five years earlier anyway.

Durham’s goals with Danchenko were modest (and fairly pathetic): to attempt to rewrite the genesis of the Steele dossier to make the business networking of a Democrat — and not Russian sources — the author of key claims in the dossier, and to attempt to turn Sergei Millian into the victim of the Steele dossier. After the judge in the case threw out one charge because Durham had charged Danchenko for lying about the pee tape in a literally true response he gave to an FBI question, the jury acquitted on four other counts pertaining to Millian.

Durham’s goals with Sussmann were far more ambitious: to use a single invented false statement as a lever to get inside Democratic networks to find the conspiracy that — even after concluding that the genesis of his entire investigation was an SVR fabrication — Durham nevertheless still believed had to exist.

It was utter madness. It was an egregious abuse of Sussmann’s rights — as I said here, Durham committed the precise crime that he claimed to be hunting. And it serves as a roadmap for where the sequel investigation Pam Bondi just announced might go.

In part because it serves as a roadmap for the stunt prosecutions Trump is ordering up, I want to take two posts to describe what happened. This post will use known interviews and my coverage of both cases — see also this earlier post attempting a similar project — to review the tactics Durham used to get this case to trial. In a follow-up, I hope to show how Durham’s show trials failed.

Pivot

What should have been the two final interviews on Durham’s Clinton conspiracy conspiracy theory investigation — the July 21 interview in which Julianne Smith disclaimed any knowledge of the Clinton plan and a July 8 2021 grand jury appearance where Peter Strzok denied receiving a referral mentioning it — happened almost five years after the events in question. The clock on any 5-year state of limitation was ticking.

So Durham pivoted.

The closest Durham came in his report to offering an explanation for why he continued after concluding these documents were fabricated came from speculation offered up by Brian Auten, the lead analyst on the team (and a MAGAt target ever since). At a time Durham knew he had no proof that the CIA referral to FBI had actually gotten to the Crossfire Hurricane team, he invited Auten to speculate.

Auten stated that it was possible he hand-delivered this Referral Memo to the FBI, as he had done with numerous other referral memos,419 and noted that he typically shared referral memos with the rest of the Crossfire Hurricane investigative team, although he did not recall if he did so in this instance. 420

[snip]

For example, Brian Auten stated that he could not recall anything that the FBI did to analyze, or otherwise consider the Clinton Plan intelligence, stating that it was “just one data point.”423

419 OSC Report of Interview of Brian Auten on July 26, 2021 at 13.

420 Id.

[snip]

423 OSC Report of interview of Brian Auten on July 26, 2021 at 13.

That interview was on July 26, 2021, at precisely the moment Durham should have packed up and gone home.

But consider the circumstances of that interview. At the Danchenko trial, Danchenko’s attorney Danny Onorato started his cross-examination of Auten by getting the FBI analyst to recall how — after his testimony in numerous other investigations was deemed credible — Durham started his first interview with Auten by informing him he was considered a subject of the investigation. (In that interview and one shortly thereafter, Durham seems to have used the threat of charges relating to the Carter Page FISA warrants to threaten Auten and one of the Crossfire Hurricane agents, precisely the theory of criminality that his investigation started to violate in those days.)

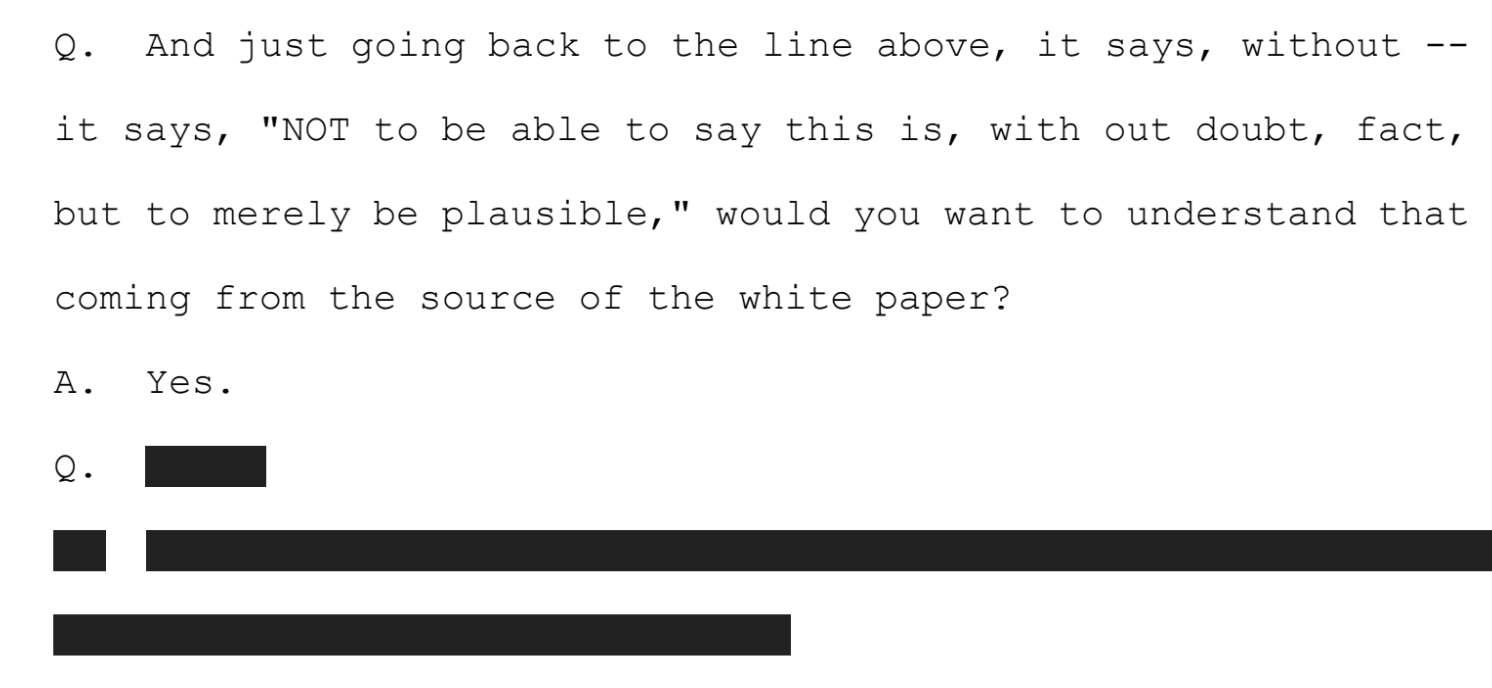

Q Does July 26 of 2021 sound fair?

A Yes, it does.

Q Okay. And when you met with them for the first time after you were meeting with people for 25 or 30 hours, did your status change from a witness to a subject of an investigation?

A Yes, it did.

Q Okay. And in your work for the FBI, has anyone ever told you that you are a subject of a criminal inquiry? A No.

Q Was that scary?

A Yes.

Hours later, after having walked Auten through a long list pertinent things Durham had not shown Auten when soliciting specific answers that incriminated Danchenko, including part of Auten’s own notes that he had underlined, Onorato got Auten to concede that his opinion about the credibility of Danchenko on the topic of Sergei Millian changed after that July 26, 2021 interview, in which he had been named a subject.

Yet even in that context, under threat of prosecution, Auten had no real memory of the referral and treated it as a data point if he actually did share it with Crossfire Hurricane. That’s what Durham rebuilt his debunked investigation on.

And having thus scripted an excuse to continue, Durham charged Sussmann on the very last day possible, September 16, 2021; he charged Danchenko in early November. As I wrote in those contemporaneous posts, both used ticky tack alleged lies to spin networked materiality claims insinuating a conspiracy that led sloppy journalists to adopt larger claims of conspiracy.

The belated investigation into false statements charged as a conspiracy

In the Sussmann case, Durham had been poring through subpoenaed documents from participants he imagined had played a part in his theory of conspiracy for over a year, but neither that nor immunized testimony from David Dagon in August had confirmed key premises of his conspiracy. Having failed to substantiate a conspiracy, then, Durham charged a different crime, a false statement charge. Such a belated change in prosecutorial strategy might explain how epically unprepared Durham was to prosecute the crime he actually charged. In the weeks and months that followed, Durham would serially confess he hadn’t taken some of the most basic investigative steps before indicting Sussmann, including:

- Interviewing any full-time Clinton campaign staffer before accusing Sussmann of coordinating with the campaign (he would interview Jennifer Palmieri, Jake Sullivan, Victoria Nuland, James Clapper, John Podesta, and — just days before jury selection — Hillary Clinton in the eight months that followed); Durham’s report doesn’t reflect a Robby Mook interview; he was called as a defense witness at trial

- Repeating FBI’s 2016 errors in belated interviews of DNS-related service providers

- Testing the story Sussmann told Congress, under oath: that he reached out to the FBI to alert them to a story before the NYT covered it, which turned out to be confirmed by documentary records Durham only belatedly found at FBI

- Learning how closely the FBI worked with Rodney Joffe on DNS-related issues

- Checking how closely Michael Sussmann worked with the FBI, especially on the response to the Russian hacks; this was especially egregious as it debunked one of the ways he tried to implicate Julianne Smith in a made-up plot

- Finding the January 31, 2017 CIA meeting record at which Sussmann clearly explained he was sharing an allegation at the request of a client

- Finding notes from a May 2017 that debunked Durham’s accusations

- Asking DOJ IG for evidence from their closely related investigation

- Discovering a similar DNS tip that Sussmann had anonymously shared with DOJ IG on behalf of Rodney Joffe

- Obtaining two James Baker phones, one of which Durham had been informed about years earlier

- Subpoenaing or seizing Baker’s iCloud account for the text which would debunk Baker’s early memories and confirm Sussmann’s explanation

- Searching FBI records for evidence that someone else — someone who once claimed to work for a Russian front company — had played a role Durham attributed to his conspirators

In short, Durham had little to sustain his 27-page indictment beyond theories of conspiracy that assumed as true the conspiracy theory he should have abandoned in July.

It really seems like, before that, Durham believed he would eventually find witnesses to a conspiracy who would confirm what only he believed to be true, and as a result never took the investigative steps that might — and did — debunk his conspiracy theory.

After embracing Russian disinformation, Durham embraced Russian grievances

One way Durham attempted to compensate for his failure to take very basic investigative steps was to embrace what Russians were peddling.

There were always hints that Durham went seeking (dis)information from Russians or people assumed to be Russian-assets involved in this operation. They was the famous junket to Italy looking for Joseph Mifsud. There were Ukrainians, who remain unnamed, but whose identity might explain why Durham reacted oddly when Andrii Derkach’s allies were sanctioned in early 2021. There’s even an email showing that future Charles McGonigal defense attorney Seth DuCharme treated Andrew McCabe request for help from Oleg Deripaska as an investigative lead, an email that might explain why Durham suppressed Deripaska’s centrality in this story.

But after he charged these flimsy indictments, Durham made purportedly aggrieved Russians a key prong of his strategy to turn a debunked Russian effort to frame Hillary into criminal prosecutions.

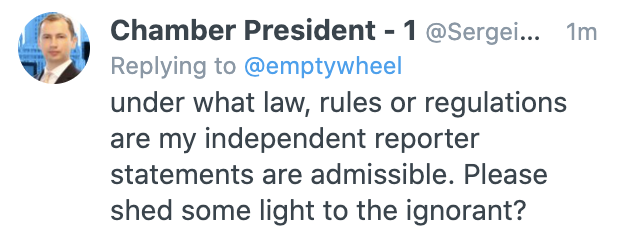

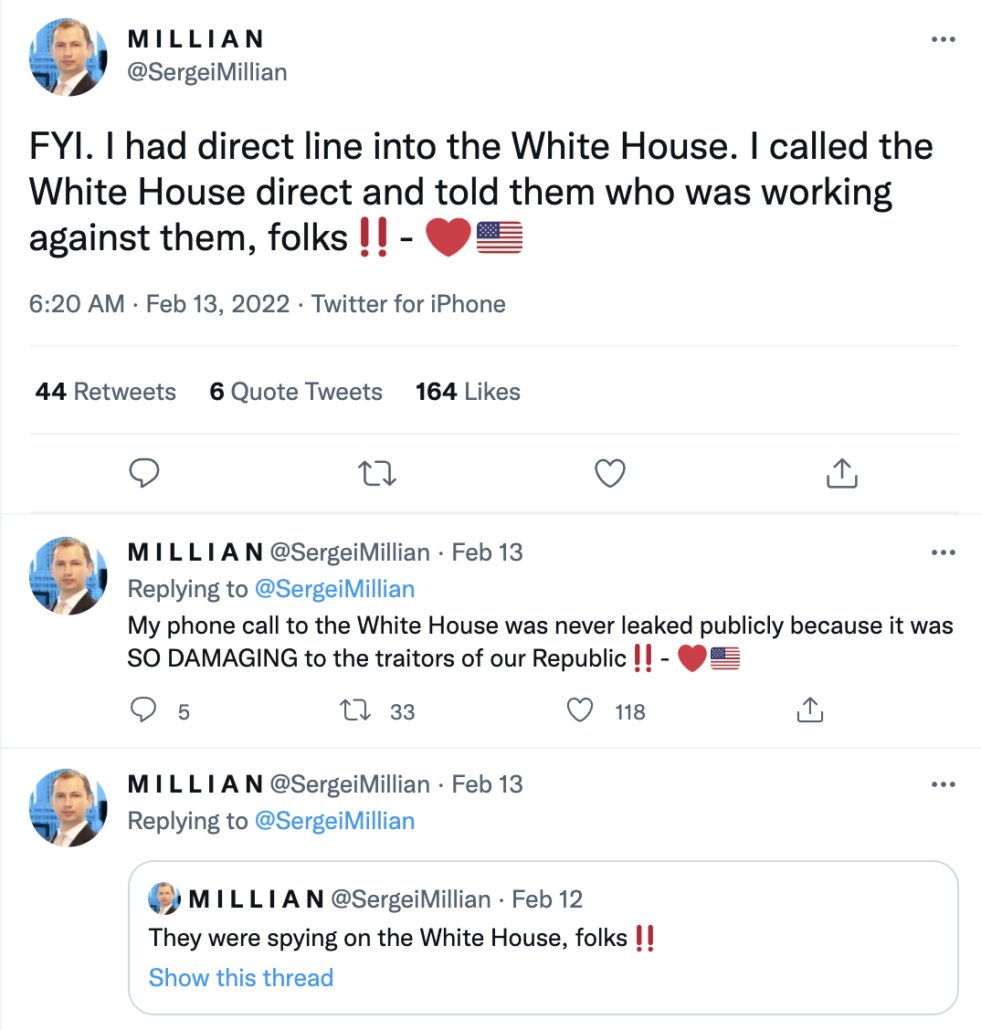

On the Danchenko prosecution, Durham insanely initially relied solely on Sergei Millian’s Tweets to substantiate the four charges associated with Millian. He did so without first interviewing George Papadopoulos, whom Millian seemed to be cultivating in precisely the period when Durham’s conspiracy theory was born and for months thereafter. As soon as I noted how problematic that was, Millian started getting squirrely.

Durham did eventually interview Millian, three months after charging Danchenko. But Millian refused to show up and answer questions under oath.

That left Durham stuck trying to admit inadmissible evidence, without which he was left with no substantive evidence for those four charges. All the while, Millian was ginning up the frothers, including (as we’ll see in my follow-up), to spin up Durham’s own misleading claims.

When Onorato introduced evidence of Millian’s communications with Papadopoulos at trial, Durham protested, “it certainly sounds creepy.” Nevertheless, Durham built four charges of an indictment around the Twitter claims of a guy involved in creepy outreach even before SVR’s imagined Clinton conspiracy was born, creepy outreach that by itself debunked the Russian conspiracy theory.

The way Millian handed Durham his ass would be funny if it didn’t totally upend Danchenko’s life.

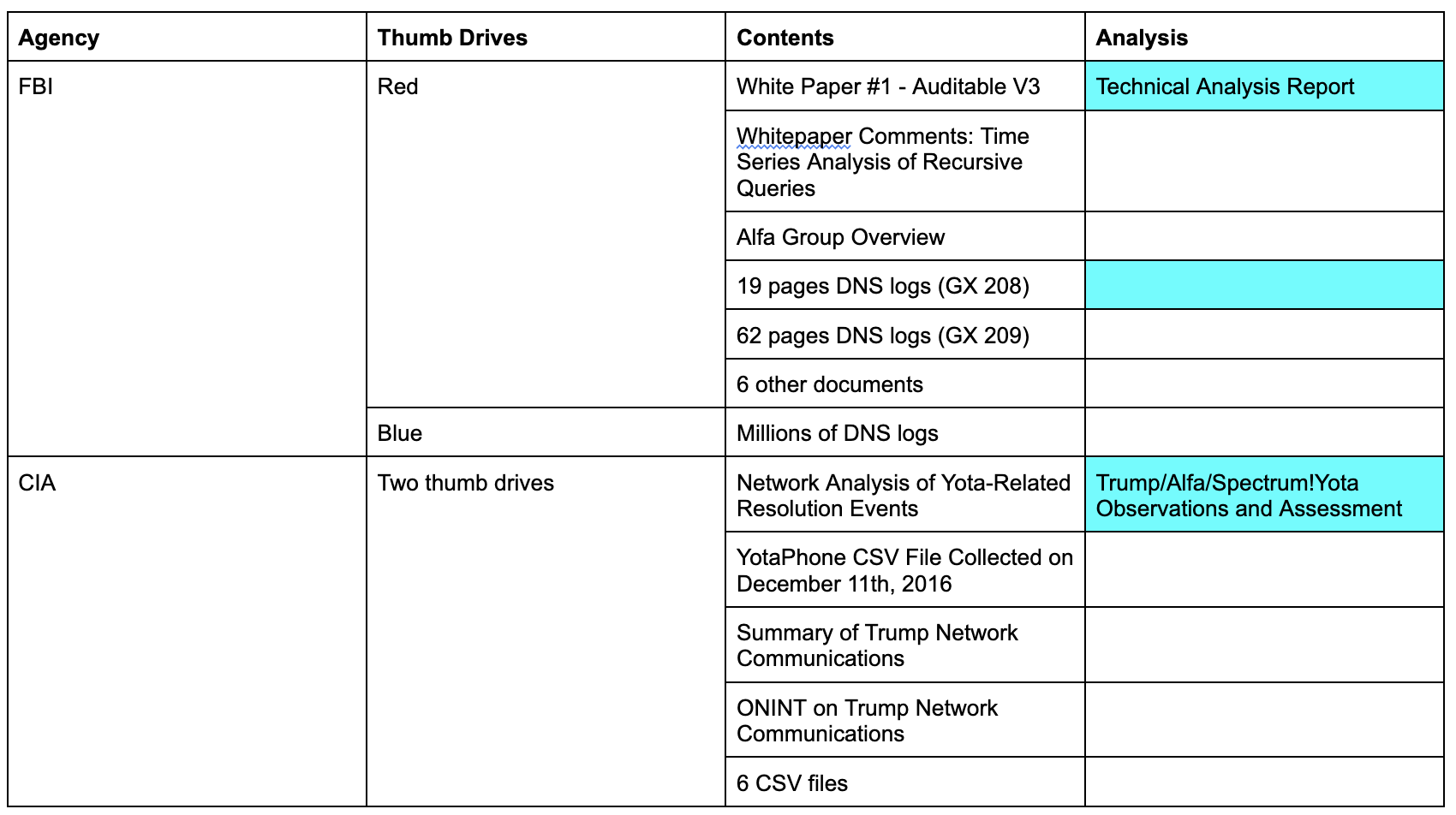

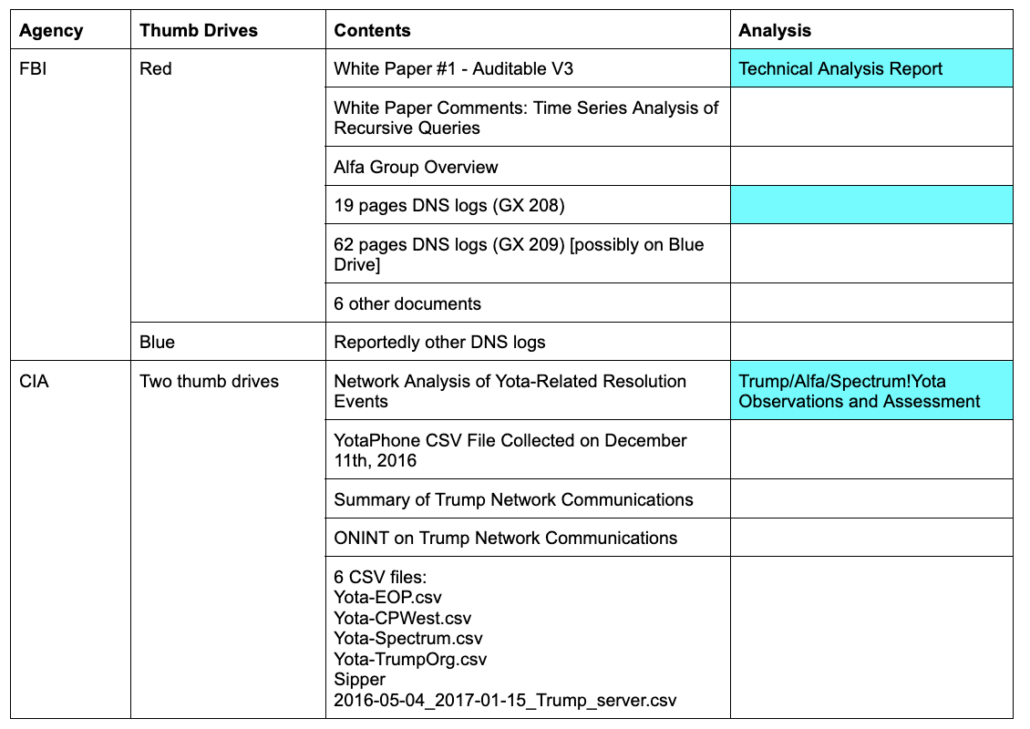

But the way Durham piggybacked on Alfa Bank’s lawfare (lawfare pursued long after Mueller described how Vladimir Putin would make demands of oligarchs like Alfa Bank’s Petr Aven) is more troubling. In dual lawsuits in FL and PA, Alfa Bank purported to be trying to figure out who allegedly faked DNS records to make it look like Alfa was in contact with Trump back in 2016 so it could sue those people. Rather than finding anyone to sue, however, it instead spent its time subpoenaing experts to learn as much as it could about how the US tracks DNS records to prevent cyberattacks by — among other hostile countries — Russia.

After the Sussmann indictment, Alfa deposed several people targeted in the Sussmann investigation, including Fusion GPS tech person Laura Seago (from whom Durham ultimately obtained immunized testimony at trial) and Rodney Joffe (who was one of Durham’s key targets). Durham used that information as a sword in later privilege fights, but ignored sworn denials of key parts of his conspiracy theory. When Alfa pushed to accelerate this process even in spite of the ongoing criminal investigation, DC Superior Judge Shana Frost Matini observed that claims in the Alfa Bank lawsuit and Durham’s indictment see like, “they were written by the same people in some way.”

[R]ight now, given the — if the closeness of Alpha’s allegations, I mean, quite frankly, it’s — reading Alpha’s submissions and what the — and that compared to the indictment, there’s — it’s almost like they were written by the same people in some way. [Alpha misspelling original]

In the Sussmann case, Durham seemed to be delaying steps he took much earlier in the Danchenko prosecution, as if he was waiting for Alfa Bank to do that work for him.

All that ended with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the sanctioning of Alfa Bank, which seemed to lead Durham to adopt a new strategy.

The Rodney Joffe statute of limitation

Two pieces of background are useful — particularly if Sussmann’s prosecution serves as a lesson of how Pam Bondi might try to wrench new prosecutions out of these same old tired events.

First, Durham went to great lengths to sustain his ability to charge Rodney Joffe, the source of the DNS records in question, which led Judge Charles Cooper to make a shitty ruling preventing Sussmann from calling Joffe to provide testimony that would entirely exonerate him. Durham was doing so, transparently, in hopes he might charge Joffe for a crime with a longer statute of limitations than lying: defrauding DOD.

But the successful bid to keep Joffe off the stand implicated something else: Durham’s attempt to suppress things he had discovered about the DNS data in question.

The month before Durham charged Sussmann, by mid-August, 2021, Durham’s team learned that the data Rodney Joffe and others used to conduct their research was absolutely real. In addition to debunking the most simplistic “DNC fabrication” theories Durham was chasing, the discovery made it impossible for Durham to continue to rely on the expert his team had been using.

The first thing Durham did in response was ask one of the two FBI agents who had fucked up the investigation in 2016 — the other of whom is a possible source of Durham’s false claim that the SVR conspiracy theory about Hillary claimed she was going to fabricate evidence against Trump — to serve as an expert to replace the one who knew Durham’s theories were false.

DeFilippis. How familiar or unfamiliar are you with what is known as DNS or Domain Name System data?

A. I know the basics about DNS.

[snip]

Berkowitz. And then, more recently, you met with Mr. DeFilippis and I think Johnny Algor, who is also at the table there, who’s an Assistant U.S. Attorney. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. They wanted to talk to you about whether you might be able to act as an expert in this case about DNS data?

A. Correct.

Q. You said, while you had some superficial knowledge, you didn’t necessarily feel qualified to be an expert in this case, correct, on DNS data?

A. On DNS data, that’s correct.

After that, Durham sought out another (legit) expert, but asked him to do a review that deliberately blinded him to what Joffe, through Sussmann, had shared with the government.

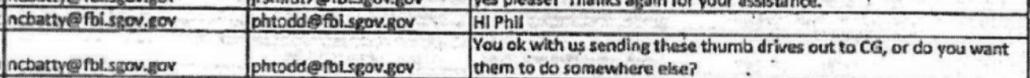

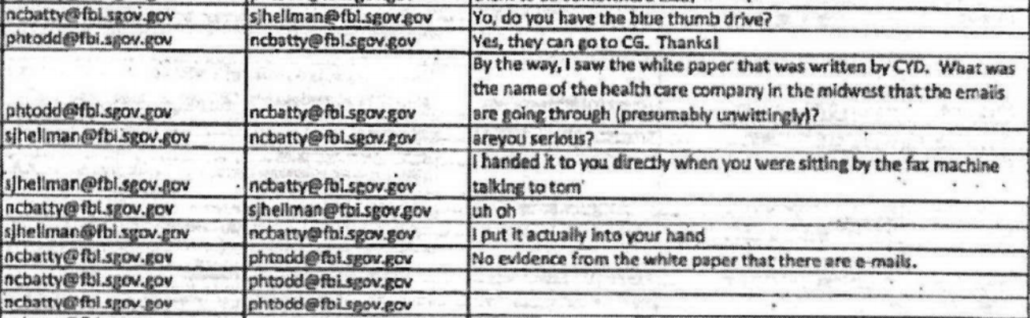

The only thing the FBI’s top experts offer to debunk, other than the Tor node claim that the FBI knew the researchers had dropped, was a complaint about visibility. But their complaints about visibility were entirely manufactured by the scope of the review Durham requested and possibly by the curious status of the Blue Thumb Drive, as well as (if Durham is telling the truth about these being the same experts) willful forgetting of a review they had done on related issues less than a year earlier.

Durham created this blindness. By ensuring all the experts remain blind to visibility, Durham ensured the review would conclude that the researchers didn’t have the visibility that, the FBI knew well, they had.

So in parallel with Durham’s efforts to sustain an SVR hoax he had debunked in July 2021, he went to great length to invent false claims about real data to sustain a judgement from the two FBI Agents who fucked up this investigation in the first place. He did so at the last minute, long after he should have finalized his plans for expert witnesses.

Abusing privilege

He did one more thing at the last minute: he asked Judge Cooper to review a documents for privilege.

As NYT reported back in 2023, Durham started playing games with his DC grand jury not long before he concluded the entire SVR thing was a fabrication. After then-Chief Judge Beryl Howell rejected a bid to get a warrant for Leonard Benardo’s emails, they obtained them via the Open Society Fund directly, perhaps on threat of subpoena.

Mr. Durham set out to prove that the memos described real conversations, according to people familiar with the matter. He sent a prosecutor on his team, Andrew DeFilippis, to ask Judge Beryl A. Howell, the chief judge of the Federal District Court in Washington, for an order allowing them to seize information about Mr. Benardo’s emails.

But Judge Howell decided that the Russian memo was too weak a basis to intrude on Mr. Benardo’s privacy, they said. Mr. Durham then personally appeared before her and urged her to reconsider, but she again ruled against him.

Rather than dropping the idea, Mr. Durham sidestepped Judge Howell’s ruling by invoking grand-jury power to demand documents and testimony directly from Mr. Soros’s foundation and Mr. Benardo about his emails, the people said. (It is unclear whether Mr. Durham served them with a subpoena or instead threatened to do so if they did not cooperate.)

Rather than fighting in court, the foundation and Mr. Benardo quietly complied, according to people familiar with the matter. But for Mr. Durham, the result appears to have been another dead end.

A month before trial (and just weeks after the newly sanctioned Alfa Bank gave up its lawsuits), as part of a request that Cooper review the privilege claims that the Democrats, Joffe, and Fusion had made, Durham revealed he had been bypassing Howell.

In response, Sussmann accused Durham of abusing the same grand jury process he abused with Benardo (abuse, ironically, that debunked Durham’s conspiracy theory).

First, the Special Counsel’s Motion is untimely. Despite knowing for months, and in some cases for at least a year, that the non-parties were withholding material as privileged, he chose to file this Motion barely a month before trial—long after the grand jury returned an Indictment and after Court-ordered discovery deadlines had come and gone.

Second, the Special Counsel’s Motion should have been brought before the Chief Judge of the District Court during the pendency of the grand jury investigation, as the rules of this District and precedent make clear.

Third, the Special Counsel has seemingly abused the grand jury in order to obtain the documents redacted for privilege that he now challenges. He has admitted to using grand jury subpoenas to obtain these documents for use at Mr. Sussmann’s trial, even though Mr. Sussmann had been indicted at the time he issued the grand jury subpoenas and even though the law flatly forbids prosecutors from using grand jury subpoenas to obtain trial discovery. The proper remedy for such abuse of the grand jury is suppression of the documents.

Fourth, the Special Counsel seeks documents that are irrelevant on their face. Such documents do not bear on the narrow charge in this case, and vitiating privilege for the purpose of admitting these irrelevant documents would materially impair Mr. Sussmann’s ability to prepare for his trial.

He also revealed that some of those privilege claims went back to August — that is, the weeks after Durham should have closed up shop.

Email from Andrew DeFilippis, Dep’t of Just., to Patrick Stokes, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, et al. (Aug. 9, 2021) (requesting a call to discuss privilege issues with a hope “to avoid filing motions with the Court”); Email from Andrew DeFilippis, Dep’t of Just., to Patrick Stokes, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, et al. (Aug. 14, 2021) (stating that the Special Counsel “wanted to give all parties involved the opportunity to weigh in before we . . . pursue particular legal process, or seek relief from the Court”). And since January— before the deadline to produce unclassified discovery had passed—the Special Counsel suggested that such a filing was imminent, telling the DNC, for example, that he was “contemplating a public court filing in the near term.” Email from Andrew DeFilippis, Dep’t of Just., to Shawn Crowley, Kaplan Hecker & Fink LLP (Jan. 17, 2022). [my emphasis]

In a hearing on May 4, right before trial, Joffe’s lawyer revealed they had demanded Durham press a legal claim much earlier, in May 2021.

MR. TYRRELL: So if they wanted to challenge our assertion of privilege as to this limited universe of documents — again, which is separate from the other larger piece with regard to HFA — they should have done so months ago. I don’t know why they waited until now, Your Honor, but I want to be clear. I want to say without hesitation that it’s not because there was ever any discussion with us about resolving this issue without court intervention.

THE COURT: That was my question. Were you adamant a year ago?

MR. TYRRELL: Pardon me?

THE COURT: Were you adamant a year ago that —

MR. TYRRELL: Yes. We’ve been throughout. We were not willing to entertain resolution of this without court intervention.

THE COURT: Very well.

Ultimately, Cooper did bow to Durham’s demand, but prohibited them from using those documents at trial.

That didn’t prevent DeFilippis from attempting to use the privileged documents to perjury trap his one Fusion witness, the kind of perjury trap that might have provided a way to continue the madness indefinitely.

There must have been nothing interesting there: most of the Fusion documents were utterly irrelevant to the Sussmann charges, but could implicate the Danchenko ones, but Durham didn’t use them there, nor did he explain their content in his final report.

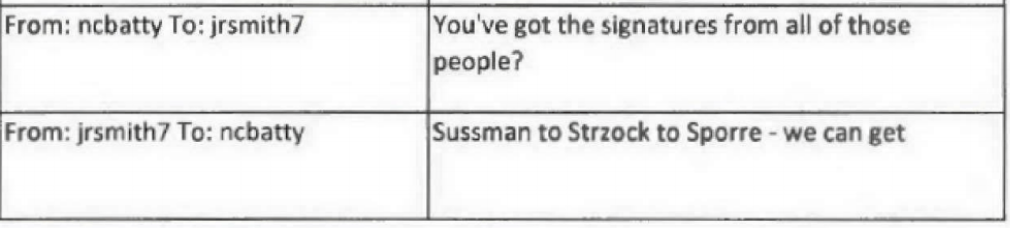

Scripting witnesses

I’ll end where I begin: How Durham managed to coach witnesses testimony by threatening them with charges.

In addition to Auten, Durham did this, over and over again, with his star Sussmann witness Jim Baker.

Perhaps most interestingly, he did it in the weeks before trial with witnesses who, documentary evidence showed, had been informed or would have assumed that Michael Sussmann was representing the DNC, the key thing Durham claimed Sussmann could have credibly lied to hide.

The first time FBI Agent Ryan Gaynor testified to John Durham in October 2020, for example, he told prosecutors that the DNC was the source of the allegation.

Q. Okay. So in your first meeting with the government, you — this is October of 2020, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. You told them multiple times that you believed that the Democratic National Committee was the source of the allegations of connections between Alfa-Bank and Russia, correct?

A. Correct, which was wrong.

Q. Okay. But you said that you thought the Democratic party itself was who provided the information, correct?

A. I did say that in the meeting.

That’s even what he wrote in a briefing document he kept in Fall 2016.

At the end of that October 2020 interview, prosecutors threatened Gaynor with prosecution.

In trial prep testimony, however, starting on May 13, 2022, he came to claim to believe that Sussmann was representing himself, because otherwise his client would have been material — precisely the materiality claim Durham needed to make the charges stick.

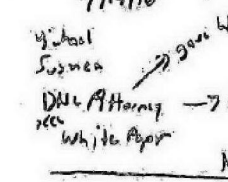

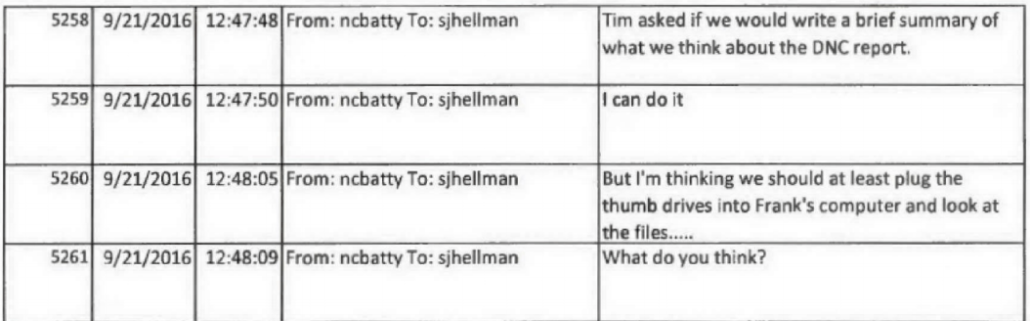

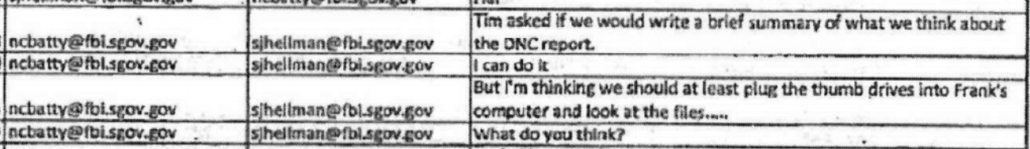

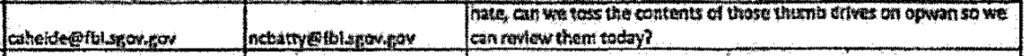

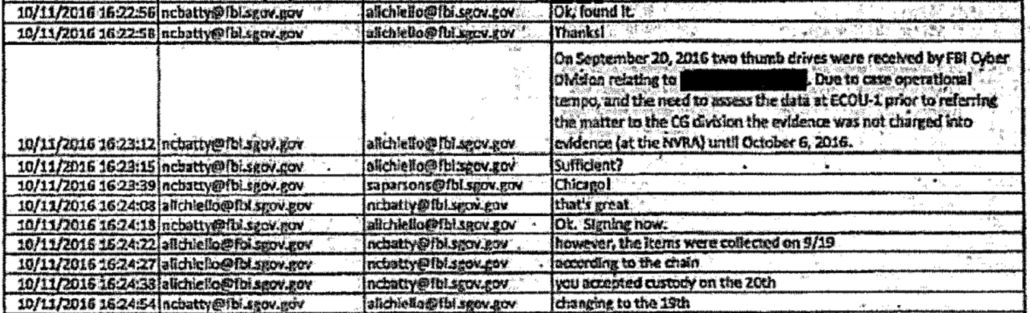

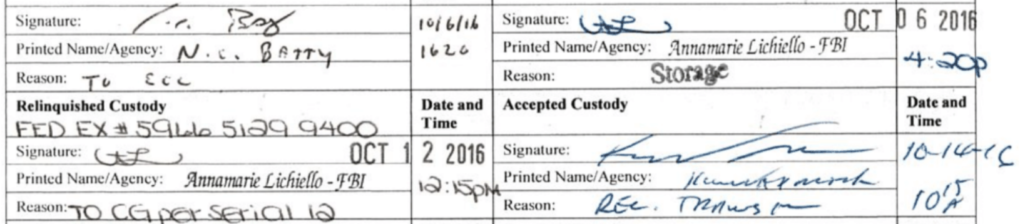

More striking was how Durham’s star cyber witness (one of the guys who botched the investigation in September 2016 without examining the data closely) explained why the text he received from his boss, Nate Batty, referring to the white paper as a “DNC report” on September 21, 2016, didn’t amount to notice that Sussmann brought the report on behalf of the DNC.

At trial, Michael Sussmann lawyer Sean Berkowitz asked Hellman how it could be that he would see a reference to a DNC report and not take from that it was a DNC report. Hellman described “the only explanation that … was discussed” — which is that it was a typo.

Q. What’s your explanation for it?

A. I have no recollection of seeing that link message. And there is — have absolutely no belief that either me or Agent Batty knew where that data was coming from, let alone that it was coming from DNC. The only explanation that popped or was discussed was that it could have been a typo and somebody was trying to refer to DNS instead of DNC.

Q. So you think it was a typo?

A. I don’t know.

Q. When you said the only one suggesting it — isn’t it true that it was Mr. DeFilippis that suggested to you that it might have been a typo recently?

A. That’s correct.

Q. Okay. You didn’t think that at the time. Right?

A. I did not. I had never seen it or had any memory of seeing it ever before it was put in front of me.

With some prodding, Hellman admitted that when he referred to “discussing explanations,” he meant doing so with Andrew DeFilippis. This exchange was, quite literally, Berkowitz eliciting Hellman to describe that DeFilippis told him what to think about evidence that should have sunk his case years earlier.

As I said, DeFilippis cheated. With lesser attorneys or more exhausted witnesses, it might have worked.

And they’re about to try again.