The extradition request and indictment have been pending while Vault 7 and Roger Stone have percolated

According to a BuzzFeed report from yesterday’s bail hearing in London, Julian Assange’s extradition warrant was dated December 22, 2017.

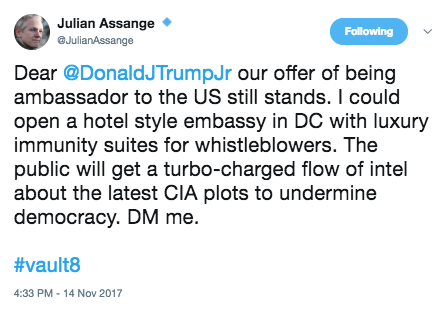

That means the extradition request came amid an effort by Ecuador to grant him diplomatic status after which he might be exfiltrated to Ecuador or Russia; the extradition request came the day after the UK denied him diplomatic status.

Ecuador last Dec. 19 approved a “special designation in favor of Mr. Julian Assange so that he can carry out functions at the Ecuadorean Embassy in Russia,” according to the letter written to opposition legislator Paola Vintimilla.

“Special designation” refers to the Ecuadorean president’s right to name political allies to a fixed number of diplomatic posts even if they are not career diplomats.

But Britain’s Foreign Office in a Dec. 21 note said it did not accept Assange as a diplomat and that it did not “consider that Mr. Assange enjoys any type of privileges and immunities under the Vienna Convention,” reads the letter, citing a British diplomatic note.

Both events came in the wake of the revocation of Joshua Schulte’s bail after he got caught using Tor, in violation of his bail conditions. And the events came days before Donald Trump’s longtime political advisor Roger Stone told Randy Credico he was about to orchestrate a blanket pardon for Assange.

In early January, Roger Stone, the longtime Republican operative and adviser to Donald Trump, sent a text message to an associate stating that he was actively seeking a presidential pardon for WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange—and felt optimistic about his chances. “I am working with others to get JA a blanket pardon,” Stone wrote, in a January 6 exchange of text messages obtained by Mother Jones. “It’s very real and very possible. Don’t fuck it up.” Thirty-five minutes later, Stone added, “Something very big about to go down.”

The indictment used to submit an extradition request yesterday was approved by an EDVA grand jury on March 6, 2018, 13 months ago and just a few months after the extradition request.

That means the indictment has been sitting there at EDVA since a few days before Mueller obtained warrants to obtain the contents of five AT&T cell phones, one of which I suspect belongs to Roger Stone (see this post for a timeline of the investigation into Stone). The indictment has been sitting there since a few weeks before Ecuador first limited visitors for Julian Assange last March. It has been sitting there for three months before the government finally indicted Joshua Schulte, in June 2018, for the leak of Vault 7 files they had been pursuing for over a year (see this post for a timeline of the investigation into Schulte). It was sitting there when, in July, Mueller rolled out an indictment referring to WikiLeaks as an unindicted co-conspirator with GRU on the 2016 election hacks, without charging the organization. It was also sitting there last July when David House testified about publicizing Chelsea Manning’s case to the grand jury under a grant of immunity. It was sitting there when Schulte got videotaped attempting to leak classified information from jail, making any prosecution far easier from a classified information standpoint; that happened right around the time Ecuador ratcheted up the restrictions on Assange. It had been sitting there for 10 months by the time Mueller indicted Roger Stone for lying about optimizing the WikiLeaks release of documents stolen by Russia, again while naming but not charging WikiLeaks. It had been sitting there for 11 months when Chelsea Manning first got a subpoena to testify before an EDVA grand jury, and a full year before she went public with her subpoena. It had been sitting there for over a year when Mueller announced he was finishing on March 22; likewise it has been sitting there ever since Bill Barr announced Trump’s team hadn’t coordinated with the Russian government but remained silent about coordination with WikiLeaks.

In short, the indictment has been sitting there for quite some time and the extradition warrant even longer, even as several different more recent investigations appear to be relentlessly moving closer to WikiLeaks. It has been sealed, assuming it’s the same as the complaint the existence of which was accidentally revealed late last year because, “due to the sophistication of the defendant and the publicity surrounding the case, no other procedure is likely to keep confidential the fact that Assange has been charged.”

There’s a somewhat obvious reason why it got indicted when it did. As WaPo and others have pointed out, the eight year statute of limitations on the CFAA charges in the indictment would have run last year on March 7, 2018.

But that doesn’t explain why DOJ decided to charge Assange in this case, when Assange’s actions with Vault 7 appear far more egregious, or why the indictment is just being unsealed now. And it doesn’t explain why it got released — without any superseding allegations — now, even while WaPo and CNN report more charges against Assange are coming.

Here’s what I suspect DOJ is trying to do with this indictment.

The discussion of cracking the password takes place as Manning runs out of files to share

First, consider these details about the indictment. As I noted earlier, the overt act it charges as a conspiracy is an agreement to crack a password.

On or about March 8, 2010, Assange agreed to assist Manning in cracking a password stored on United States Department of Defense computers connected to the Secret Internet Protocol Network, a United States government network used for classified documents and communications, as designated according to Executive Order No. 13526 or its predecessor orders.

[snip]

The portion of the password Manning gave to Assange to crack was stored as a “hash value” in a computer file that was accessible only by users with administrative-level privileges. Manning did not have administrative-level privileges, and used special software, namely a Linux operating system, to access the computer file and obtain the portion of the password provided to Assange.

Cracking the password would have allowed Manning to log onto the computers under a username that did not belong to her. Such a measure would have made it more difficult for investigators to identify Manning as the source of disclosures of classified information.

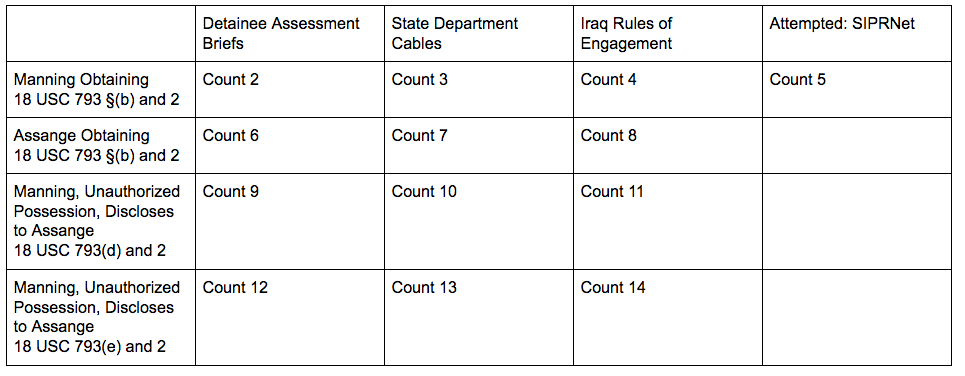

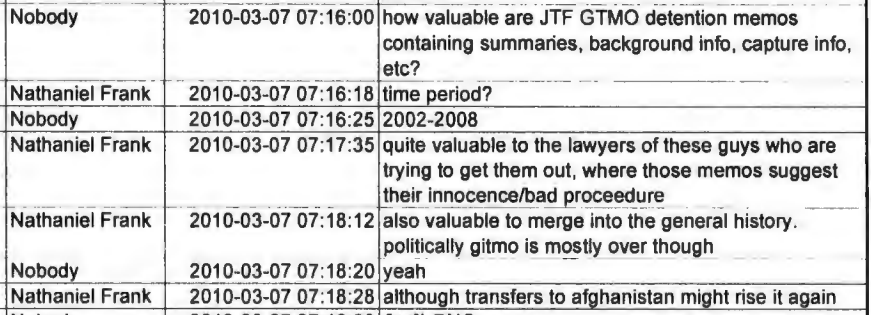

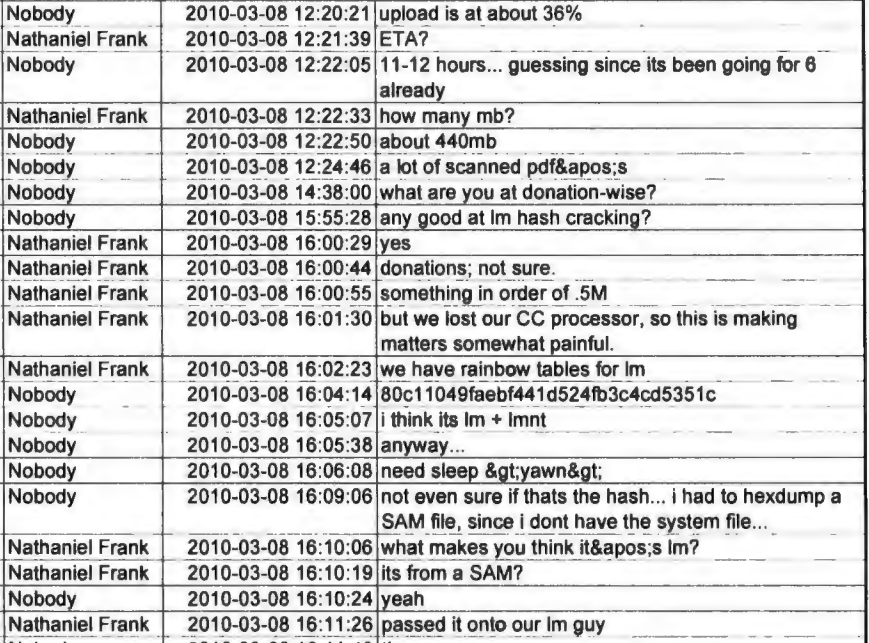

More specifically, the overt act relates to some exchanges revealed in chat logs that have long been public, dating to March 2010 (see this post for a timeline of some related activities from this period, but not this chat; this post describes a chronology of Manning’s alleged leaks). This is a period when Manning had already leaked things to WikiLeaks, including the Collateral Murder video they’re in the process of editing during the conversation and the Iraq and Afghan war logs that were apparently a focus of the David House grand jury testimony.

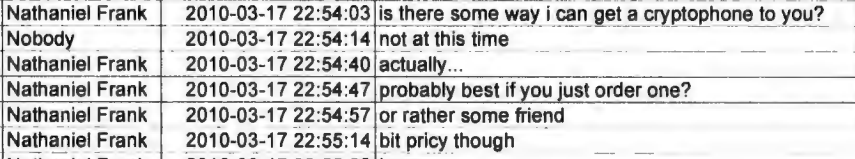

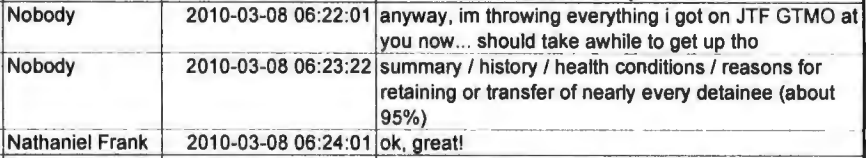

In the logs, Manning asks whether WikiLeaks wants Gitmo detainee files (a file that, in my opinion, was one of the most valuable leaked by Manning). Assange isn’t actually all that excited because “gitmo is mostly over,” but suggests the files may be useful to defense attorneys (they were! to some of the same defense attorneys defending Assange now!) or if Afghanistan heats up.

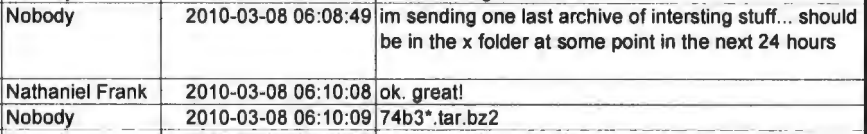

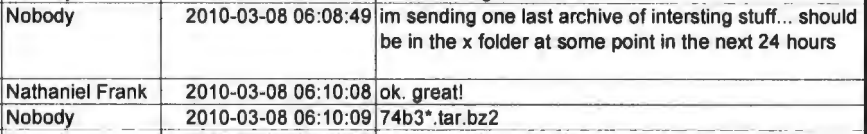

Manning says she’s loading one more archive of interesting stuff.

This appears to be the Gitmo files.

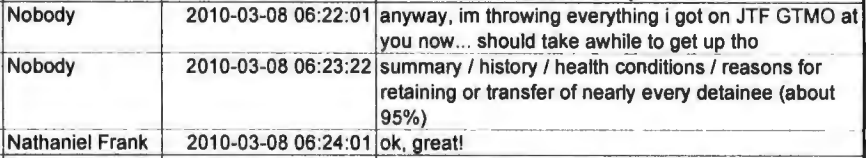

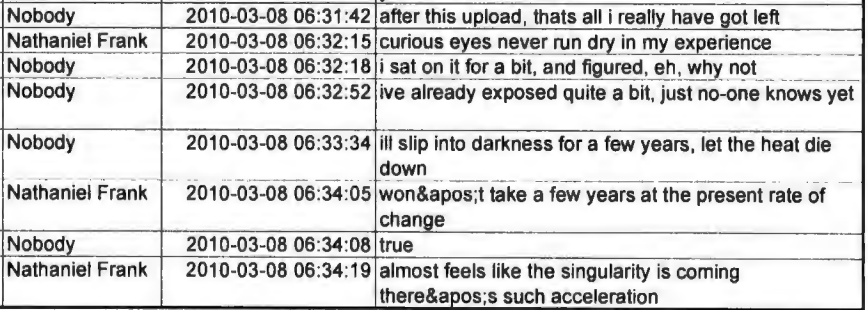

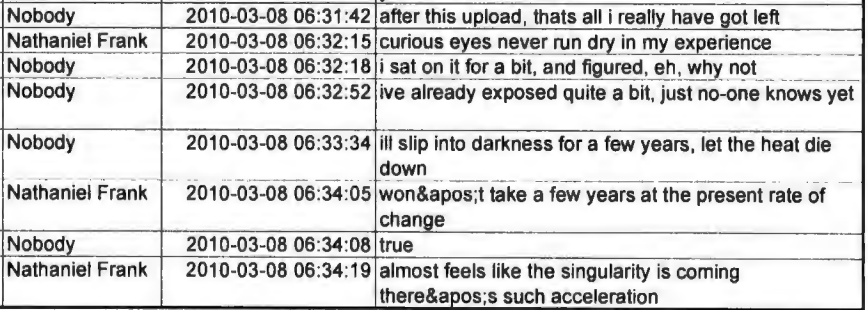

Manning explicitly says that’s all she’s got, and then talks about taking some years off to let heat die down, even while gushing about the current rate of change.

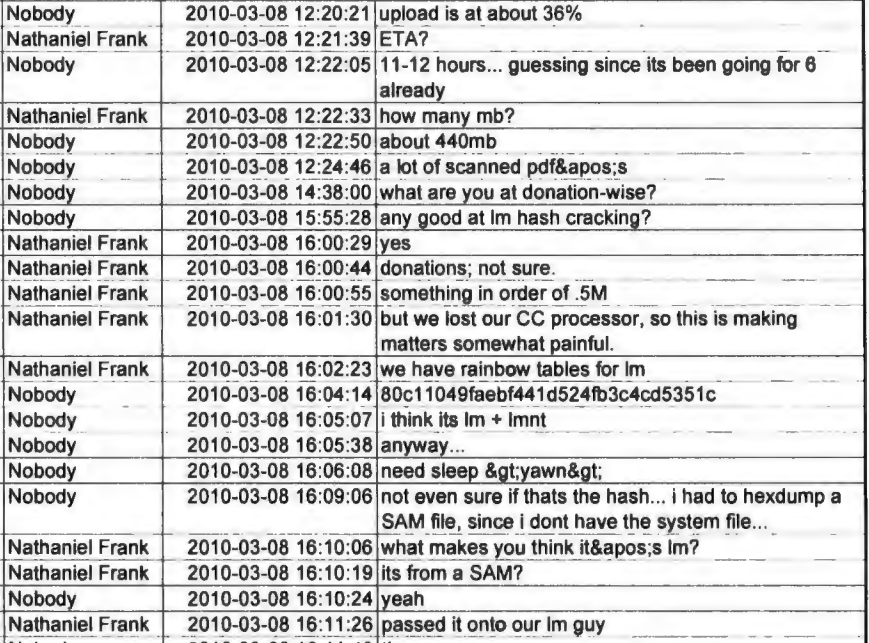

Some hours later, amid a discussion about the status of the upload of the Gitmo files that are supposed to be the last file she’s got, Manning then asks Assange if he’s any good at cracking passwords.

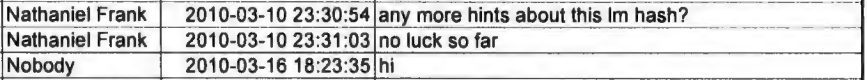

He says he has, “passed it onto our lm guy.”

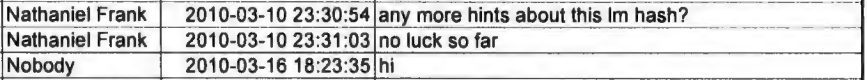

Two days later Assange asks for more information on the hash, stating (as the indictment notes) that he’s had no luck cracking it so far. Then there’s a six day break in the chat logs, at least as presented.

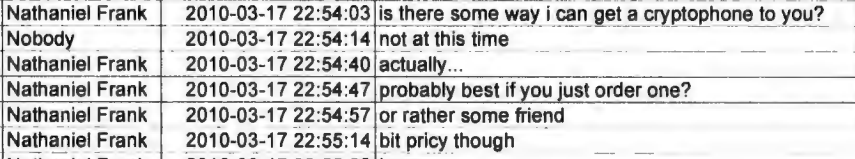

The next day Assange floats getting Manning a crypto phone but then thinks better of it.

These chat logs end the next day, March 18, 2010. As the indictment notes, however, it’s not until ten days later, on March 28, 2010, that Manning starts downloading the State cable files.

Following this, between March 28, 2010, and April 9, 2010, Manning used a United States Department of Defense computer to download the U.S. Department of State cables that WikiLeaks later released publicly.

It’s unclear whether Assange ever cracked the password — but the chat log suggests he involved another person in the conspiracy

Most people have assumed, given what the indictment lays out, that Assange never succeeded in cracking the password. I have no idea whether he did or not, but I’m seeing people base that conclusion on several faulty assumptions. (Update: HackerFantastic notes that Assange couldn’t have broken this password, but goes on to describe how using other code it might be possible; that’s interesting because Manning was alleged to have added additional software onto the network after the initial Linux device, on May 4, 2010.)

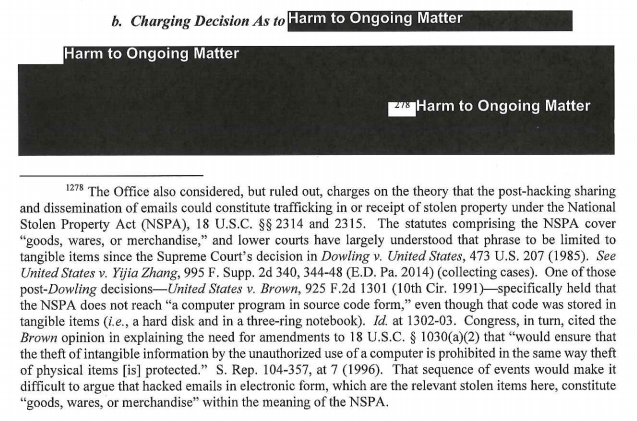

First, some people assume that if Assange had succeeded in cracking the password, the indictment would say so. I’m not so sure. The indictment only needs to allege that Assange and Manning entered into a conspiracy — which the indictment deems a password cracking conspiracy — and took an overt act, whether or not the conspiracy itself was successful. The government suggests that Assange’s comment that he’s had “no luck so far” shows that he has taken an overt act, trying to crack it. Nothing else is required for the purposes of the indictment.

Further, several things about the chat log, as received, suggests there may be more going on in the background. There’s the six day gap after that conversation. There’s the contemplation of getting Manning a crypto phone. And then the chat logs as the government has chosen to release them end, though as the government notes, ten days after they end, Manning starts downloading the State cables.

But the record at least suggests that this conspiracy involves at least one more person, the “lm guy.” Maybe Assange was just falsely claiming to have a guy who focused on cracking certain kinds of hashes. Or maybe the government knows who he is.

The reference to him, however, suggests that there’s at least one more person in this conspiracy. The indictment notes there are “other co-conspirators known and unknown to the Grand Jury,” which is the norm for conspiracy indictments. But there are no other details of who else might be included.

Yes, this particular conspiracy is incredibly narrowly conceived, focused on just that password decryption. But there’s also the “Manner and Means of the Conspiracy” language that has (rightly) alarmed journalists so much, describing the goal of acquiring and sharing classified information that WikiLeaks could disseminate, and describing the operational security (Jabber and deleted chat logs) and inducement to accomplish that goal.

In other words, this indictment seems to be both an incredibly narrow charge, focused on a few Jabber conversations between Assange and Manning, and a much larger conspiracy in which Assange and other unnamed co-conspirators help her acquire and transmit classified documents about the US.

The logistics of the conspiracy prosecution(s)

Which brings me back to how this indictment might fit in amidst several larger, parallel efforts to prosecute WikiLeaks in the last 16 months.

This indictment may be the formalization of a complaint used as the basis for what seems to be a hastily drawn extradition request in December 2017, at a time when Ecuador and Russia were attempting to spring Assange, possibly in the wake of the government’s move to detain Schulte.

The indictment does not allege the full Cablegate conspiracy. David House testified months ago. And the government currently has Manning in jail in an attempt to coerce her to cooperate. That coercive force, by the way, may be the point of referencing the Espionage Act in the indictment: to add teeth to the renewed legal jeopardy that Manning might face if she doesn’t cooperate.

But what the indictment does — and did do, yesterday — is serve as the basis to get Assange booted from the embassy and moved into British custody, kicking off formal extradition proceedings.

As a number of outlets have suggested, any extradition process may take a while. Although two things could dramatically abbreviate it. First, Sweden could file its own extradition on the single remaining rape charge against Assange, which might get priority over the US request. Ironically, that might be Assange’s best bet to stay out of US custody for the longest possible time. Alternately, Assange could simply not contest extradition to the US, which would leave him charged in this bare bones indictment that even Orin Kerr suggests is a fairly aggressive charging of CFAA.

Barring either of those things happening, however, the US government now has one suspect in any conspiracy it wants to charge in the custody of a friendly country. It has accomplished that with entirely unclassified allegations, which means any other suspects won’t know anything more than they knew on Wednesday. Anything else it wants to charge — or any other moving parts it needs to pursue — it can now do without worrying too much that Assange will be put in the “boot” of a Russian diplomatic vehicle to be exfiltrated to Russia.

It has between now and at least May 2 — when Assange has his next hearing — to add any additional charges against Assange, while still having them charged under the Rule of Specialty before any possible extradition. It has maybe a month left on the Mueller grand jury.

Meanwhile, several things have happened recently.

First, in recent weeks two things have happened in the Schulte case. His lawyers made yet another bid to get the warrants that justified the initial searches excluded from the protective order. Schulte and his lawyers have been complaining about these warrants from the start, and Schulte’s public comments or leaks about them are part of what got him charged with violating his protective order. From description, it sounds like FBI was parallel constructing other information tying him to the Vault 7 leaks, and fucked up royally in doing so, introducing errors in the process (though the Hal Martin case makes me wonder whether the errors aren’t still more egregious). The government objected to this request, arguing that the warrants would disclose how the CIA stored its hacking documents and asserting that the investigation is definitely ongoing.

The Search Warrant Materials discuss, among other things, the way that the U.S. Intelligence Agency maintained a classified computer system that was integral to the Agency’s intelligence-gathering mission. Broadly disseminating that information would permit a host of potentially hostile actors to glean valuable intelligence about the way the U.S. Intelligence Agency maintained its computer systems or its security protocols, which would harm national security.

[snip]

The defendant’s abbreviated argument for de-designating the Search Warrant Materials is speculative, conclusory, and misguided. First, the defendant claims that the “time for investigation is long gone.” (Def. Let. at 1). The defendant is neither in a position to judge nor the arbiter of when it is appropriate for the Government to end its investigation into one of the largest-ever illegal disclosures of classified information. Simply put, while details are not appropriate for discussion in a public letter, the Government confirms that its investigation is not done and can supply the Court with additional information on an ex parte basis if the Court wishes.

Meanwhile, the government suggested severing the most recent charges — in which it has video surveillance showing Schulte leaking classified or protected information — from the underlying child porn and Vault 7 leaks.

As the Court is aware, trial in this matter is currently set for April 8, 2019. (See Minute Entry for August 8, 2018 Conference). To afford the parties sufficient time to prepare the necessary pretrial motions, including suppression motions and motions pursuant to the Classified Information Procedures Act (“CIPA”), the parties respectfully request that the Court adjourn the trial until November 4, 2019. The parties are also discussing a potential agreement concerning severance, as well as the order of the potentially severed trials. The parties will update the Court on severance and a pretrial motion schedule at or before the conference scheduled for April 10, 2019.

The defense didn’t weigh in on this plan, which (it would seem) would go a long way to eliminating the government’s parallel construction problem. They were supposed to talk about the severance issue in a hearing Monday, but it sounds like the only thing that got discussed was CIA’s refusal to comply with discovery. My guess is that Schulte will try to get those initial warrants and any fruit of them thrown out, and if that doesn’t work then maybe plead down to prevent a life sentence.

Meanwhile, Ecuador has taken steps to roll up people it claims have ties to Assange.

Tuesday, it fired a staffer in the embassy who had been extremely close to Assange (which may be how he learned about the plans to arrest him last week). Then, yesterday, Ecuador detained Swedish coder Ola Bini, alleging he was involved in some of the hacking they’ve accused Assange of. They also claim to know of two Russian hackers involved.

I have no idea if these developments are just Ecuador trying to cover-up corruption or real ties to WikiLeaks or perhaps something in between. There are no trustworthy actors here.

But — as William Arkin also notes — there’s an effort to test whether WikiLeaks has been at the front end of many of these leaks. Aside from WikiLeaks’ reported source for its Saudi Leaks files from Russia, Arkin focuses less on the reasons there are real questions about WikiLeaks’ relationship with Russia. I think we honestly won’t know which of the untrustworthy sides is being more trustworthy until we see the evidence.

Whichever it is, it seems that DOJ is poised to start building out whatever it can on at least one conspiracy indictment against WikiLeaks. The indictment and its implementation yesterday seems primarily to have served as a way to lock down one part — the most volatile one — of the equation. What comes next may assuage concerns about the thinness of this indictment or it may reveal something far more systematic.

In the meantime, Assange is represented by some great lawyers, both in the UK and here. Which at least increases the chances any larger claims DOJ plans to roll out will be tested aggressively.

As I disclosed last July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.