Methinks Joshua Schulte Doth Protest Too Much over Anonymous

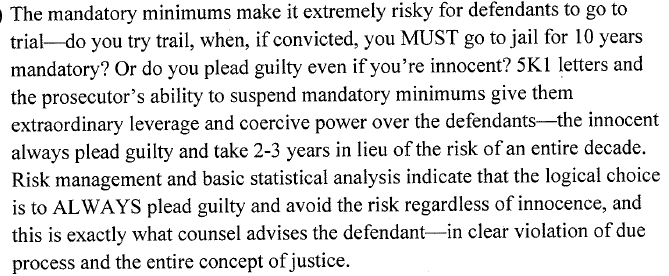

Accused Vault 7 leaker Joshua Schulte — whose trial starts Monday — and the government are having a fight over Paul Rosenzweig’s expert witness testimony again (see this post for the most comprehensive coverage of this dispute). Rosenzweig submitted the Powerpoint he plans to use at trial. Schulte raised objections to the Powerpoint as a whole and to specific slides on it. And the government responded, offering to make some modifications.

The general complaint from Schulte is that the government is using Rosenzweig to introduce otherwise inadmissible hearsay. In one case, the government has agreed to withdraw the claim (a quote from Fred Kaplan, who in my opinion is not particularly reliable with respect to WikiLeaks in any case). The government makes two responses of particular interest. First, that experts are allowed to draw on periodicals to make their conclusions.

Moreover, the defendant’s objection to the introduction of statements from respected news publications ignores that the Rules of Evidence expressly provide for the introduction of such material. Federal Rule of Evidence 803(18) expressly permits the recitation of “[a] statement contained in a . . . periodical . . . if . . . the statement is . . . relied on by the expert on direct examination; and . . . the publication is established as a reliable authority by the expert’s admission or testimony, by another expert’s testimony, or by judicial notice.”

After pulling the Kaplan quote, there’s not really much left in the slide deck that quotes journalistic sources, aside from direct quotes about the diplomatic backlash to the State cables. But what the government doesn’t say is that WikiLeaks presents itself as a respected news publication, which if they truly believe is true should allow introducing the WikiLeaks material as such.

But the government wants to prevent that from coming into evidence (even though Schulte warned that calling Rosenzweig would invite it). Indeed, rather than including material from the About page that Schulte would like to include that makes that point,

The excerpts from the WikiLeaks website are taken out of context. If the government is permitted to introduce two sentences from the lengthy “about” page on WikiLeaks.org, the defense would be entitled to introduce other portions of that page, including that WikiLeaks is a “multi-national media organization and associated library,” that it has “contractual relationships” with more than 100 major media organizations, and that it has won numerous media awards. See https://wikileaks.org/What-is-WikiLeaks.html.

The government has offered to pull this slide:

Rather than conceding (or even mentioning) WikiLeaks’ claim to be a respected media outlet, the government says it can introduce the vast majority of the clips from WikiLeaks’ site because they are not assertions at all.

Indeed, other than WikiLeaks’ statements regarding the content of the Vault 7 leaks, the particular statements from WikiLeaks and Assange about which Mr. Rosenzweig will testify are not “statements” or “assertions” such that the rule against hearsay is even applicable.

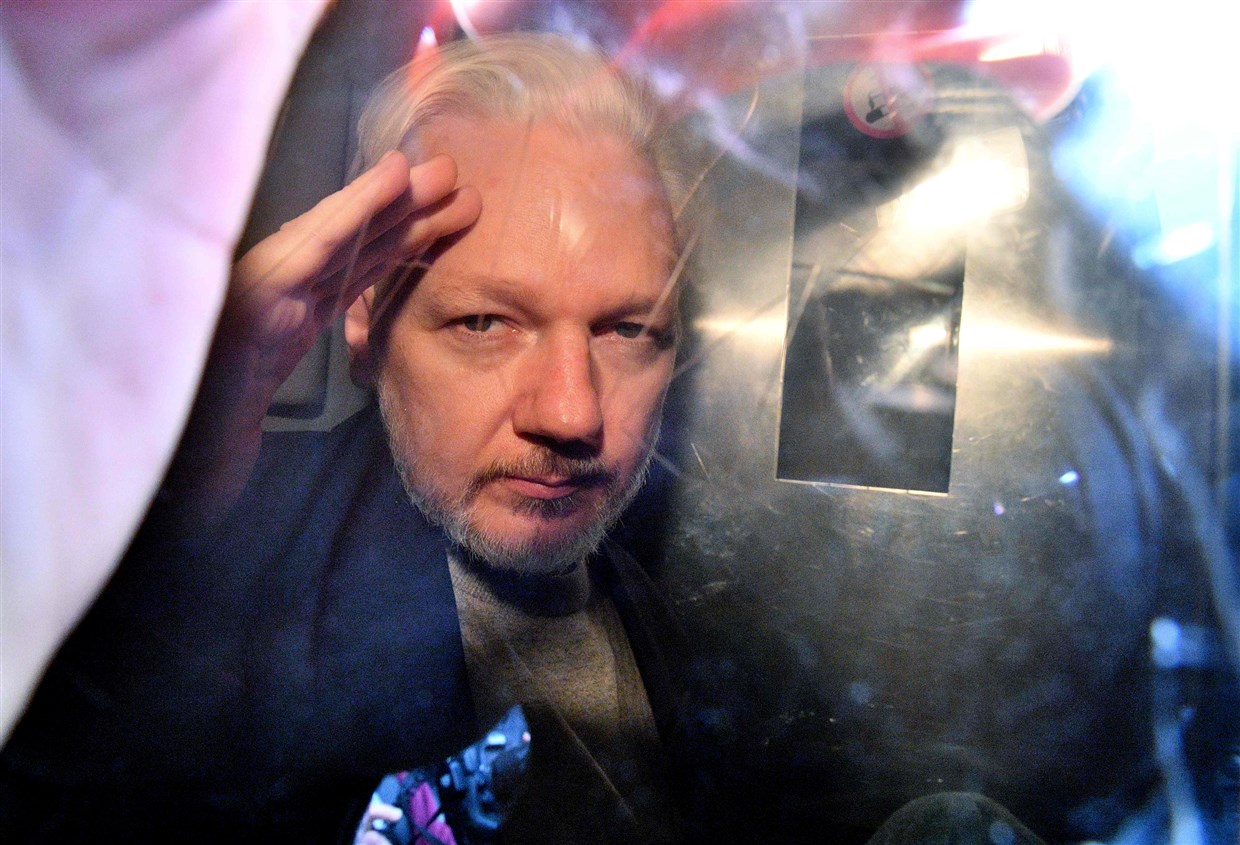

That’s true. Some of what Rosenzweig plans to submit includes the pre-release hype WikiLeaks gave the Vault 7 release, including the release purporting to show the US had infiltrated French political parties (which it claimed provided justification for the Vault 7 release) and slides emphasizing the spookiness of the release, including this one invoking Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden in the same breath as Julian Assange.

Other slides capture the instructions WikiLeaks gives to leakers, including to contact WikiLeaks if you have very large submissions (as this was) and to format and dispose of hard drives.

The government will claim Schulte followed some — but not all — of these instructions, in part because he couldn’t dispose of his CIA workstation, and in part because he kept the hard drives and a thumb drive he used to exfiltrate the files.

Mind you, WikiLeaks didn’t warn leakers not to Google everything they were doing as they did it, which is the really damning evidence against Schulte.

In any case, I can’t help but imagine we’ll be seeing this very same slide deck in a trial in EDVA (if Assange is ever extradited), as it shows a continuation of the kinds of activities charged in the existing Assange indictment. Assange’s extradition hearing has been split into two, with the second starting in May, so the government would have plenty of time to add such charges after this trial (which may last a month).

In addition to Rosenzweig’s refusal to include WikiLeaks’ awards (which I would imagine Schulte will bring out on cross in any case, though I honestly wonder why they didn’t bring in their own expert to present such material), one Schulte claim that absolutely has merit is that Rosenzweig should not use the WikiLeaks logo on all these slides.

Each page of the power point has the WikiLeaks logo and name from the WikiLeaks website as if the power point document itself was created by WikiLeaks. This creates a misleading impression and should be removed.

Schulte doesn’t lay out what misleading impression the logo provides, but I would argue it suggests that WikiLeaks endorses some of the content in the slide deck, pertaining to damage or the characterization of certain leaks. The government says this misleading impression can be avoided with an instruction.

With respect to the inclusion of the WikiLeaks logo on the relevant pages of the Demonstrative, WikiLeaks is the subject of his testimony, and it is reasonable to include it as a header. To avoid any confusion, the Government will elicit from Mr. Rosenzweig that the Demonstrative as a whole was prepared as a demonstrative aid for his testimony and was not produced by WikiLeaks.

I vehemently disagree with this stance. Over half of people are visual learners (indeed, the government will rely on visual reenactments to show how they claim Schulte stole the files). The logo on this slide deck ascribes to WikiLeaks things that they would strongly dispute. Particularly given that Rosenzweig is claiming there are three official WikiLeaks channels — the site, the WikiLeaks Twitter account, and Assange’s Twitter account — it is imperative that he differentiate in his presentation between what is official and what is his own analysis.

All of which is to say that, as predicted, calling Rosenzweig will invite a dispute over what kind of organization WikiLeaks really is (which is probably the point).

All that said, I’m frankly stunned that, amidst all the other slides in this presentation — including the one showing convicted leaker Chelsea Manning (whose leaks, the government will show, Schulte viewed as damaging in real time) and admitted leaker Edward Snowden (whom the government will show Schulte was Googling at a key time in August as he was also Googling WikiLeaks for almost the first time) — Schulte objects, again, to the invocation of Anonymous in this slide.

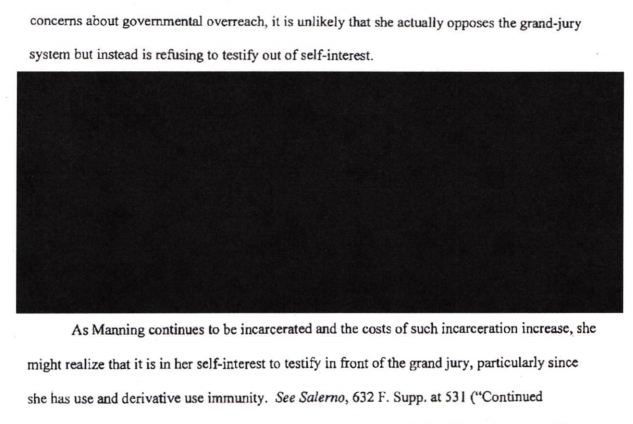

Having not objected that the government will raise Chelsea Manning and not objected that the government will raise Edward Snowden, Schulte is objecting that they’re raising Jeremy Hammond — like Manning, a confessed WikiLeaks source — and a 2010 operation to punish Paypal and others for blacklisting WikiLeaks.

We renew our objections to references to Anonymous, which are irrelevant and prejudicial.

As I have laid out, the way in which Schulte himself adopted the identity of Anonymous as part of his effort to leak to the WaPo from jail links together the three main pieces of evidence of that — his Signal texts with Shane Harris, his ProtonMail account in the name of Anonymous, and his prison notebooks. Schulte’s the one who claimed to be Anonymous, whether or not it’s true (and given the ethics the group adopts about membership, by claiming to be a member he basically is one). Anonymous’ tie to WikiLeaks is clearly admissible evidence based on Schulte’s own actions.

Schulte deems the invocation of Anonymous to suggest “concerted activity” that is more disturbing than simply stealing CIA’s hacking tools and leaking them to WikiLeaks in an effort to burn CIA to the ground out of spite for being made to sit in what Schulte considered an “intern desk” rather than a “prestigious desk with a window,” which is the motive the government says it will present.

The evidence of claimed participation in a shadowy, underground group infamous for cyber-attacks and dumping on WikiLeaks is unduly prejudicial as it suggests concerted activity of a type even more disturbing than what is charged.

The evidence suggests that Schulte adopted at least three personalities to leak from jail, deliberately attempting to present the illusion of concerted activity. Given the concerted concern about Anonymous amid all the equally damning references, perhaps some of Schulte’s imaginary friends aren’t actually imaginary?

As I disclosed in 2018, I provided information to the FBI in 2017. The government recently stated publicly that matters on which I shared information are related to Schulte. Aside from two press inquiries, I have not spoken with the government about Schulte.