As Democrats Entertain a Ukraine-Only Impeachment, Jack Goldsmith Lays Out Import of Impeaching for Clemency Abuse

As June Bug the Terrorist Foster Dog and I drove the last leg of our epic road trip over the last few days, I listened to Jack Goldsmith’s book on his stepfather, Chuckie O’Brien, In Hoffa’s Shadow: A Stepfather, a Disappearance in Detroit, and My Search for the Truth.

It’s a fascinating book I’m pondering how to write about: Imagine a book written by a top surveillance lawyer describing how he learned things his beloved stepfather was lying about by reading old FBI transcripts of wiretaps targeted at top mobsters.

The entire point of the book is to exonerate O’Brien of any role in Jimmy Hoffa’s murder, and it fairly convincingly does that. As Goldsmith describes, the FBI admitted privately to him that they belatedly realized his father couldn’t have had a role in Hoffa’s disappearance, but because the FBI is the FBI, they refused to state that in an official letter (though it was Barb McQuade, then as Detroit’s US Attorney, who made the final call).

But in Goldsmith’s effort to exonerate his step-father on the Hoffa murder, he implicates him in a shit-ton of other crimes … including being the bagman for a $1 million bribe to Richard Nixon so he would commute Hoffa’s sentence for jury tampering (which Chuckie was also a key player in). Here’s how Goldsmith describes O’Brien’s claims about the payoff.

Chuckie nonetheless insists there was a payoff. And he says he was the delivery boy.

Chuckie told me that in early December 1971, he received a telephone call in Detroit from Fitzsimmons’s secretary, Annie. “Mr. Fitzsimmons would like to see you,” she said. Chuckie got on the next plane, flew to Washington, and went straight to Hoffa’s former office at the foot of Capitol Hill. After small talk, Fitzsimmons got to the point. “He’s coming home, and it’s going to cost this much,” Fitzsimmons whispered to Chuckie, raising his right index finger to indicate $1 million. “There will be a package here tomorrow that I want you to pick up and deliver.”

The following afternoon, Annie called Chuckie, who was staying at a hotel adjacent to the Teamsters headquarters near the Capitol building. “Mr. Fitzsimmons asked me to tell you that you left your briefcase in his office,” she said. Chuckie had not left anything in Fitzsimmons’s office, but he quickly went there. Fitzsimmons was not around, but Annie pointed Chuckie to a leather litigation bag next to Fitzsimmons’s desk—a “big, heavy old-fashioned briefcase,” as Chuckie described it. Chuckie picked up the bag, and Annie handed him an envelope. Inside the envelope was a piece of paper with “Madison Hotel, 7 p.m.” and a room number written on it.

It was about 5:00 p.m., and Chuckie took the bag to his hotel room. He had delivered dozens of packages during the past two decades, no questions asked, mostly for Hoffa, sometimes for Giacalone, and very occasionally for Fitzsimmons. But this time was different. Chuckie knew of the strain between Fitzsimmons and Hoffa. He wasn’t sure what game Fitzsimmons was playing, especially since Hoffa had not at this point discussed a payoff with him. Chuckie was anxious about what he was getting into. And so he did something he had never done before: he opened the bag.

“I wanted to see what was in the briefcase,” Chuckie told me. “I didn’t trust these motherfuckers. I needed to look; it could have been ten pounds of cocaine in there and the next thing I know a guy is putting a handcuff on me.”

What Chuckie saw was neatly stacked and tightly wrapped piles of one-hundred-dollar bills. He closed the bag without counting the money.

The Madison Hotel, where Chuckie was supposed to deliver the bag, was two miles away, six blocks north of the White House. It “was a very famous hotel” in the early seventies, a place where “political big wheels” and “foreign dignitaries” stayed, Chuckie told me. At about 6:45 p.m., Chuckie took a taxi to the Madison, went to the designated floor, walked to the room (he doesn’t remember the number), and knocked on the door. A man opened the door from darkness. Chuckie stepped in one or two feet. He sensed that the room was a suite, but could not tell for sure.

“Here it is,” Chuckie said, and handed over the bag.

“Thank you,” said the man. Chuckie turned and left. That was it. The whole transaction, from the time he left his hotel to the delivery on the top floor of the Madison, took less than twenty minutes. The actual drop was over in seconds.

If O’Brien is telling the truth, it means that in addition to locking in Teamster support for 1972, Nixon got a chunk of money for the election (just as Trump just hit up Wayne LaPierre for fundraising support in exchange for killing gun control).

Goldsmith’s step-father claims that the money for the payoff came directly from Hoffa — but he either didn’t know or wouldn’t say whom he delivered it to.

“Where did the money come from?” I asked. “From the Old Man,” Chuckie answered. “Through Allen Dorfman. It was the Old Man’s money. Dorfman had a lot of his money. Fitz wouldn’t give you a dime if you were dying.”

[snip]

“Did Fitz tell you who you were delivering the bag to?” I asked. “No. I took the fucking briefcase to where it’s supposed to go, I never asked any questions. You never ask, Jack.”

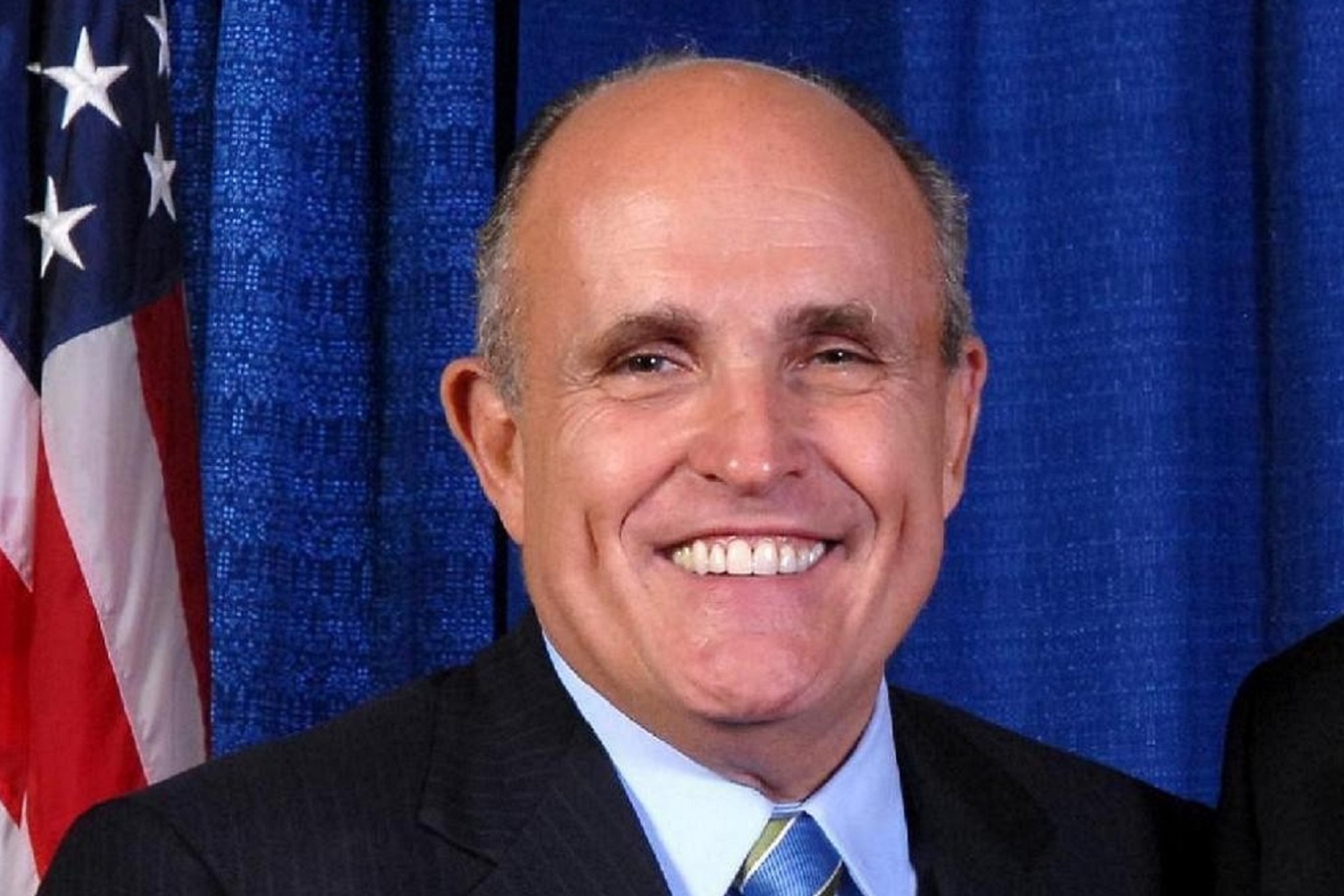

This is something that John Mitchell lied about to prosecutors, just as the stories of Rudy Giuliani and Jay Sekulow regarding the pardons they’ve negotiated with Russian investigation witnesses don’t hold up.

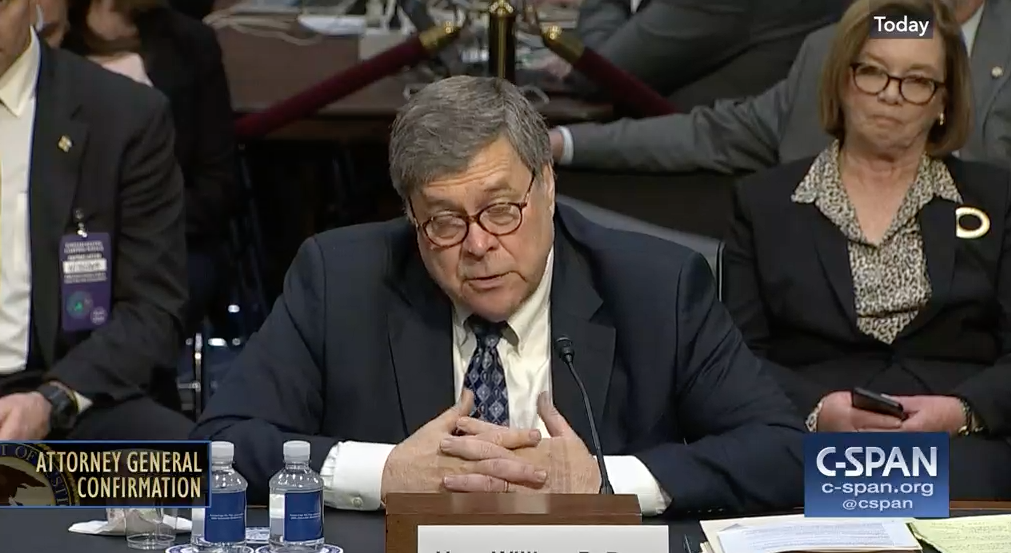

Since that time, presidential abuses of pardons have only gotten worse. Say what you will about the Marc Rich pardon (and I agree it was ridiculous), both Poppy Bush (Cap Weinberger) and W (Scooter Libby) provided clemency to witnesses to silence them about actions of the Bush men. Bill Barr was a key player in the Poppy pardons, and he seems all too willing to repeat the favor for Trump.

Until Congress makes reining in the abuse of executive clemency a priority, the claim that no one is above the law will be a pathetic joke. Plus, there are at least allegations that Trump’s effort to dig up Ukrainian dirt stemmed from an effort to make pardoning Paul Manafort easier. And the Ukraine corruption involves someone — Rudy — who was intimately involving in bribing witnesses with pardons in the past.

More generally, any decision to narrowly craft impeachment would be catastrophically stupid, not least because other impeachable acts — such as Trump’s treatment of migrants — will be far more motivating to Democratic voters than Ukraine. But to leave off Trump’s abuse of the pardon power would be a historic failure.