I want to start this post by reiterating that I agree with the conclusion of the DOJ IG Report on Carter Page that there were significant errors with the Carter Page FISA applications, especially the reauthorizations. I think the Report provides a lot of valuable detail about the Crossfire Hurricane investigation, though not necessarily the details about the FISA process or keeping the country safe that policy makers need (which I’ll return to). I think its recommendations are worthwhile but insufficient to fix the problems identified by the review.

So I find the IG Report an important review of the FISA process.

But it is also the case that the IG Report commits precisely the kinds of errors it finds inexcusable in the FBI.

As I lay out here, the major problems with the Carter Page FISA applications all amount to FBI not providing (first) DOJ’s Office of Intelligence and then the FISA Court critical information (regarding Page’s 2009-2013 ties to the CIA, information that undermine claims that Christopher Steele and the dossier were reliable, and other information — some that contradicted the dossier — that the IG Report deems exculpatory). The IG Report also found 17 items over the course of four applications that did not meet the Woods procedure requirement of being backed by documentation in the file (this table lays out that information, along with all the derogatory information in Page’s applications). Some of these Woods procedure problems reflect bureaucratic sloppiness in the procedure that’s supposed to guarantee reliability on FISA issues; some are more significant errors.

Given those errors (again, errors I significantly agree are shown in the Report), then, DOJ IG ought to make damn sure they don’t commit the same kinds of errors they deem serious enough to refer the entire FBI chain of command for discipline up to and including firing). But they did.

Errors identified on publication

Let’s start with the corrections made to the report, first on December 11 and then on December 20. On December 11, there were three changes, one of which reflected prior declassification of the dates of the FISA orders targeting Page and additional declassification regarding Sergei Millian, The other two changes are corrections of inaccurate claims made in the first release of the report.

The first involves an utterly central part of DOJ IG’s inquiry: at what point in time the FBI got informants to interview Carter Page, Sam Clovis, and George Papadopoulos. When the report was initially released, it falsely claimed that Page and Papadopoulos had been targeted with informants before FBI had formally opened its investigation on July 31, 2016.

On pages iv, xvi, 400, and 407, we changed the phrase “before and after” to “both during and after the time.” In all instances, the phrase appears in connection to the time period during which we found that the Crossfire Hurricane team used Confidential Human Sources (CHSs) to interact and consensually record conversations with Page and Papadopoulos. The corrected information appearing in this updated report reflects the accurate information concerning these time periods that previously appeared, and still appears, on pages 305 and 313 (e.g., the statement on page 305 that “the Crossfire Hurricane team tasked CHSs to interact with Page and Papadopoulos both during the time Page and Papadopoulos were advisors to the Trump campaign, and after Page and Papadopoulos were no longer affiliated with the Trump campaign”).

Based in part on the fact that Stefan Halper met Carter Page before he was formally tasked as an informant to collect information from him, and in part on George Papadopoulos’ paranoid rants, the frothy right had been accusing the FBI of using informants before the investigation was opened. And when then Report was initially released, it stated that that had, in fact occurred, even though the narrative in the Report made it clear that that did not happen (though it did show that the FBI had used informants before either Page or Papadopoulos had been kicked off the campaign). So the initial report falsely claimed the Report confirmed a frothy right conspiracy, but within days DOJ IG corrected that false claim. In other words, before subjected to the scrutiny of public review, the Report made a false claim about a core topic of its investigation.

Another of the corrections made on December 11 involves information about what an interview of Christopher Steele’s Sub-Source said when the FBI interviewed him or her to assess the credibility of Steele’s reporting. The report originally stated that the Sub-Source affirmatively stated he or she had no discussion with Steele about WikiLeaks, but the revised Report instead stated that the Sub-Source did not recall having such a discussion.

On pages xi, 242, 368, and 370, we changed the phrase “had no discussion” to “did not recall any discussion or mention.” On page 242, we also changed the phrase “made no mention at all of” to “did not recall any discussion or mention of.” On page 370, we also changed the word “assertion” to “statement,” and the words “and Person 1 had no discussion at all regarding WikiLeaks directly contradicted” to “did not recall any discussion or mention of WikiLeaks during the telephone call was inconsistent with.” In all instances, this phrase appears in connection with statements that Steele’s Primary Sub-source made to the FBI during a January 2017 interview about information he provided to Steele that appeared in Steele’s election reports. The corrected information appearing in this updated report reflects the accurate characterization of the Primary Sub-source’s account to the FBI that previously appeared, and still appears, on page 191, stating that “[the Primary Sub-Source] did not recall any discussion or mention of Wiki[L]eaks.”

The distinction is important because Steele claimed — plausibly — that his Sub-Source was shading how much he gave Steele, given how controversial things had become by 2017; Steele also claims to have documentation of what his Sub-Source claimed when.

Whatever the truth on this point, as the correction acknowledges, the FBI’s 302 of the interview uses the “did not recall” language.

[The Primary Sub-source] recalls that this 10-15 minute conversation included a general discussion about Trump and the Kremlin, that there was “communication” between the parties, and that it was an ongoing relationship. (The Primary Sub-source] recalls that the individual believed to be [Source E in Report 95] said that there was “exchange of information” between Trump and the Kremlin, and that there was “nothing bad about it.” [Source E] said that some of this information exchange could be good for Russia, and some could be damaging to Trump, but deniable. The individual said that the Kremlin might be of help to get Trump elected, but [the Primary Sub-source] did not recall any discussion or mention of Wiki[L]eaks. [my emphasis]

In other words, the FBI had an official source for the Sub-Source’s comments, the 302, and the DOJ IG, in its first release, used language that deviated from what the official source said.

This is precisely the kind of error the Report pointed to as Woods procedure violations, such as the FBI’s description of Steele’s reporting as “corroborated and used in criminal proceedings,” when in fact the official document said something different. The Report complains about a similar variance of phrasing in the renewals specifically as they pertain to whether Steele was “high-ranking” or “moderately senior.”

One might excuse the discrepancy because — after all — DOJ IG fixed this language almost as soon as it became public. Except that language pertaining to Steele’s Sub-Source was declassified the night before the Report release, without Steele having had an opportunity to read it. Thus, it is language that appeared in public in violation of DOJ IG’s rules on document reviews, so might have been avoided if it had followed its normal process.

Finally, one of the corrections made on December 20 — fixing of an error of fact regarding the laws that criminalize acting as an agent of a foreign government or principal without registration, but claiming falsely the correction just amounted to adding a reference to the statute in question — would also be the same kind of error that, in the FISA context, would amount to a Woods procedure violation, as it asserts the statute said something it didn’t. Furthermore, a later discussion of the Senate Report on FISA (still) miscites a page discussing FARA, something else that would count as a Woods violation, particularly given that the passage of the Senate Report cited actually undermined the point DOJ IG was trying to make, explaining why Carter Page’s direct ties to known Russian intelligence officers got well past (according to the intent of Congress) the concerns about him being targeted for his First Amendment activities.

Information excluded from the Bruce Ohr discussion

As this post lays out, the IG Report left out at least two key details in its discussion of Bruce Ohr’s communications with Christopher Steele. First, it made no explicit mention of the at least five communications Ohr had with Steele in 2016 prior to their July 30, 2016 brunch meeting. Those contacts were significantly about — but probably not limited to — Oleg Deripaska. Including those contacts would make it clear that the Deripaska reference during their July 30 meeting was a continuation of past discussions, not a new reference tied to the dossier (indeed, nothing that could relate to the Deripaska feud with Paul Manafort showed up in the dossier until October 19, and even then it would have simply been a reference to his Russian ties). Moreover, it would show that all of the contacts between them were a continuation of past information sharing tied to Ohr’s job.

In addition, the IG Report’s discussion of the July 30 meeting omits a Steele mention about Russian doping. That reference, like the multiple references to topics other than Trump in 2017 that the IG Report does acknowledge, make it clear that Ohr and Steele’s communications always included information about their mutual concerns about transnational organized crime.

In other words, DOJ IG twice left out or glossed over details that would have made it clear the Ohr – Steele communications consisted of more than just dirt on Trump, the equivalent of leaving out exculpatory information in the Carter Page application. And the IG Report’s entire presentation of their Deripaska discussions overstate the degree to which those discussions amounted to to information from the dossier (though there are a lot of other problems with the Deripaska-related communications between the two men).

Possible information excluded from the George Papadopoulos transcript

This post shows that, rather than being exculpatory (as the frothy right has long claimed), the substance of Papadopoulos’ conversations with Stefan Halper and another informant were actually fairly damning. The IG Report does not complain that the Carter Page applications leave out the damning details of these interactions (including that both he and Page spoke similarly about an October surprise).

It does, however, complain that the Carter Page applications leave out Papadopoulos’ denials that the campaign was trying to optimize the WikiLeaks releases, even though those denials were internally inconsistent and Papadopoulos explained to the second informant he had made a categorical denial to Halper because he worried Halper might tell the CIA if had made anything but such a categorical denial.

So the IG Report’s case that these denials should have been included in the Carter Page applications is not all that convincing (though it does therefore endorse one of the frothy right complaints that led to this investigation). DOJ lawyer Stu Evans, who generally always supported more disclosure, treated Papadopoulos’ denials like Joseph Mifsud’s later claims not to have had advance knowledge of the email release, as cover stories, which is precisely what the FBI team believed them to be in real time.

As part of its investigation, the FBI interviewed Mifsud in February 2017, after Renewal Application No. 1 was filed but before Renewal Application No. 2. According to the FD-302 documenting the interview, Mifsud admitted to having met with Papadopoulos but denied having told him about any suggestion or offer from Russia.403 Additionally, according to the FD-302, Mifsud told the FBI that “he had no advance knowledge Russia was in possession of emails from the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and, therefore, did not make any offers or proffer any information to Papadopoulos.”

[snip]

Evans told us that he could not say definitively whether QI would have included this information in subsequent renewal applications without discussing the issue with the team (the FBI and QI), but Evans also said that Mifsud’s denial as described by the QIG sounded like something “potentially factually similarly situated” to the denials made by Papadopoulos that QI determined should have been included. 405

In other words, Evans would have treated both of these denials (correctly, as subsequent investigation would prove) as lies, and dealt with them however such lies are treated in FISA applications. Probably, they would be used to suggest that the individuals in question were trying to keep any interactions secret, therefore supporting rather than undermining a claim that clandestine intelligence cooperation was happening.

But there’s a detail that Papadopoulos has claimed he also included in his comments to Halper that doesn’t show up in the ellipsis-filled excerpts of Papadopoulos’ conversations with Halper. Along with admitting that he likened optimizing the WikiLeaks releases to “treason,” Papadopoulos claimed he pushed back by saying, “I really have nothing to do with Russia.” If Papadopoulos did, in fact, say anything like that, it would have amounted to proof he was lying, especially since the FBI was tracking his ongoing interactions with Sergei Millian at the time, whom they would soon open a counterintelligence investigation into. The IG’s office could not tell me whether such language appeared in the full transcript. But if such language was excluded, then it would amount to an exclusion of a material detail of the sort that the IG Report complains about FBI excluding in Page’s applications.

What makes it into a 302 or not

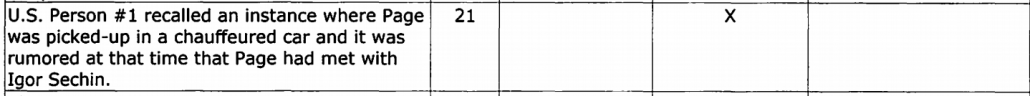

One of the Woods procedure errors the IG Report rightly describes is that the FBI 302 that purportedly included a discussion of Carter Page being picked up in a limo in Moscow in July 2016 does not actually include the reference.

A June 2017 interview by the FBI of an individual closely tied to the President of the New Economic School in Moscow who stated that Carter Page was selected to give a commencement speech in July 2016 because he was candidate Trump’s “Russia-guy.” This individual also told the FBI that while in Russia in July 2016, Carter Page was picked up in a chauffeured car and it was rumored he met with Igor Sechin. However, the FD-302 documenting this interview, which was included in the Woods File for Renewal Application No. 3, does not contain any reference to a chauffeured car picking up Carter Page. We were unable to locate any document or information in the Woods File that supported this assertion.

371 We asked both agents that interviewed this individual, Case Agent 6 and Case Agent 7, if this individual stated during the interview that Page was picked up in a chauffeured car. Case Agent 6 told us he did recall the individual making this statement; Case Agent 7 did not recall and stated he may have made the statement during a telephone interview that occurred later.

Confusingly, in the appendix where it lists this, it attributes the comment to US person 1, which is presumably how DOJ referred to the source in the application. This is not a reference to Sergei Millian, though he is referred to as Person 1 in the IG Report.

Rather, this was a reference to Yuval Weber, the son of the Schlomo Weber, the rector of the New Economic School in Moscow who invited Page to Moscow in 2016. Per the Mueller Report, Yuval Weber was interviewed on June 1, 2017 (his father was interviewed on July 28, 2017).

This is absolutely a fair complaint.

But the IG Report does not, similarly, complain about or fully incorporate something else that didn’t make an FBI 302. As it describes, the notes from at least one of the attendees at the November 21, 2016 meeting where Bruce Ohr provided context about the Steele dossier included background to Ohr’s description that Steele was “desperate” Trump not be elected.

Steele was “desperate” that Trump not be elected, but was providing reports for ideological reasons, specifically that “Russia [was] bad;”

That is, Ohr’s observation was not about a political view on the part of Steele, but was instead a comment about his concerns about Russia.

This accords with what Steele told the IG’s investigators.

When we interviewed Steele, he told us that he did not state that he was “desperate” that Trump not be elected and thought Ohr might have been paraphrasing his sentiments. Steele told us that based on what he learned during his research he was concerned that Trump was a national security risk and he had no particular animus against Trump otherwise.

Mind you, Steele’s concerns about Trump’s election should have been included in the Carter Page applications in any case. But the context of why Steele was so concerned doesn’t appear in the balance of the IG Report’s discussion of this reference, which thereby treats what the investigation showed was a concern about national security as, instead, political bias.

The FBI is always wrong and DOJ is always right

The IG Report shows remarkable consistency for treating similar behavior from people at FBI as damning while brushing off similar behavior from DOJ lawyers or managers. As I noted in this post, for example, it suggests Jim Comey should have demanded to learn more details about Bruce Ohr’s interactions with Christopher Steele in a November 2016 briefing where Ohr was mentioned, but doesn’t ask why no one in DOJ’s chain of command who got briefed in February 2017 on Ohr’s role didn’t demand more information. Effectively Comey gets held accountable for something mentioned in a briefing, but DOJ lawyers are not. The IG Report admits this explicitly, saying that because FBI would have access to more information, they should be held accountable for more.

Thus, while we believe the opportunities for learning investigative details were greater for FBI leadership than for Department leadership, we were unable to conclusively determine whether FBI leadership was provided with sufficient information, or sufficiently probed the investigative team, to enable them to effectively assess the evidence as the case progressed.

The IG Report applies the same standard to more junior people as well. For example, an Office of Intelligence lawyer excuses himself from including Carter Page’s (truthful) denials in the FISA application because the FBI agent did not flag statements for him, including in a 163-page transcript.

We found that information about the August 2016 meeting was first shared with the 01 Attorney on or about June 20, 2017, when Case Agent 6 sent the 01 Attorney a 163-page document containing the statements made by Page during the meeting. As described in Chapter Seven, Case Agent 6, to bolster probable cause, had added to the draft of FISA Renewal Application No. 3 statements that Page made during this meeting about an “October Surprise” involving an “email dump” of “33 thousand” emails. The OI Attorney told us that he used the 163-page document to accurately quote in the final renewal application Page’s statements concerning the “October Surprise,” but that he did not read the other aspects of the document and that the case agent did not flag for him the statements Page made about Manafort. The OI Attorney told us that these statements, which were available to the FBI before the first application, should have been flagged by the FBI for inclusion in all of the FISA applications because they were relevant to the court’s assessment of the allegations concerning Manafort’s use of Page as an intermediary with Russia. Case Agent 6 told us that he did not know that Page made the statement about Manafort because the August 2016 meeting took place before he was assigned to the investigation. He said that the reason he knew about the “October Surprise” statements in the document was that he had heard about them from Case Agent 1 and did a word search to find the specific discussion of that topic.

Regarding the similar statement Page made during one of his March 2017 interviews with the FBI, the 01 Attorney told us that Case Agent 6 also did not flag this statement for him, but added that he (OI Attorney) should have noticed the statement himself in the interview summary Case Agent 6 forwarded to him on March 24, 2017, since it was only five pages, and the 01 Attorney had read the entire document.

[snip]

Case Agent 6 told us that he did not know that Page made the statement about Manafort because the August 2016 meeting took place before he was assigned to the investigation. He said that the reason he knew about the “October Surprise” statements in the document was that he had heard about them from Case Agent 1 and did a word search to find the specific discussion on that topic. Case Agent 6 further told us that he added the “October Surprise” statements in consultation with the 01 Attorney after the 01 Attorney asked him if there was other information in the case file that would help support probable cause.

In reality, both the FBI Agent and the OI lawyer should be held to the standard of reading the materials in question.

A more remarkable example comes in a passage where the IG Report claims NSD had “no indication” of seven problems it found in the first Carter Page application, but then describes that the FBI Agent had included details on one of them in an email to the OI lawyer in support of the application.

3. Omitted information relevant to the reliability of Person 1, a key Steele sub-source (who, as previously noted, was attributed with providing the information in Report 95 and some of the information in Reports 80 and 102 relied upon in the application), namely that (1) Steele himself told members of the Crossfire Hurricane team that Person 1 was a “boaster” and an “egoist” and “may engage in some embellishment” and (2) the FBI had opened a counterintelligence investigation on Person 1 a few days before the FISA application was filed;

[snip]

We found no indication that NSD officials were aware of these issues at the time they prepared or reviewed the first FISA application. Regarding the third listed item above, the OI Attorney who drafted the application had received an email from Case Agent 1 before the first application was filed containing the information about Steele’s “boaster” and “embellishment” characterization of Person 1, whom the FBI believed to be Source E in Report 95 and the source of other allegations in the application derived from Reports 80 and 102. This information was part of a lengthy email that included descriptions of various individuals in Steele’s source network and other information Steele provided to the Crossfire Hurricane team in early October 2016. The OI Attorney told us that he did not recall the Crossfire Hurricane team flagging this issue for him or that he independently made the connection between this sub-source and Steele’s characterization of Person 1 as an embellisher. We believe Case Agent 1 should have specifically discussed with the OI Attorney the FBI’s assessment that this subsource was Person 1, that Steele had provided derogatory information regarding Person 1, and that [redacted], so that OI could have assessed how these facts might impact the FISA application.

Later, the IG Report explicitly admits that it is doing this, holding the FBI responsible because the DOJ lawyers didn’t read what the FBI provided them.

While we found isolated instances where a case agent forwarded documentation to the OI Attorney that included, among other things, information omitted from the FISA applications, we noted that, in those instances, the Crossfire Hurricane team did not alert the OI Attorney to the information.

It then claims that FBI did not give OI a chance to consider information it shared with OI.

We do not speculate as to whether or how this additional information might have influenced the decisions of senior leaders who supported the applications, if they had known all of the relevant information. Nevertheless, we believe it was the obligation of the agents who were aware of the information to ensure that OI and the decision makers had the opportunity to consider it, both to decide whether to proceed with the applications and, if so, how to present this information to the court.

From a policy perspective, the IG Report provides a more useful observation about the FBI-OI relationship that explains and should be fixed to address the problem of OI not integrating information FBI provided them: that the lawyers in OI aren’t involved in an investigative role like prosecutors who would file a criminal warrant application.

As described in Chapter Five, NSD officials told us that the nature of FISA practice requires that 01 rely on the FBI agents who are familiar with the investigation to provide accurate and complete information. Unlike federal prosecutors, OI attorneys are usually not involved in an investigation, or even aware of a case’s existence, unless and until OI receives a request to initiate a FISA application. Once OI receives a FISA request, OI attorneys generally interact with field offices remotely and do not have broad access to FBI case files or sensitive source files. NSD officials cautioned that even if OI received broader access to FBI case and source files, they still believe that the case agents and source handling agents are better positioned to identify all relevant information in the files. In addition, NSD officials told us that OI attorneys often do not have enough time to go through the files themselves, as it is not unusual for OI to receive requests for emergency authorizations with only a few hours to evaluate the request.

Rather than incorporating this important observation into its findings, thereby identifying a process failure with FISA that likely applies to all FISA applications, the IG Report instead just blames the FBI. This is equivalent to downplaying honest explanations for Carter Page’s enthusiasm for sharing non-public information with Russian intelligence officers — that CIA said it was okay (which would not explain all of his interactions with Russian spies in any case).

Again, I’m not knocking the report as a whole. In much the same way that there was a lot of evidence against Carter Page even given the problems with his FISA applications, the IG Report is important and valuable in spite of these problems.

But the problems probably provide a far better answer to the question posed by the IG Report as a whole: what explains the errors or missing information in the Carter Page FISA applications. In a really worthwhile podcast on the report, Stewart Baker suggests the disproportionate blame on FBI may arise from the scope of DOJ IG’s authority; it is not permitted to criticize the work of prosecutors. Assessed along with DOJ IG’s past reports on Trump targets, these errors may raise questions of bias, whether that bias stems from a failure to reframe investigative missions the IG receives to eliminate the assumptions who assign them (as almost certainly happened in the IG Report’s treatment of Bruce Ohr), or a more general willingness to serve as Trump’s hatchetman (I’ll return to this in a post on Andrew McCabe’s lawsuit).

But the explanation could be and — for many of these errors — likely is more simple. As Julian Sanchez argued convincingly, the better explanation is probably confirmation bias. Once DOJ IG came to believe FBI fucked up (possibly as early as the report on the Hillary investigation), everything it found seemed to confirm that conclusion. That’s natural and not something I am immune to either (and I’m sure I’ll have my share of embarrassing errors in this post!). But particularly with FISA — which disproportionately is used with people with Chinese or Islamic ties — that kind of confirmation bias can end up being discriminatory.

That, again, provides perhaps the most important lesson this report offers about FISA. DOJ IG was able to fix several of its errors because making the report public subjected its work to scrutiny that identified the errors; I’ve been able to point to others simply by an extended deep dive or consulting other public records on these matters, like a Judicial Watch FOIA or the Mueller Report. The problem with FISA applications, however, is they never get exposed to such scrutiny, so that errors that might be addressed in criminal affidavits aren’t for FISA applications. In that Baker podcast, David Kris argued that one way to fix these problems is to let any defendants against whom FISA is used in a prosecution access their application (something that could be done under the CIPA process).

Committing the same kinds of errors it criticizes doesn’t make this IG Report useless or wrong about its key findings on the problems with the Carter Page application (though it does make the recommendations that the FBI and Bruce Ohr be disciplined far weaker). But it does make a meta point about the value of transparency for counteracting confirmation bias.

OTHER POSTS ON THE DOJ IG REPORT

Overview and ancillary posts

DOJ IG Report on Carter Page and Related Issues: Mega Summary Post

The DOJ IG Report on Carter Page: Policy Considerations

Timeline of Key Events in DOJ IG Carter Page Report

Crossfire Hurricane Glossary (by bmaz)

Facts appearing in the Carter Page FISA applications

Nunes Memo v Schiff Memo: Neither Were Entirely Right

Rosemary Collyer Responds to the DOJ IG Report in Fairly Blasé Fashion

Report shortcomings

The Inspector General Report on Carter Page Fails to Meet the Standard It Applies to the FBI

“Fact Witness:” How Rod Rosenstein Got DOJ IG To Land a Plane on Bruce Ohr

Eleven Days after Releasing Their Report, DOJ IG Clarified What Crimes FBI Investigated

Factual revelations in the report

Deza: Oleg Deripaska’s Double Game

The Damning Revelations about George Papadopoulos in a DOJ IG Report Claiming Exculpatory Evidence

The Carter Page IG Report Debunks a Key [Impeachment-Related] Conspiracy about Paul Manafort

Sam Clovis Responded to a Question about Russia Interfering in the Election by Raising Voter ID