The Nuances of the Carter Page Application

I’ve now finished a close read of the last Carter Page FISA application. I think the contents bring a lot more nuance to the discussion of it over the last three years. This post will try to lay out some of that nuance.

Hot and cold running Carter Page descriptions

In most ways, the declassified application tracks the DOJ IG Report and shows how the problems with the application in practice. One newly declassified example conservatives have pointed to shows that FBI Agents believed that Page’s media appearances in spring 2017 were just an attempt to get a book contract.

The FBI also notes that Page continues to be active in meeting with media outlets to promote his theories of how U.S. foreign policy should be adjusted with regard to Russia and also to refute claims of his involvement with Russian Government efforts to influence the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. [redacted–sensitive information] The believes this approach is important because, from the Russian Government’s point-of-view, it continues to keep the controversy of the election in the front of the American and world media, which has the effect of undermining the integrity of the U.S. electoral process and weakening the effectiveness of the current U.S. Administration. The FBI believes Page also may be seeking media attention in order to maintain momentum for potential book contracts. (57)

Even if Page were doing media to get a book contract, short of being charged and put under a court authorized gag, there’s nothing that prevents him from telling his story. He’s perfectly entitled to overtly criticize US foreign policy. And as so often happens when intelligence analysis sees any denials as a formal Denial and Deception strategy, the FBI allowed no consideration to the possibility that some of his denials were true.

Julian Sanchez argued when the IG Report came out that FBI’s biases were probably confirmation bias, not anti-Trump bias, and this is one of the many examples that supports that.

One specific Page denial that turned out to be true — that he was not involved in the Ukraine platform issue — is even more infuriating reading in declassified form. As the IG Report noted, by the time FBI filed this last application, there were several piece of evidence that JD Gordan was responsible for preventing any platform change.

An FBI March 20, 2017 Intelligence Memorandum titled “Overview of Trump Campaign Advisor Jeff D. [J.D.] Gordon” again attributed the change in the Republican Platform Committee’s Ukraine provision to Gordon and an unnamed campaign staffer. The updated memorandum did not include any reference to Carter Page working with Gordon or communicating with the Republican Platform Committee. On May 5, 2017, the Counterintelligence Division updated this Intelligence Memorandum to include open source reporting on the intervention of Trump campaign members during the Republican platform discussions at the Convention to include Gordon’s public comments on his role. This memorandum still made no reference to involvement by Carter Page with the Republican Platform Committee or with the provision on Ukraine.

On June 7, 2017, the FBI interviewed a Republican Platform Committee member. This interview occurred three weeks before Renewal Application No. 3 was filed. According to the FBI FD-302 documenting the interview, this individual told the FBI that J.D. Gordon was the Trump campaign official that flagged the Ukrainian amendment, and that another person (not Carter Page) was the second campaign staffer present at the July 11 meeting of the National Security and Defense Platform Subcommittee meeting when the issue was tabled.

Although the FBI did not develop any information that Carter Page was involved in the Republican Platform Committee’s change regarding assistance to Ukraine, and the FBI developed evidence that Gordon and another campaign official were responsible for the change, the FBI did not alter its assessment of Page’s involvement in the FISA applications. Case Agent 6 told us that when Carter Page denied any involvement with the Republican Platform Committee’s provision on Ukraine, Case Agent 6 “did not take that statement at face value.” He told us that at the time of the renewals, he did not believe Carter Page’s denial and it was the team’s “belief” that Carter Page had been involved with the platform change.

But the application’s treatment of this issue doesn’t just leave out that information. The utterly illogical explanation of why the FBI believed he had a role in the platform — which was quoted in the IG Report — appears worse in context.

During these March 2017 interviews, the FBI also questioned Page about the above-referenced reports from August 2016 that Candidate #1’s campaign worked to make sure Political Party #1’s platform would not call for giving weapons to Ukraine to fight Russian and rebel forces [this matter is discussed on pgs. 25-26]. According to Page, he had no part in the campaign’s decision. Page stated that an identified individual (who previously served as manager of Candidate #1’s campaign) more likely than not recommended the “pro-Russian” changes. As the FBI believes that Page also holds pro-Russian views and appears to still have been a member of Candidate #1’s campaign in August 2016, the FBI assesses that Page may have been downplaying his role in advocating for the change to Political Party #1’s platform. (55)

(Here’s the March 16, 2017 interview.)

It’s not just that the FBI had about five other pieces of evidence that suggested Page was not involved, but for the FBI, it was enough that he was pro-Russian to suggest Page would have had the influence and bureaucratic chops to make it happen, even in the absence of any evidence to the fact. Add in the fact that FBI obtained a pen register on Page as part of this application (as reflected by notations in the margin of redacted material), and the fact that FBI didn’t track what communications he did or did not have at any time is particularly inexcusable.

So there’s abundant evidence in the Page applications that FBI acted like they normally do, seeing in every denial yet more evidence of guilt.

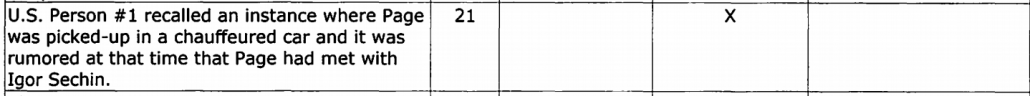

That said, the application does show more to explain why the FBI suspected Page in the first place and continued to have questions about his veracity until the end. For example, here’s the full explanation of how Page came to tell a Russian minister he had been the guy that Viktor Podobnyy was recruiting.

Based on information provided by Page during this [March 2016] interview, the FBI determined that Page’s relationship with Podobnyy was primarily unidirectional, with Page largely providing Podobnyy open source information and contact introductions. During one interview, Page told the FBI that he approached a Russian Minister, who was surrounded by Russian officials/diplomats, and “in the spirit of openness,” Page informed the group that he was “Male-1” in the Buryakov complaint. (16-17)

The FBI took this both as Page’s own confirmation that he was the person in the complaint, which in turn meant that Page knew he was being recruited, and, having learned that, sought ought well-connected Russians to identify himself as such.

As the application laid out later, Page at first denied what he had previously told the FBI about this incident and the Russians who had previously tried to recruit him in his March 2017 interviews. (This occurred in his March 16, 2017 interview.)

In a reference to the Buryakov complaint, Page stated that “nobody knows that I’m Male-1 in this report,” and also added that he never told anyone about this. As discussed above, however, during a March 2016 interview with the FBI regarding his relationship with Podobnyy, Page told the FBI he informed a group of Russian officials that he (Page) was “Male-1” in the Buryakov complaint. Thus, during the March 2017 interview, the FBI specifically asked Page if he told any colleague that he (Page) was “Male-1.” In response, Page stated that there was a conversation with a Russian Government official at the United Nations General Assembly The FBI again asked Page if he had told anyone that he was “Male-1.” Page responded that he “forgot the exact statement.”

Note, Page’s 302 quotes Page as telling the Minister, “I didn’t do anything [redacted],” but it’s unclear (given the b3 redaction) whether that relays what Page said in March 2017 or if the b3 suggests FBI learned this via other means. But the redacted bit remains one of the sketchier parts of this.

The application also describes how Page denied having a business relationship with Aleksandr Bulatov, the first presumed time Russia tried to recruit him, claiming he may have had lunch with him in New York. That Page claimed only to have had lunch with him is all the more absurd since this was the basis for his supposed cooperation with the CIA.

Having seen how Page handled his HPSCI interview and TV interviews, it’s not surprising to see he denied ties he earlier bragged about (which, in any case, undermines any claim he was operating clandestinely). But at best, Page didn’t deny the key thing he could have to avert suspicion: to admit (as George Papadopoulos readily did) that he was overselling his access in Russia to the Trump campaign, in emails the FBI presumably obtained using FISA. Nothing in the IG Report rebuts the claim that Page claimed things in communications that provided basis to believe he was lying (the actual communications are redacted in the applications because all of the FISA collection targeted at Page has been sequestered). So while the FBI did a bunch of inexcusable things with Page, there were things that Page did — and never explained — that explain the FBI’s sustained suspicion of him.

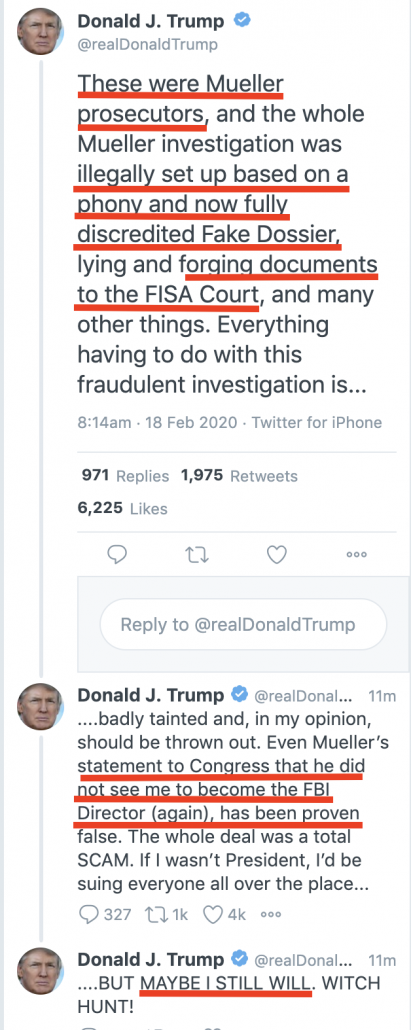

An explanation for some of the GOP’s core beliefs about the dossier and the investigation

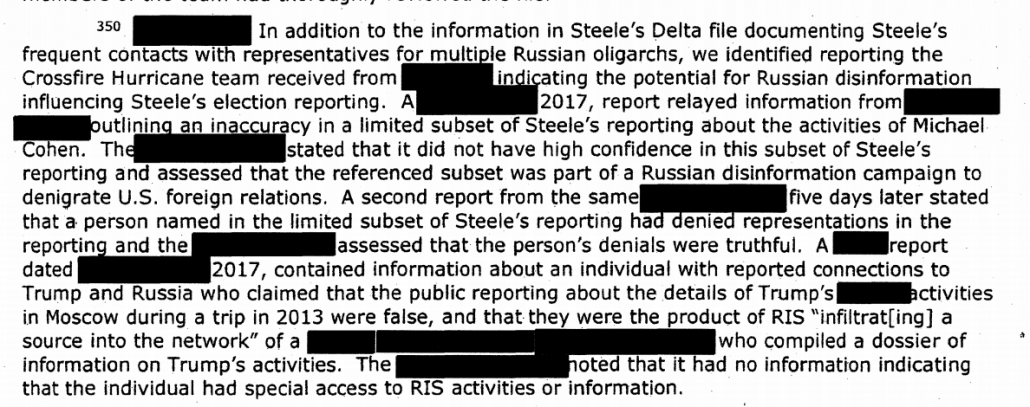

The release of the full application also helps to explain how Republicans came to have certain beliefs about the Steele dossier and the Russian investigation. Take this passage:

Source #1 reported the information contained herein to the FBI over the course of several meetings with the FBI from in or about June 2016 through August 2016.

The passage is slightly inaccurate: Mike Gaeta first got reports from Christopher Steele in early July.

Shortly before the Fourth of July 2016, Handling Agent 1 told the OIG that he received a call from Steele requesting an in-person meeting as soon as possible. Handling Agent 1 said he departed his duty station in Europe on July 5 and met with Steele in Steele’s office that day. During their meeting, Steele provided Handling Agent 1 with a copy of Report 80 and explained that he had been hired by Fusion GPS to collect information on the relationship between candidate Trump’s businesses and Russia.

Since initial details of Steele’s reporting have been made public, the frothy right has been unable to understand that information doesn’t necessarily flow instantaneously inside of or between large bureaucracies. And having read this line, I assume Kash Patel would have told Devin Nunes and Trey Gowdy that it was proof that the FBI predicated the investigation on the Steele dossier, because “the FBI” had Steele’s reports a month before opening the investigation into Trump’s aides (though, in fact, that was months after NYFO had opened an investigation into Page). The IG Report, however, explains in detail about how there was a bit of a delay before Steele’s handler sent his reports to the NY Field Office, a delay there for a while, and a further delay after a member of the Crossfire Hurricane team asked NYFO to forward anything they had. As a result, the CH team didn’t receive the first set of Steele reports until September 19, over a month after the investigation started.

On August 25, 2016, according to a Supervisory Special Agent 1 (SSA 1) who was assigned to the Crossfire Hurricane investigation, during a briefing for then Deputy Director Andrew McCabe on the investigation, McCabe asked SSA 1 to contact NYFO about information that potentially could assist the Crossfire Hurricane investigation. 225 SSA 1 said he reached out to counterintelligence agents and analysts in NYFO within approximately 24 hours following the meeting. Instant messages show that on September 1, SSA 1 spoke with a NYFO counterintelligence supervisor, and that the counterintelligence supervisor was attempting to set up a call between SSA 1 and the ADC. On September 2, 2016, Handling Agent 1, who had been waiting for NYFO to inform him where to forward Steele’s reports, sent the following email to the ADC and counterintelligence supervisor: “Do we have a name yet? The stuff is burning a hole.” The ADC responded the same day explaining that SSA 1 had created an electronic sub-file for Handling Agent 1 in the Crossfire Hurricane case and that he

In any other world, this delay — as well as a delay in sharing derogatory information freely offered by Bruce Ohr and Kathleen Kavalec — would be a scandal about not sharing enough information. But instead, this passage about when FBI received the files likely plays a key part of an unshakeable belief that the dossier played a key role in predicating the investigation, which it does not.

Similarly, declassification of the application helps to explain why the frothy right believes that claims George Papadopoulos made to Stefan Halper and another informant in fall 2016 should have undermined the claims FBI made.

To be clear: the frothy right is claiming Papadopoulos’s denials should be treated as credible even after he admitted to a second informant that he told the story he did to Halper about Trump campaign involvement in the leaked emails because he believed if he had said anything else, Halper would have gone to the CIA about it. The FBI, however, believed the claims to be lies in real time, and on that (unlike Carter Page’s denials) the record backs them. There’s even a footnote (on page 11) that explicitly said, “the FBI believes that Papadopoulos provided misleading or incomplete information to the FBI” in his later FBI interviews.

That said, the way Papadopoulos is used in this application is totally upside down. A newly declassified part of the footnote describing Steele’s partisan funding claims that Papadopoulos corroborates Steele’s reporting (the italicized text is newly declassified).

Notwithstanding Source #1’s reason for conducting the research into Candidate #1’s ties to Russia, based on Source #1’s previous reporting history with the FBI, whereby Source #1 provided reliable information to the FBI, the FBI believes Source #1’s herein to be credible. Moreover, because of outside corroborating circumstances discussed herein, such as the reporting from a friendly foreign government that a member of Candidate #1’s team received a suggestion from Russia that Russia could assist with the release of information damaging to Candidate #2 and Russia’s believed hack and subsequent leak of the DNC e-amils, the FBI assesses that Source #1’s reporting contained herein is credible.

This is the reverse of how the IG Report describes things, which explains that the DNC emails came out, Australia decided to alert the US Embassy in London about what Papadopoulos had said three months earlier, which led the FBI to predicate four different investigations (Page, Papadopoulos, Mike Flynn, and Paul Manafort; though remember that NYFO had opened an investigation into Page in April) to see if any of the most obvious Trump campaign members could explain why Russia thought it could help the Trump campaign beat Hillary by releasing emails. The Steele dossier certainly seemed to confirm questions raised by the Australia report (which explains why the FBI was so susceptible, to the extent this was disinformation, to believing it, and why, to the extent it was disinformation, it was incredibly well-crafted). The Steele dossier seemingly confirmed the fears raised by the Australia report, not vice versa. It seems like circular logic to then use Papadopoulos to “corroborate” the Steele dossier. That has, in turn, led the right to think undermining the original Australian report does anything to undermine the investigation itself, even though by the end of October Papadopoulos had sketched out the outlines of what happened with Joseph Mifsud and discussed wanting to cash in on it, and Papadopoulos continued to pursue this Russian relationship, including a secret back channel meeting in London, well into the summer.

Finally, I’m more sympathetic, having read this full application, to complaints about the way FBI uses media accounts — though for an entirely different reason than the frothy right. The original complaint on this point misread the way the FBI used the September 23 Michael Isikoff article reporting on Page, suggesting it was included for the facts about the meeting rather than the denials from Page and the campaign presented in it. The discussion appears in a section on “Page’s denial of cooperation.” And — as I’ve noted before — the FBI always sourced that story to the Fusion GPS effort, even if they inexcusably believed that Glenn Simpson, and not Steele, was the “well-placed Western intelligence source” cited in the article.

But with further declassification, the way the application relied on two articles about the Ukraine platform to establish what the campaign had actually done (see page 25), rather than refer to the platform itself — or, more importantly, Trump’s own comments about policy, which I’ll return to — appears more problematic (not least because FBI confused the timing of one of those reports with the actual policy change.

Steele and Sergei Millian as uniquely correct about WikiLeaks

There’s another thing about sourcing in this application (which carries over to what I’ve often seen in FBI affidavits). While there are passages discussing the larger investigation into Russia’s 2016 operation that remain redacted (and indeed, there’s a substitution of a redaction with “FBI” on page 7 which probably hides that the IC as a whole continued to investigate Russian hacking), key discussions of that investigation cite to unclassified materials, even in a FISA application that would have under normal circumstances never been shared publicly. For example, the discussion describing attribution of the operation to Russia from pages 6 to 10 largely relies on the October 7 joint statement and Obama’s sanctions statement, not even the January 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment, much less (with the exception of two redacted passages) anything more detailed.

Even ignoring secret government sources, there was a whole lot more attributing Russia and WikiLeaks’s role in the hack-and-leak, especially by June 2017. Yet the Page application doesn’t touch any of that.

And that makes the way the application uses the allegations — attributed to Sergei Millian — to make knowable information about the WikiLeaks dump tie to unsupported information in the dossier all the more problematic. As parroted in the application, this passage interlaces true, public, but not very interesting details with totally unsupported allegations:

According to information provided by Sub-Source [redacted] there was a well-developed conspiracy of co-operation between them [assessed to be individuals involved in Candidate #1’s campaign] and the Russian leadership.” Sub-Source [redacted] reported that the conspiracy was being managed by Candidate #1’s then campaign manager, who was using, among others, foreign policy advisor Carter Page as an intermediary. Sub-Source [redacted] further reported that the Russian regime had been behind the above-described disclosure of DNC e-mail messages to WikiLeaks. Sub-Source [redacted] reported that WikiLeaks was used to create “plausible deniability,” and that the operation had been conducted with the full knowledge and support of Candidate #1’s team, which the FBI assessed to include at least Page. In return, according to Sub-Source [redacted], Candidate #1’s team, which the FBI assessed to include at least Page, agreed to sideline Russian intervention in Ukraine as a campaign issue and to raise U.S.NATO defense commitments in the Baltics and Eastern Europe to deflect attention away from Ukraine.

The DOJ IG report describes how FBI responded to this report by (purportedly) examining the reliability of Steele and his sources closely.

The FISA application stated that, according to this sub-source, Carter Page was an intermediary between Russian leadership and an individual associated with the Trump campaign (Manafort) in a “well-developed conspiracy of co-operation” that led to the disclosure of hacked DNC emails by Wikileaks in exchange for the Trump campaign team’s agreement, which the FBI assessed included at least Carter Page, to sideline Russian intervention in Ukraine as a campaign issue. The application also stated that this same sub-source provided information contained in Steele’s Report 80 that the Kremlin had been feeding information to Trump’s campaign for an extended period of time and that the information had reportedly been “very helpful,” as well as information contained in Report 102 that the DNC email leak had been done, at least in part, to swing supporters from Hillary Clinton to Donald Trump. 300 Because the FBI had no independent corroboration for this information, as witnesses have mentioned, the reliability of Steele and his source network was important to the inclusion of these allegations in the FISA application.

Except there would seem to be another necessary step: to first identify how much of this report cobbled together stuff that was already public — which included Russia’s role, the purpose of using WikiLeaks, Carter Page’s trip to Russia (but not specifics of his meetings there), and — though the application got details of what happened with Ukraine in the platform wrong — the prevention of a change to the platform. On these details, Steele was not only not predictive, he was derivative. Putting aside the problems with the three different levels of unreliable narrators (Steele, his Primary Subsource, and Millian), all of whom had motives to to package this information in a certain way, the fact that these claims clearly included stuff that had been made available weeks earlier should have raised real questions (and always did for me, when I was reading this dossier). Had the FBI separated out what was unique and timely in these allegations, they would have looked significantly different (not least because they would have shown Steele’s network was following public disclosures on key issues).

This is not the kompromat you’re looking for

Which brings me to perhaps the most frustrating part of this application.

As I started arguing at least by September 2017 (and argued again and again and again), to the extent the dossier got filled with disinformation, it would have had the effect of leading Hillary’s campaign to be complacent after learning they had been hacked, because according to the dossier, the Russians planned to leak years old FSB intercepts from when Hillary visited Russia, not contemporaneous emails pertaining to her campaign and recent history. It might even have led the Democrats to dismiss the possibility that the files Guccifer 2.0 was releasing were John Podesta files, delaying any response to the leak that would eventually come in October.

To the extent the dossier was disinformation, it gave the Russian operation cover to regain surprise for their hack-and-leak operation. At least with respect to the Democrats, that largely worked.

And, even though the Australians apparently believed the DNC release may have confirmed Papadopoulos prediction that Russia would dump emails, it appears to have partly worked with the FBI, as well. This passage should never appear in an application that derived from a process leading from the DNC emails to the shared tip about Papadopoulos to a request to wiretap Page:

According to reporting from Sub-Source [redacted] this dossier had been compiled by the RIS over many years, dating back to the 1990s. Further, according to Sub-Source [redacted] his dossier was, by the direct instructions of Russian President Putin, controlled exclusively by Senior Kremlin Spokesman Dmitriy Peskov. Accordingly, the FBI assesses that Divyekin received direction by the Russian Government to disclose the nature and existence of the dossier to Page. In or about June 2016, Sub-Source [redacted] reported that the Kremlin had been feeding information to Candidate #1’s campaign for an extended period of time. Sub-Source [redacted] also reported that the Kremlin had been feeding information to Candidate #1’s campaign for an extended period of time and added that the information had reportedly been “very helpful.” The FBI assesses the information funneled by the Russians to Page was likely part of Russia’s efforts to influence the 2016 U.S. Presidential election.

Note, the FBI contemporaneously — though not after December 9, 2016 — would not have had something Hillary’s team did, the July Steele report on Russia’s claimed lack of hacking success that the FBI should have recognized as utterly wrong. Still, the earliest Steele reports they did have said the kompromat the Russians were offering was stale intercepts. At the very least, one would hope that would raise questions about why someone with purported access to top Kremlin officials didn’t know about the hack-and-leak operation. But the FBI seems to have expected there might be something more.

Trump clearly was not, but should have been, the target earlier than he was

There’s an irony about the complaints I lay out here: they suggest that Trump should have been targeted far earlier than he was.

The Page application rests on the following logic: One of the notably underqualified foreign policy advisors that Trump rolled out to great fanfare in March 2016 told someone, days later, that Russia had offered to help Trump by releasing damaging information on Hillary. The July dump of DNC emails suggested that Papadopoulos’ knowledge foreknowledge may have been real (and given Mifsud’s ties to someone with links to both the IRA and GRU people behind the operation, it probably was). The temporal coincidence of his appointment and that knowledge seemed to tie his selection as an advisor and that knowledge (and in his case, because Joseph Mifsud only showed an interest in Papadopoulos after learning he was a Trump advisor, that turned out to be true). That made the trip to Russia by another of these notably underqualified foreign policy advisors to give a speech he was even more underqualified to give, all the more interesting, especially the way the Trump people very notably reversed GOP hawkishness on Ukraine days after Page’s return.

In other words, the FBI had evidence — some of it now understood to be likely disinformation, and was trying to understand, how, after Trump shifted his focus to foreign policy, he shifted to a more pro-Russian stance in seeming conjunction with Russia delivering on their promise (shared with foreign policy advisor Papadopoulos) to help Trump by releasing the DNC emails.

It turns out the change in policy was real. And JD Gordan attributed his intervention on the RNC platform, in contravention of direction from policy director John Mashburn, to Trump’s own views.

Gordon reviewed the proposed platform changes, including Denman’s.796 Gordon stated that he flagged this amendment because of Trump’s stated position on Ukraine, which Gordon personally heard the candidate say at the March 31 foreign policy meeting-namely, that the Europeans should take primary responsibility for any assistance to Ukraine, that there should be improved U.S.-Russia relations, and that he did not want to start World War III over that region.797 Gordon told the Office that Trump’s statements on the campaign trail following the March meeting underscored those positions to the point where Gordon felt obliged to object to the proposed platform change and seek its dilution.798

[snip]

According to Denman, she spoke with Gordon and Matt Miller, and they told her that they had to clear the language and that Gordon was “talking to New York.”803 Denman told others that she was asked by the two Trump Campaign staffers to strike “lethal defense weapons” from the proposal but that she refused. 804 Demnan recalled Gordon saying that he was on the phone with candidate Trump, but she was skeptical whether that was true.805 Gordon denied having told Denman that he was on the phone with Trump, although he acknowledged it was possible that he mentioned having previously spoken to the candidate about the subject matter.806 Gordon’s phone records reveal a call to Sessions’s office in Washington that afternoon, but do not include calls directly to a number associated with Trump.807 And according to the President’s written answers to the Office’s questions, he does not recall being involved in the change in language of the platform amendment. 808

Gordon stated that he tried to reach Rick Dearborn, a senior foreign policy advisor, and Mashburn, the Campaign policy director. Gordon stated that he connected with both of them (he could not recall if by phone or in person) and apprised them of the language he took issue with in the proposed amendment. Gordon recalled no objection by either Dearborn or Mashburn and that all three Campaign advisors supported the alternative formulation (“appropriate assistance”).809 Dearborn recalled Gordon warning them about the amendment, but not weighing in because Gordon was more familiar with the Campaign’s foreign policy stance.810 Mashburn stated that Gordon reached him, and he told Gordon that Trump had not taken a stance on the issue and that the Campaign should not intervene.811

[snip]

Sam Clovis, the Campaign’s national co-chair and chief policy advisor, stated he was surprised by the change and did not believe it was in line with Trump’s stance.816 Mashburn stated that when he saw the word “appropriate assistance,” he believed that Gordon had violated Mashburn’s directive not to intervene.817

Sam Clovis would ultimately testify there had been a policy change around the time of the March 31 meeting (though Clovis’ testimony changed wildly over the course of a day and conflicted with what he told Stefan Halper).

Clovis perceived a shift in the Campaign’s approach toward Russia-from one of engaging with Russia through the NATO framework and taking a strong stance on Russian aggression in Ukraine.

But (as noted above), to lay this out in the Page application, the FBI sourced to secondary reporting of the policy change rather than to the platform itself. More notably, in spite of all this happening after late July 2016, there’s no mention of Trump’s press conference on July 27, 2016, where he asked Russia to go find more Hillary emails (and they almost immediately started hacking Hillary’s personal accounts), said he’d consider recognizing Russia’s annexation of Crimea and lifting sanctions, and lied about his ongoing efforts to build a tower in Russia.

Trump directed Mueller to a transcript of the press conference, I’ve put excerpts below. They’re a good reminder that at the same press conference where Trump asked Russia to find Hillary’s emails (and in seeming response to which, GRU officers targeted Hillary’s personal office just five hours later), Trump suggested any efforts to build a Trump Tower in Moscow were years in the past, not ongoing. After the press conference, Michael Cohen asked about that false denial, and Trump “told Cohen that Trump Tower Moscow was not a deal yet and said, ‘Why mention it if it is not a deal?’” He also said they’d consider recognizing Russia’s seizure of Crimea, which makes Konstantin Kilimnik’s travel — to Moscow the next day, then to New York for the August 2 meeting at which he and Paul Manafort discussed carving up Ukraine at the same meeting where they discussed how to win Michigan — all the more striking. Trump’s odd answer to whether his campaign “had any conversations with foreign leaders” to “hit the ground running” may reflect Mike Flynn’s meetings with Sergei Kislyak to do just that.

In other words, rather than citing Trump’s language itself, which in one appearance tied ongoing hacking to an even more dramatic policy change than reflected in the platform, the Carter Page application cited secondary reporting, some of it post-dating this appearance.

Mueller asked Trump directly about two of the things he said in this speech (the Russia if you’re listening comment and the assertion they’d look at recognizing Crimea) and obliquely about a third (his public disavowals of Russian business ties). Trump refused to answer part of one of these questions entirely, and demonstrably lied about another. Publicly, Mueller stated that Trump’s answers were totally inadequate. And these statements happened even as his campaign manager and Konstantin Kilimnik were plotting a clandestine meeting to talk about carving up Ukraine.

The FBI may have done this to stay way-the-fuck away from politics — though, to be clear, Trump’s call on Russia to find more Hillary emails in no way fits the bounds of normal political speech.

But by doing do, they ended up using far inferior sourcing, and distracting themselves from actions more closely implicating Trump directly — actions that remain unresolved.

The Carter Page application certainly backs the conclusions of the DOJ IG Report (though it also shows I was correct that DOJ IG did not know what crimes Page was being investigated for, and as such likely got the First Amendment analysis wrong). But it also shows that the Steele dossier, which fed the FBI’s inexcusable confirmation biases, undermined the FBI investigation into questions that have not yet been fully answered.