Steve Bannon’s “Alleged” Non-Contemptuous Behavior

On Friday, the two sides in the Steve Bannon contempt prosecution filed a bunch of motions about the scope of the case. They are:

- Bannon’s 62-page Motion to Dismiss, primarily arguing that OLC memos mean he didn’t need to comply with Jan 6 Committee’s subpoena

- DOJ’s motion in limine arguing that Bannon cannot introduce OLC memos because they didn’t apply to him

- DOJ’s motion in limine arguing that Bannon cannot rely for his defense on issues he didn’t raise with the committee (some of which also appear in his MTD)

- DOJ’s motion in limine arguing that Bannon can’t claim he has an “alleged” history of compliance with subpoenas

Office of Legal Counsel memos

The fight over OLC memos is likely to get the bulk of attention, possibly even from Judge Carl Nichols (who relied on one of the OLC memos at issue in the Harriet Miers case). While there’s no telling what a Clarence Thomas clerk might do, I view this fight as mostly tactical. One way for Bannon’s attempt to fail (Nichols improbably ruling that OLC memos cannot be relied on in court) would upend the entire way DOJ treats OLC memos. That might have salutary benefits in the long term, but in the short term it would expose anyone, like Vice President Dick Cheney, who had relied on OLC memos in the past to protect themselves from torture and illegal wiretapping exposure themselves.

In my opinion this challenge is, in part, a threat to Liz Cheney.

But as DOJ (I think correctly) argues, none of this should matter. That’s because — as they show with two exhibits — none of the OLC memos apply to Bannon, and not just because he was not a government employee when he was plotting a coup.

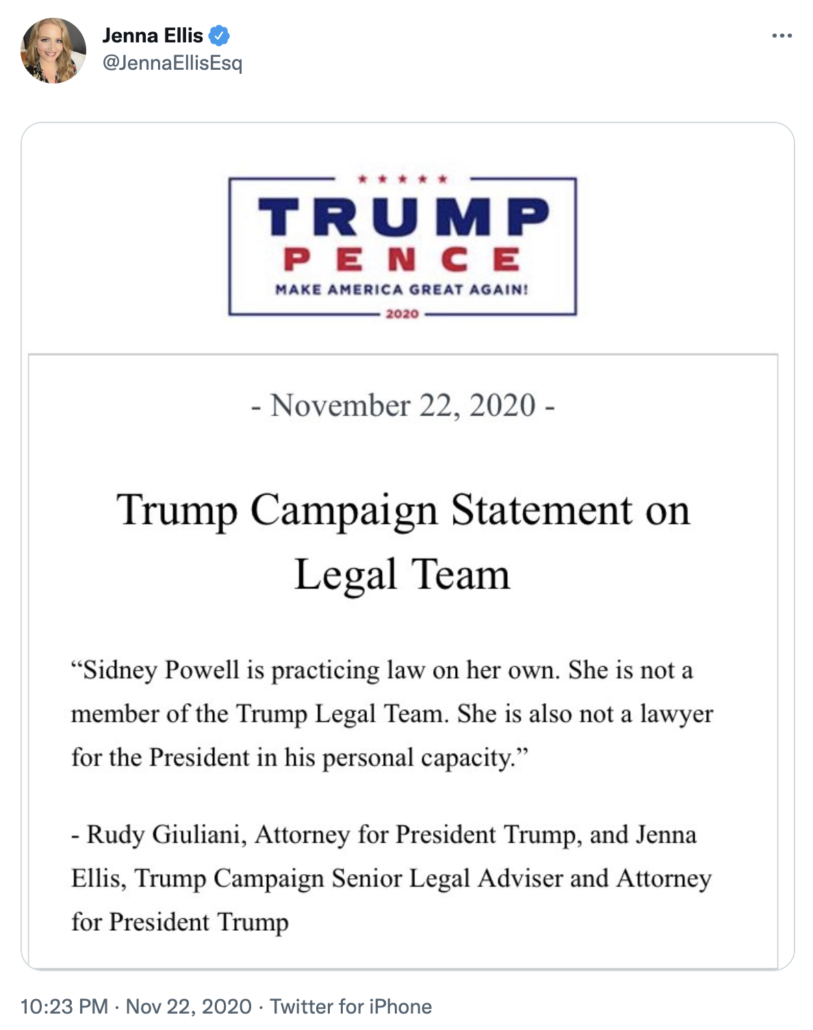

On October 6, 2021, Trump attorney Justin Clark wrote to Bannon attorney Robert Costello (citing no prior contact with Costello), instructing him not to comply to the extent permitted by law:

Therefore, to the fullest extent permitted by law, President Trump instructs Mr. Bannon to: (a) where appropriate, invoke any immunities and privileges he may have from compelled testimony in response to the Subpoena; (b) not produce any documents concerning privileged material in response to the Subpoena; and (c) not provide any testimony concerning privileged material in response to the Subpoena.

But on October 14, Clark wrote and corrected Costello about claims he had made in a letter to Benny Thompson.

Bob–I just read your letter dated October 13, 2021 to Congressman Benny Thompson. In that letter you stated that “[a]s recently as today, counsel for President Trump, Justin Clark Esq., informed us that President Trump is exercising his executive privilege; therefore he has directed Mr. Bannon not to produce documents or testify until the issue of executive privilege is resolved.”

To be clear, in our conversation yesterday I simply reiterated the instruction from my letter to you dated October 6, 2021, and attached below.

Then again on October 16, Clark wrote Costello stating clearly that Bannon did not have immunity from testimony.

Bob–In light of press reports regarding your client I wanted to reach out. Just to reiterate, our letter referenced below didn’t indicate that we believe there is immunity from testimony for your client. As I indicated to you the other day, we don’t believe there is. Now, you may have made a different determination. That is entirely your call. But as I also indicated the other day other avenues to invoke the privilege — if you believe it to be appropriate — exist and are your responsibility.

In other words, before Bannon completely blew off the Committee, Trump’s lawyer had told him not to do it on Trump’s account. (See this post which captures how Robert Costello had tried to bullshit his way through this.) That, by itself, should kill any claim that he was relying on an OLC memo.

Bannon’s prior (alleged) non-contemptuous past behavior

For different reasons, I’m a bit more interested in DOJ’s attempt to prevent Bannon from talking about what a good, subpoena-obeying citizen he has been in the past. Costello had made this argument to DOJ in an interview Bannon is trying to get excluded.

DOJ argues, uncontroversially, that because Bannon’s character is not an element of the offense, such evidence of prior compliance with a subpoena would be irrelevant.

Just as the fact that a person did not rob a bank on one day is irrelevant to determining whether he robbed a bank on another, whether the Defendant complied with other subpoenas or requests for testimony—even those involving communications with the former President—is irrelevant to determining whether he unlawfully refused to comply with the Committee’s subpoena here.

I expect Judge Nichols will agree.

What I’m interested in, though, is the way the filing refers to Bannon’s past compliance with subpoenas as “alleged.” It does so nine times:

The Defendant has suggested that, because he (allegedly) was not contemptuous in the past, he is not a contemptuous person and was not, therefore, contemptuous here.

[snip]

Mr. Costello advised that the Defendant had testified once before the Special Counsel’s Office of Robert S. Mueller, III (the “SCO”), although Mr. Costello did not specify whether the pertinent appearance was before the grand jury or in some other context; once before the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence; and twice before the U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. See id. Although, in his letter to the Committee and his interview, Mr. Costello said nothing about whether the Defendant was subpoenaed for documents by those authorities and whether the Defendant did produce any, and he did not say whether those other subpoenas or requests were limited to communications with the former President or involved other topics as well, the Defendant and Mr. Costello have asserted, essentially, that the Defendant’s alleged prior compliance demonstrates that he understands the process of navigating executive privilege, illustrates his willingness to comply with subpoenas involving communications with the former President, and rebuts evidence that his total noncompliance with the Committee’s subpoena was willful.

[snip]

The Defendant cannot defend the charges in this case by offering evidence of his experience with and alleged prior compliance with requests or subpoenas for information issued by Congress and the SCO.

[snip]

The Defendant’s alleged prior compliance with subpoenas or requests for information is of no consequence in determining whether he was contemptuous here.

[snip]

Specifically, the Defendant’s alleged compliance with other demands for testimony is not probative of his state of mind in failing to respond to the Committee’s subpoena, and his alleged non-contemptuous character is not an element of the contempt offenses charged in this case.

[snip]

1 1 To the extent the Defendant seeks to introduce evidence of his general character for law-abidingness, see In re Sealed Case, 352 F.3d 409, 412 (D.C. Cir. 2003), he cannot use evidence of his alleged prior subpoena compliance to do so. Evidence of “pertinent traits,” such as law-abidingness, only can be introduced through reputation or opinion testimony, not by evidence of specific acts. See Fed. R. Evid. 404(a)(2)(A); Fed. R. Evid. 405(a); Washington, 106 F.3d at 999.

[snip]

Second, whatever probative value the Defendant’s alleged prior compliance in other circumstances might serve, that value is substantially outweighed by the trial-within-a-trial it will prompt and the confusion it will inevitably cause the jury.

[snip]

The Defendant’s reliance on counsel and/or his alleged good faith in response to prior subpoenas is thus not pertinent to any available defense and is irrelevant to determining whether his failure to produce documents and appear for testimony in response to the Committee’s subpoena was willful. [my emphasis]

The reason DOJ always referred to Bannon’s past compliance with subpoenas as “alleged” is because calling the claim “bullshit” — which is what it is — would be unseemly in a DOJ filing.

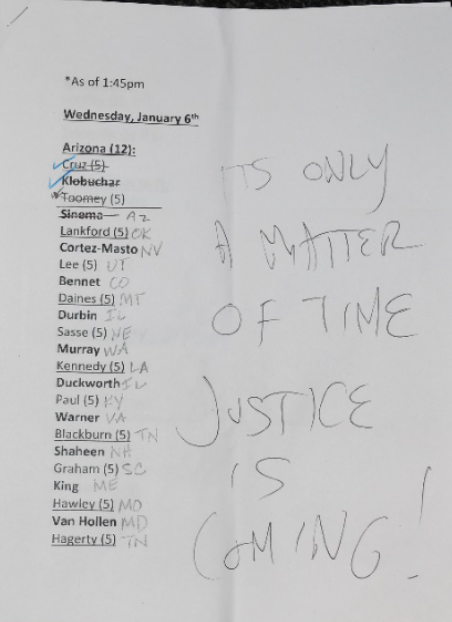

As a reminder, here’s the history of Bannon’s “alleged” past compliance with subpoenas (it is unknown whether he was subpoenaed in the Build the Wall fraud investigation):

HPSCI: Bannon got subpoenaed after running his mouth off in the wake of the release of Fire and Fury (Republicans likely acceded to that so they could discipline Bannon for his brief and soon-aborted effort to distance himself from Trump). In his first appearance, Bannon refused to answer a bunch of questions. Then, in a second appearance and after the intervention of Devin Nunes, Bannon reeled off a bunch of “no” answers that had been scripted by Nunes and the White House, some of which amounted to misdirection and some of which probably were lies. Bannon also claimed that all relevant communications would have been turned over by the campaign, even though evidence submitted in the Roger Stone case showed that Bannon was hiding responsive — and very damning — communications on his personal email and devices.

SSCI: Bannon was referred in June 2019 by the Republican-led committee to DOJ for making false statements to the Committee.

According to the letter, the committee believed Bannon may have lied about his interactions with Erik Prince, a private security contractor; Rick Gerson, a hedge fund manager; and Kirill Dmitriev, the head of a Russian sovereign fund.

All were involved in closely scrutinized meetings in the Seychelles before Trump’s inauguration.

[snip]

No charges were filed in connection with the meetings. But investigators suspected that the men may have been seeking to arrange a clandestine back-channel between the incoming Trump administration and Moscow. It’s unclear from the committee’s letter what Bannon and Prince might have lied about, but he and Prince have told conflicting stories about the Seychelles meeting.

Prince said he returned to the United States and updated Bannon about his conversations; Bannon said that never happened, according to the special counsel’s office.

Mueller: Over the course of a year — starting in two long interviews in February 2018 where Bannon lied with abandon (including about whether any of his personal comms would contain relevant information), followed by an October 2018 interview where Bannon’s testimony came to more closely match the personal communications he had tried to hide, followed by a January 2019 interview prior to a grand jury appearance — Bannon slowly told Mueller a story that more closely approximated the truth — so much so that Roger Stone has been squealing about things Bannon told the grand jury (possibly including about a December 2016 meeting at which Stone appears to have tried to blackmail Trump) ever since. Here’s a post linking Bannon’s known interview records and some backup.

But then the DC US Attorney’s Office (in efforts likely overseen by people JP Cooney, who is an attorney of record on this case) subpoenaed Bannon in advance of the Stone trial, and in a preparatory interview, Bannon reneged on some of his testimony that had implicated Stone. At Stone’s trial, prosecutors used his grand jury transcript to force Bannon to adhere to his most truthful testimony, though he did so begrudgingly.

In other words, the record shows that Bannon has always been contemptuous, unless and until you gather so much evidence against him as to force him to blurt out some truths.

Which is why I find it curious that DOJ moved to exclude Bannon’s past contemptuousness, rather than moving to admit it as 404(b) evidence showing that, as a general rule, Bannon always acts contemptuously. His character, DOJ could have claimed, is one of deceit and contempt. The reason may be the same (that contempt is a one-time act in which only current state of mind matters).

But I’m also mindful of how the Mueller Report explained not prosecuting three people, one of whom is undoubtedly Bannon.

We also considered three other individuals interviewed — [redacted] — but do not address them here because they are involved in aspects of ongoing investigations or active prosecutions to which their statements to this Office may be relevant.

That is, one reason Bannon wasn’t prosecuted for lying to Mueller was because of his import in, at least, the ongoing Roger Stone prosecution. That explains why DOJ didn’t charge him in 2019, to retain the viability of his testimony against Stone. I’m interested in why they continue the same approach. It seems DOJ’s decision to treat Bannon’s past lies — even to SSCI! — as “alleged” rather than “criminally-referred” by SSCI, may also reflect ongoing equities in whatever Bannon told the the grand jury two years ago. One thing Bannon lied about at first, for example, was the back channel to Dubai that may get him named as a co-conspirator in the Tom Barrack prosecution.

But there were other truths that Bannon ultimately told that may make it worthwhile to avoid confirming that those truths only came after a whole bunch of lies.

Update: Thanks to Jason Kint for reminding me that Bannon refused to be served an FTC subpoena pertaining to Cambridge Analytica in 2019.