How Richard Barnett Could Delay Resourcing of the Trump Investigation

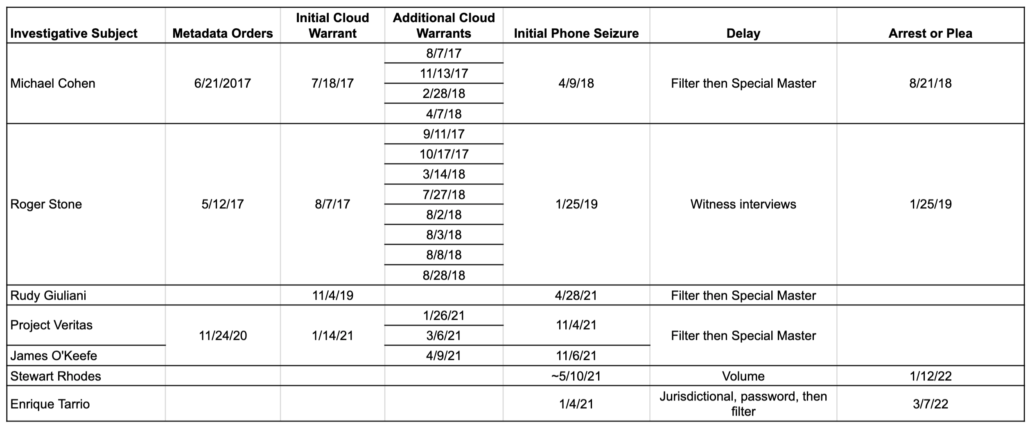

In the rush to have something to say about what Special Counsel Jack Smith will do going forward, the chattering class has glommed onto this letter, signed by US Attorney for Southern Florida Juan Gonzalez under Jack Smith’s name, responding to a letter Jim Trusty sent to the 11th Circuit a day earlier. Trusty had claimed that the Special Master appointed to review the contents of Rudy Giuliani’s phones was a precedent for an instance where a judge used equitable jurisdiction to enjoin an investigation pending review by a Special Master.

The question raised was whether a court has previously asserted equitable jurisdiction to enjoin the government from using seized materials in an investigation pending review by a special master. The answer is yes. The United States agreed to this approach – and the existence of jurisdiction – in In the Matter of Search Warrants Executed on April 28, 2021, No. 21-MC-425-JPO (S.D.N.Y.) (involving property seized from Hon. Rudolph W. Giuliani) – and, under mutual agreement of the parties, no materials were utilized in the investigation until the special master process was completed. 1 See, e.g., Exhibit A. The process worked. On November 14, 2022, the United States filed a letter brief notifying the District Court that criminal charges were not forthcoming and requested the termination of the appointment of the special master. See Exhibit B. On November 16, 2022, the matter was closed. See Exhibit C.

As the government noted, none of what Trusty claimed was true: the government itself had sought a Special Master in Rudy’s case and Judge Paul Oetken had long been assigned the criminal case.

That is incorrect. As plaintiff recognizes, the court did not “enjoin the government,” id.; instead, the government itself volunteered that approach. Moreover, the records there were seized from an attorney’s office, the review was conducted on a rolling basis, and the case did not involve a separate civil proceeding invoking a district court’s anomalous jurisdiction. Cf. In the Matter of Search Warrants Executed on April 9, 2018, No. 18-mj-3161 (S.D.N.Y.) (involving similar circumstances). None of those is true here.

The government could have gone further than it did. The big difference between the Special Master appointed for Rudy and this one is that Aileen Cannon interfered in an ongoing investigation even though there was no cause shown even for a Special Master review, and indeed all the things that would normally be covered by such a review (the attorney-client privileged documents) were handled in the way the government was planning to handle them in the first place.

Josh Gerstein had first pointed to the letter to note that both Gonzalez, the US Attorney, and Smith, the Special Counsel, had submitted a document on Thanksgiving. The claim made by others that this letter showed particular toughness — or that that toughness was a sign of Smith’s approach — was pure silliness. DOJ has been debunking false claims made about the Special Master reviews of Trump’s lawyers since August. That they continue to do so is a continuation of what has gone before, not any new direction from Smith. Indeed, the most interesting thing about the letter, in my opinion, is that a US Attorney signed a letter under the authority of a Special Counsel, the equivalent of a US Attorney in seniority. If anything, it’s a testament that DOJ has not yet decided where such a case would be prosecuted, which would leave the decision to Smith.

A more useful place to look for tea leaves for Jack Smith’s approach going forward is in Mary Dohrmann’s workload — and overnight decisions about it.

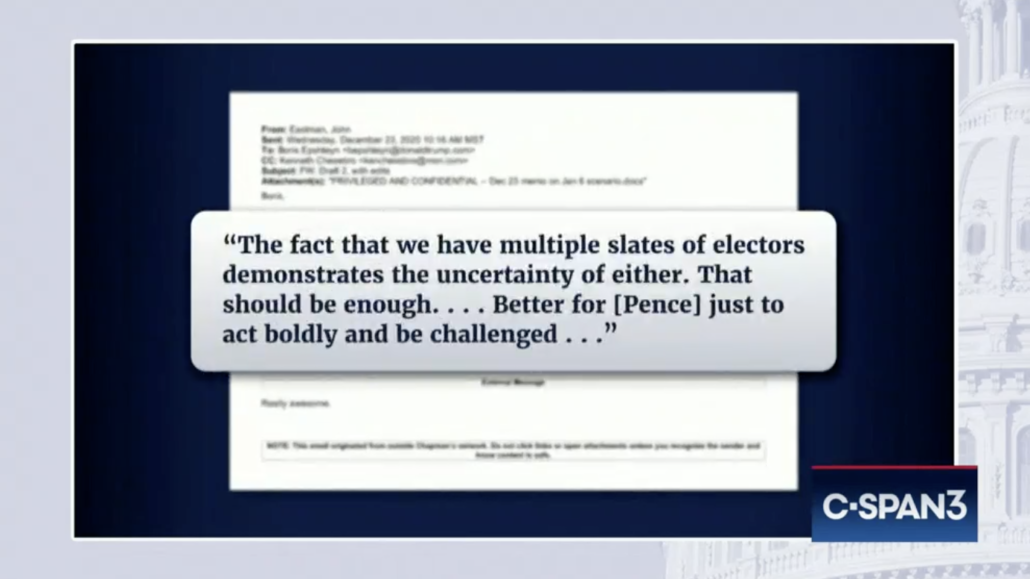

Thomas Windom is the prosecutor usually cited when tracking the multiple strands of investigation into Trump’s culpability for January 6. But at least since the John Eastman warrant in August, Dohrmann has also been overtly involved. She’s been involved even as she continued to work on a bunch of other cases.

With two other prosecutors, for example, she tried Michael Riley, the Capitol Police cop convicted on one count of obstructing the investigation into January 6. In addition to Jacob Hiles (the January 6 defendant tied to Riley’s case), she has prosecuted a range of other January 6 defendants, ranging in apparent levels of import:

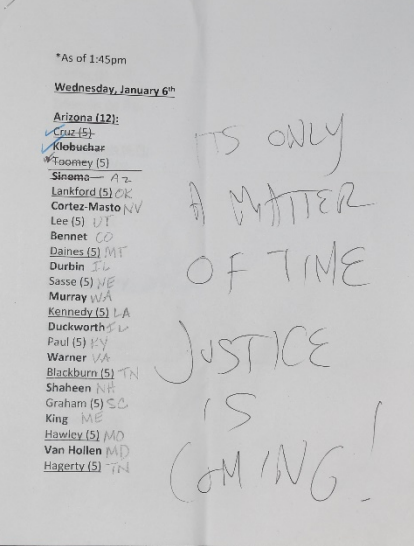

- Richard Barnett, trial for trespassing with a weapon and obstruction scheduled for December 12

- Vaughn Gordon, who pled to parading in September (a new prosecutor was added November 23)

- Jacob Hiles, sentenced for parading in December 2021 (with consideration for cooperation against Michael Riley)

- James Horning, pled to restricted entry in October, sentencing scheduled for January 5 (Dohrmann remains the only prosecutor on the case)

- Matthew Martin, acquitted of trespassing in a Trevor McFadden bench trial in April

- Sean McHugh, awaiting April 2023 trial for multiple counts of assault, civil disorder, obstruction (Dorhmann dropped off the case on November 22)

- Jeffrey McKellop, in plea discussions that may resolve by December 8 for multiple counts of assault and civil disorder, with potential new charges pertaining to allegedly violating the protective order

- Russell Peterson, sentenced for parading last December (Dorhmann dropped off the case in May 2021)

- Alexander Sheppard, awaiting trial for obstruction (two new prosecutors were added on November 4)

- Lori and Thomas Vinson, sentenced for parading in November 2021

- Josh Wagner and Israel Tutrow, sentenced for parading in December 2021 (Dorhmann dropped off the case in August 2021)

She has also been involved in several non-January 6 prosecutions:

- Harold Foreman, weapons possession (Dohrmann dropped off the case in March)

- Zachary Jackson, sentenced for weapons possession (Dorhmann dropped off the case in March, just before sentencing)

- Nekko Callum Johnson, sentenced for weapons possession in January 2022 (Dohrmann dropped off the case in April 2021)

- Winston Kelly, weapons possession (Dohrmann dropped of the case in March)

- Charity Keys, awaiting sentencing for bribery (a new prosecutor joined the case on November 7)

In other words, on the day Smith was appointed, Dorhman was prosecuting several January 6 defendants for trespassing, several for assault, and a cop convicted of obstructing the investigation, even as she was investigating the former President. Though she hasn’t been involved in any of the conspiracy cases, Dohrmann’s view of January 6 must look dramatically different than what you’ll see reported on cable news.

As laid out above, Dorhmann has been juggling cases since January 6; this is typical of the resource allocation that DOJ has had to do on virtually all January 6 cases. That makes it hard to tell when she started handing off cases to free up time for the Trump investigation. That said, there have been more signs she’s handing off cases — both the Vaughn Gordon and Sean McHugh cases — in the days since Smith was named.

But something that happened in the Richard Barnett case revealed how her reassignments on account of Smith’s appointment have been going day-to-day.

Back on November 21 — three days after Garland appointed Jack Smith — Richard Barnett’s attorneys filed a motion asking to delay his trial, currently scheduled for December 12. Their reasons were largely specious. They want to delay until after the DC Circuit decides whether to reverse Carl Nichols’ outlier decision that threw out obstruction charges in the context of January 6; even Nichols hasn’t allowed defendants awaiting that decision to entirely delay their prosecution. They also want to delay in hopes the conspiracy theories that the incoming Republican House majority will chase provide some basis to challenge Barnett’s prosecution.

On November 4, 2022, a Congressional report from members of the House Judiciary Committee released a one thousand page report based on whistleblowers documenting the politicization and anti-conservative bias in the FBI and the Department of Justice. This historic report will no doubt serve as a road map for probes of the agencies now that the Republicans have gained control of the House of Representatives. Included among the many allegations is the recent revelation that the FBI fabricated schemes to entrap American citizens as false flag operations for political purposes. This devastating report was compounded ten days later on November 14, 2022, by revelations that the FBI was involved in infiltrating other groups of January 6th defendants.

As a third reason, Barrnett’s team noted that one of his lawyers, Joseph McBride (who famously said he didn’t “give a shit about being wrong” when floating conspiracy theories about January 6) had to reschedule a medical procedure for the day of the pretrial conference.

Mr. Barnett’s attorney, Mr. Joseph McBride, was scheduled to have a necessary medical procedure on November 17, 2022, but due to unforeseen complication, the procedure could not be performed and must be rescheduled for December 9, 2022, the day of the pretrial conference and a few days before trial.

Per Barnett’s filing, the government objected to the delay.

Counsel for the Government stated that they will oppose this motion, however, they agreed to stay the deadline for Exhibits, due Monday November 21, 2022, until this motion is resolved. The Government also requested that a status conference be scheduled for that purpose.

According to the government response, Barnett’s attorneys first requested this delay on November 17, the day before Smith was appointed. That’s the day Barnett’s team asked the government whether they objected to a delay.

The government has diligently been preparing for trial. Under the Court’s Amended Pretrial Order, the parties were due to exchange exhibit lists on November 21, 2022. ECF No. 63. On November 17, 2022, however, defense counsel Gross contacted the government to state that the defense again wanted to continue the trial. Defense counsel also indicated that the defense was not prepared to exchange exhibit lists on November 21.

By the time the government filed their response on November 22, four days after Smiths’ appointment, DOJ had changed its mind. DOJ still thinks Barnett’s reasons for delay are bullshit (and they are). But the government cited an imminent change in the prosecution team and suggested a trial a month or so out.

As reflected in the Defendant’s motion, the government initially opposed the Defendant’s request for a continuance. Def.’s Mot. at 1. As discussed below, the government maintains that certain of the Defendant’s proffered reasons do not support a continuance of the trial. Nevertheless, the government has considered all the attendant circumstances and no longer opposes the motion. Accordingly, for the reasons set forth below, the government submits that the Defendant’s motion should be granted without a hearing, the trial date vacated, and a status hearing set to discuss new trial dates.

[snip]

Finally, the government notes that while it is diligently preparing for trial, an imminent change in government counsel is anticipated. Thus, given the government’s strong interest in ensuring continuity in its trial team, coupled with the defendant’s lack of readiness, the government, in good faith, will not oppose the defendant’s continuance. Under such unique time constraints, the government therefore requests that the Court vacate the trial date, without need for a hearing, and set a new trial date and extend the remaining pretrial deadlines by 30 to 45 days. [my emphasis]

The judge in the case, Christopher Cooper, ruled on Wednesday that he will only delay the trial if both sides can fit in his schedule. In his order, he mostly trashed the defense excuses. But he noted that the government, too, should have planned prosecutorial changes accordingly.

The Court will reserve judgment on the Defendant’s 88 Motion to Continue the December 12, 2022 trial date pending receipt of a joint notice, to be filed by November 28, 2022, indicating specific dates on which the parties would be available for trial following a brief continuance. If the parties cannot offer a date that also conforms with the Court’s schedule, the Court will deny the motion and proceed with the scheduled trial. The Court finds that none of the reasons advanced in the Defendant’s motion are grounds for a continuance. This case was charged nearly two years ago, one trial date has already been vacated at the defense’s request, and the present date was set over four months ago. Defense counsel, which now number at least three, have had more than ample time to prepare for trial. The defense has not identified any material evidence that it is lacking, either from the government’s voluminous production of both case-specific and global discovery, or from other public sources. Nor is the pendency of the appeal in U.S. v. Miller an impediment to trial. This and other courts have proceeded with numerous January 6th trials involving the charge at issue in Miller. If the Circuit decides the issue in the defense’s favor, then Mr. Barnett will receive the benefit of that ruling. There is no good reason to halt the trial in the meantime. As for any anticipated change in government trial counsel, the government has been aware of the current trial date for months and should have planned accordingly. That said, the Court would be willing to exercise its discretion and grant a brief continuance should a mutually agreeable date be available. The Court notes, however, that it has a busy docket of both January 6th cases and other matters and therefore may not be able to accommodate the parties’ request. [my emphasis]

Unless and until Dorhmann spins off all her other cases, it won’t be clear whether a change in Barnett’s case indicated she expected to focus more time on Trump or that DOJ wanted to create single reporting lines through Smith (or even whether the change in prosecutorial team involved one of several other prosecutors assigned to the case).

Lisa Monaco has been micro-managing the approach to January 6 from the moment she was confirmed in April 2021. Sure, it’s certainly possible that DOJ didn’t make the final decision on whether to appoint a Special Counsel, and if so, whom, until after Trump announced he was running or until after the GOP won the House. Maybe they delayed any resource discussions until after finalizing a pick.

But depending on the reasons why DOJ changed its mind on Barnett’s case, it’s possible that his still-scheduled December 12 trial could delay the time until Smith has his team in place, by several weeks. It’s also possible DOJ will just go to trial, a high profile one that poses some evidentiary complexities, with the two other prosecutors.

As I’ve suggested above, managing the workload created by the January 6 attack has been unbelievably complex, with rolling reassignments among virtually all prosecution teams from the start. Dohrmann’s caseload is of interest only because the mix of cases she has carried range from trespassers to the former President.

But at this moment, as Smith decides how he’ll staff the investigation he is now overseeing, that caseload may create some avoidable complexities and potentially even a short delay, one that could have been avoided.

Update: In a filing not signed by Mary Dohrmann, the two sides offered January 9 as a possible trial date.