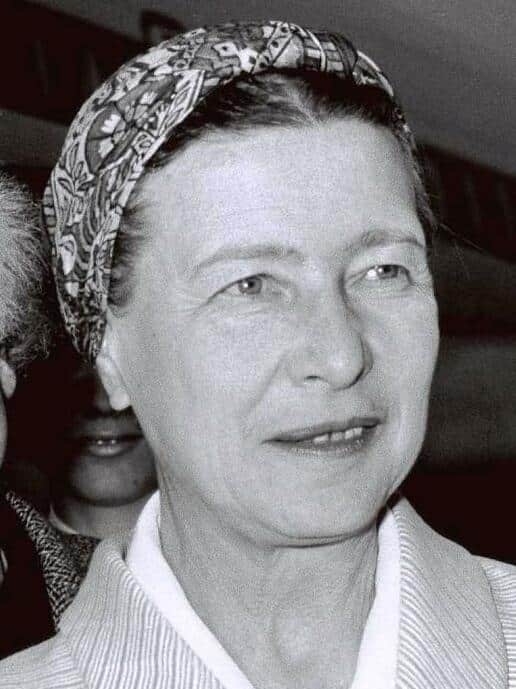

Introduction And Index To The Ethics Of Ambiguity By Simone de Beauvoir

Posts in this series.

Existentialism And Ethics

Coping With Existentialist Ambiguity

More Responses To Existential Ambiguity

Trumpist Moral Choices

My next book is The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir. I was introduced to Existentialism in a required philosophy course my freshman year at Notre Dame. I opted for a course on Christian Existentialism, where I read a good chunk of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. I conceived a very reasonable dislike for him and for the entire project of trying to understand existence through some feat of reason. I was much more impressed with other existentialists, and very much a fan of Albert Camus, who focused on the absurd and ignored Sartre’s formulations of being-in-itself and being-for-itself and other invented words.

But behind the tortured definitions, Existentialists confronted an existence where traditional meanings had been eradicated. The Divine and its representatives on earth, the Church and the clergy, had lost their self-assurance, if not their legitimacy. The humanist replacements offered by 19th and early 20th C. thinkers were proven useless by the rise of totalitarianism. The hole in the soul, the deep emptiness of the void, was a dominant motif across the Western world.

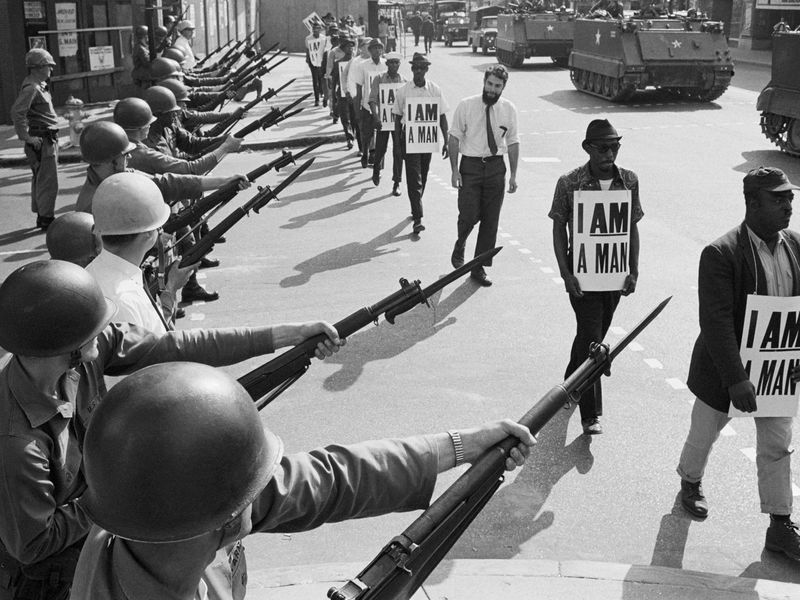

It was a small comfort to me, facing conscription into an army fighting the illegal and immoral Viet Nam War, to see others confronting an ethical horror.

That feeling is back, as we look at the repulsive US government. The kinds of people who joyfully supported the Nazis and the Holocaust surround us today. The people we trusted to manage our institutions turn out to be weaklings, folding in the face of Trump’s bullying. Watching John Roberts and the Fash Five collapse democracy is painful, physically painful. I’m sure scientists and scholars watching the destruction of their life’s work feel the same anguish. Knowing that my family and other families will have to struggle to make sure their kids aren’t tainted by ignorance and immorality is horrifying.

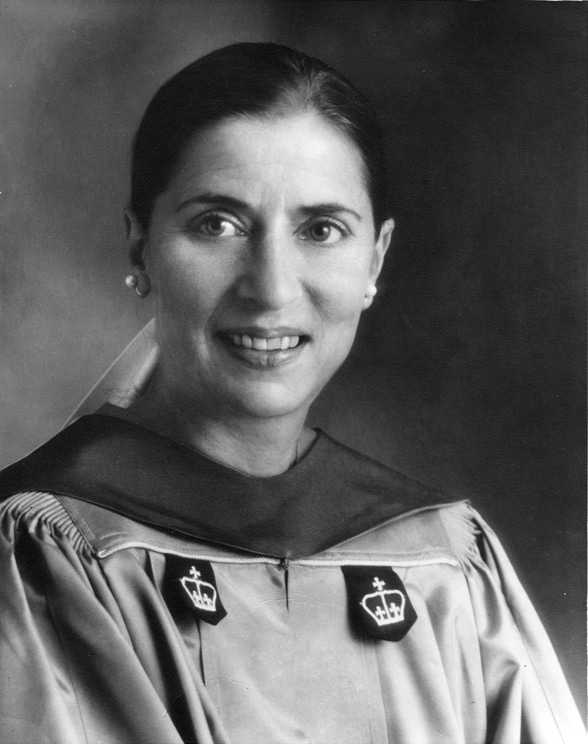

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt gave us a template for the rise of Trump/MAGA. The ideology of neoliberalism, the idea that the only thing that counts is the isolated, atomistic, utterly unconstrained individual, is at the root of the psyche of MAGAs. They believe in the rugged individual epitomized by the Marlboro Man. Their patriarchal religion sanctifies White male domination. Their disdain for expertise and its replacement with crackpots is the same as in Depression-era Germany. With Arendt’s help, we saw it coming but were unable to stop it.

Both Arendt and the Existentialists speak to us today. They don’t have final answers, but they offer a perspective that I think can be helpful, both for protecting ourselves and for preparing for a different future.

Existential Ambiguity

By way of background, I don’t believe there is a systematic explanation for our world. I think we have patches of knowledge that seem useful, that work; and patches of profound ignorance which we can and should acknowledge. We should treat all our “knowledge” as provisional, subject to change. We can’t have a theory of everything, but then, we don’t need one of those. We just need to know enough to survive and flourish.

With that in mind, what does de Beauvoir mean by ambiguity? She (and her translator, in this case Bernard Frechtman) write:

[Man] asserts himself as a pure internality against which no external power can take hold, and he also experiences himself as a thing crushed by the dark weight of other things. … This privilege, which he alone possesses, of being a sovereign and unique subject amidst a universe of objects, is what he shares with all his fellow-men. In turn an object for others, he is nothing more than an individual in the collectivity on which he depends. P. 7, Kindle edition.

This isn’t ambiguity as we use the word, as a state in which one of two things is true but we don’t know which. This is ambiguity in the sense that both things are true but they are, in some way, contradictory. This is like light, which is a wave or a particle, or maybe somehow both at once. It’s a kind of superposition.

We are fully conscious of ourselves. That means we see ourselves as existing in time, and as having a beginning and an end. We believe that our consciousness is a thing special to us, that it is impervious to the outside. But we also see ourselves as being the object of external forces, some helpful, some dangerous. We think we are alone in our subjectivity but we believe we are among other creatures who possess a subjectivity of their own, a subjectivity we cannot fully grasp.

We are both individual subjects for whom other human beings are objects, and we are objects for other individual subjects, both at the same time. That’s the ambiguity de Beauvoir is talking about. We are all Schroedinger’s Cat.

We can say a little more about that subjectivity than de Beauvoir did. First, we think our subjectivity not a fixed thing. It’s attached to our bodies and our experiences, but it changes as both change. And we know for sure that our personal subjectivity is affected by, and often changed by, other subjectivities. This adds another layer to the notion of our belonging to the collective of other human beings.

Ethics

At this point it’s sufficient to say that ethics is the area of philosophy which tries to answer the question of how we should live. That includes, among other things, how we should interact with others in the collective of which we are a part. It raises the question of our duties and obligations to others, and their corresponding duties and obligations to us. If any.

Ethics is usually defined as concerning morality, but that seems too bound to a specific culture. For purposes of this series I think it’s better to think of ethics as being about the shared nature of human beings, and this, I think, is how de Beauvoir addresses the subject.

This book is about ethics in the world Simone de Beauvoir faced:

[A]t every moment, at every opportunity, the truth comes to light, the truth of life and death, of my solitude and my bond with the world, of my freedom and my servitude, of the insignificance and the sovereign importance of each man and all men. There was Stalingrad and there was Buchenwald, and neither of the two wipes out the other. Since we do not succeed in fleeing it, let us therefore try to look the truth in the face. Let us try to assume our fundamental ambiguity. It is in the knowledge of the genuine conditions of our life that we must draw our strength to live and our reason for acting. P. 9