Steve Bannon Employee Lee Stranahan Purportedly Convinced Roger Stone to Love Guccifer 2.0

As I’ve been laying out, there are discrepancies between what Steve Bannon told the FBI in his second interview on February 14, 2018 and the fragments of his grand jury appearance on January 18, 2019 revealed during his testimony at the Roger Stone trial on November 8, 2019. (His first interview on February 12, 2018 contains similar convenient forgetfulness, and his second on October 26, 2018 remains unavailable; he reportedly had a trial prep interview where he backtracked on some of what he had said under penalty of perjury in early 2019.)

Bannon and the campaign were more interested in WikiLeaks than he initially let on.

Bannon tried to hide his role and knowledge of Stone’s back channel to WikiLeaks

While the 302s currently redact Stone’s name, in his first interview, Bannon claimed — after a discussion of the email about WikiLeaks that Don Jr forwarded to others on the campaign — that he didn’t remember anyone else in contact with WikiLeaks, and didn’t remember anyone reaching out to Stone.

Bannon did not remember anyone else in contact with WikiLeaks or trying to get in contact with WikiLeaks. There was discussion during the campaign on how WikiLeaks would impact the race. Bannon did not think anyone had any ideas on where WikiLeaks had got their information. Bannon did not remember anyone reaching out to [redaction, probably Stone], WikiLeaks, or any other intermediary to see what information might be coming.

In the grand jury testimony that prosecutors made him hew to during the trial, however, Bannon admitted that the campaign understood that Stone was the access point, if one were pursued, to WikiLeaks.

Q. Now, I want you to turn to page 14, line 4. I’m going to read line 4 through 8 on page 14. And you’re asked, “And just within the campaign, who was the access point to WikiLeaks?”

And you responded, “I think it was generally believed that the access point or potential access point to WikiLeaks and to Julian Assange would be Roger Stone.”

Did I read that correctly?

A. That’s correct.

Q. And did you, at that time, did you personally believe or you personally view Roger Stone as the access point between Trump campaign and WikiLeaks?

A. Yes.

Bannon likely first began to admit this in October 2018, when prosecutors showed him the email reflecting Bannon emailing Stone (via his non-campaign email) on October 4, 2016 to ask why WikiLeaks hadn’t dumped anything on that day, as predicted. Bannon seemed less squirmy about admitting that at Stone’s trial.

Q. Why then, why did you send this email then, that date on October 4th, 2016, to Mr. Stone?

A. I don’t believe — I think the press conference was about another topic or it wasn’t about the topic that everybody had hyped it about.

Q. Was one of the reasons why you sent this email to Mr. Stone because he was the access point to WikiLeaks and Julian Assange in the campaign?

A. Yes, he had a relationship or told me he had a relationship with Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, so it would be natural that I would reach out to him.

Q. So were you sending this email to try to find out why there wasn’t any announcement that day?

A. I think it’s twofold. One is to find out why there’s no announcement, and the other was a little bit of a heckle.

But at the trial, Bannon was also squirmy about admitting the timing of his knowledge that Stone claimed to have a back channel to WikiLeaks.

Q. So you were asked at page 7, line 15, “And when you had private conversations with him about his connection to Julian Assange, approximately how far in advance of your joining the campaign did that conversation take place?”

And you responded, “Oh, I think the first time it was months before, but I think it all the way led up to right before I joined the campaign. It was something he would, I think, frequently mention or talk about when we talked about other things.”

Did I read that correctly?

A. That’s correct.

Q. All right. Now, in any of your conversations with Mr. Stone, did he ever brag to you about his connections to Assange?

A. I wouldn’t call it bragging, but maybe boasting, I guess the difference between bragging and boasting, but he would mention it.

Q. What do you mean by “boast”?

A. That he had a relationship with WikiLeaks and Julian Assange.

On its face, that’s damning because it puts Stone’s claimed awareness of WikiLeaks’ plans back to around June 2016, when (according to trial evidence) Stone was calling Trump just as Guccifer 2.0 started dropping emails on June 14, 2016 and also calling Rick Gates to get Jared Kushner’s email so they could strategize the release.

Q. Did you know why Mr. Stone was asking you for Mr. Kushner’s contact information at that time?

A. Mr. Stone indicated that he wanted to reach out to Mr. Kushner and Mr. Murphy to debrief them on the developments of the DNC announcement.

I’ve come to realize that that line from Bannon — “it all the way led up to right before I joined the campaign” — is actually more damning. That’s because of the role of Lee Stranahan in this story. I also suspect Bannon is a key player in what I suspect is Roger Stone’s use of stolen emails in his social media campaigns sowing racial division.

When I’ve thought of the dumps of stolen emails in the past, I’ve thought of the DNC emails, the DCCC emails about state races, and the Podesta emails.

Then Breitbart reporter Lee Stranahan’s outreach to Guccifer 2.0 coincided with Stone’s efforts to learn what WikiLeaks had coming

But as the GRU indictment reminds (in a paragraph that immediately precedes the one discussing Roger Stone’s interactions with Guccifer 2.0), the persona also gave then Breitbart journalist Lee Stranahan access to some documents on Black Lives Matter over a week before releasing them publicly.

On or about August 22, 2016, the Conspirators, posing as Guccifer 2.0, sent a reporter stolen documents pertaining to the Black Lives Matter movement. The reporter responded by discussing when to release the documents and offering to write an article about their release.

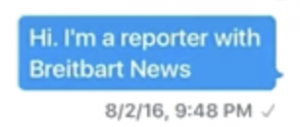

What is believed to be the entirety of Stranahan’s exchanges with Guccifer 2.0 appear here. The first of those DMs is one from August 2, 2016, where Stranahan introduces himself.

In the wake of the Roger Stone trial, the date is more interesting. Days earlier, Stone had ratcheted up his efforts to learn — and possibly get — the emails that would soon be dumped, with key emails with Jerome Corsi on July 25 and 31, and Corsi’s response hours earlier on August 2 to Stone promising Podesta emails. There are also calls from Stone to Gates (on July 31). Stone wrote Manafort on July 29 promising “Good shit happening.” In the wake of Corsi’s email about Podesta emails, Stone had calls with Trump on on August 2, and a text to Gates reporting as much. Then the next day, after Stranahan had introduced himself to get no response, Stone wrote Manafort boasting he had “an idea to save Trump’s ass.”

The Breitbart column that led Stone to interact with Guccifer 2.0

Days later (and after Stone claimed to Sam Nunberg that he had dined with Julian Assange on August 3), Stone wrote a column in Breitbart — still under the direction of Steve Bannon — claiming that Guccifer 2.0 was the lone culprit behind the DNC hack, not Russia.

I have some news for Hillary and Democrats—I think I’ve got the real culprit. It doesn’t seem to be the Russians that hacked the DNC, but instead a hacker who goes by the name of Guccifer 2.0. The original Guccifer famously hacked Hillary’s home email server, you might remember.

[snpi]

Then Guccifer 2.0 even did an interview going into detail about how they had done the hacking and tried to get some media traction but the media wasn’t biting. Someone from The Hill did a piece, but that was about it. For some strange reason, the establishment press didn’t want to take on the establishment Democrat machine.

[snip]

Inspiration stuck: ignore Guccifer 2.0. The DNC being hacked by one person didn’t look sinister enough. Time for the victim card! Blame the Russians! Blame Putin! Blame Trump!

No, it didn’t make any sense. Yes, the evidence about Guccifer 2.0 was already out there. But it’s good to the be the Queen.

Now, common sense would inform most sane people that if Russia were dong what Hillary says they were doing they simply would have gone straight to Wikileaks. However, common sense didn’t fit Hillary’s narrative and so the press went all in with her fable.

Bannon now admits, when pressed to adhere to his sworn grand jury testimony, that in precisely this period he and Stone remained in discussions about his back channel to WikiLeaks.

The Breitbart column became the public impetus for Stone and Guccifer 2.0’s own exchanges over the weekend of August 12. At 10:23PM, Guccifer 2.0 tweeted publicly to Stone, “Thanks that u believe in the real #Guccifer2,” a reference to that Breitbart post. At 11:40 ET (I believe Stranahan was in Idaho at the time, but these DMs appear to be printed out on ET), Stranahan DMed Guccifer 2.0 taking credit for convincing Stone that Guccifer 2.0 was not Russian.

But Guccifer 2.0 didn’t respond to Stranahan right away. Instead, over the weekend, Stone Tweeted that “Gruccifer is a HERO.” The next day, Stone complained that Guccifer 2.0 had been banned by Twitter (technically he did so after Guccifer had been reinstated, if indeed he was actually banned). Then, sometime that same day, Stone DMed Guccifer 2.0 and told the persona he was “Delighted you are reinstated.”

At 1:33AM on August 15, Stone tweeted about John Podesta for the first time ever. “@JohnPodesta makes @PaulManafort look like St. Thomas Aquinas Where is the @NewYorkTimes ?” Sometime on August 15, Guccifer 2.0 DMed Stone, “thank u for writing back, and thank u for an article about me!! . . . do u find anyting interesting in the docs I posted?” Stone responded, asking Guccifer to RT a story on how the election could be hacked. Guccifer followed up with more platitudes on August 17.

All the while, Stone kept bragging publicly that he had a back channel to WikiLeaks.

Steve Bannon consults with the Mercers before joining the Trump campaign

Even as that was happening, Steve Bannon was consulting with his bosses about whether he should go save the Trump campaign. Before he joined the campaign, someone he consulted (given the reference to an anti-Hillary Super PAC and the timing of the June meeting, this is almost certainly the Mercers, then the owners of both Breitbart and part owners of Cambridge Analytica) worried about Breitbart being blamed if Trump lost.

Bannon had read a NYTimes article describing the Trump campaign being in disarray, so he started to make a few phone calls. At the time, Trump was 12-16 points down, there was talk of the Republican National Committee (RNC) cutting Trump loose, and the Republicans were distancing themselves from Trump for fear of losing control of the House of Representatives. Bannon called [redacted] and there was worries that if Bannon became involved in the Trump campaign, Breitbart could be blamed if Trump lost. Bannon had previously talked to [redacted] back in June 2016 in an effort for them to make peace with Trump.

Ultimately, he joined the campaign at a time — he says over and over again in his interviews that have been made public — the campaign was badly underwater in the polls and broke.

Bannon was hired on August 14, but it became public on August 17, then Paul Manafort resigned on August 19.

Who did what with social media on August 18?

At 1:02 AM on the morning of August 18, Stone wrote Bannon at his arc-ent email.

Trump can still win –but time is running out.

Early voting begins in six weeks.

I do know how to win this but it ain’t pretty.

Campaign has never been good at playing the new media.

Lots to do–let me know when u can talk.

R

Bannon replied at 6:14 AM: “Let’s talk ASAP.”

In my opinion, this is the most puzzling public email from the entire Mueller investigation. That’s because the date and content seems to be the subject of a different DOJ investigation, about which Manafort at first provided details, seemingly implicating Kushner, and then reneged, seemingly blaming it all on Stone. The email to Bannon makes it clear this is about “new media” — the social media we’ve heard so much about, where the Trump campaign hired Cambridge Analytica which led to a social media strategy that purportedly found new Republican voters and suppressed black turnout. It’s possible that’s what the other DOJ investigation was into, as references to Cambridge Analytica in Bannon’s 302 are redacted under an ongoing investigation redaction.

Indeed, when Bannon was first asked about such things (indeed, about joining the campaign), Bannon said Kushner — the guy that Manafort implicated — was “in charge of the digital campaign.”

In August 2016, Kushner was in charge of the digital campaign and fundraising. Bannon was the CFO of the campaign with Jeff DeWitt. The campaign had almost no cash and they were receiving only a small amount from cash contributions. The campaign was losing cash at the time and they were down by a double digit lead with the 1st debate coming. They needed $50 million from Trump, which eventually became $10 million.

The reference within the 302 was out of context, but it seems that Bannon offered up that at a time when the campaign was broke and underwater, the candidate’s son-in-law embraced a strategy that turned things around.

Remarkably, prosecutors at Stone’s trial didn’t get Bannon to explain precisely what this email meant — aside from suggesting that he agreed there was a tie to WikiLeaks and used a bunch of nice words to explain this had to do with Stone’s rat-fucking.

Q. When Mr. Stone wrote to you, “I do know how to win but it ain’t pretty,” what in your mind did you understand that to mean?

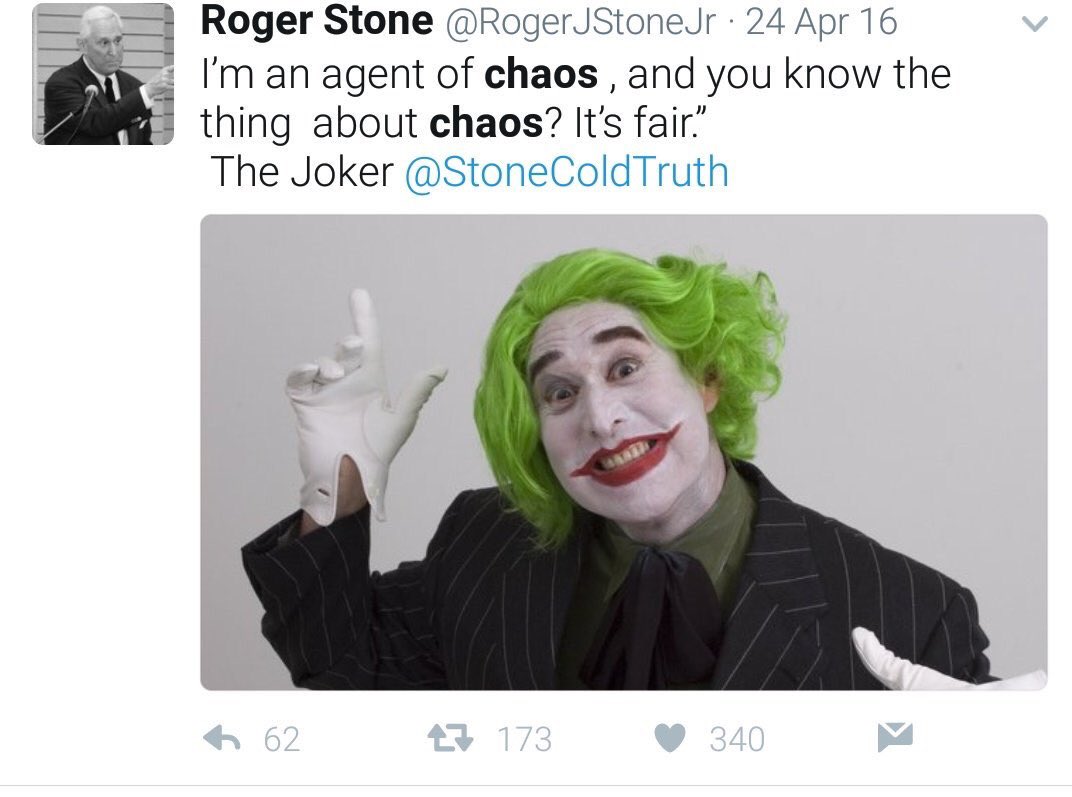

A. Well, roger is an agent provocateur, he’s an expert in opposition research. He’s an expert in the tougher side of politics. And when you’re this far behind, you have to use every tool in the toolbox.

Q. What do you mean by that?

A. Well, opposition research, dirty tricks, the types of things that campaigns use when they have got to make up some ground.

Q. Did you view that as sort of value added that Mr. Stone could add to the campaign?

A. Potentially value added, yes.

Q. Was one of the ways that Mr. Stone could add value to the campaign his relationship with WikiLeaks or Julian Assange?

A. I don’t know if I thought it at the time, but he could — you know, I was led to believe that he had a relationship withWikiLeaks and Julian Assange.

Rather than getting Bannon to explain what this email was about in more detail, they instead moved to talk about the October 4 email where Bannon asked about why WikiLeaks had not yet dropped the promised October surprise.

Likewise, prosecutors did not ask Bannon what Stone meant by the end of that October 4 email, where Stone demanded Bannon get Bannon to give him money for his own digital campaign.

I know your surrogates are dumb but try to get them to understand the Danney Williams case

chick mangled it on CNN this am

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3819671/Man-claiming-Bill-Clinton-s-illegitimate-son-prostitute-continues-campaign-former-president-recognize-him.html

I’ve raise $150L for the targeted black digital campaign thru a C-4

Tell Rebecca to send us some $$$

On August 18, Stone complained about the campaign’s paltry new media campaign. On October 4, Stone demanded Bannon help him raise money for a digital campaign. It’s unclear what the modifier “black” refers to, but in the context of Stone’s focus on Danney Williams — a black man that Stone was focusing on to suggest Bill Clinton had a secret child of a prostitute — suggests the digital campaign was about sowing division based on race (not coincidentally, the same strategy the IRA’s trolls were using).

In fact, Stone had started that campaign at least as earlier as October 16, 2015 (when he first tweeted about Williams), and he continued it persistently through the campaign. At times, he tied it to an effort to source the Black Lives Matter movement on Hillary, which Stone also used Hillary’s record in Haiti and Libya to do.

Incidentally, that demand for money from the chair of the campaign probably amounts to illegal coordination, as would Stone’s repeated demand from Rick Gates for voter lists, which was also revealed at the trial.

Stranahan obtains files pertinent to Stone’s social media focus

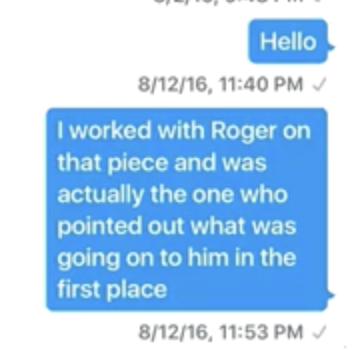

On 9:24 AM on August 21, Stone tweeted the “time in the barrel” tweet that first raised questions about his foreknowledge that WikiLeaks would release the John Podesta emails. Almost 12 hours alter, Guccifer 2.0 finally responded to Stranahan’s DMs. Guccifer offers Stranahan “exclusive files,” as the persona had for journalists and a Republican Florida lobbyist.

They DM back and forth for an hour and a half, after which Guccifer says he’s sending “some exclusive files” to Stranahan’s Gmail. Guccifer makes sure to get Stranahan to confirm he has received them. Stranahan almost immediately focuses on a Black Lives Matter “thing,” something that Breitbart had been stoking just as long as Stone had been stoking the Danney Williams thing.

The next day, Guccifer gets Stranahan to confirm that the Black Lives Matter documents are important. The go back and forth about what the optimal timing for their release is. On August 30 at 10:41AM, Guccifer asks Stranahan, “how about doing it today?”

An hour and a half later, at 12:17 PM, Stone tweets, “BLACK LIVES MATTER- unless you are in Libya in which case @HillaryClinton bombs you,” a lead up to his efforts to get stolen emails on Libby from WikiLeaks via Credico in the following weeks. Sometime that afternoon, Stone emails Corsi asking him to call; Stone would ask Corsi to create a cover story for their discussions of Podesta earlier that month, which he did in one day.

At 4:03, Guccifer DMs Stranahan and offers to release the Black Lives Matter file at any particular time. But ultimately, Guccifer publishes the file — purporting that it came from Pelosi’s computer — on August 31, without getting Stranahan’s advance okay.

There’s no reason to believe Stone was in the loop with Stranahan on this, particularly given their dramatically different response to the next exchange. On September 9, the same day Guccifer floats the DCCC turnout models to Florida that Stone judges are “Pretty standard” to Guccifer, Stranahan says that “it’s great” but adds he’s “having trouble with my company right now so let me figure out the right way to break this.”

Stranahan would go on to quit Breitbart — in part because they wouldn’t let him attend White House press briefings to pester Sean Spicer about Crowdstrike hoaxes — and move to his own radio show at Sputnik.

But it was not just Stranahan at Breitbart that remained in the loop of Stone’s focus on WikiLeaks. Before Bannon emailed Stone about WikiLeaks on October 4, Breitbart’s Matthew Boyle exchanged emails with Stone. He asked Stone what Assange had, Stone implied he knew and complained that “Bannon … doesn’t call me back.” Boyle forwarded the email to Bannon and told him he “should call Roger.” Which Bannon tried to brush off by saying he had “important stuff to worry about.”

Yet he did write Stone (the context of that earlier exchange did not come up at Stone’s trial). And Stone came right back and asked for money for his “black digital campaign.”

I don’t know what to make of all this. But Stone’s actions with respect to Guccifer 2.0 look far more damning when viewed in parallel with Stranahan’s actions.

Curiously, even in spite of his mention in the GRU indictment, that incident doesn’t appear to be mentioned even in the redacted passages of the Mueller Report, as Stranahan doesn’t appear in the glossary at all.

Which may suggest his import had more to do with the August 2 column, written with Stone for Bannon, than his ongoing exchanges with Guccifer 2.0.