Bill Barr Issued Prosecution Declinations for Three Crimes in Progress

On March 24, 2019, by judging that there was not evidence in Volume II of the Mueller Report that Trump had obstructed justice, Billy Barr pre-authorized the obstruction of justice that would be completed with future pardons of Mike Flynn, Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone. He did so before the sentencing of Flynn and before even the trial of Stone.

This is why Amy Berman Jackson should not stay her decision to release the Barr Memo. It’s why the question before her goes well beyond the question of whether the Barr memo presents privileged advice. What Barr did on March 24, 2019 was pre-authorize the commission of crimes that ended up being committed. No Attorney General has the authority to do that.

As the partially unsealed memo makes clear, Steve Engel (who, even per DOJ’s own filing asking for a stay, was not permitted to make prosecutorial decisions) and Ed O’Callaghan (who under the OLC memo prohibiting the indictment of the President, could not make prosecutorial decisions about the President) advised Bill Barr that he should, “examine the Report to determine whether prosecution would be appropriate given the evidence recounted in the Special Counsel’s Report, the underlying law, and traditional principles of federal prosecution.”

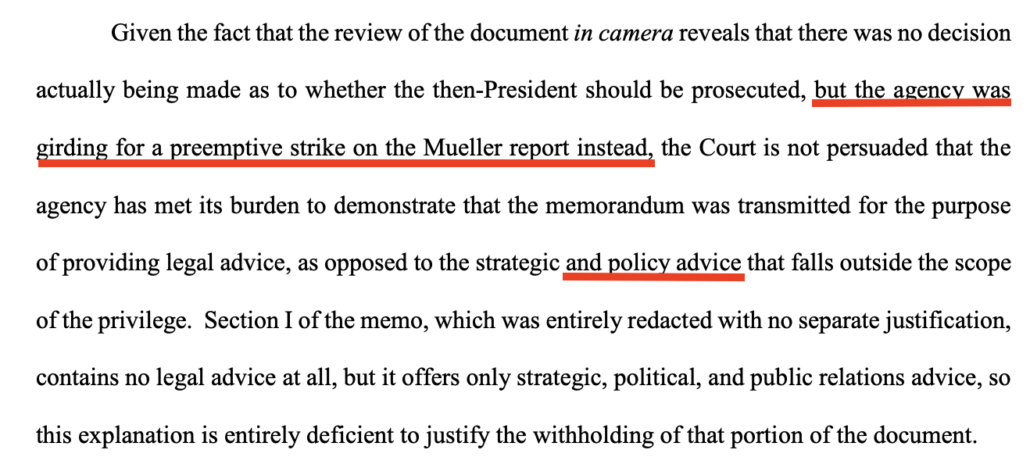

In her now-unsealed memo ordering the government to release the memo, ABJ argues, “the analysis set forth in the memo was expressly understood to be entirely hypothetical.”

It was worse than that.

It was, necessarily, an instance of “Heads Trump wins, Tails rule of law loses.” As the memo itself notes, the entire exercise was designed to avoid, “the unfairness of levying an accusation against the President without bringing criminal charges.” It did not envision the possibility that their analysis would determine that Trump might have committed obstruction of justice. So predictably, the result of the analysis was that Trump didn’t commit a crime. “[W]ere there no constitutional barrier, we would recommend, under Principles of Federal Prosecution, that you decline to commence such a prosecution.”

The government is now appealing ABJ’s decision to release the memo to hide the logic of how Engel and O’Callaghan got to that decision. And it’s possible they want to hide their analysis simply because they believe that, liberated from the entire “Heads Trump wins, Tails rule of law loses” premise of the memo, it becomes true deliberative advice (never mind that both Engel and O’Callaghan were playing roles that OLC prohibits them to play).

But somehow, in eight pages of secret analysis, Engel and O’Callaghan decide — invoking the entire Special Counsel’s Report by reference — that there’s not evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump obstructed justice.

We can assume what some of these eight pages say. In the newly unsealed parts, Engel and O’Callaghan opine, “that certain of the conduct examined by the Special Counsel could not, as a matter of law, support an obstruction charge under the circumstances.”

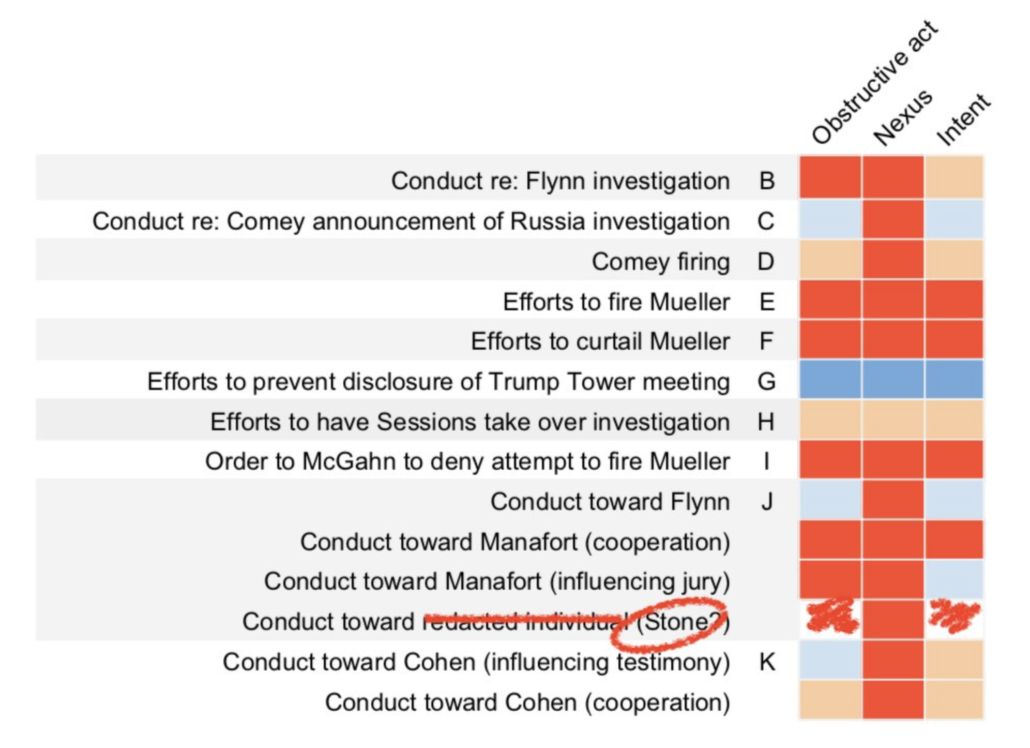

As Quinta Jurecic’s epic chart lays out, the potential instances of obstruction of justice before Engel and O’Callaghan included a number of things involving Presidential hiring and firing decisions — the stuff which the memo Bill Barr wrote as an audition for the job of Attorney General said could not be obstruction.

To address those instances of suspected obstruction, then, Engel and O’Callaghan might just say, “What you said, Boss, in the memo you used to audition to get this job.” That would be scandalous for a whole bunch of reasons — partly because Barr admitted he didn’t know anything about the investigation when he wrote the memo (even after the release of the report, Barr’s public statements made it clear he was grossly unfamiliar with the content of it) and partly because it would raise questions about whether by hiring Barr Trump obstructed justice.

But that’s not actually the most scandalous bit about what must lie behind the remaining redactions. As Jurecic’s chart notes, beyond the hiring and firing obstruction, the Mueller Report laid out several instances of possible pardon dangles: to Mike Flynn, to Paul Manafort, to Roger Stone, and to Michael Cohen. These are all actions that, in his confirmation hearing, Barr admitted might be crimes.

Leahy: Do you believe a president could lawfully issue a pardon in exchange for the recipient’s promise to not incriminate him?

Barr: No, that would be a crime.

Even Barr admits the question of pardon dangles requires specific analysis.

Klobuchar: You wrote on page one that a President persuading a person to commit perjury would be obstruction. Is that right?

Barr: [Pause] Yes. Any person who persuades another —

Klobuchar: Okay. You also said that a President or any person convincing a witness to change testimony would be obstruction. Is that right?

Barr: Yes.

Klobuchar: And on page two, you said that a President deliberately impairing the integrity or availability of evidence would be an obstruction. Is that correct?

Barr: Yes.

Klobuchar: OK. And so what if a President told a witness not to cooperate with an investigation or hinted at a pardon?

Barr: I’d have to now the specifics facts, I’d have to know the specific facts.

Yet somehow, in eight pages of analysis, Engel and O’Callaghan laid out “the specific facts” that undermined any case against Trump for those pardon dangles. I’d be surprised if they managed to do that convincingly in fewer than eight pages, particularly since they make clear that they simply assume you’ve read the Mueller Report (meaning, that analysis almost certainly doesn’t engage in the specific factual analysis that Bill Barr says you’d need to engage in).

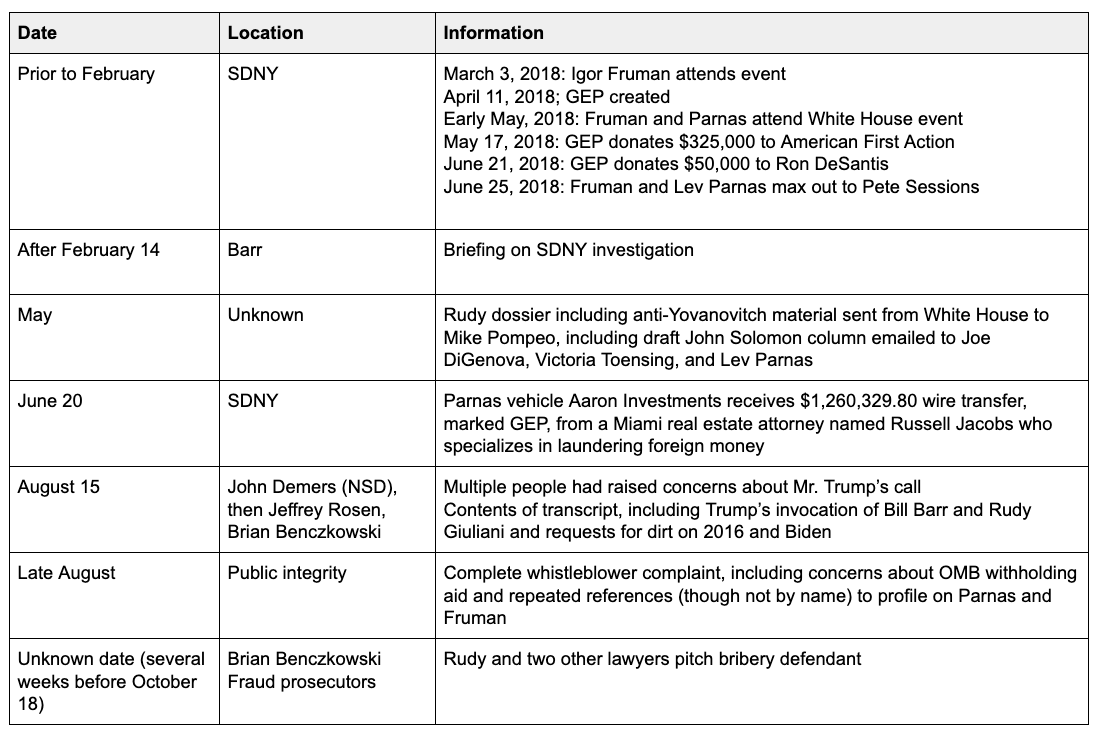

The far, far more problematic aspect of this analysis, though, is that, of the four potential instances of pardon dangles included in the Mueller Report, three remained crimes-in-progress on March 24, 2019 when Barr issued a statement declining prosecution for them.

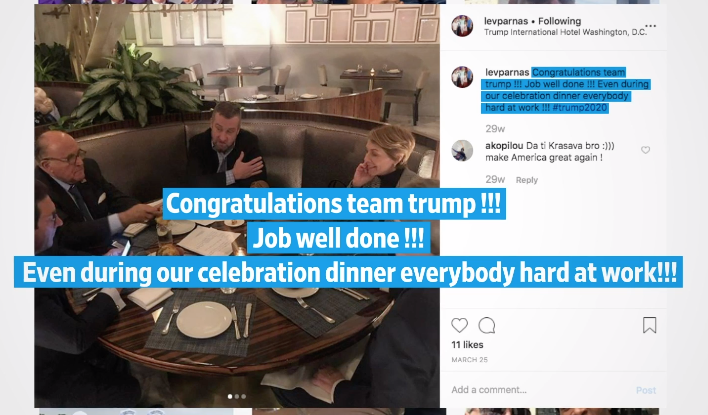

By then, Michael Cohen had already pled guilty and testified against Trump. But Paul Manafort had only just been sentenced after having reneged on a cooperation agreement by telling lies to hide what the government has now confirmed involved providing assistance (either knowing or unknowing) to the Russia election operation. Mike Flynn had not yet been sentenced — and in fact would go on to renege on his plea agreement and tell new lies about his conduct, including that when he testified to the FBI that he knew he discussed sanctions, he didn’t deliberately lie. And Roger Stone hadn’t even been tried yet when Barr said Stone’s lies to protect Trump weren’t a response to Trump’s pardon dangles. In fact, if you believe Roger Stone (and I don’t, in part because his dates don’t line up), after the date when Barr issued a declination statement covering Trump’s efforts to buy Stone’s silence, prosecutors told him,

that if I would really remember certain phone conversations I had with candidate trump, if I would come clean, if I would confess, that they might be willing to, you know, recommend leniency to the judge perhaps I wouldn’t even serve any jail time

If that’s remotely true, Barr’s decision to decline prosecution for the pardon dangles that led Stone to sustain an obviously false cover story through his trial itself contributed to the obstruction.

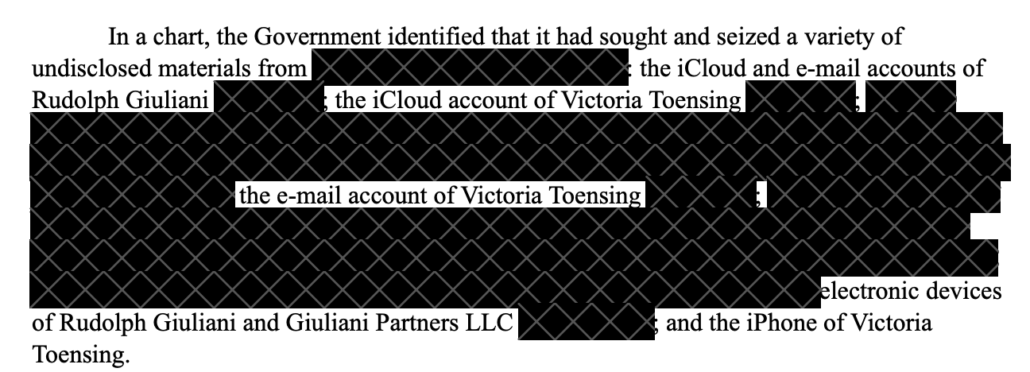

Barr’s decision to decline prosecution for obstruction crimes that were still in progress may explain his even more outrageous behavior after that. For each of these remaining crimes in progress, Barr took steps to make it less likely that Trump would issue a pardon. He used COVID as an excuse to spring Paul Manafort from prison to home confinement, even though there were no cases of COVID in Manafort’s prison at the time. He engaged in unprecedented interference in the sentencing process for Roger Stone, even going so far as claiming that threats of violence against (as it happens) Amy Berman Jackson were just a technicality not worthy of a sentencing enhancement. And Bill Barr’s DOJ literally altered documents in their effort to invent some reason to blow up the prosecution of Mike Flynn.

And Barr may have realized all this would be a problem.

On June 4, a status report explained that DOJ was in the process of releasing the initially heavily redacted version of this memo to CREW and expected that it would be able to do so by June 17, 2020, but that “unanticipated events outside of OIP’s control” might delay that.

However, OIP notes that processing of the referred record requires consultation with several offices within DOJ, and that unanticipated events outside of OIP’s control may occur in these offices that could delay OIP’s response. Accordingly, OIP respectfully submits that it cannot definitively guarantee that production will be completed by June 17, 2020. However, OIP will make its best efforts to provide CREW with a response regarding the referred record on or before June 17, 2020

This consultation would have occurred after Judge Emmet Sullivan balked at DOJ’s demand that he dismiss the Flynn prosecution, while the DC Circuit was reviewing the issue. And it occurred in the period when Stone was using increasingly explicit threats against Donald Trump to successfully win a commutation of his sentence from Trump (the commutation occurred weeks after DOJ gave CREW a version of the memo that hid the scheme Barr had engaged in). That is, DOJ was making decisions about this FOIA lawsuit even as Barr was taking more and more outrageous steps to try to minimize prison time — and therefore the likelihood of a Trump pardon — for these three. And Trump was completing the act of obstruction of justice that Barr long ago gave him immunity for by commuting Stone’s sentence.

Indeed, Trump would go on to complete the quid pro quo, a pardon in exchange for lies about Russia, for all three men. Trump would go on to commit a crime that Barr already declined prosecution for years earlier.

While Barr might believe that Trump’s pardon for Mike Flynn was righteous (even while it undermined any possibility of holding Flynn accountable for being a secret agent of Turkey), there is no rational argument you can make that Trump’s pardon of Manafort after he reneged on his plea deal and Trump’s pardon of Stone after explicit threats to cooperate with prosecutors weren’t obstruction of justice.

This may influence DOJ’s decision not to release this memo, and in ways that we can’t fathom. There are multiple possibilities. First, this may be an attempt to prevent DOJ’s Inspector General from seeing this memo. At least the Manafort prison assignment and the Stone prosecution were investigated and may still be under investigation by DOJ. If Michael Horowitz discovered that Barr took these actions after approving of a broad pre-declination for pardon-related obstruction, it could change the outcome of any ongoing investigation.

It may be an effort to stave off pressure to open a criminal investigation by DOJ into Barr’s own actions, a precedent no Attorney General wants to set.

Or, it may just be an effort to hide how many of DOJ’s own rules DOJ broke in this process.

But one thing is clear, and should be clearer to ABJ than it would be to any other judge: Bill Barr issued a prosecution declination for three crimes that were still in process. And that’s what DOJ is hiding.