In a post laying out what I called my “taxonomy” of the DOJ investigation of the January 6 crime scene, I noted that the next step in holding those who orchestrated January 6 responsible was to start holding the “organizer-inciters” responsible.

I have argued that DOJ is very close to rolling out more details of the plot to seize the Capitol, a plot that was implemented (at the Capitol) by the Proud Boys in coordination with other militia-tied people. I have also argued that one goal of the misdemeanor arrests has been to obtain evidence showing that speeches inciting violence, attacks on Mike Pence, or directing crowds to (in effect) trespass brought about violence, the targeting of Mike Pence, and the breach of the Capitol.

If I’m right about these two observations, it means that the investigation has reached a step where the next logical move would be to charge those who incited violence or directed certain movement. The next logical step would be to hold those who caused the obstruction accountable for the obstruction they cultivated.

This is why I focused on Alex Jones in this post: because there is a great deal of evidence that Alex Jones, the guy whom Trump personally ordered to lead mobs to the Capitol, was part of the plot led by his former employee, Joe Biggs, to breach a second front of the Capitol. If this investigation is going to move further, people like Alex Jones and other people who helped organize and incite the riot, will be the next step.

Though you might not know it from the coverage, DOJ has charged several people who played a key role in creating and mobilizing the mob that seized the Capitol. This is where, however, the obscurity of the investigation and First Amendment protections raise real questions about whether DOJ will be able to move up the chain of responsibility.

I’d like to look at the prospects of accountability at three nodes of organizer inciters:

- Walkaway founder Brandon Straka

- SoCal anti-maskers Russell Taylor and Alan Hostetter

- Alex Jones, Owen Shroyer, and Ali Alexander

The import of January 5 in January 6

Before I do so, though, a word about January 5. Though the general outline of the January 6 attack kicked off in November 2020 and was fine-tuned in December (the MAGA events in both months were critical both as dry runs and for networking among participants), the final outline of plans took place in the days before the riot. There seems to have been an intra-militia meeting planned on January 3 in Quarrysville, Pennsylvania where groups, “[got] our comms on point with multiple other patriot groups.”

After Proud Boy Enrique Tarrio got arrested on January 4, the Proud Boys frantically tried to regroup. As late as 9PM on January 5, Joe Biggs and Ethan Nordean were meeting with some unnamed group, out of which came their plan for the 6th.

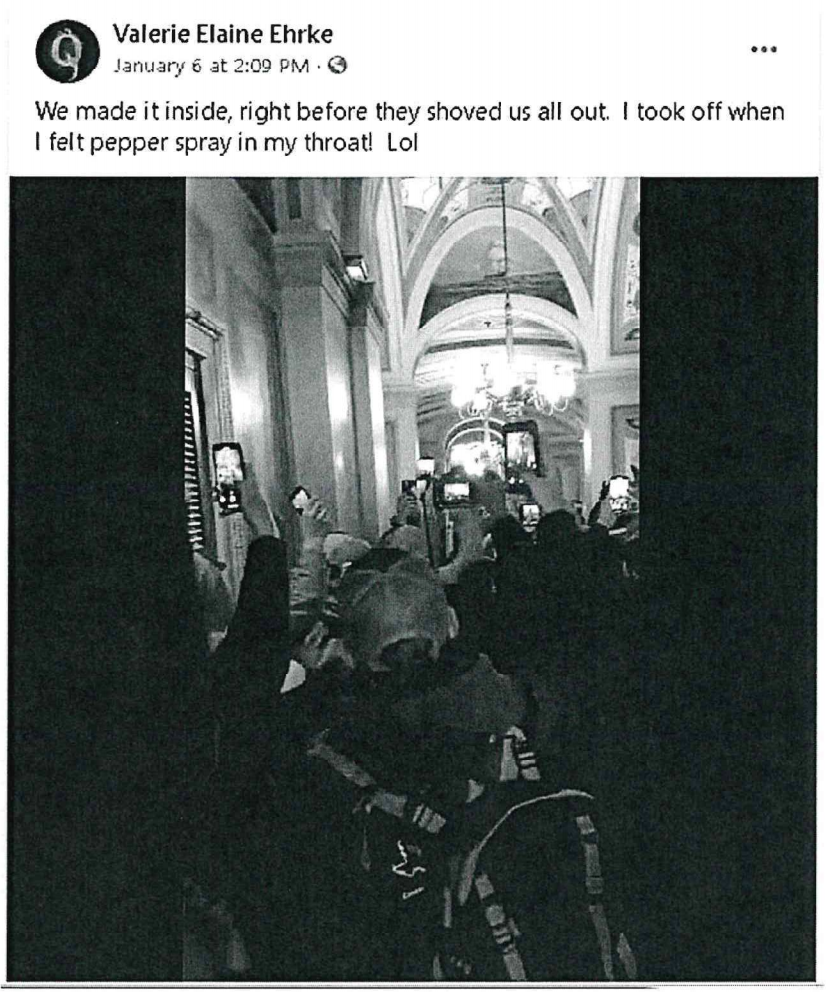

There were rallies organized for January 5 at which a number of leaders gave incendiary speeches. There’s some reason to believe that members of what I’ve called a “disorganized militia” conspiracy, Ronnie Sandlin, Nate DeGrave, and Josiah Colt, learned key details of the plan for the next day at that event, which allowed them to be tactically important in the breach. Other disorganized attendees, like Jenny Cudd, came away from those Janaury 5 speeches persuaded a revolution was inevitable.

On January 5, 2021, Ms. Cudd stated the following in a video on social media: “a lot of . . . the speakers this evening were calling for a revolution. Now I don’t know what y’all think about a revolution, but I’m all for it. . . . Nobody actually wants war, nobody wants bloodshed, but the government works for us and unfortunately it appears that they have forgotten that, quite a lot. So, if a revolution is what it takes then so be it. Um, I don’t know if that is going to kick off tomorrow or not, we shall see what the powers that be choose to do with their powers and we shall see what it is that happens in Congress tomorrow at our United States Capitol. So, um either way I think that either our side or the other side is going to start a revolution.”

As Robert Costa and Bob Woodward have described, Trump ratcheted up the pressure as the mobs formed the night of January 5 by falsely claiming that Mike Pence agreed he could ignore the true vote counts.

Yet, even in spite of the import of January 5 to what happened on January 6, DOJ has included remarkably few details about what January 6 defendants did that day.

The organizer-inciters called for revolution on January 5

The three organizer-inciters are a notable exception. As I noted in this post, DOJ focused on the January 5 speeches of Straka, Shroyer, and Taylor in their arrest affidavits. Straka’s described how he called for revolution on January 5.

STRAKA was introduced by name and brought onto stage. STRAKA spoke for about five minutes during which time he repeatedly referred to the attendees as “Patriots” and referenced the “revolution” multiple times. STRAKA told the attendees to “fight back” and ended by saying, “We are sending a message to the Democrats, we are not going away, you’ve got a problem!”

The SoCal 3%er conspiracy described how Russell Taylor called for violence.

[T]hese anti-Americans have made the fatal mistake, and they have brought out the Patriot’s fury onto these streets and they did so without knowing that we will not return to our peaceful way of life until this election is made right, our freedoms are restored, and American is preserved.

And Owen Shroyer’s arrest affidavit described him calling for revolution, too.

Americans are ready to fight. We’re not exactly sure what that’s going to look like perhaps in a couple of weeks if we can’t stop this certification of the fraudulent election . . . we are the new revolution! We are going to restore and we are going to save the republic!

But the treatment of these three organizer-inciters, both in their charges, and the development of their prosecution so far, has been very different.

Brandon Straka

Originally, Brandon Straka was charged with trespassing and 18 USC 231, civil disorder, for egging on rioters as they stripped a cop of his shield.

At around the 3:45 mark of the video, an officer from the United States Capitol Police holding a protective shield could be seen in the crowd. As individuals pushed past the officer toward the entrance of the U.S. Capitol, the officer held his shield up in the air. At around the 3:59 mark of the video, STRAKA stated, “Take it away from him.” STRAKA and others in the crowd then yelled, “Take the shield!”

As several people in the crowd grabbed the officer’s shield, STRAKA yelled, “Take it! Take it!” The crowd successfully pulled the shield away from the officer as the officer appeared to be trying to move back toward the entrance of the building.

After his early arrest, his case was continued without indictment several times, first in February, then in May, then in August, each time invoking fairly standard boilerplate about a plea. “The government and counsel for the defendant have conferred, and are continuing to communicate in an effort to resolve this matter.” In September, Straka was finally charged, with just the less serious of the two trespassing misdemeanors. After a tweak in October reflecting that he never entered the Capitol itself, he pled guilty on October 6. His statement of offense says only this about January 5:

Brandon Straka flew to Washington D.C. to speak at a rally protesting the election results on January 5 and January 6, 2021.

It focuses entirely on his role in egging on rioters at the Capitol.

This plea could be one of the ones in which someone cooperating was able to plead to a misdemeanor (the only confirmed one of which, so far, was Jacob Hiles, who cooperated in the prosecution of Michael Riley). After all, he could provide valuable information not just on the plans for January 5, but also explain what he learned about why the scheduled rally on January 6, at which he was also supposed to speak, got canceled. And in fact, he posted the kind of self-justification in advance of pleading that might reflect cooperation.

[O]n Facebook this week he addressed 357,000 followers as “Dear Patriots,” thanked them for their patience, and urged them to tune out “negative press . . . likely coming down the pike” as he took the first meaningful step toward concluding “the perils of the situation I am in.”

“Hang on tight,” Straka wrote on the site, where he has asked for financial support and plugged a forthcoming “grand relaunch” of his campaign. “Let it come, and let it go. It means nothing. It’s just pointless noise. The best is yet to come. We’re almost there.”

But his plea agreement includes the boilerplate cooperation language that generally gets taken out when someone has already cooperated, which is one reason to believe his plea may just reflect good lawyering.

We may find out whether his plea included a cooperation component when we see the filings regarding his sentencing. He was originally supposed to be sentenced on Friday December 17, but that got bumped back (as many things are, these days) to December 22. His sentencing memos were due on December 15. But unless something happened with PACER overnight, they’re not there (PACER was particularly unreliable yesterday on account of the AWS outage, but the filings could also be sealed).

Update: The two sides have asked for 30 more days to make sense of some stuff that has recently come up.

On December 8, 2021, the defendant provided counsel for the government with information that may impact the government’s sentencing recommendation. Additionally, the government is requesting additional time to investigate information provided in the Final Pre- Sentence Report. Because the government’s sentencing recommendation may be impacted based on the newly discovered information, the government and defendant request a 30-day continuance of this case so that the information can be properly evaluated.

The government is currently ordered to file its sentencing memorandum and any video evidence in support of its memorandum on December 17, 2021. The government respectfully requests that this deadline be extended based upon the reasons stated.

3%er SoCal Conspiracy

Calling the indictment against Alan Hostetter et al the “3%er SoCal conspiracy” is actually a misnomer, because it has more to do with how two men calling for violence helped organize Southern Californians largely mobilized around anti-mask politics.

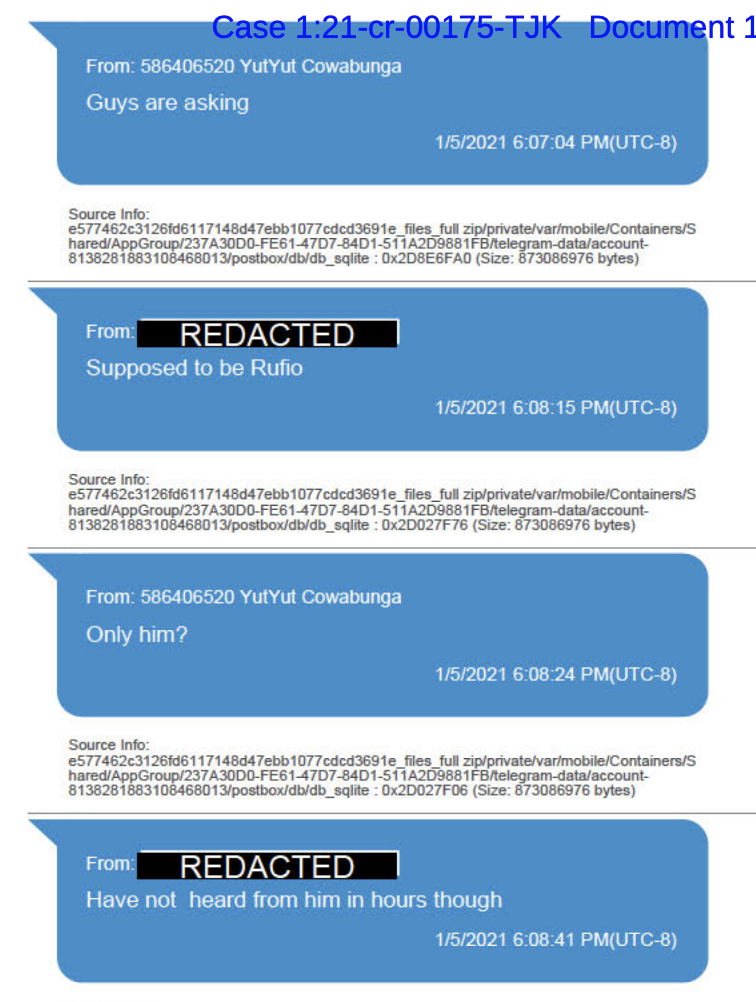

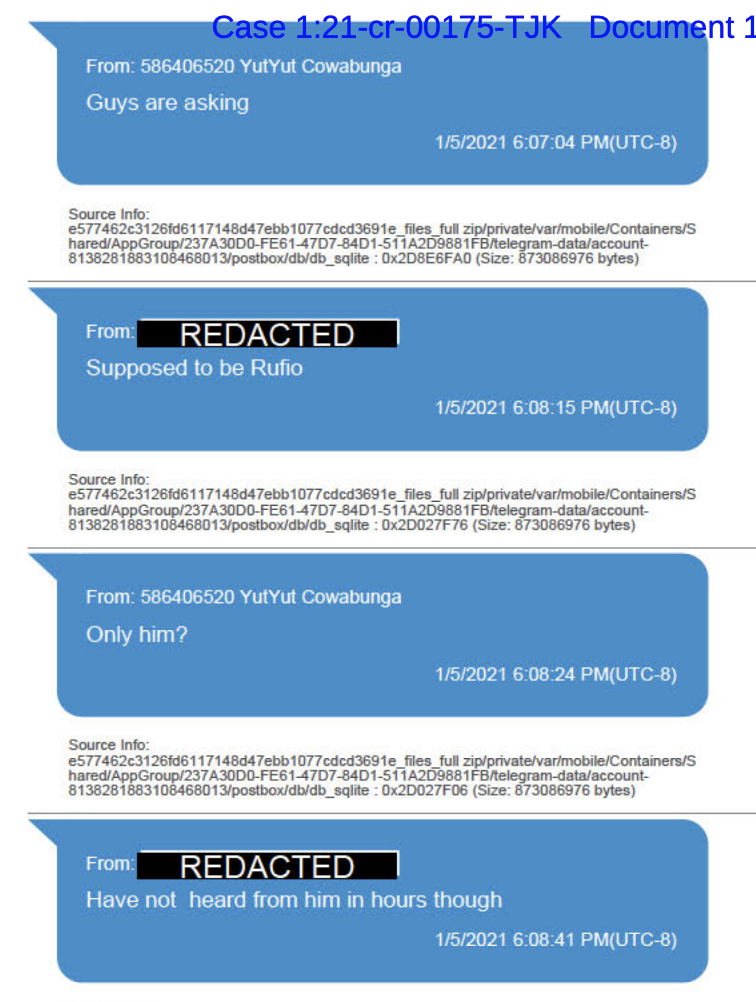

The indictment provides evidence that some of the men charged–Erik Warner, Tony Martinez, Derek Kinnison, and possibly Ronald Mele– are 3%ers. Though the indictment shows Hostetter invoking the language of 3%ers in one place, he is the head of the American Phoenix anti-mask group and his anti-mask activism is one of the places Hostetter met Russell Taylor (the other is the QAnon conference in Arizona in October 2020). Hostetter and Taylor repurporsed a Telegram chat Hostetter was already using to sow violence to organize Southern Californians to travel to DC for the rally, then created a new one on January 1 called “The California Patriots-DC Brigade.”

Much of the conspiracy involves the planning of alleged conspirators for the trip, including discussions of how to bring weapons to DC.

Just one of these men, Warner, entered the Capitol; the rest skirmished around the West Terrace. Not all of the January 6 defendants whose arrest documents show them to be members of the California Patriots-DC Brigade Telegram chat are included as part of this conspiracy; Jeffrey Scott Brown and Ben Martin, who were each charged individually, are described to have been part of the chat, and it’s likely that Gina Bisignano and Danny Rodriguez and his co-conspirators were also part of that chat (among others). In addition, there’s a Person One described in the indictment, whom Hostetter has identified as big GOP donor Morton Irvine Smith, who wasn’t charged, though Irvine Smith’s actions appear distinguishable from Hostetter’s only in that he didn’t climb onto the West Terrace on January 6. So it’s not entirely clear why DOJ included the six people they did in this conspiracy.

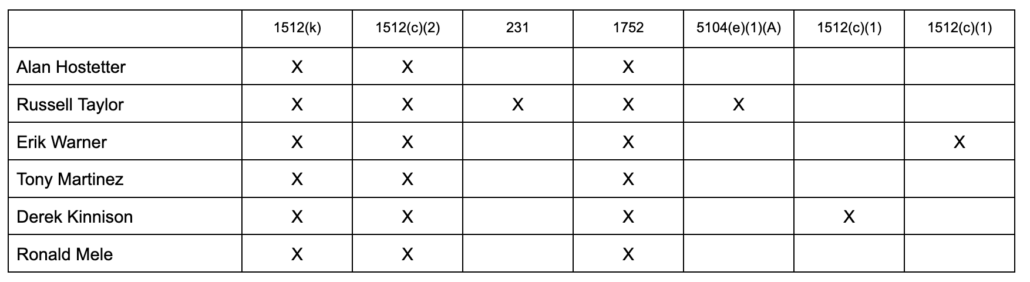

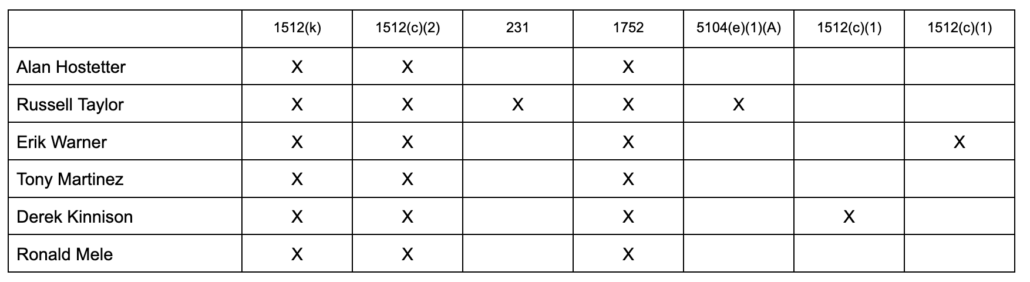

As I laid out before, in addition to being charged individually with obstructing the vote count, the men were charged with conspiracy under the obstruction statute rather than the conspiracy statute, as most other January 6 conspiracies were charged (though a Patriot-3%er two person conspiracy unsealed the other day uses 1512(k) as well). Taylor was charged for civil disorder for an interaction with cops and his trespassing charges were enhanced because he was armed with a knife. Warner and Kinnison are separately charged for efforts to hide the Telegram chat.

In other words, this conspiracy ties together two guys publicly calling for violence with members of a militia who discussed arming themselves.

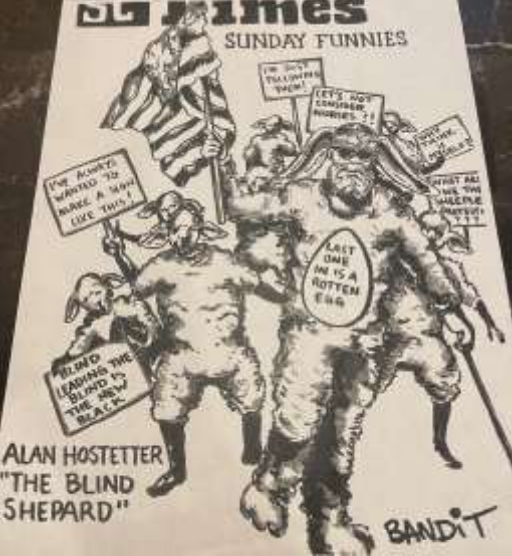

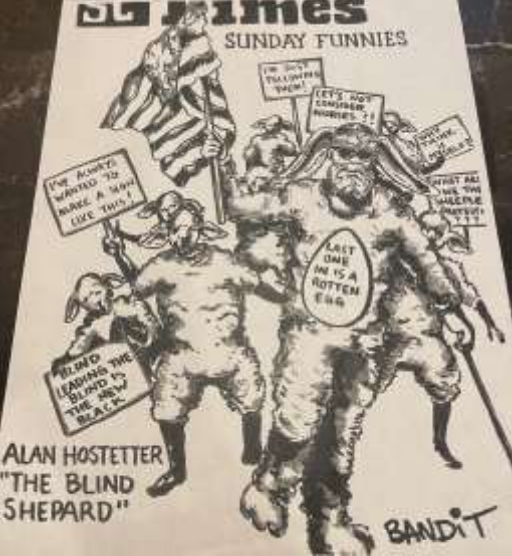

Hostetter says he wants no part of it, though. After getting permission to represent himself in October, earlier this month the former cop filed a motion to dismiss the entire indictment because of alleged government misconduct. The entire thing is the kind of batshit conspiracy theory you’d expect from Tucker Carlson or Glenn Greenwald, spinning what appears to have been inappropriate coddling of him by an Orange County Sheriff’s Sergeant into an FBI plot (that started in spring 2020) to get him, involving Yale’s Secret Society Skull and Bones, the Freemasons, Scientologists, Mormons, and a talented artist named Bandit who likes to mock him. (Read this thread if you want to laugh along.) In the wild yarn Hostetter spins, he argues both Irvine Smith and Taylor must be FBI informants and therefore he can’t be held accountable for any of the actions they induced him to take.

He asks to be severed from the other defendants and/or have his case thrown out because, he claims, he “has never knowingly met, nor has he ever knowingly communicated with, four of the co-defendants,” the 3%ers, and according to his feverish conspiracy theory, Taylor is an FBI informant who set him up (Taylor is Mormon, which is where that part of Hostetter’s conspiracy theory stems from). In a filing asserting as fact that, “the election of 2020 was actually stolen from a duly elected President whom was elected in one of the biggest landslide victories in the history of our country,” Hostetter complains that his actions to prevent the vote count of the actual winner do not amount to a crime.

On January 6, 2021 defendant did not commit one act of violence. Defendant did not commit one act of vandalism. Defendant never entered the U.S. Capitol Building. Defendant never conspired with anyone to do anything illegal, immoral or unethical. The government has not provided anything, that defendant has yet seen in discovery, that contradicts these claims by defendant. Yet, defendant is charged with federal felonies that could result in his imprisonment for up to twenty years.

Particularly given the scope of Dabney Friedrich’s ruling on the application of obstruction, with its caveats regarding whether legal activities can be deemed part of an effort to obstruct the vote count, Hostetter’s claims may have some success (Royce Lamberth is presiding over the case).

His motion to dismiss doesn’t, however, mention a number of overt acts described in the conspiracy to obstruct the vote count:

- His participation in the November 14, 2020 MAGA event in DC

- His own November 27, 2020 call to execute “traitors”

- A December 12, 2020 Stop the Steal rally in Huntington Beach

- His own calls for people to travel to DC starting on December 19, 2020

Rather than addressing most of the overt acts alleged against him, Hostetter provides what appear to be cover stories for two key December 2020 events in this timeline.

After Taylor and Hostetter spoke at an Orange County event on December 15, they met with Irvine Smith the next day, and Taylor gave both axes.

On December 15, 2020, defendant and co-defendant Russell Taylor both spoke at an Orange County Board of Supervisor’s Meeting. This was only three weeks prior to January 6th. As usual at the Board Meeting, the topics to be discussed related to Orange County issues to include Covid-19 related issues, which is what we typically spoke out about. For some reason, while Taylor was speaking during this particular board meeting, he made the following comment to the Board which was completely unrelated to any of the topics on the agenda: “Week after week, I and others are with thousands in the street all up and down the state of California. You know what they are saying? Revolution. Storm the Capitol.”

[snip]

On December 16th, the day following Taylor’s comments to the Orange County Board of Supervisors, co-defendant Russell Taylor met defendant and “Person One” Morton Irvine Smith at a Mexican restaurant in San Clemente, CA called “El Ranchito.” Taylor was the organizer of this meeting and had requested, planned and organized it a few days prior. While at the restaurant, Taylor told defendant and Irvine Smith that he had purchased gifts for them. Taylor reached under the table and pulled out two boxes and gave them to defendant and Irvine Smith.

Inside these boxes were the axes that have been referred to in the indictment as proof of defendant’s nefarious intent to attack the Capitol using the axe as a weapon of some sort. Until receiving this “gift,” defendant had never personally owned an axe in his life. As he gifted it to us, Taylor described the axe metaphorically as a “battle axe” representing the battles we had already fought in support of freedom and the many battles yet to come.

Upon leaving the restaurant, either (informant) Taylor or (informant) Irvine Smith requested one of the restaurant employees take our photograph in front of the restaurant holding the axes. Defendant liked the photograph and thought it looked quite masculine and “tough” so he posted the photograph to Instagram with a somewhat provocative comment attached to the photograph. Defendant’s comment was, “The time has come when good people may have to act badly, but not wrongly.” Defendant continued in this post with, “Thank you @russ.taylor for the gift of the #thebattleaxe representing the many battles yet to come.”

Defendant had read this quote about good people possibly having to act “badly but not wrongly” in a meme very close in time to when Taylor gifted the axe to him. Defendant had no thought whatsoever about January 6 or the U.S. Capitol when creating this Instagram post. Defendant had been making public speeches regarding the fact that the U.S. was and had been “at war” with the Chinese Communist Party and domestic enemies for approximately 8 months prior to receiving this axe from Russell Taylor

Hostetter posted the photo not as a call for war, he claims, but because it made him look manly. And his caption to the photograph wasn’t a prospective call to war on January 6 in response to Taylor’s call for revolution, but to the prior 8 months of political unrest.

Particularly given Hostetter’s description of the December 16 meeting, which he helpfully tells us was actually planned, “a few days prior” (and so possibly the same day that Irvine Smith, but not Hostetter, returned from the DC MAGA March), I find the description Hostetter gives for his involvement in the January 5 event of interest. He learned of it from Irvine Smith at around the same time as that same December 16 meeting at El Ranchito and before — the indictment alleges but Hostetter ignores — he started recruiting people to attend the event.

January 5, 2021: Defendant’s non-profit organization, American Phoenix Project (APP), cohosted a rally with a group called Virgina Women for Trump. The VWT group was headed by Alice Butler-Short, a well-known and well-connected woman in the DC area.

This event, and APP’s ability to co-host it was brought to defendant’s attention in mid-December after informant Morton Irvine Smith returned to California after attending the December 12, 2020 Stop the Steal rally in Washington DC. Defendant did not attend this event. Irvine Smith claimed to have met Ms. Butler-Short for the first time at this 12/12/2020 event and the two of them agreed to APP becoming involved in co-hosting the event together.

Irvine Smith arranged for defendant to participate in a conference call with Ms. Butler-Short and two members of another group identified as Jericho March as they were a nationally known group also supporting election integrity. Once this conference call was completed, defendant told Irvine Smith that he was not interested in having American Phoenix Project co-host the event as it was too far away from California to be able to properly assist in putting it together and defendant had also gotten a bad vibe / feeling from some of the other participants in the conference call.

Irvine Smith was highly disappointed and notified defendant that he, Irvine Smith, would then just continue to help Butler-Short on his own time as they had developed a good relationship and he wanted to be personally helpful to her. Within a week or two, Irvine Smith notified defendant that Butler-Short had lined up some very big-name and popular conservative speakers for the event to include Roger Stone, Alex Jones, General Michael Flynn’s brother Joe Flynn, among several others. Irvine Smith notified defendant that ButlerShort was continuing to hold out the invitation for APP to co-host this event with her group, to include flying the APP banner at the event. Irvine Smith told defendant the only thing Butler-Short requested of APP was to help her with finding security staff to cordon off an area in front of the Supreme Court because it was a “first come, first served” policy as far as finding a location to set up a stage and microphone.

[snip]

After hearing from Irvine Smith about the high-quality speakers involved and the relative ease with which APP could co-host such a high-profile event, defendant agreed to co-host the event under the APP banner. Were it not for the individual efforts of Morton Irvine Smith, neither defendant nor APP would have been involved with this event at all.

Irvine Smith’s role in getting him this gig certainly raises more questions about why he wasn’t charged, but it doesn’t change Hostetter’s own exposure.

Hostetter adds to the questions about Irvine Smith’s treatment by revealing that Irvine Smith was not searched until the day before this indictment (Hostetter also makes much of what appears to be FBI’s choice to image Irvine Smith’s devices rather than seizing them).

On 1/27/2021 when Taylor and defendant had search warrants served on them, Irvine Smith did not. It wasn’t until nearly five months later, on June 9, 2021 that Irvine Smith finally had a search warrant served on him. This was one day before defendant’s indictment was unsealed. The timing of Irvine Smith’s “raid” is transparently obvious and laughable. It was intended to “clean him up” as an informant.

Hostetter’s questions about Irvine Smith, who funded much of his actions, are as justified as questions from the Oath Keepers about Stewart Rhodes not being charged yet. But I expect this crazypants motion to be dismissed and the conspiracy prosecution to continue to hang on whether all six members of the conspiracy entered into an agreement to help stop the vote count on January 6.

But Hostetter’s motion does suggest that the conspiracy indictment uses the involvement of the 3%ers as a way to raise the stakes of both Hostetter and Taylor’s own public calls for violence. That is, DOJ seems to have charged these organizer-inciters (but not the guy funding it all, yet) by exploiting their ties to an organized militia.

Alex Jones, Owen Shroyer, and Ali Alexander

The way that DOJ appears to have used militia ties to charge organizer-inciters Alan Hostetter and Russell Taylor makes their treatment of far more important organizer-inciters, Alex Jones, Owen Shroyer, and Ali Alexander, more interesting.

Ignore for a moment Ali Alexander’s crucial role in setting up explicitly violent protests.

It is a fact that the guy leading the coup, Donald Trump, asked Alex Jones (personally, as Jones tells it) to lead the mobs Trump had incited at the Ellipse down the Mall to the Capitol. As Jones was doing this, his former employee, Joe Biggs, was kicking off the entire riot. It is also a fact that Jones lured rioters like Stacie Getsinger to the East side of the building, to where Biggs and the Oath Keepers were also gathering, by promising a second speech from Trump.

There’s reason to believe that Jones and Biggs remained in contact that day, evidence of which DOJ would presumably have from Biggs’ phone, if not his phone provider (based on whether the contact was via telephony or messaging app). If it was the latter, getting it may have taken a while. While DOJ obtained Ethan Nordean’s phone when they searched his house (because his spouse provided the FBI the password), and obtained the content of Biggs’ Google account quickly (which included some videos shared with his co-travellers), it may have taken until July 14 to exploit Biggs’ phone (this Cellebrite report must pertain to Biggs because it is not designated Highly Sensitive to him). While the content of any calls Biggs had with his former boss would not be captured, some of it is also likely available from videos shot of him. If his co-travellers wanted a cooperation deal they might be able to provide Biggs’ side of any contacts with Jones too, though several of Biggs’ co-travelers are represented by John Pierce, who may be serving as a kind of firewall for Biggs or even Enrique Tarrio.

Nevertheless, if DOJ has in its possession evidence that one of the guys accused of masterminding the plan to breach the Capitol from two sides was in contact during that process with Jones, who lured unwitting rioters to the second breach by lying to them, then DOJ would appear to have far more evidence tying Jones to militia violence than they used to charge Hostetter in a conspiracy with 3%ers. And Jones got just as far inside the restricted area of the Capitol — to the top of the steps on the East side — as Hostetter did.

Of course, two things have made it harder to charge Jones: he is a media figure, one who very quickly disseminated a cover story claiming his intent for joining the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers at the site of the second breach was to de-escalate the situation, not to escalate it.

DOJ has been chipping away at both those defenses. It already arrested two of Jones’ employees, videographer Sam Montoya and on-air personality Owen Shroyer.

DOJ arrested Montoya for trespassing on April 13 and charged him with misdemeanors on April 30. The arrest warrant cited a number of things Montoya said that were captured on his own footage making it clear he viewed himself as part of the mob.

We’re gonna crawl, we’re gonna climb. We’re gonna do whatever it takes, we’re gonna do whatever it takes to MAGA. Here we go, y’all. Here we go, y’all. Look at this, look at this. I don’t even know what’s going on right now. I don’t wanna get shot, I’ll be honest, but I don’t wanna lose my country. And that’s more important to me than—than getting shot.

And DOJ noted that Montoya had no press credentials for Congress (a really shitty distinction for an event where legitimate journalists chased mobsters inside).

At times during the video, Montoya describes himself to others inside the Capitol Building as a “reporter” or “journalist” as he attempts to get through crowds. The director of the Congressional press galleries within the Senate Press office did a name check on Samuel Christopher Montoya and confirmed that no one by that name has Congressional press credentials as an individual or via any other organizations.

Montoya’s case has been continued on his own initiative since then. Given the discovery notices he has gotten — from AUSA Candice Wong — he had been treated as part of the mob most closely involved in the scene at Ashli Babbitt’s shooting. On December 10, Montoya got discovery from the Statutory Hall Connector that other defendants in that group did not get, and a different prosecutor, Alexis Loeb, took over his case. Loeb’s January 6 caseload is eclectic, but in October she started taking over the case of Proud Boys Joshua Pruitt, and Nicholas Ochs and Nicholas DeCarlo, and she has always been in charge of the prosecution of the pair that played a key role in opening the East doors from the inside, George Tenney and Darrell Youngers.

In August, Shroyer was arrested. His arrest was opportunistic, relying on the fact that he had a still-unsatisfied Deferred Prosecution Agreement arising from his attempts to disrupt Trump’s first impeachment making his loud presence inside the restricted are of the Capitol uniquely illegal. He filed a motion to dismiss his case, which was basically the cover story about de-escalation that Jones offered up immediately after the riot and Ali Alexander prepared to deliver to Congress last week. In a filing debunking that cover story, the government noted that calling for revolution — as Shroyer and Jones did from the top of the East steps — does not amount to de-escalation.

Even assuming the defendant’s argument is true and the defendant received permission to go to the Capitol steps for the limited purpose of deescalating the situation, the defendant did not even do that. Quite the opposite. Despite the defendant’s arguments today that “Shroyer did nothing but offer his assistance to calm the crowd and urge them to leave United States Capitol grounds,” Dkt. 8-1 at 14, the defendant himself said otherwise in an open-source video recorded on August 21, 2021: “From the minute we got on the Capitol, the Capitol area, you [referring to Person One] started telling people to stand down, and the second we got on there, you got up on stacks of chairs, you said, ‘We can’t do this, stand down, don’t go in.’ … And I’m silent during all of this” (emphasis added).11 Moreover, as seen in other videos and described above, the defendant forced his way to the top of Capitol Building’s east steps with Person One and others and led hundreds of other rioters in multiple “USA!” and “1776!” chants with his megaphone. Harkening to the last time Americans overthrew their government in a revolution while standing on the Capitol steps where elected representatives are certifying a Presidential Election you disagree with does not qualify as deescalation.

Shroyer let the due date to reply to this debunking, November 22, pass without filing anything. A status conference that had originally been scheduled for Tuesday, December 14 has been rescheduled for Monday December 20.

As I said in my taxonomy post, the government seems to be very close to being able to demonstrate how that the breach of the second front worked, an effort on which the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, and Alex Jones seemed to coordinate.

Doing so will be very important in demonstrating how the militia conspiracies worked. But if DOJ finds a way to charge Alex Jones for his role as the Pied Piper of insurrection, the organizer-inciter who provided the bodies needed to fill that second breach, it would bring the January 6 investigation up to an order issued directly by the former President.

The investigation of three InfoWars figures — Montoya, Shroyer, and Jones — who all have legitimate claims to be media figures happens even as DC judges are getting more insistent that DOJ adhere to Merrick Garland’s own media guidelines. In November, for example, Chief Judge Beryl Howell required prosecutors to acknowledge the media guidelines if they sought orders and warrants targeting news media.

Of course, Alexander has no such press protection, and his decision to go mouth off to Congress for seven hours last week may prove as self-destructive as the similar decision by his mentor, Roger Stone, four years ago.

The government seems to have a pretty good case about how the multi-front breach of the Capitol worked. The question is whether First Amendment protections will shield those who made that breach possible from prosecution.