How Trump Distracted from Results of His Incitement by Recruiting Journalists to Spread More of It

On Wednesday, numerous journalists reported on a filing submitted in support of Judge Arthur Engoron’s limited gag on Donald Trump. It included an affidavit from an officer from NY’s Department of Public Safety describing the threats that Judge Engoron and his chief clerk have suffered as a result of Trump’s targeting of them (this link doesn’t work for me, but should for you; here’s a DC Circuit filing including it).

Specifically, it described how, after Trump posted a picture claiming that Engoron’s chief clerk was “Schumer’s girlfriend” on October 3, Engoron and the clerk got hundreds of threatening voice mails. People started calling the clerk’s personal cell phone 20 to 30 times a day and harassing her on her private email and on social media sites.

According to the affidavit, when Trump attacked, the attacks went up. When he was gagged, the attacks went down.

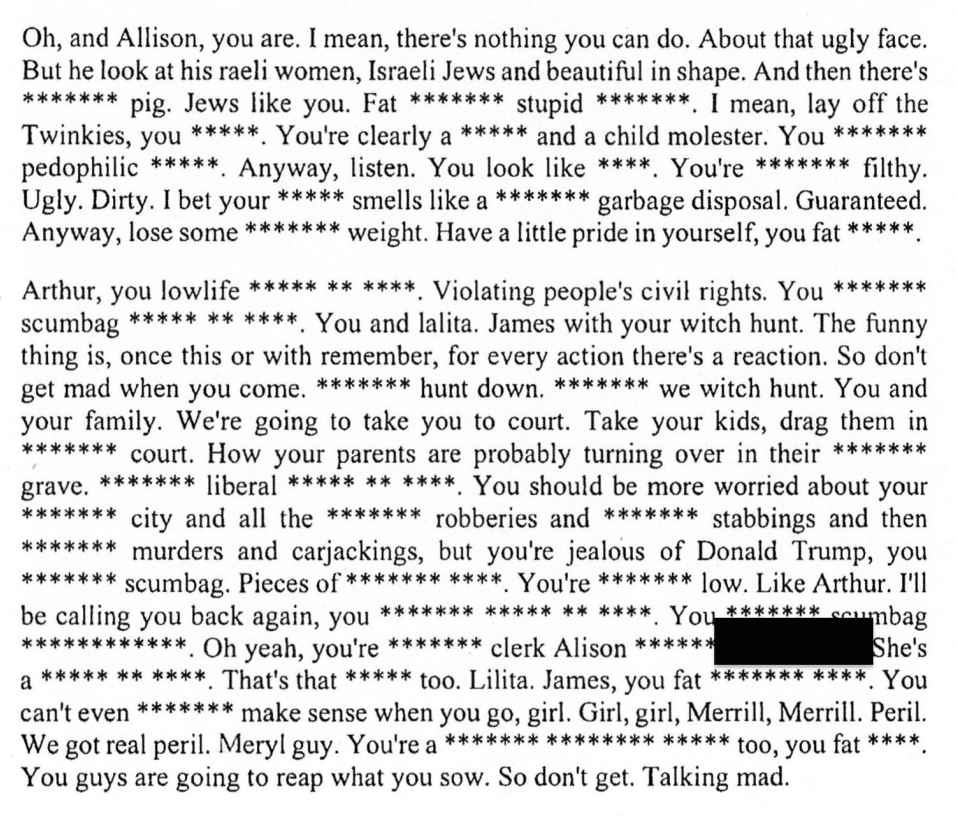

The affidavit transcribed just seven of the calls targeting Engoron or the clerk, replacing the expletives with asterisks. Those transcripts are shocking and ugly — and make it clear how Trump’s deranged followers are internalizing and then passing on his attacks.

The filing was a concrete example of how Trump’s incitement works. It shows how his own language gets parroted directly onto the voice mails and social media accounts of those he targets.

A number of people shared these threats on social media. It was a vivid demonstration of the effect of Trump’s incitement.

The next day, on Thanksgiving, Trump posted another attack on Truth Social, attacking Tish James, Engoron, the clerk, Joe Biden, and “all of the other Radical Left Lunatics, Communists, Fascists, Marxists, Democrats, & RINOS,” after which he promised to win in 2024.

It was, at its heart, a campaign ad. Trump has repeatedly said in court filings that he is running on a claim that he is being unfairly treated like other American citizens and if he is made President again, he’ll retaliate against all the people who thought to treat him just like everyone else. His promise of retribution is how he plans to win the election.

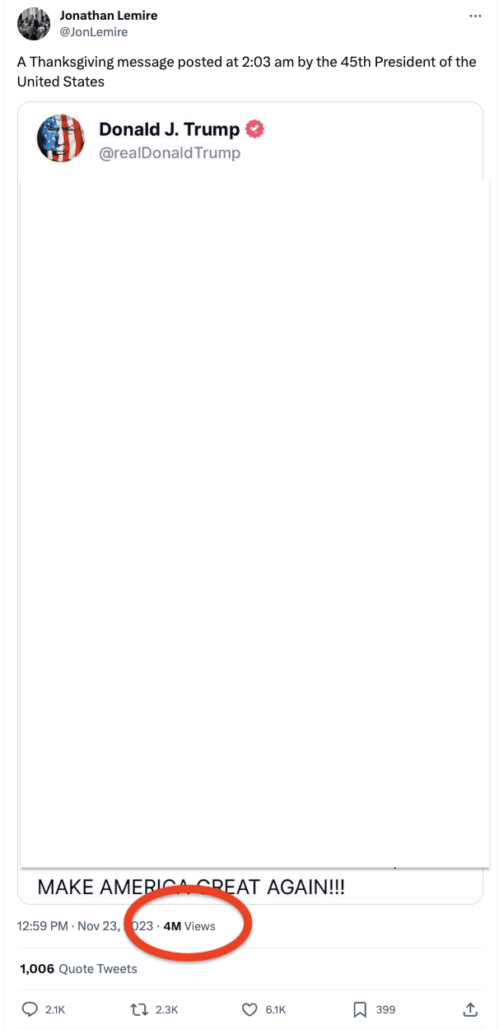

A bunch of people purporting to engage in journalism or criticism disseminated the attack on Xitter, where it went viral. As of right now, for example, Jonathan Lemire’s dissemination of Trump’s incitement and campaign ad, to a platform riddled with right wing extremists, has 4 million views.

Rather than focusing on family or the Lions losing at football, a number of people were disseminating Trump’s campaign ad, disseminating the campaign ad because he incited violence.

Importantly, these self-imagined journalists and critics disseminated Trump’s attacks in the form he packaged it up, including with the clerk’s name unredacted. They disseminated it in the way most likely to lead to more attacks on the clerk.

There’s a conceit among those who choose to disseminate Trump’s incitement and campaign ads in precisely the way he has chosen to package them up that doing so is the only way to alert Americans to the danger he poses. Brian Klass (whose book on corruption and power is superb) recently suggested that those of us who oppose platforming Trump’s incitement in the spectacular form he releases it are arguing you shouldn’t cover it.

On the political left, there has long been a steady drumbeat of admonishment on social media for those who highlight Trump’s awful rhetoric. Whenever I tweet about Trump’s dangerous language, there’s always the predictable refrain from someone who replies: “Don’t amplify him! You’re just spreading his message.”

The press, to an astonishing extent, has followed that admonishment. I looked at the New York Times for mention of Trump calling to execute shoplifters, or water the forests, or how he thinks an 82 year-old man getting his skull smashed in his own home by a lunatic with a hammer is hilarious. Nothing. I couldn’t find it.

If it was covered, it was buried deep. Scrolling through my New York Times app on Saturday, I saw dozens of political stories before getting to a piece titled “The Pumpkin Spice Latte Will Outlive Us All” and “DogTV is TV for Dogs. Except When It’s For People.” But there was nothing about Trump’s speech.

This approach has backfired. It’s bad for democracy. The “Don’t Amplify Him” argument is disastrous. We need to amplify Trump’s vile rhetoric more, because it will turn persuadable voters off to his cruel message.

Right now, Trump is still popular, still getting his message out. The people most likely to be radicalized by him, or to act on his incitement already hear him loud and clear.

Klass’ Tweet, disseminating Trump’s incitement and campaign ad, has 34K views.

That’s not what we’re arguing. It’s certainly not what I’m arguing.

You always have a choice.

You always have a choice whether to discuss Trump’s danger in the form he chooses — in the form he has carefully perfected to have maximal effect — or to disseminate and discuss it in other forms, at the very least using an “X” or something else to break up the spectacle he has crafted.

The choice particularly mattered yesterday.

Not only was Trump’s incitement a campaign ad. Not only did it name the clerk he is trying to target. But he is also setting up a Supreme Court argument that these threats are not the result of his own incitement, but instead a heckler’s veto trying to frame Trump for violence against his targets. There’s a non-zero chance Trump will cite all the critics who think they’re helping in his bid to get Sammy Alito and Clarence Thomas endorse this incitement as protected campaign speech. Trump is already arguing that courts can’t limit his incitement because so many other people, including critics, disseminate his speech.

But the choice of what form to disseminate Trump’s speech was particularly stark yesterday, as it was equally easy to show the results of Trump’s incitement, those calls to the judge and his clerk, as it was to disseminate the one best designed to incite more threats and reinforce divisions between those who criticize Trump’s speech and those who relish it.

You always have a choice how to disseminate Trump’s incitement.