NATO found it necessary yesterday to trot out a high-ranking spokesman to try to tamp down the suggestion from Dianne Feinstein and Mike Rogers over the weekend that the Taliban has increased in strength. Unfortunately for NATO, however, there are more reasons to believe that the Taliban is in a strong position than just statements emanating from Washington power players. The Taliban themselves seem also to sense their stronger position, as evidenced by their abandoning the “secret” negotiations that the US had entered into with them over the winter. The caution exhibited by Hamid Karzai as he prepares to accept the handoff of security control for more of Afghanistan also reflects a strengthening of the Taliban’s position.

It seems only fitting that since CNN was where Feinstein and Rogers made their claim that the Taliban is stronger that NATO would choose CNN for their push-back on the idea:

A top coalition official on Wednesday disputed lawmakers’ assertions that the Taliban are increasing their strength in Afghanistan.

“I’m afraid for the Taliban the evidence is rather different,” said British army Lt. Gen. Adrian Bradshaw, deputy commander for NATO’s International Security Assistance Force, in a briefing with reporters from Kabul.

The Taliban’s ability to deliver attacks in Afghanistan was reduced by almost 10% in 2011, said Bradshaw, adding that the NATO-led force is seeing a similar trend early this year.

“We get reporting, reliable reporting of Taliban commanders, feeling under pressure with lack of weapons and equipment, with lack of finance,” he said.

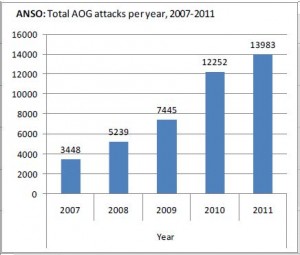

Bradshaw is of course gaming the figures. The independent group Afghanistan NGO Safety Office, or ANSO, reported that for 2011 (pdf), attacks by Armed Opposition Groups (AOG, described as the Taliban, Haqqani Network and Hezb-i-Hekmatyar) continued its upward trend in 2011, as seen in the figure above, rather than going down as Bradshaw would have us believe.

Reuters reports on the concerns surrounding the next step in handing over security control in Afghanistan:

Afghanistan faces tougher security challenges in the next phase of a transition from foreign to Afghan forces as insurgents step up their attacks, Afghan officials said on Thursday.

President Hamid Karzai is expected to announce on Sunday the transfer of 230 districts and the centers of all provincial capitals to Afghan control in the third phase of a handover before most NATO troops pull out by the end of 2014.

/snip/

There are, however, few signs of improving security in Afghanistan. Insurgents are already mounting a spring campaign of suicide attacks, while talks with the Taliban as part of efforts to reach a political settlement appear to have stalled.

Karen DeYoung has a long article in the Washington Post describing the stalled Taliban talks and the fallout from this failure.

DeYoung ties the stalled talks to the Taliban spring offensive and points out how the Obama administration had been planning to take advantage of the progress that has eluded them:

The administration had anticipated significant movement in the discussions by this month’s NATO summit in Chicago, where Afghan President Hamid Karzai and the alliance expect to set a course for the withdrawal of all U.S. and coalition combat troops from Afghanistan by the end of 2014.

In addition to political reconciliation in Afghanistan, the talks had been expected to result in the release of Bowe Bergdahl, whose parents have become so frustrated by the impasse that they have chosen the very risky strategy of speaking up about the failed negotiations.

DeYoung goes on to describe some of the jockeying for position that now assumes more power for the Taliban and a very weak position for Karzai as NATO withdraws:

Administration officials counter that Karzai — whose final term in office is scheduled to end with elections in 2014 — has not been able to build political support among Afghanistan’s fractured ethnic and regional groups for a brokered solution to the war.

/snip/

Tajiks and Uzbeks in northern Afghanistan, who ousted the Taliban government in 2001 with Americans’ help, fear that Karzai will allot positions of power to his fellow Pashtuns and have begun rebuilding militias that were disbanded after the Taliban defeat. They are openly seeking assistance from other Asian powers who share their concerns.

/snip/

The northern leaders and many civil society activists consider an ongoing U.S. military presence as protection against Taliban expansion. But many other non-insurgent Afghans are suspicious of long-term U.S. aims and believe there will be no peace without a complete American withdrawal.

It’s not just “other Asian powers who share their concerns” who are banding together to strengthen warlords from the north. As I pointed out late in April, Congressman Dana Rohrabacher is attempting to bring back war criminal Rashid Dostum to lead the Northern Alliance once again as a counter to the Taliban. In retrospect, Rohrabacher’s endorsement of Dostum stands out as one of the strongest pieces of evidence we have to date that the Taliban has significantly increased its strength and seeks to grab even more power through violence rather than at the negotiating table.