Eleven Days after Releasing Their Report, DOJ IG Clarified What Crimes FBI Investigated

The DOJ IG’s office has made two sets of corrections to their Report on Carter Page, the first on December 11 (two days after its release) and a second on December 20 (eleven days after its release). Three of those corrections fix overstatements of their case against the FBI (but which don’t catch all their overstatements and errors in making that case). One correction explains that more information has been declassified (without explaining an inconsistent approach to Sergei Millian as compared with other people named in the Mueller Report). And one correction — one of the changes made Friday — fixes a legal reference.

Here’s that correction:

On page 57, we added the specific provision of the United States Code where the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) is codified, and revised a footnote in order to reference prior OIG work examining the Department’s enforcement and administration of FARA.

The correction changed this passage…

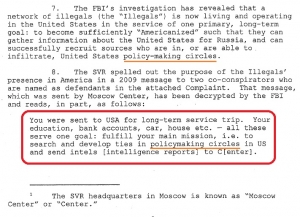

Crossfire Hurricane was opened by [FBI’s Cyber and Counterintelligence Division] and was assigned a case number used by the FBI for possible violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), Title 18 U.S.C. § 951, which makes it a crime to act as an agent of a foreign government without making periodic public disclosures of the relationship. 170

170 The FARA statute defines an “agent of a foreign government” as an individual who agrees to operate in the United States subject to the direction or control of a foreign government or official. 18 U.S.C. § 951(d).

To read like this:

Crossfire Hurricane was opened by CD and was assigned a case number used by the FBI for possible violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), 22 U.S.C. § 611, et seq., and 18 U.S.C. § 951 (Agents of Foreign Governments). 170

170 We have previously found differing understandings between FBI agents and federal prosecutors and NSD officials about the intent of FARA as well as what constitutes a “FARA case.” See DOJ OIG, Audit of the National Security Division~ Enforcement and Administration of the Foreign Agents Registration Act, Audit Division 16-24 (September 2016), https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2016/al624.pdf (accessed December 19, 2019)

The error appears harmless on its face, just a minor citation error that conflated FARA with 951 in the original report. But both in this instantiation and in the IG Report as a whole, the error may totally undermine its analysis and, indeed, the analytical framework of this entire IG investigation. That’s because if the people conducting this analysis did not understand the difference between the two statutes — and the error goes well beyond the citation enhancement described in the correction, because it exhibits utter lack of knowledge that there are two foreign agent statutes — then the Report’s analysis on the First Amendment may be problematic (and almost certainly is with respect to Page).

As I’ve written at length and as the cited IG Report from 2016 explains, the boundary between 22 USC 611 (FARA) and 18 USC 951 (Foreign Agent), both laws about what makes someone a “foreign agent,” remains ambiguous. Maria Butina, Anna Chapman, and the Russians who tried to recruit Carter Page were prosecuted under 18 USC 951 (though often that gets charged as a conspiracy because proving it requires less classified evidence), Paul Manafort, Rick Gates, and Sam Patten pled guilty to FARA violations. Mike Flynn’s former partner, Bijan Kian, was charged with conspiring to file a false FARA filing and acting as a Foreign Agent, invoking both statutes in one conspiracy charge; partly because of the way he was charged and partly because Flynn reneged on his statements regarding their activities, Judge Anthony Trenga acquitted him after he was found guilty, which may suggest the boundary between the two will present legal difficulties for prosecuting such cases.

18 USC 951 is sometimes called “espionage light,” though that phrase ignores that DOJ will often charge a known foreign spy under 951 — like the SVR (foreign intelligence) agents who tried to recruit Page — because proving it requires far less classified information. It requires the person be working on behalf of a foreign government, not just a foreign principal, and can but does not necessarily include information collection. FARA, however, only requires a person to be working on behalf of a foreign principal (which might be a political party or a company), and generally pertains to political influence peddling (it includes political activities, lobbying, and PR in its definitions, along with some financial stuff). 18 USC 951 will more often be clandestine, though as Butina’s case shows, it does not have to be, whereas FARA may cover activities that are overt if the person engaging in them does not register properly. A recent Lawfare post describes how DOJ’s superseding indictment of the Internet Research Agency relies on an interesting and potentially troubling new application of FARA.

In Mueller’s description of how the two laws might be applied criminally, he suggests 951 does not require willfulness, but a criminal violation of FARA would.

The Office next assessed the potential liability of Campaign-affiliated individuals under federal statutes regulating actions on behalf of, or work done for, a foreign government.

a. Governing Law

Under 18 U.S.C. § 951, it is generally illegal to act in the United States as an agent of a foreign government without providing notice to the Attorney General. Although the defendant must act on behalf of a foreign government (as opposed to other kinds of foreign entities), the acts need not involve espionage; rather, acts of any type suffice for liability. See United States v. Duran, 596 F.3d 1283, 1293-94 (11th Cir. 2010); United States v. Latchin, 554 F.3d 709, 715 (7th Cir. 2009); United States v. Dumeisi, 424 F.3d 566, 581 (7th Cir. 2005). An “agent of a foreign government” is an ” individual” who “agrees to operate” in the United States “subject to the direction or control of a foreign government or official.” 18 U.S.C. § 951 ( d).

The crime defined by Section 951 is complete upon knowingly acting in the United States as an unregistered foreign-government agent. 18 U.S.C. § 95l(a). The statute does not require willfulness, and knowledge of the notification requirement is not an element of the offense. United States v. Campa, 529 F.3d 980, 998-99 (11th Cir. 2008); Duran, 596 F.3d at 1291-94; Dumeisi, 424 F.3d at 581.

The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) generally makes it illegal to act as an agent of a foreign principal by engaging in certain (largely political) activities in the United States without registering with the Attorney General. 22 U.S.C. §§ 611-621. The triggering agency relationship must be with a foreign principal or “a person any of whose activities are directly or indirectly supervised, directed, controlled, financed, or subsidized in whole or in major part by a foreign principal.” 22 U.S.C. § 61 l(c)(l). That includes a foreign government or political party and various foreign individuals and entities. 22 U.S.C. § 611(6). A covered relationship exists if a person “acts as an agent, representative, employee, or servant” or “in any other capacity at the order, request, or under the [foreign principal’s] direction or control.” 22 U.S.C. § 61 l(c)(l). It is sufficient if the person “agrees, consents, assumes or purports to act as, or who is or holds himself out to be, whether or not pursuant to contractual relationship, an agent of a foreign principal.” 22 U.S.C. § 61 l(c)(2).

The triggering activity is that the agent “directly or through any other person” in the United States (1) engages in “political activities for or in the interests of [the] foreign principal,” which includes attempts to influence federal officials or the public; (2) acts as “public relations counsel, publicity agent, information-service employee or political consultant for or in the interests of such foreign principal”; (3) ” solicits, collects, disburses, or dispenses contributions, loans, money, or other things of value for or in the interest of such foreign principal”; or ( 4) “represents the interests of such foreign principal” before any federal agency or official. 22 U .S.C. § 611 ( c )(1 ).

It is a crime to engage in a “[w]illful violation of any provision of the Act or any regulation thereunder.” 22 U.S.C. § 618(a)(l). It is also a crime willfully to make false statements or omissions of material facts in FARA registration statements or supplements. 22 U.S.C. § 618(a)(2). Most violations have a maximum penalty of five years of imprisonment and a $10,000 fine. 22 U.S.C. § 618. [my emphasis]

So back to the DOJ IG Report. As the revised footnote notes, at least until 2016, the FBI used the same case number for FARA and 951 cases. That probably makes sense from an investigative standpoint, as it’s often not clear whether someone is working for a foreign company or whether that company is a cut-out hiding a foreign government paymaster (as the government alleged in Flynn’s case). But it makes tracking how these cases get investigated more difficult, and obscures those cases where there’s a clear 951 predicate from the start.

The original text of this passage of the IG Report suggests that at least the person who wrote it — and possibly the entire DOJ IG team investigating this case — were not aware of what I’ve just laid out, that there’s significant overlap between 951 and FARA, but that clear 951 cases and clear FARA cases will both use this case designation. That’s important because one of these statutes involves politics (and so presents serious First Amendment considerations), whereas the other one does not have to (and did not, in Carter Page’s case).

It’s unclear whether this error was repeated in several other places in the Report. The passage describing how the individualized investigations were opened says these were all FARA cases:

After conducting preliminary open source and FBI database inquiries, intelligence analysts on the Crossfire Hurricane team identified three individuals–Carter Page, Paul Manafort, and Michael Flynn–associated with the Trump campaign with either ties to Russia or a history of travel to Russia. On August 10, 2016, the team opened separate counterintelligence FARA cases on Carter Page, Manafort, and Papadopoulos, under code names assigned by the FBI. On August 16, 2016, a counterintelligence FARA case was opened on Flynn under a code name assigned by the FBI. The opening ECs for all four investigations were drafted by either of the two Special Agents assigned to serve as the Case Agents for the investigation (Case Agent 1 or Case Agent 2) and were approved by Strzok, as required by the DIOG.

But if the person writing this did not know that a “foreign agent” case might be FARA, 951, or both, then it would mean this passage may misstate what the investigations were.

And the analysis over whether the investigation was appropriately predicated uses just FARA.

The FBI’s opening EC referenced the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) and stated, “[b]ased on the information provided by [the FBI Legal Attache], this investigation is being opened to determine whether individual(s) associated with the Trump campaign are witting of and/or coordinating activities with the Government of Russia.”

In other words, it seems that this entire report is based on the assumption that the FBI was conducting an investigation into whether these four men were engaged in influence peddling that should have been registered and not also considering whether they were acting as clandestine agents for Russia.

That certainly appears to be the case for some of these men. For example, the first known warrant investigating Paul Manafort — which was focused on his Ukrainian work — listed only FARA, not 951. The derogatory language on George Papadopoulos speaks in terms of explicit, shameless influence peddling (which I’ll review in a follow-up post).

That said, the predication of the Flynn investigation would have included his past ties to the GRU, the agency that had hacked the DNC, and non-political relationships with Russian companies RT, Kaspersky, and Volga-Dnepr Airlines. He notified the Defense Intelligence Agency of all those things, though the government claims some of his briefings on this stuff includes inculpatory information. And he excused his payments from other Russian sources because his speakers bureau, and not Russia itself, made the payments, which might be considered a cut-out.

When Mueller got around to describing his prosecutorial decisions about these four men, he described both statutes (and explained that the office found that Manafort and Gates had violated FARA with Ukraine, Flynn had violated what it calls FARA with Turkey but elsewhere they’ve said included 951, and there was evidence Papadopoulos was an Agent of Israel under either 951 or FARA but not sufficient to charge.

Finally, the Office investigated whether one of the above campaign advisors-George Papadopoulos-acted as an agent of, or at the direction and control of, the government of Israel. While the investigation revealed significant ties between Papadopoulos and Israel (and search warrants were obtained in part on that basis), the Office ultimately determined that the evidence was not sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction under FARA or Section 951

So it’s unclear whether the investigations into Papadopoulos, Flynn, and Manafort really were just FARA cases when they began, or were 951.

But the language Mueller used to describe his declination for Page (which includes a redacted sentence about his activities) makes it sound like his FISA applications alleged him to be — as would have to be the case for a FISA order — an Agent of Russia, implicating 951.

On four occasions, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) issued warrants based on a finding of probable cause to believe that Page was an agent of a foreign power. 50 U.S.C. §§ 1801 (b ), 1805(a)(2)(A). The FISC’s probable-cause finding was based on a different (and lower) standard than the one governing the Office’s decision whether to bring charges against Page, which is whether admissible evidence would likely be sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Page acted as an agent of the Russian Federation during the period at issue. Cf United States v. Cardoza, 713 F.3d 656, 660 (D.C. Cir. 2013) ( explaining that probable cause requires only “a fair probability,” and not “certainty, or proof beyond a reasonable doubt, or proof by a preponderance of the evidence”).

Indeed, the IG Report provides abundant reason to believe this is the case. That’s because the FBI Field Office opened an investigation into Page in April 2016 based on a March 2016 interview pertaining exclusively to what are called “continued contacts” with SVR intelligence officers who tried to recruit him starting at least in 2009, interactions that they had been tracking for seven years.

An FBI counterintelligence agent in NYFO (NYFO CI Agent) with extensive experience in Russian matters told the OIG that Carter Page had been on NYFO’s radar since 2009, when he had contact with a known Russian intelligence officer (Intelligence Officer 1). According to the EC documenting NYFO’s June 2009 interview with Page, Page told NYFO agents that he knew and kept in regular contact with Intelligence Officer 1 and provided him with a copy of a non-public annual report from an American company. The EC stated that Page “immediately advised [the agents] that due to his work and overseas experiences, he has been questioned by and provides information to representatives of [another U.S. government agency] on an ongoing basis.” The EC also noted that agents did not ask Page any questions about his dealings with the other U.S. government agency during the interviews. 180

NYFO CI agents believed that Carter Page was “passed” from Intelligence Officer 1 to a successor Russian intelligence officer (Intelligence Officer 2) in 2013 and that Page would continue to be introduced to other Russian intelligence officers in the future. 181 In June 2013, NYFO CI agents interviewed Carter Page about these contacts. Page acknowledged meeting Intelligence Officer 2 following an introduction earlier in 2013. When agents intimated to Carter Page during the interview that Intelligence Officer 2 may be a Russian intelligence officer, specifically, an “SVR” officer, Page told them he believed in “openness” and because he did not have access to classified information, his acquaintance with Intelligence Officer 2 was a “positive” for him. In August 2013, NYFO CI agents again interviewed Page regarding his contacts with Intelligence Officer 2. Page acknowledged meeting with Intelligence Officer 2 since his June 2013 FBI interview.

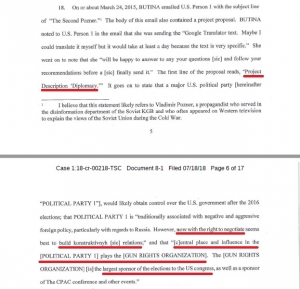

In January 2015, three Russian intelligence officers, including Intelligence Officer 2, were charged in a sealed complaint, and subsequently indicted, in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) for conspiring to act in the United States as unregistered agents of the Russian Federation. 182 The indictment referenced Intelligence Officer 2’s attempts to recruit “Male-1” as an asset for gathering intelligence on behalf of Russia.

On March 2, 2016, the NYFO CI Agent and SDNY Assistant United States Attorneys interviewed Carter Page in preparation for the trial of one of the indicted Russian intelligence officers. During the interview, Page stated that he knew he was the person referred to as Male-1 in the indictment and further said that he had identified himself as Male-1 to a Russian Minister and various Russian officials at a United Nations event in “the spirit of openness.” The NYFO CI Agent told us she returned to her office after the interview and discussed with her supervisor opening a counterintelligence case on Page based on his statement to Russian officials that he believed he was Male-1 in the indictment and his continued contact with Russian intelligence officers.

The FBI’s NYFO CI squad supervisor (NYFO CI Supervisor) told us she believed she should have opened a counterintelligence case on Carter Page prior to March 2, 2016 based on his continued contacts with Russian intelligence officers; however, she said the squad was preparing for a big trial, and they did not focus on Page until he was interviewed again on March 2. She told us that after the March 2 interview, she called CD’s Counterespionage Section at FBI Headquarters to determine whether Page had any security clearances and to ask for guidance as to what type of investigation to open on Page. 183 On April 1, 2016, the NYFO CI Supervisor received an email from the Counterespionage Section advising her to open a [~9-character redaction] investigation on Page. The NYFO CI Supervisor said that [3 lines redacted] In addition, according to FBI records, the relevant CD section at FBI Headquarters, in consultation with OGC, determined at that time that the Page investigation opened by NYFO was not a SIM, but also noted, “should his status change, the appropriate case modification would be made.” The NYFO CI Supervisor told us that based on what was documented in the file and what was known at that time, the NYFO Carter Page investigation was not a SIM.

Although Carter Page was announced as a foreign policy advisor for the Trump campaign prior to NYFO receiving this guidance from FBI Headquarters, the NYFO CI Supervisor and CI Agent both told the OIG that this announcement did not influence their decision to open a case on Page and that their concerns about Page, particularly his disclosure to the Russians about his role in the indictment, predated the announcement. However, the NYFO CI Supervisor said that the announcement required noting his new position in the case file should his new position require he obtain a security clearance.

On April 6, 2016, NYFO opened a counterintelligence [8-9 character redaction] investigation on Carter Page under a code name the FBI assigned to him (NYFO investigation) based on his contacts with Russian intelligence officers and his statement to Russian officials that he was “Male-1” in the SONY indictment.

181 CI agents refer to this as “slot succession,” whereby a departing intelligence officer “passes” his or her contacts to an incoming intelligence officer.

182 Intelligence Officer 3 pied guilty in March 2016. The remaining two indicted Russian intelligence officers were no longer in the United States.

183 CI agents in NYFO told us that the databases containing security clearance information were located at FBI Headquarters. When a subject possesses a security clearance, the FBI opens an espionage investigation; if the subject does not possess a security clearance, the FBI typically opens a counterintelligence investigation. [my emphasis]

I’ve discussed Page’s designation as a “contact approval” until 2013 by CIA here, though to reiterate, his last contact with the CIA was in 2011, and while they knew about his contacts with Alexander Bulatov, a Russian intelligence officer working under cover as a consular official in NY, they apparently did not know or ask him about his contacts with Victor Podobnyy. This previous relationship with the CIA absolutely should have been disclosed, but does not cover activity in 2015, when he would have discussed his inclusion in the Podobnyy/Evgeny Buryakov indictment with a person described as a Russian minister.

The NYFO believed they should have opened an investigation into Page even before the interview, on March 2, 2016, when he admitted telling Russians he was Male-1 in the indictment and (per the Mueller Report), said he “didn’t do anything,” perhaps disavowing any help to the FBI investigation. The IG Report notes that Page provided Intelligence Officer 1 (who must be Bulatov) a copy of a non-public annual report from an American company.” The Podobnyy indictment notes that Page provided Podobnyy — someone he knew to be a foreign intelligence officer — documents about the energy business. The NYFO CI Agent’s description of Page’s, “continued contact with Russian intelligence officers” seems to suggest the person described as a Russian Minister is known or believed to be an intelligence officer (otherwise she would not have described this as ongoing contact).

Notably, NYFO’s focus was not on whether Page was engaged in political activities, whether he was a Sensitive Investigative Matter (SIM) or not. Indeed, at the time they opened the investigation in April 2016, they didn’t know he had a tie to the Trump campaign.

Rather, their focus was on whether Page, whose deployments in the Navy included at least one intelligence operation, had a security clearance, because that dictated whether the investigation into him would be an Espionage one or a Counterintelligence one. The actual type of investigation remains redacted (the word cannot be either “counterintelligence,” because of length, or “espionage” because the article preceding it forecloses the word starting with a vowel), but it is described as a counterintelligence investigation. Given the nature of the non-public information Page shared, that redacted word may pertain to economic information, perhaps to either 18 USC 1831 or 1832. Even going forward, NYFO was primarily interested in whether he would obtain a clearance that would increase the risk that the information he was happily sharing with known Russian intelligence officers would damage the US.

The counterintelligence case into Page was opened — and the FISA order targeting him was significantly predicated on — his voluntary sharing of non-public economic information with known Russian intelligence officers over a period of years. That’s almost certainly not a FARA investigation because at that point NYFO had no knowledge that Page was even engaging in politics.

And that’s important because of the IG Report’s analysis of whether and how obtaining a FISA order on Page implicated his First Amendment activities.

In its analysis of how FISA treats First Amendment activities, the Report includes the following discussion, once again citing FARA, relying on House and Senate reports on the original passage of FISA.

FISA provides that a U.S. person may not be found to be a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power solely upon the basis of activities protected by the First Amendment. 129 Congress added this language to reinforce that lawful political activities may not serve as the only basis for a probable cause finding, recognizing that “there may often be a narrow line between covert action and lawful activities undertaken by Americans in the exercise of the [F]irst [A]mendment rights,” particularly between legitimate political activity and “other clandestine intelligence activities. “130 The Report by SSCI accompanying the passage of FISA states that there must be “willful” deception about the origin or intent of political activity to support a finding that it constitutes “other clandestine intelligence activities”:

If…foreign intelligence services hide behind the cover of some person or organization in order to influence American political events and deceive Americans into believing that the opinions or influence are of domestic origin and initiative and such deception is willfully maintained in violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act, then electronic surveillance might be justified under [“other clandestine intelligence activities”] if all the other criteria of [FISA] were met. 131

129 See 50 U.S.C. §§ 1805(a)(2)(A), 1824(a)(2)(A).

130 H. Rep. 95-1283 at 41, 79-80; FISA guidance at 7-8; see also Rosen, 447 F. Supp. 2d at 547-48 (probable cause finding may be based partly on First Amendment protected activity).

131 See S. Rep. 95-701 at 24-25. The Foreign Agents Registration Act, 22 U.S.C. § 611 et seq., is a disclosure statute that requires persons acting as agents of foreign principals such as a foreign government or foreign political party in a political or quasi-political capacity to make periodic public disclosure of their relationship with the foreign principal, as well as activities, receipts and disbursements in support of those activities.

The first citation to the House report says only that an American must be working with an intelligence service and must involve a violation of Federal criminal law, which may include registration statutes. The second citation says only that political activities should never be the sole basis of a finding of probable cause that a US person was an agent of a foreign power. Neither would apply to Carter Page, since the evidence against him also included sharing non-public information that had nothing to do with politics, and he shared that information with known intelligence officers.

The citation to the Senate report is a miscitation. The quoted language appears on page 29. The cited passage spanning pages 24 and 25, however, emphasizes that someone can only be targeted for activities that involve First Amendment activities if they involve an intelligence agency.

It is the intent of this requirement that even if there is some substantial contact between domestic groups or individual citizens and a foreign power, as defined in this bill, no electronic surveillance wider this subparagraph may be authorized unless the American is acting under the direction of an intelligence service of a foreign power.

With Page, the FBI had his admitted and sustained willingness to share non-public information with known intelligence officers, the Steele allegations suggesting he might be involved in a conspiracy tied to the hack and leak of Hillary’s emails, and his stated plans to set up a think tank that would serve as the kind of cover organization that would hide Russia’s role in pushing Page’s pro-Russian views.

The question of whether Page met probable cause for being a foreign agent doesn’t, in my mind, pivot on any analysis of First Amendment activities, because he had a clear, knowing tie with Russian intelligence officers with whom he was sharing non-public information. The question pivots on whether he could be said to doing so clandestinely, since he happily admitted the fact, if asked, to both the CIA and FBI. Both the Steele allegations (until such point, after his first application, that they had been significantly undermined) and Page’s enthusiasm to set up a Russian-funded think tank probably get beyond that bar.

And remember, for better and worse, this is probable cause, not proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

The DOJ IG Report analysis all seems premised on assessing FARA violations, not violations of 18 USC 951. That may be the appropriate lens through which to assess the actions of Papadopoulos, Flynn, and Manafort.

But the evidence presented in the report seems to suggest that’s a mistaken lens through which to assess the FISA application targeting Carter Page, the only Trump flunky who was so targeted. And given the evidence that at least some of the people who wrote the report did not understand how the two statutes overlap when they conducted the analysis, it raises real questions about whether all that analysis rests on mistaken understandings of the law.

Update: I’ve corrected the introduction of this to note that DOJ or FBI declassifies information, not DOJ IG.

OTHER POSTS ON THE DOJ IG REPORT

Overview and ancillary posts

DOJ IG Report on Carter Page and Related Issues: Mega Summary Post

The DOJ IG Report on Carter Page: Policy Considerations

Timeline of Key Events in DOJ IG Carter Page Report

Crossfire Hurricane Glossary (by bmaz)

Facts appearing in the Carter Page FISA applications

Nunes Memo v Schiff Memo: Neither Were Entirely Right

Rosemary Collyer Responds to the DOJ IG Report in Fairly Blasé Fashion

Report shortcomings

The Inspector General Report on Carter Page Fails to Meet the Standard It Applies to the FBI

“Fact Witness:” How Rod Rosenstein Got DOJ IG To Land a Plane on Bruce Ohr

Eleven Days after Releasing Their Report, DOJ IG Clarified What Crimes FBI Investigated

Factual revelations in the report

Deza: Oleg Deripaska’s Double Game

The Damning Revelations about George Papadopoulos in a DOJ IG Report Claiming Exculpatory Evidence

The Carter Page IG Report Debunks a Key [Impeachment-Related] Conspiracy about Paul Manafort

Sam Clovis Responded to a Question about Russia Interfering in the Election by Raising Voter ID