I’m working on one more post integrating materials from the Douglass Mackey trial.

But first I want to comment about some investigative and prosecutorial details about the case.

I’ve made a timeline showing what got introduced in the troll chatrooms as evidence, other known activities of Mackey and the cooperating witness Microchip, and investigative details here. The timeline includes the following DM threads that were treated as part of the conspiracy for which Mackey was convicted:

In addition, this exhibit, which was introduced under a different evidentiary rule (largely, but not entirely, Mackey’s comments, rather than those of the conspiracy), consists in part of conversations elsewhere sourced to FedFreeHateChat from earlier in 2015-2016, along with a number of two-person DMs involving Mackey or unindicted co-conspirators 1080p or Microchip.

As you read the threads, remember a few things about them. First, they’ve been extensively sanitized of the racist and misogynist language used in the threads. Anything that wasn’t directly relevant to proving either the means and goals of Mackey’s trolling, a conspiracy between the thread participants, or their intent in sending out false tweets to depress the turnout of Black and Latino Hillary supporters was excluded as prejudicial.

You can read some of what was excluded — and the very important debate about where Mackey’s free speech ended and where an attempt to impair the votes of Black and Latino Hillary supporters began — in these court filings:

- January 30, 2023: Mackey’s effort to exclude pre-September 2016 language and commentary from when he was banned by Twitter and inflammatory speech

- January 30, 2023: The government’s effort to get the contents of the four chatrooms, above, admitted

- February 24, 2023: Mackey’s response to the government’s motion

- February 24, 2023: The government’s response to Mackey

- February 28, 2023: The government’s reply to Mackey

- February 28, 2023: Mackey’s reply

- March 7, 2023: Mackey letter after meet-and-confer that details objections, revealing content of some excluded files

- March 7, 2023: Government memo after meet-and-confer

- March 10, 2023: Judge Nicholas Garaufis order laying out admissible exhibits

- March 11, 2023: Mackey letter seeking to exclude bigoted speech and FBI agent testimony

- March 13, 2023: Mackey letter seeking to exclude comment about women voting

- March 13, 2023: Government letter responding regarding bigoted speech

- March 19, 2023: Mackey letter objecting to specific inflammatory language and memes showing Trump in violent conquest

The outlines of this dispute will be critical to the inevitable appeal of Mackey’s guilty verdict.

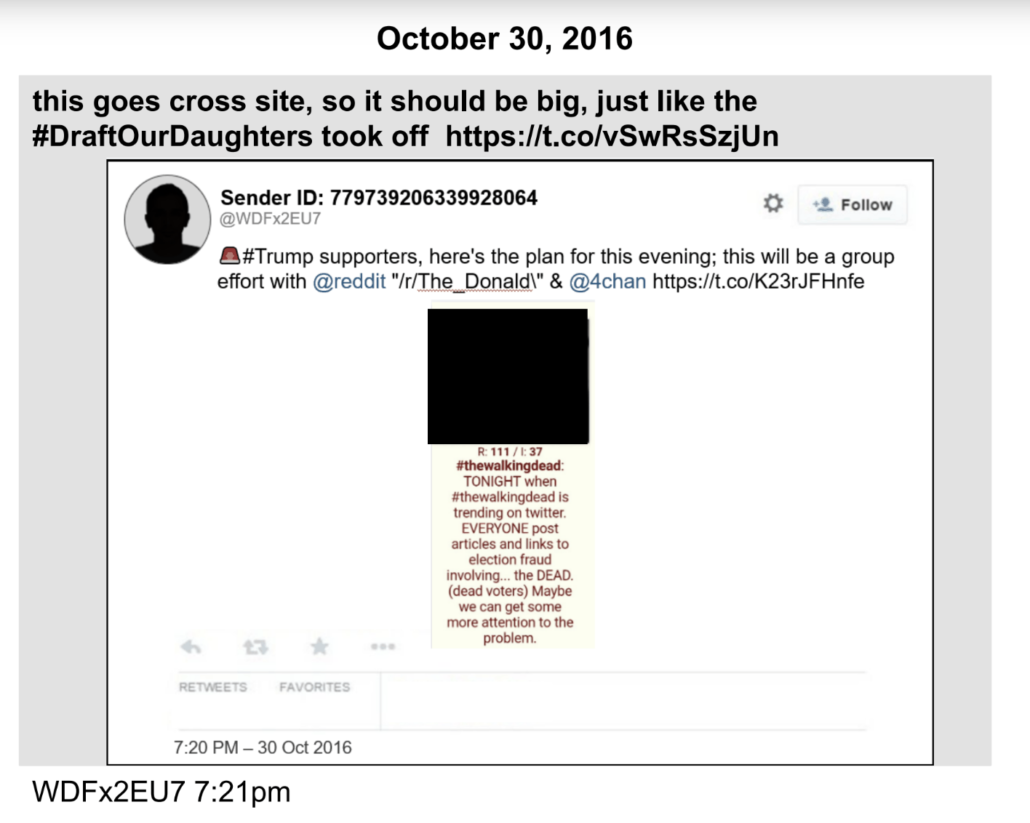

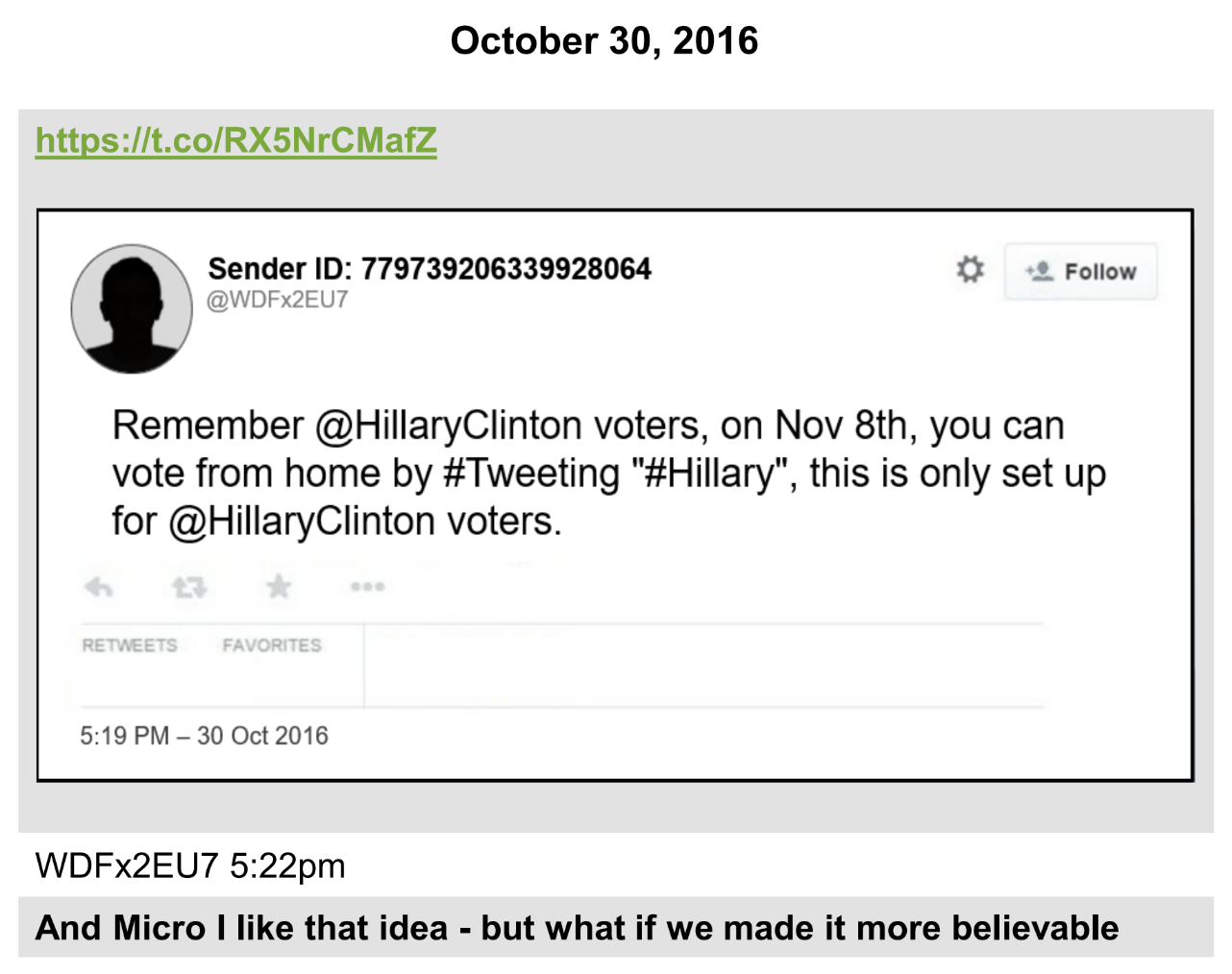

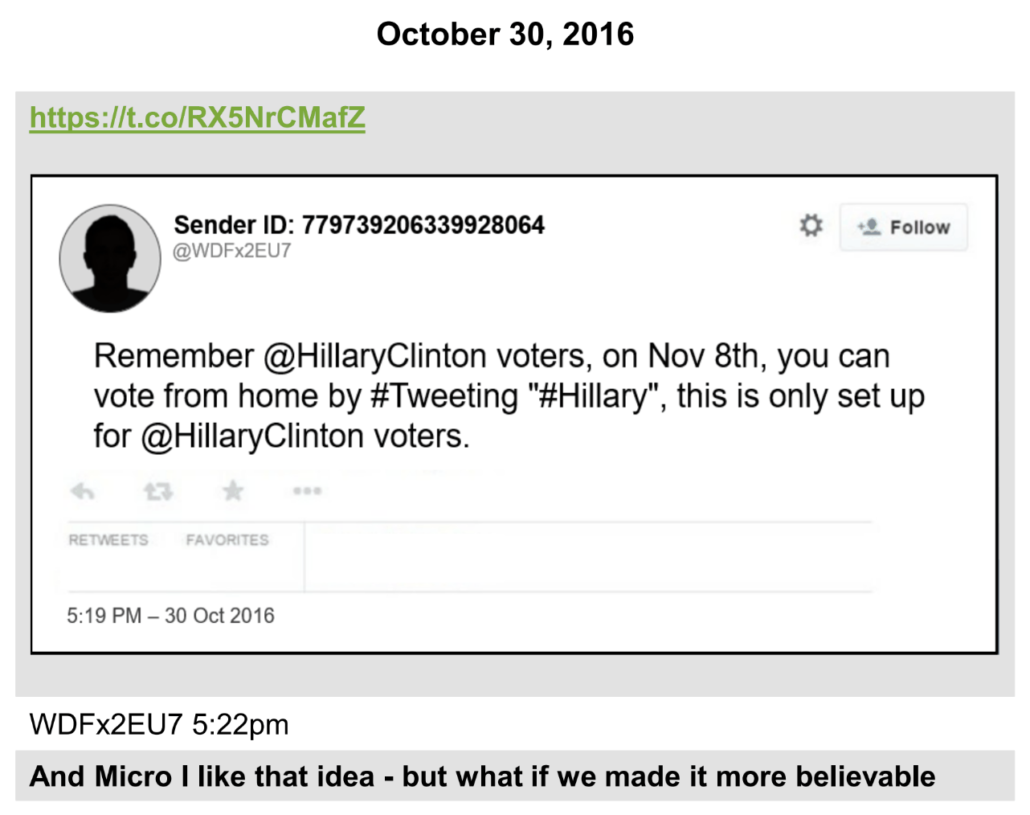

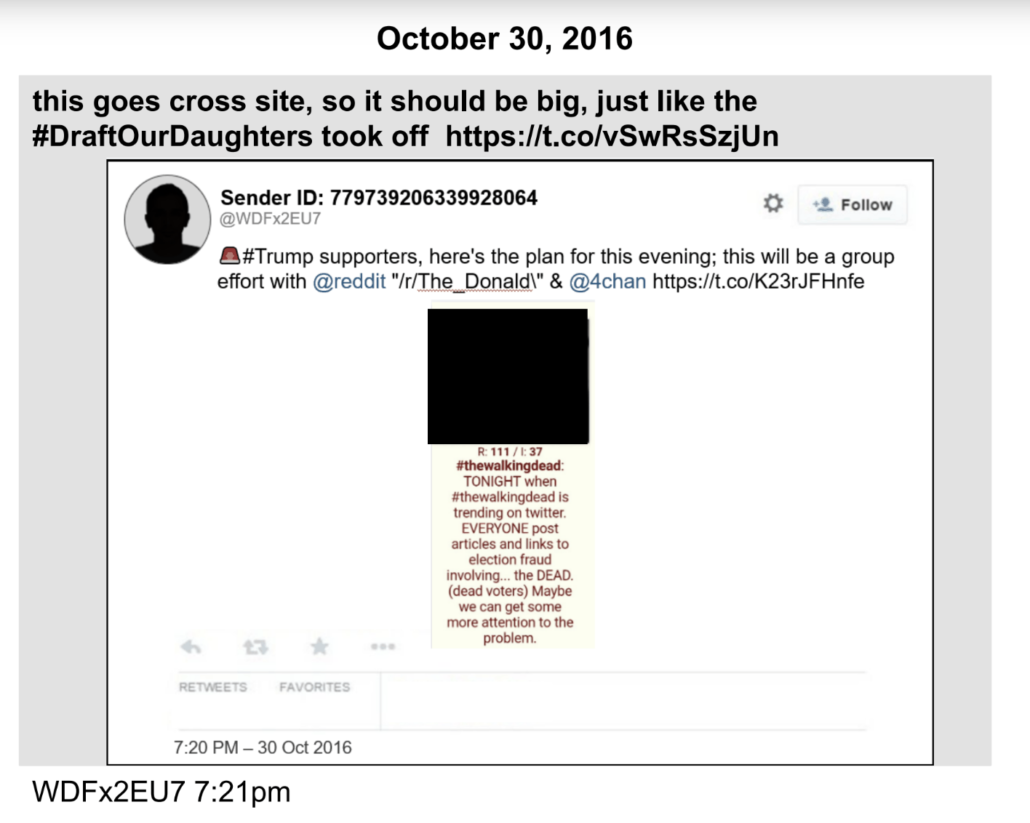

These Twitter DM groups weren’t the only places these trolls organized, as portrayed by trial evidence. After one of Mackey’s bannings, he authenticated his new Twitter ID on Facebook and continued to work with others on Discord. The government did not introduce any of the related threads from TheDonald or 4chan with which — as a tweet from Microchip made clear — their efforts on Twitter were sometimes coordinated.

The exclusion of related 4chan activity is significant. At trial, Mackey took the stand and claimed he had gotten the text-to-vote meme for which he was charged from widely available 4chan threads, not from these DM groups, one of which he did not rejoin after being banned by Twitter on October 5. Mackey similarly claimed not to know the key players in workshopping this meme in the War Room twitter group beyond their user name.

The claim was pretty unconvincing; it may have been an attempt to deny forming a conspiracy with the others, or an effort to protect his online friends.

I’m interested in the picture of the conspiracy provided by these threads for several related reasons.

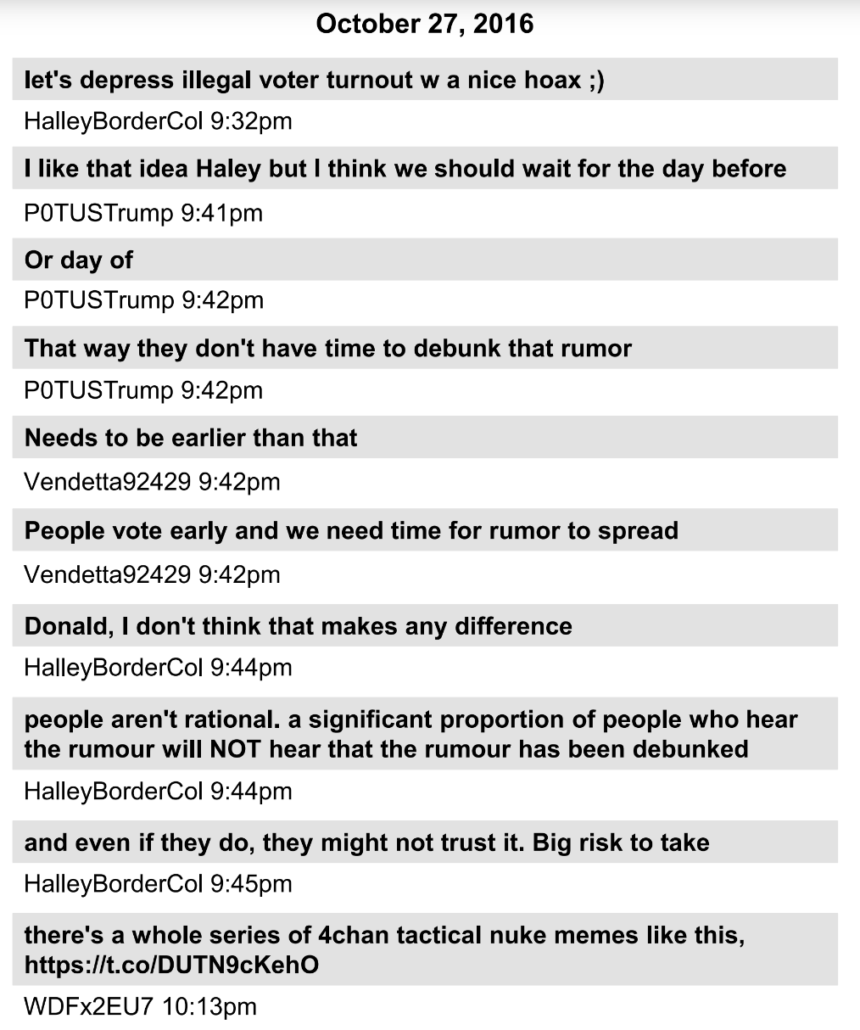

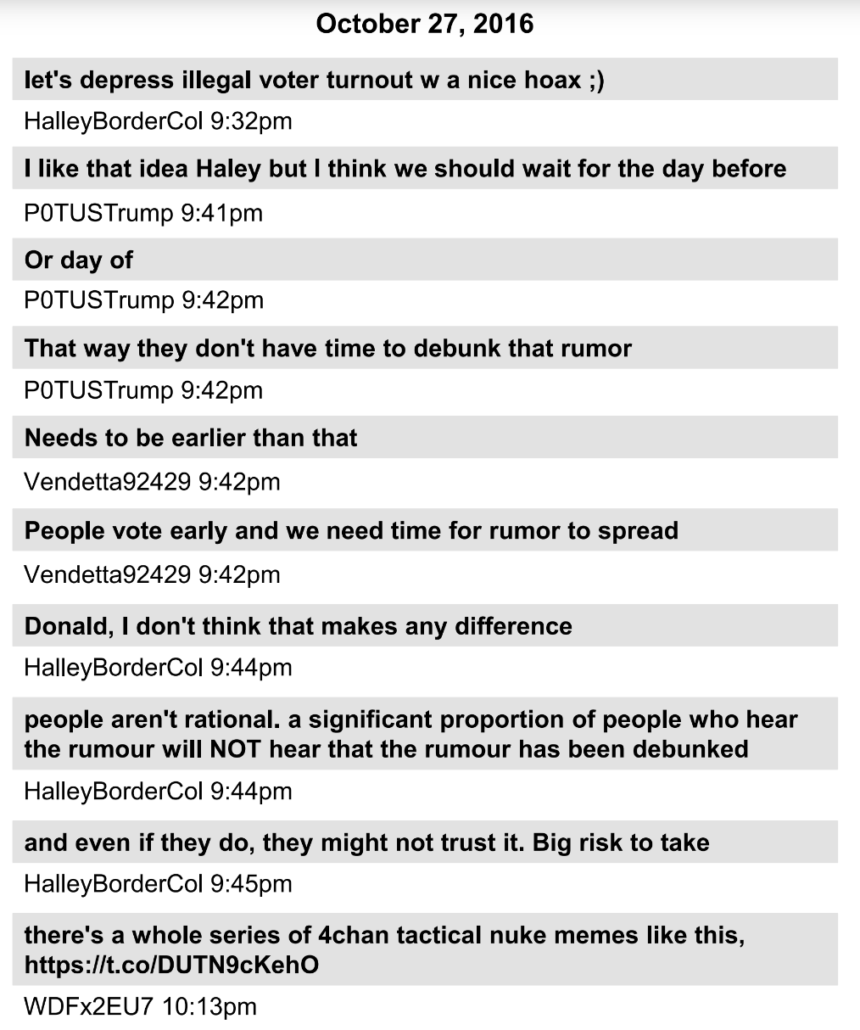

For starters, I’m interested in the troll — prosecutors referred to the account using a female pronoun — who first created a text-to-vote meme like the one that Mackey was convicted of. On October 27, 2016 on the War Room thread (which Mackey had rejoined after being banned), HalleyBorderCol (HBC) suggested, “let’s depress illegal voter turnout with a nice hoax ;).” Someone using the moniker P0TUSTrump argued they should hold off so the hoax would not get debunked before actually suppressing the vote. HBC responded by addressing him as “Donald” and explaining — using a British spelling for rumor — how rumors work, especially on social media:

people aren’t rational. a significant proportion of people who hear the rumour will NOT hear that the rumour has been debunked.

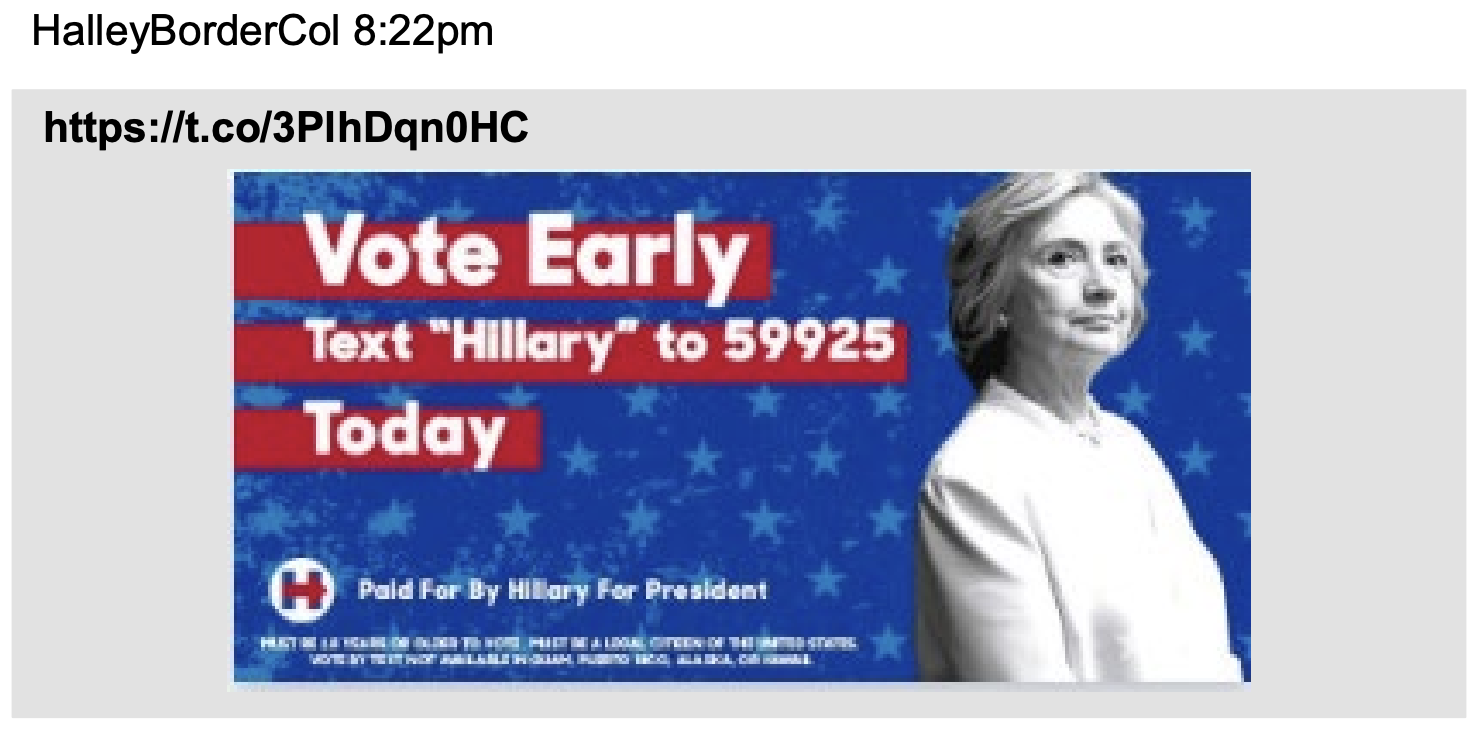

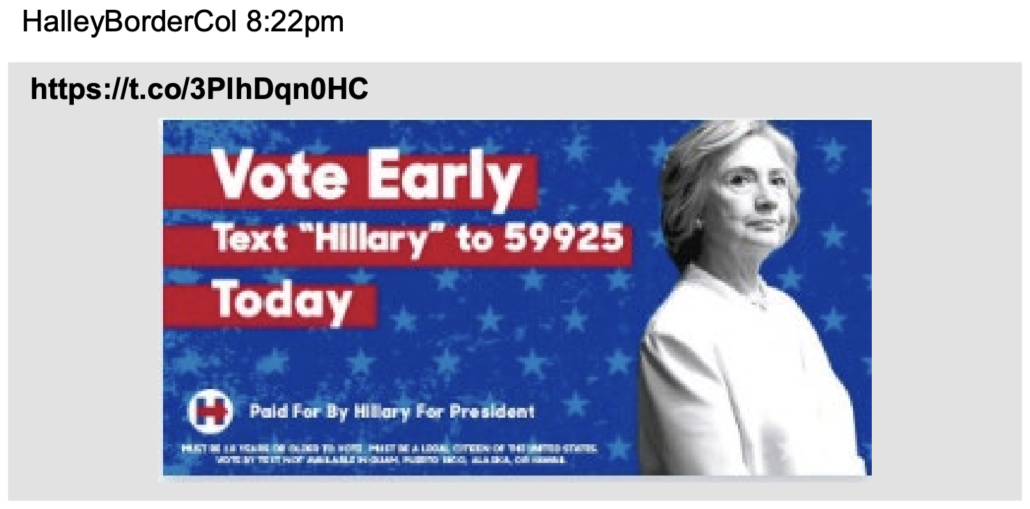

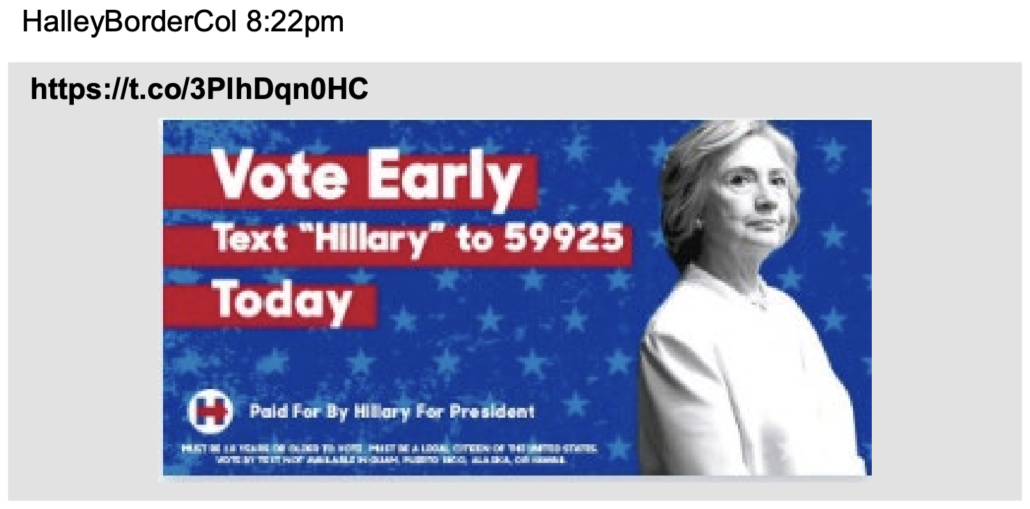

Then, two days later, HBC posted the first of the vote-by-text (as opposed to vote-by-hashtag) memes using the text number that allowed DOJ to track the reach of those that Mackey would send on November 2.

As far as is public, prosecutors never charged HBC, in spite of her key role in planning a “hoax” to suppress turnout, but perhaps that’s because she lives in a place where they spell “rumor” with a “u.”

In fact, DOJ didn’t even identify HBC as an unindicted co-conspirator in the complaint against Mackey, though it does describe her actions. The complaint names Anthime “Baked Alaska” Gionet as CC#1 (compare ¶17 of the complaint with this DM), Microchip as CC#2 (compare ¶25 of the complaint with this DM), a troll named NIA4_Trump who got temporarily suspended along with Mackey in November 2016 as CC#3, and a thus far unidentified troll named 1080p who was instrumental in tweaking the memes to more closely mimic Hillary’s graphics as CC#4 (compare ¶22a in the complaint with this DM).

By the time DOJ described the co-conspirators in a footnote to their February 24 filing, however, HBC was first on their list.

As was noted in the government’s initial motion in limine, the government alleges that individuals who posted, shared, or strategized over how to optimize the deceptive images or the messages therein are co-conspirators, and that the statements of those individuals are admissible as co-conspirator statements. These co-conspirators include the Twitter users identified in the Government’s Motion in Limine: @Halleybordercol, @WDFx2EU7, @UnityActivist, @Nia4_Trump, @1080p, @bakedalaska, @jakekass, @jeffytee, @curveme, 794213340545433604 and @Urpochan, the latter of which was described but not specifically identified as a co-conspirator in that submission. The materials provided to defense counsel on September 23, 2023 [sic] include statements from the following additional users which are of a similar character and admissible as co-conspirator statements: @WDFx2EU8, @MrCharlieCoker, @Donnyjbismarck, @unspectateur and 2506288844.

Note this footnote treats a second Microchip account as separate rather than identifying that it knew Microchip was behind both accounts using the same naming convention, “@WDFx2EU#.” This was the period after DOJ had informed Mackey, on February 13, which Twitter handles its cooperating witness had used but before DOJ had publicly revealed that it had a cooperating witness.

When it came to cross-examining Mackey on his claims to know nothing about these people, however, AUSA Erik Paulson prioritized HBC.

Q I’d like to ask you about some of people in that room.

A Okay.

Q Who is HalleyBorderCol?

A That’s someone I just know as HalleyBorderCol. I don’t know anything more about that person.

Q Nothing more?

A Yes.

[snip]

Mr. Mackey, do you remember this page?

A Yes.

Q HalleyBorderCol says: Let’s did depress illegal voter turnout with a nice hoax.

A Yes.

Q POTUSTrump says: I like that idea Haley, but I think we should wait for the day before or the day of, that way they don’t have time to debunk the rumor. Needs to be earlier than that.

The government’s identification of HBC in the complaint, or not, doesn’t matter legally. What mattered legally for the purpose of the trial was that Judge Ann Donnelly ruled the government had presented sufficient evidence of a conspiracy to treat HBC as one for the purposes of hearsay exception rules; Donnelly ruled that all the accounts listed above were.

But DOJ’s decision to charge Mackey alone, and to make Microchip plead guilty after a series of proffers as part of a cooperation agreement, suggests DOJ exercized discretion to treat HBC and a few other key players differently, even while both at trial and in the development of the offending meme she had a larger role.

She certainly had a larger role in the text-to-vote meme itself than Baked Alaska, for example.

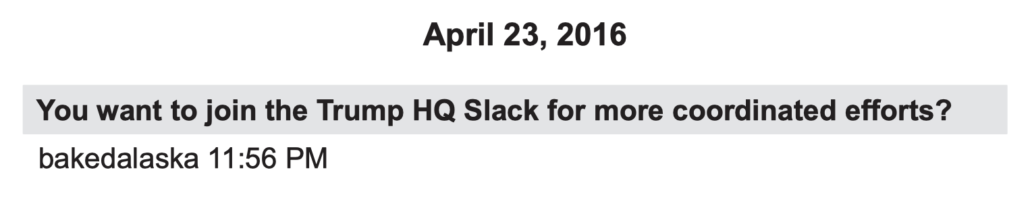

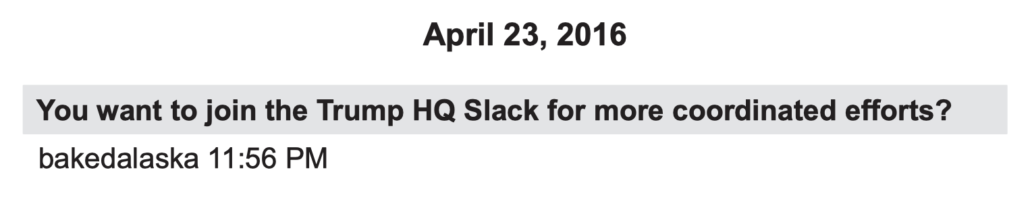

Baked Alaska is all over the trolling effort. He congratulates Mackey for being named the 107th most influential political tweeter of 2016, as everyone else did too, in March 2016. He warns against “roast[ing]” Bernie supporters, “cuz the more hatred they have for hillary the more likely they will join us in national or not vote at all,” in the same April 20, 2016 chat where he discusses the “new smart team” Trump has hired. On April 23, 2016, Baked Alaska asked Mackey via DM if he wanted to join the “Trump HQ Slack for more coordinated efforts?”

In May, Mackey asks for his help making #InTrumpsAmerica go viral. Baked Alaska boasts on July 24 that “we are controlling the narrative this is amazing.” In October, Gionet reminds other trolls to “make [minorities] hate hillary.”

At least as exhibited in the trial evidence, Baked Alaska’s sole overt act in the deceptive tweet involves instructing 1080p to “make a text message version of” the Tweet calling to vote remotely (it’s unclear whether Gionet calls 1080p or jeffytee “Gabe”). The tweets for which Mackey was convicted may have been his idea, but others executed the idea.

But it was enough for others to credit him with some responsibility for Trump’s win on November 9, 2016. “Tonight we meme’d reality,” Baked Alaska said after the win.

One more person’s role is of interest. Andrew Auernheimer — better known as Weev — was all over the earlier FedFreeHateChat, which came in for Mackey’s direct comments rather than as statements of co-conspirators. Weev seems to have spent the end of 2015 helping Mackey fine-tune his trolling skills. “Thanks to weev I am i[m]proving my rhetoric,” Mackey said in FFHC on November 19, 2015. “I just hope all this shitlording goes real life.”

Weev’s involvement is of particular interest because he was helping to run the Daily Stormer in pro-Russian territories. He was always one of the most obvious potential ties between Trump’s trolls and Russia. That’s one reason this paragraph, from the government’s motion in limine, reads very differently if you know “the Twitter user” in question is Weev.

On or about December 22, 2015, the defendant communicated with others in a Twitter direct-message group about sharing memes that would suggest certain voters were hiding their desire to vote for the defendant’s preferred Presidential candidate. The defendant stated, “it’s actually a great meme to spread, make all these shitlibs think they’re [sic] friends are secretly voting for Trump.” Several weeks later, on or about January 9, 2016, the defendant and another Twitter user discussed their Twitter methodologies. After the defendant stated that “Images work better than words,” the user stated “we should collaboratively work on a guide / like, step by step, each major aspect of the ideological disruption toolkit . . . ricky you could outline your methods of commentary / we could churn out a book like this, divide profits / and hand people a fucking manual for psychological loldongs terrorism.” The defendant responded “Yes… I think that would be good / I could do another chapter on methodologies from the ads industry– shit like my twitter ads stuff was very much the result of careful targeting, nobody’s managed to replicate it properly since.” Shortly thereafter, the Twitter user stated, “honestly at this point i’ve hand [sic] converted so many shitlibs that like, i am absolutely sure we can get anyone to do or believe anything as long as we come up with the right rhetorical formula and have people actually try to apply it consistently.” The defendant responded, “I think you’re right.”2 These statements, and those like them, are admissible and relevant to show, among other things, that the defendant’s intent in spreading memes was to influence people.

But Weev doesn’t appear, at least under the handle Rabite, after he celebrated the efficacy of the trolling on the day Trump sealed the nomination.

it’s fucking astonishing how much reach our little group here has between us, and it’ll solidify and grow after the general

“This is where it all started,” Mackey responded. But for Weev, that’s where his appearance in the trial evidence, under the moniker Rabite, at least, ended.

Weev’s absence — under his Rabite moniker, anyway — is all the more striking given that per a bench conference at trial, the search warrant specified that the specific meme Mackey ultimately sent out came from The Daily Stormer.

The search warrant also noted that the one that the defendant sent out was available on the Daily Stormer website, the American Nazi newspaper, as early as October 29, which is a couple days before the defendant did.

That is, Weev may have played a direct role in creating the meme in question. But unless he was posting under the moniker 1080p (who may have been referred to as “Gabe” by others), he was not credited with doing so in evidence presented at trial.

That differential treatment — and the changed focus on HBC in the trial as compared to the complaint — is one reason, but in no way the only reason, I’m interested in some other investigative details:

- Details about Microchip’s discussions with the government

- The timing of interviews with Hillary Clinton staffers and its disclosure to Mackey

- The decision not to call an investigative agent to the stand

According to a motion in limine dispute, an FBI agent named Jamie Dvorsky attempted to interview Mackey in Florida after his identity was disclosed in April 2018, which is when the FBI opened the case. Mackey first raised this issue on March 11 after he received materials on potential witnesses.

According to reports of FBI Special Agent Jamie Dvorsky, marked by the government as 3500-JAD-2 and 3500-JAD-17 (submitted under seal herewith), she and another agent traveled to Florida in 2018 and met Mr. Mackey at a Panera Bread in Boynton Beach. Mr. Mackey told her that he would be happy to speak to the agents if they would first contact his attorney, Richard Lubin. Mr. Lubin thereafter contacted Agent Dvorsky and said that Mr. Mackey would “100% cooperate and talk to the FBI.” Thereafter, Mr. Lubin did not contact the FBI nor return multiple calls.

When the government responded two days later, they described planning to call Dvorsky to explain how and when the FBI first opened the investigation.

As discussed with defense counsel, the government is calling Special Agent Dvorsky to testify as to when the government learned that the defendant was the user of the accounts that distributed the deceptive images and the initial investigative steps that were taken in the wake of that revelation. The chronology matters. As noted above, to the extent the defendant claims or suggests that the prosecution was somehow politically motivated, the fact that the government first identified the defendant in 2018 and began its investigation at that point is relevant in that regard. The government does not intend to elicit from Special Agent Dvorsky testimony that the defendant offered to cooperate with the FBI, but never followed through on the offer. Rather, to the extent that Agent Dvorsky will communicate the defendant’s statements at all, her testimony will be limited to the defendant’s telling her that he worked with Paul Nehlen.4 Accordingly, the limited testimony the government does intend to elicit is simply not prejudicial and does not warrant preclusion

They never did call her, though.

The FBI contacted Microchip, now their cooperating witness, around December 17, 2018 about a perceived threat he had made online in July 2018, but that may have been about a different case. Microchip then contacted Baked Alaska to inform him about the FBI visit, suggesting he has or had resilient ties to Baked Alaska.

Megan Rees, the FBI agent who ultimately obtained the arrest affidavit, was one of two FBI agents who visited Microchip’s home in December 2020, this time in conjunction with the Mackey case. When she wrote up that affidavit, she named Microchip, like Baked Alaska and 1080p, only as an unindicted co-conspirator.

But after Microchip saw that complaint, he reached out to the FBI via his lawyer.

Q Sir, my question to you is this: On February 4, 2021, did you reach out to Agent Rees and tell her that you had become aware that the person you knew as Ricky Vaughn had been arrested, and you believed you had information that would be useful to the FBI. Did you say that to Agent Rees?

[snip]

Q My first question is: When you reached out to Agent Rees on February 4, 2021, did you tell her that you had learned the person you knew as Ricky Vaughn had been arrested recently? Did you say that?

A Yes.

Q And in addition, did you tell her that you believed you had information that would be useful to the FBI?

A Correct.

Per his testimony on cross-examination, Microchip made a formal proffer around April 22, 2021.

At it, he claimed that the intent wasn’t so much to dissuade people from voting but just to push out as many messages as possible. He also claimed the chatrooms weren’t all that organized.

Q Sir, I’m going to ask you a question. Forgive the profanity in advance, but have you ever heard the term “shit posting”?

A Yes.

Q Do you recall telling the Government at this meeting that the focus was not on one message, it was on pushing out as many — as much content as possible?

[snip]

Q Do you recall telling the Government at that meeting that the participants in the chats were not as organized as many people believed?

A Yes, I remember saying that.

Q Do you recall telling the Government that there was no grand plan around stopping people from voting?

After several continuances and a revised memory of how organized things were, Microchip pled guilty on April 14, 2022. He had a meeting in advance of the disclosure of a cooperating witness on February 23, 2023. This post describes how Microchip testified to wanting to “infect” everything.

The timing of Microchip’s proffer is important, though, because it might explain any change in focus between the complaint and the evidence as presented at trial. That is, it might explain why prosecutors focused much more closely on HBC than Baked Alaska at trial.

But it also might explain any new investigative direction that DOJ took after first speaking with Microchip.

Mackey’s lawyer, Andrew Frisch (who has also represented VDARE), several times expressed curiosity about why the government used a summary FBI agent largely uninvolved in the case to introduce all the Twitter evidence, rather than putting the FBI agent who led the investigation, Megan Rees, on the stand.

MR. FRISCH: Can I put something on the record, unrelated to our prior conference. I intended at the close of the Government’s place to put a placeholder. But because of the way it worked, the jury was here, I couldn’t do it. I have been concerned as the trial has gone on that no case agent has testified. Maegan Rees didn’t testify, my friend Agent Granberg didn’t testify, and ultimately Agent Dvorsky did not testify. At one time or another. The key agent I’m concerned with is Agent Rees.

[snip]

MR. FRISCH: I’m mostly concerned about why no case agent testified and specifically whether there’s a reason, a bad reason, why Agent Rees’s 3500 has not been provided, obviously apart from when she attended Microchip interviews and things like that. I just wanted to put a placeholder, I’ll discuss it with the Government, I don’t want to hold things up. I wanted to register an objection at my earliest opportunity so if I can come back to it, if necessary.

[snip]

MR. FRISCH: I don’t know what she has, I don’t know what she said, I don’t know what’s in the reports. It’s just in my experience, it’s highly unusual that a trial happens without the case agent testifying, without any case agent testifying.

He’s not wrong, really, to question why the government didn’t use a case agent. Often, the government does so to keep someone who knows information inconvenient to the prosecution off the stand. For example, Durham may have used a paralegal in the Michael Sussmann case because the case agents had discovered some of Durham’s claims about the Alfa Bank anomaly were bullshit by the time of trial. Mueller used an agent focused on the obstruction part of the investigation in the Stone trial, who thereby could honestly say she didn’t know some of what DOJ subsequently discovered about Roger Stone’s actual ties to Russia when asked.

But it’s often (as it was in the Mueller investigation), done to hide parts of an ongoing investigation — something that a movement lawyer would surely have some interest in.

In this case, there are two obvious reasons to keep case agents off the stand.

The first is — as was revealed to Frisch after his opening argument — EDNY had a series of 18 interviews with Hillary’s campaign, between March 2021 and January 2023.

As Frisch laid out in a letter to the judge, after he opened, the government revealed those interviews, which, he claimed, he should have obtained.

The government’s second witness was Jess Morales Rocketto. On March 10, 2023, the Friday before the start of jury selection, the government first identified Ms. Rocketto as a witness. Thereafter, during jury selection, the government disclosed a report of the government’s then-recent interview of Ms. Rocketto, without disclosing any of eighteen reports of the government’s interviews of seventeen other representatives of the Clinton Campaign, conducted between March 2021 and January 2023. Ms. Rocketto testified that she was the Clinton Campaign’s digital organizing director; learned of vote-by-text memes using fake graphics during the final days of the campaign; found the memes’ misappropriation of the Clinton Campaign’s graphics and hashtag “#imwithher” to be such a “big deal” and so “jarring” that “you have to make a decision about what to do about something like this.” T 76, 78, 84-85, 90-92. See T 86 (The Court: “If you can avoid asking like terribly open-ended questions to this witness . . . . she has a lot to say, which is fine, but we’re never going to finish.”). On defense counsel’s subsequent cross-examination of Lloyd Cotler (a representative of the Clinton Campaign called principally to testify to steps to remediate the memes’ reference to a short code), defense counsel confirmed an unelaborated statement in the government’s report of Mr. Cotler’s interview that a Clinton Campaign worker named Amy Karr monitored social media, including 4chan [T 103], on which Mr. Mackey had seen the memes that he then shared.

The following morning, the government provided defense counsel with two reports of its interviews of Ms. Karr. At the lunch break, defense counsel requested that the government provide reports of all the government’s interviews of representatives of the Clinton Campaign. Highlights of the reports, summarized in the draft stipulation, contradicted the testimony and inferences elicited by the government from Ms. Rocketto and Mr. McNees. For example, Alexandria Witt, Senior Social Media Strategist, told the government that she referred vote-by-text memes to executive staff, but the general response was lackluster as though – – directly contradicting the very words used by Ms. Rocketto – – “this was no big deal.” Diana Al Ayoubi-Monett, another Senior Social Medical Strategist, said that she was mocked for taking “text-to-vote” memes seriously. Timothy Lu Hu Ball, a senior security expert, said that senior officials of the Clinton Campaign did not take the vote-by-texts seriously. Ms. Witt and Ms. Karr both were aware of and monitored “shit-posters” on social media supporting Clinton’s opponent. Memes containing misinformation about voting began to appear about three months before Election Day; there was no single influencer behind them; and senor staff, including campaign chair John Podesta, did not take concerns about the memes seriously. According to Matthew Compton, Deputy Digital Director (possibly Ms. Rocketto’s principal underling), the “#imwithher” hashtag had been somewhat commandeered with “unbelievable” amounts of irrelevant information, rendering it not “particularly useful.” Multiple witnesses told the government about records created by the campaign to track misinformation on social media (about which Mr. Mackey had been unaware and never attempted to subpoena or investigate). [my emphasis]

There’s no reason to believe these interviews were primarily pre-trial preparation. As the government explained in a bench conference, the government only handed them over after hearing what Mackey’s defense was in Frisch’s opening.

MR. PAULSEN: Your Honor, part of the reason we provided the 302s we did, is that we heard his opening argument, at the same time everyone did, and he made something like that argument. We turned them over at that point because it seemed like he was interested in that.

But even assuming Frisch’s description is accurate, what the Clinton campaign thought about Mackey’s trolling doesn’t change Mackey’s intent.

Which is what Judge Ann Donnelly ruled in the bench conference: this wasn’t Brady material, and besides, Frisch at that point still had several remedies available to him, such as calling the Hillary intern who identified some of the disinformation targeting Hillary on the dark web much earlier than anyone else.

THE COURT: Let me stop you there. I think I understand what you’re saying.

With respect to the issue — the e-mail telling people they could text to vote was not a big deal to the Clinton campaign. Why is that Brady material what their opinion of it is?

MR. FRISCH: Because they called Ms. Rocketto to essentially testify how horrible this was. How something had to be done right away. How she recognized this as a problem. That it specifically, in her view, was either targeted to or designed to affect or had the affect of effecting Latin American and African American voters. She was a terrific — she’s very charismatic and had a lot to say, that’s fine —

THE COURT: Why is someone —

MR. FRISCH: But I couldn’t cross-examine her with this information.

THE COURT: But you opened on it.

MR. FRISCH: But I didn’t know that the Clinton campaign agreed with my defense.

THE COURT: But who cares what their opinion is. The Clinton campaign can’t testify in court about what they think about something, any more than they can come — you didn’t object to it, she did say something was sneaky, I think I stopped her at some point. A particular person’s opinion of what the case is, I don’t understand how that is Brady material.

[snip]

[I]t’s the Court’s view that it’s not Brady material because it amounts to really, the essence is what the Clinton campaign thought about it, and that’s just not relevant. In fact, their opinion of it is no more valid than their opinion would be about whether Mr. Mackey is guilty or not. That’s not relevant, to the extent that’s the claim.

In his letter demanding an acquittal because of all this, Frisch explained that rather than calling any of these people as witnesses, he drafted a stipulation that the government rejected, which he then just emailed to Chambers.

Defense counsel emailed it to the Court (rather than electronically file it with a letter) when an issue unexpectedly arose early on the morning of the last day of trial about the government’s timely receipt of the draft stipulation; exigencies of the imminent trial day made preparation and filing of a letter impractical. But it would otherwise have been electronically filed to show that Mr. Mackey’s attempt at a mid-trial remedy for the government’s violation of Rule 5(f) and Brady had been rejected (though the government agreed to stipulate to a narrow portion thereof), thereby filling in the record and helping to show the consequent irreparable prejudice.

The letter mostly seems like a bid by a movement lawyer to turn the Mackey prosecution into the second coming of the Durham trial, an opportunity to investigate the victim of a bunch of malicious crimes in the 2016 election, in part to distract from the heinous things that Trump and his allies were doing.

All these interviews took place after the indictment and most presumably took place after Microchip first met with the government in April 2021.

Frisch seems uninterested in the obvious question presented by the revelation of 18 interviews with the Clinton campaign about disinformation targeting her 2016 campaign that went viral after being drafted on the dark web: Why EDNY was conducting these interviews, continuing well after any 5 year statute of limitations would have expired.

I don’t know the answer to that, but I bet the case agents do, which might be a good reason to keep them off the stand.

The other obvious reason to keep case agents off the stand has to do with knowledge of Microchip’s ongoing cooperation, which as the original motion revealing his cooperation describes, is something “beyond the scope” of this case.

In addition, since entering into the cooperation agreement, the CW has provided assistance to the FBI in other criminal investigations beyond the scope of this case. The CW is presently involved in multiple, ongoing investigations and other activities in which he or she is using assumed internet names and “handles” that do not reveal his or her true identity. The CW has not interacted with any witness, subject, or target in these investigations and activities on a face-to-face basis, and the government has no reason to think that the CW’s true identity has been compromised as a result of this work.

There’s no evidence that the ongoing interviews with the Clinton campaign about disinformation the dark web has to do with Microchip’s ongoing cooperation. There’s not even any evidence that the case agents in Mackey’s case are the ones he worked with subsequently; on the stand, he suggested he had not met with Agent Rees since his guilty plea.

Frisch’s job is to claim all this is about Douglass Mackey and it also likely serves his interests to drum up a false scandal about Hillary by publicly releasing these 302s.

But there’s a whole bunch of tangentially related issues that didn’t show up in this trial. There’s a bunch of this that isn’t about Douglass Mackey.