In this post, I noted that the notes from a March 6, 2017 meeting that Sussmann wants to introduce at trial might be a way to prove his claimed lie was not material.

But it gets far worse. In a filing explaining the basis for submitting the notes from that meeting — written by Tashina Gaushar, Mary McCord, and Scott Schools — Sussmann explained that the reason he didn’t include these notes in his motion in limine is because Durham only gave them to him in March, past his discovery deadline. When Durham provided this late discovery, Durham noted there were references to “a client” in some of the documents, without identifying where those references were.

That, Sussmann says, is a Brady violation.

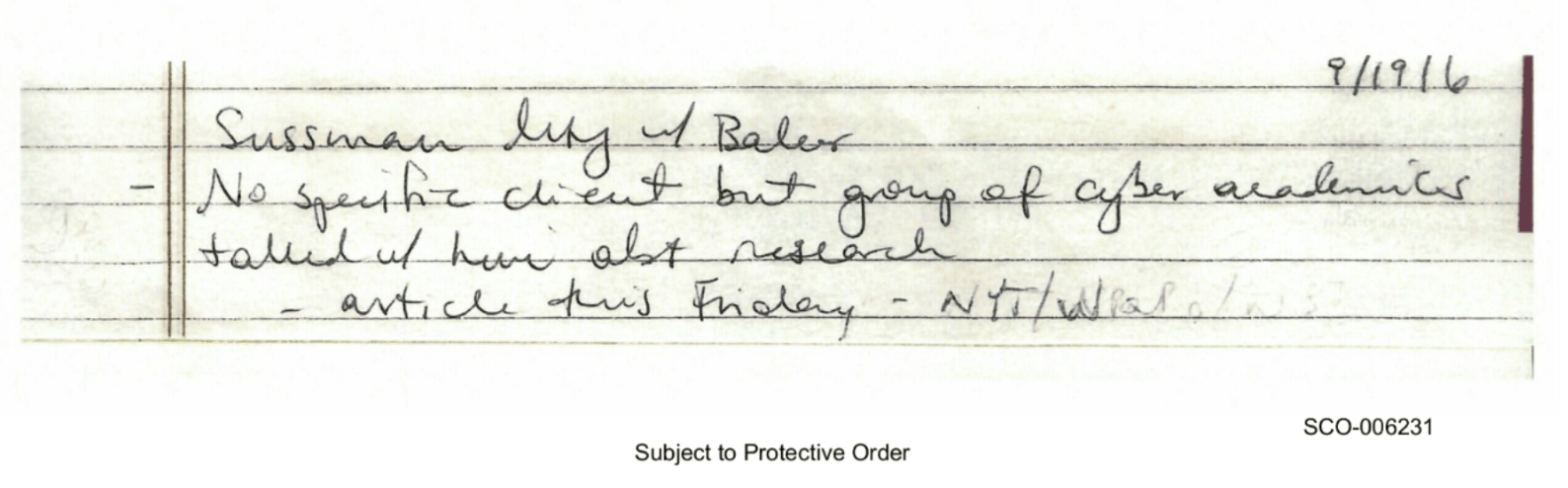

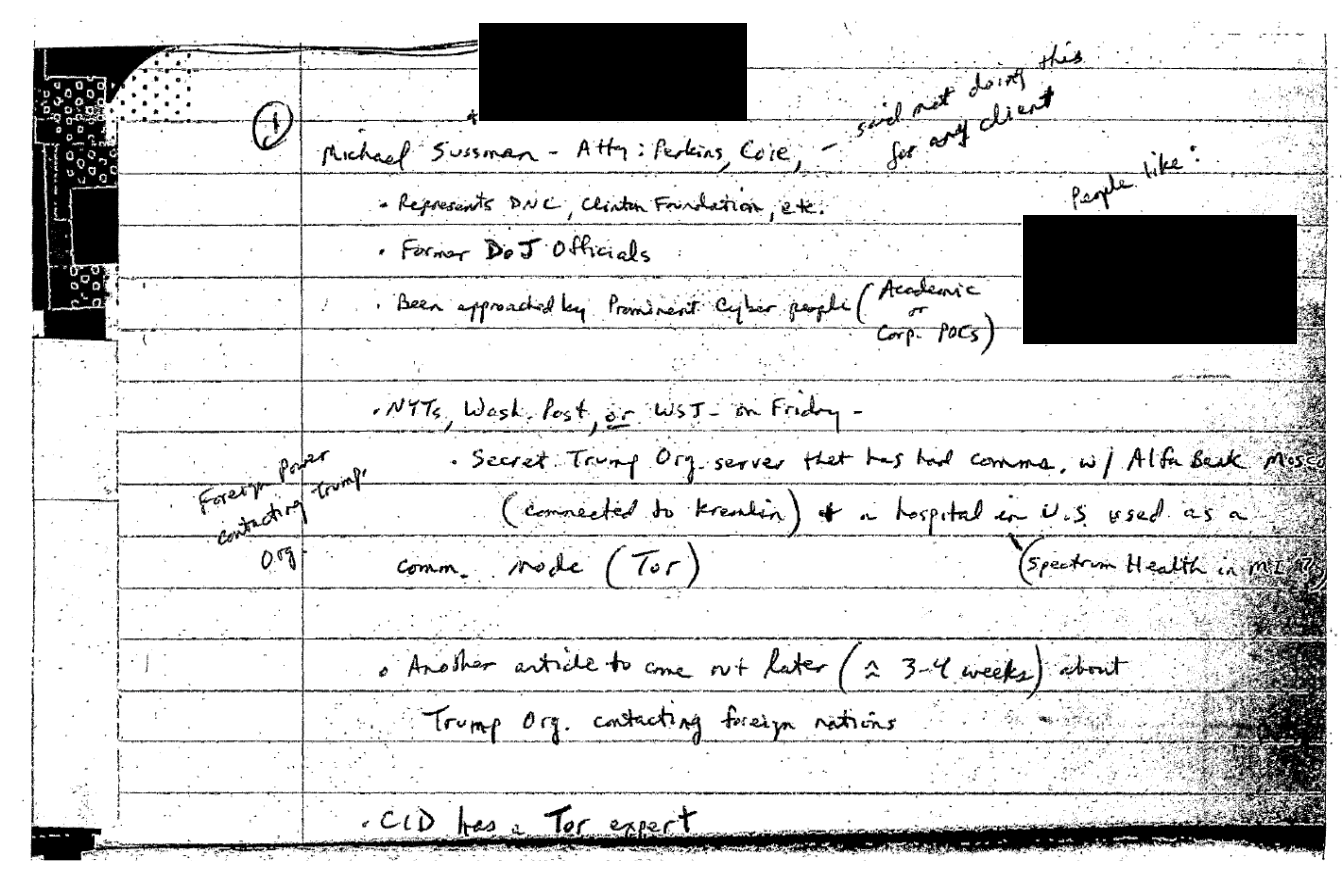

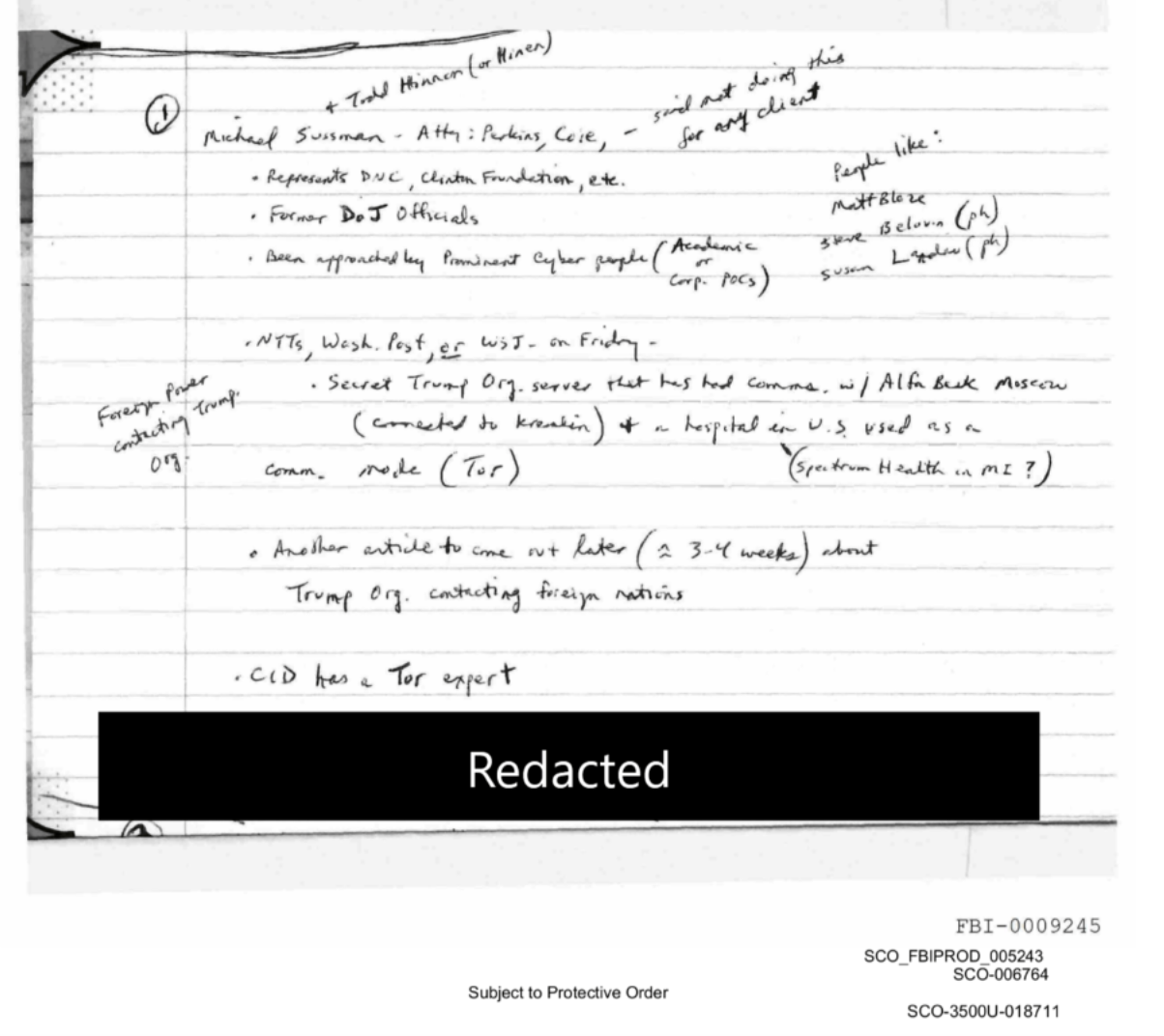

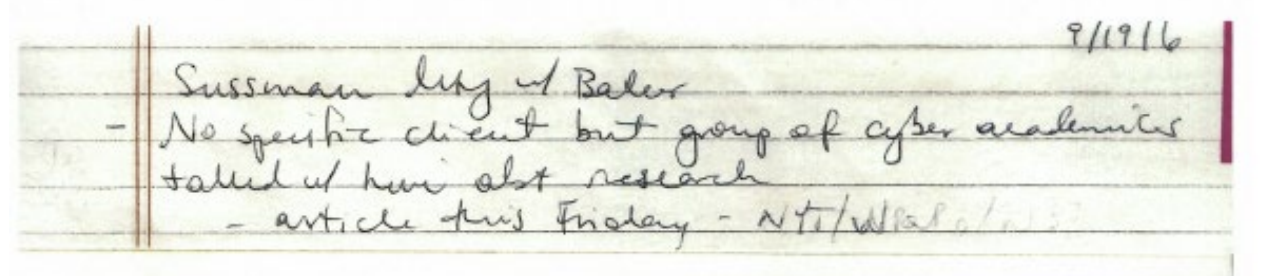

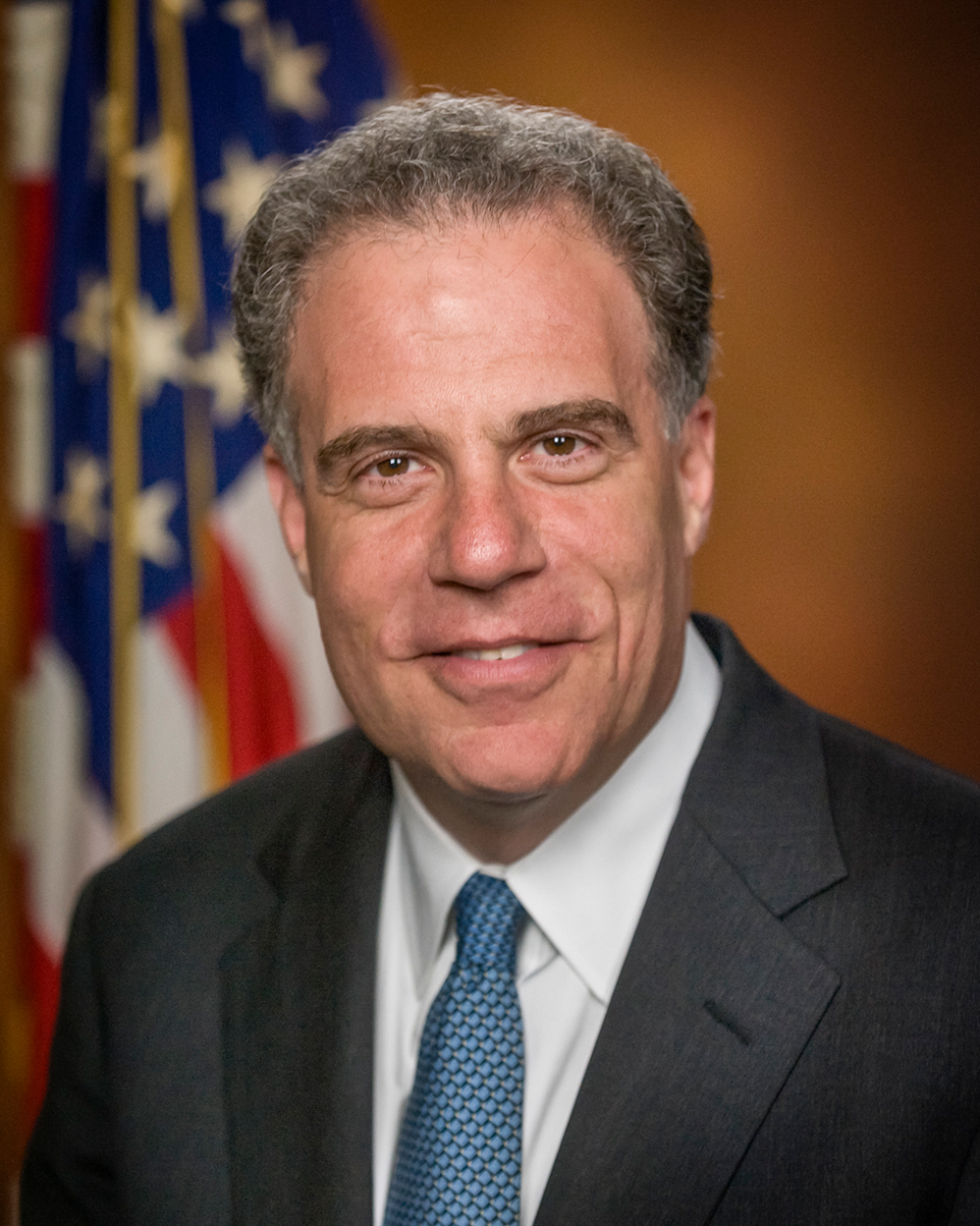

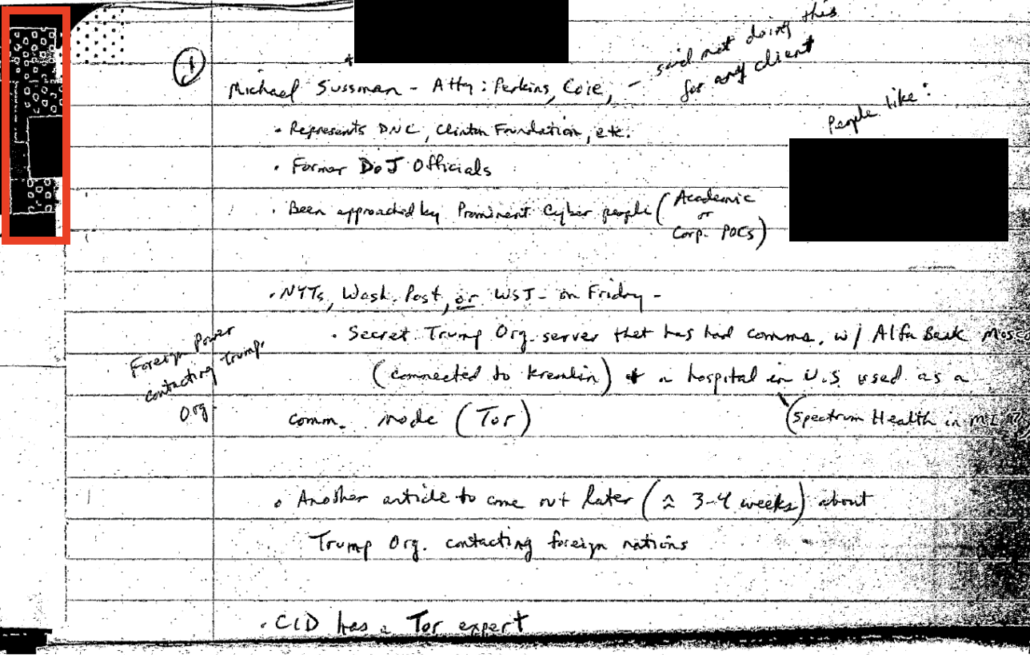

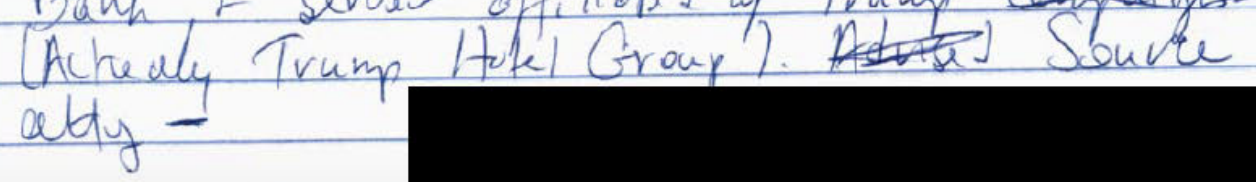

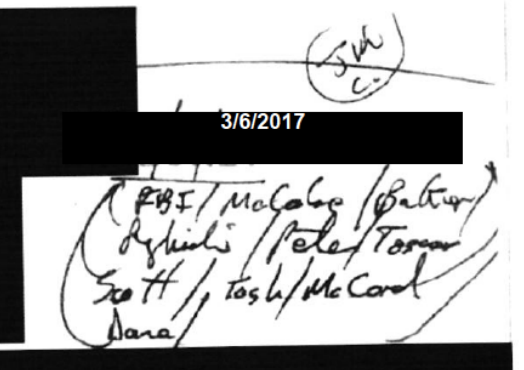

In late March 2022, the Special Counsel produced extraordinarily significant Brady material. See Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963). Specifically, the Special Counsel produced handwritten notes of several participants at a meeting held in March 2017, at which senior members of the FBI briefed DOJ’s Acting Attorney General about various aspects of the FBI’s investigation into potential Russian influence in the 2016 presidential election (“Russia Investigations”). During that meeting—at which James Baker (FBI General Counsel), Bill Priestap (Assistant Director of FBI’s Counterintelligence Division), and Trisha Anderson (FBI National Security & Cyber Law Branch Deputy General Counsel), among others, were present— Andrew McCabe (Deputy Director of FBI) described the FBI’s investigation of the Alfa Bank allegations. Specifically, Mr. McCabe stated that the Alfa Bank allegations were provided to the FBI by an attorney on behalf of his client. 2

[snip]

As a preliminary matter, we address the Special Counsel’s suggestion that Mr. Sussmann should have filed a motion in limine regarding the March 2017 Notes. The Special Counsel neglects to mention that these handwritten notes were buried in nearly 22,000 pages of discovery that the Special Counsel produced approximately two weeks before motions in limine were due. Specifically, the Special Counsel produced the March 2017 Notes as part of a March 18, 2022 production. The Special Counsel included the March 2017 Notes in a sub-folder generically labeled “FBI declassified” and similarly labeled them only as “FBI/DOJ Declassified Documents” in his cover letter. See Letter from J. Durham to M. Bosworth and S. Berkowitz (Mar. 18, 2022). And although the Special Counsel indicated on a phone call of March 18, 2022 that some of the 22,000 pages were documents that made references to “client,” he did not specifically identify the March 2017 Notes or otherwise call to attention to this powerful exculpatory material in the way that Brady and its progeny requires. See United States v. Hsia, 24 F. Supp. 2d 14, 29-30 (D.D.C. 1998) (“The government cannot meet its Brady obligations by providing [defendant] with access to 600,000 documents and then claiming that she should have been able to find the exculpatory information in the haystack. To the extent that the government knows of any documents or statements that constitute Brady material, it must identify that material to [defendant].”); United States v. Saffarinia, 424 F. Supp. 3d 46, 86 (D.D.C. 2020) (“[T]he government’s Brady obligations require it to identify any known Brady material to the extent that the government knows of any such material in its production of approximately 3.5 million pages of documents.”). All this aside, the Special Counsel has also failed to explain why this powerful Brady material was produced years into their investigation, six months after Mr. Sussmann was indicted, and only weeks before trial.3 Had the material been timely produced, Mr. Sussmann surely would have filed an appropriate motion in limine on the timeline for such motions.

3 In addition, the March 2017 Notes were produced over one month after the February 11, 2022 deadline for classified and declassified discovery, although they do not appear to fall within any of the categories of discovery for which the Special Counsel sought, and was granted, an extension to produce certain documents. See ECF No. 33, at 13-18.

Durham still hasn’t handed over all the notes from the meeting.

2 The defense has requested that the Special Counsel search for any additional records that may shed further light on the meeting and certain of those requests remain outstanding. To date, the Special Counsel has represented that the only additional notes from attendees at the meeting that he has identified do not reference whether or not Mr. Sussmann was acting on behalf of a client. The absence in those notes of any reference to whether Mr. Sussmann was acting on behalf of a client also raises questions regarding materiality of the charged conduct: if the on behalf of information were truly material to the FBI’s investigation, presumably all note takers would have written it down.

That he has not done so — and that the notes he did share appear unaltered — is significant because we know Jim Crowell also took notes, and it is virtually certain that Peter Strzok did too. Jeffrey Jensen redacted and added a date to the Crowell notes. Given that two sets of Strzok’s notes from related meetings were submitted in varying and altering form over the course of the Flynn litigation, who knows what happened to Strzok’s notes? McCabe was also a note-taker (though was the one speaking at the time).

In other words, Durham appears to be withholding notes from at least two people whose notes have been altered in the past.

Notably, the Crowell notes from the meeting were among those that Sidney Powell falsely claimed the withholding of which amounted to a Brady violation (and as I’ll show, these notes prove that claims made as part of the effort to blow up Mike Flynn’s prosecution were affirmatively false).

So Sussmann is credibly claiming a Brady violation (albeit not one that will get the case thrown out) over a set of notes that Flynn falsely claimed amounted to a Brady violation.

But as Sussmann argues, the late sharing of the notes is far more damning to Durham’s case.

Sussmann will present the notes, in part, to show that sometime after Sussmann sent James Baker a text on September 18, 2016 saying he wanted to help the FBI, Baker came to learn that he did have a client (and shared that information with Andy McCabe, who is the one who explained this at the meeting). When McCabe explained that in the March 6 meeting, neither Baker nor the people Durham will use to corroborate Baker’s credibility regarding his September 2016 representations corrected him.

And yet, at some point between September 18, 2016 and March 6, 2017, the FBI apparently came to believe that Mr. Sussmann did have a client in connection with his meeting with Mr. Baker, and that the Alfa allegations were provided “on behalf of his client.” The FBI could not have come to that belief based on conversations they had with Mr. Sussmann after his phone calls with Mr. Baker the week of September 19, 2016, because the FBI chose not to interview Mr. Sussmann about the information he provided to Mr. Baker, and the FBI chose not to ask Mr. Sussmann about or interview the cyber experts whom Mr. Sussmann identified as the source of the information he shared with the FBI.

Therefore, it is highly significant that, as of March 2017, when the FBI was asked to provide DOJ leadership with a summary of the Alfa Bank investigation (which by that time had concluded), the FBI at the highest levels described the Alfa Bank allegations as having come from an “attorney . . . on behalf of his client,” see Ex. A, Tashina Gauhar Notes, at SCO-074100, or from an attorney who had a client, but “d[id]/n[ot] say who [the] client was,” see Ex. B, Mary McCord Notes, at SCO-074070. The significance of the March 2017 Notes is further underscored by the fact that Mr. Baker, Mr. Priestap, and Ms. Anderson, all of whom are on the Special Counsel’s witness list, attended that March 2017 meeting. To the extent the Special Counsel argues, as the defense expects he will, that Mr. Baker’s recollection of the meeting has been “refreshed” by Mr. Priestap’s notes, it is obvious that the Special Counsel’s failure to refresh Mr. Baker’s recollection with the contradictory March 2017 Notes is relevant to Mr. Baker’s credibility as well as the manner in which the Special Counsel has handled a critical witness.

[snip]

At the briefing, as related to the Alfa Bank investigation, Mr. McCabe appears to have provided a general summary of the allegations that had been brought to the FBI. Most importantly, notes from other participants at the meeting indicate that Mr. McCabe explained that the allegations were brought to the FBI by an attorney “on behalf of his client,” see Ex. A, Tashina Gauhar Notes, at SCO-074100 (emphasis added), but that the attorney “d[id]/n[ot] say who [the] client was,” see Ex. B, Mary McCord Notes, at SCO-074070 (emphases added). There is no indication whatsoever from any participants’ notes that Mr. Baker—or Mr. Priestep or Ms. Anderson—refuted or corrected Mr. McCabe’s explanation. Such a statement—recorded by multiple participants, made in the presence of Mr. Baker, Mr. Priestep, and Ms. Anderson, and regarding the FBI meeting that is the subject of the charge against Mr. Sussmann—is both admissible and material to the defense.

The implication is that at some point very early in the investigation — either in their face-to-face September 19 meeting, or in calls on September 21 and 22 — Sussmann told Baker he did have a client. And Durham can’t prove when that was, because he has no original notes from Baker. At the very least, it proves that Sussmann wasn’t lying as part of a big cover-up. But it hurts Durham’s ability to prove the lie generally, because it’s possible he told Baker he wanted to help the FBI on September 18 (which is not charged), said nothing on September 19, and then explained he had a client on September 21 or 22.

Given the treatment of these and other notes from the same set, however, I’m more interested in Sussmann’s other argument: Durham chose to refresh Baker’s memory with Bill Priestap’s notes, but never showed him these.

In addition, as noted above, the Special Counsel apparently intends to elicit testimony suggesting that Mr. Baker landed on his latest version of events after reviewing notes from a separate meeting, taken by Mr. Priestap and provided to Mr. Baker by the Special Counsel. However, the Special Counsel conspicuously did not show Mr. Baker the March 2017 Notes when attempting to refresh his recollection. The March 2017 Notes are thus also admissible to attack the Special Counsel’s prejudicial handling of a critical witness, as well as Mr. Baker’s current recollection of events. See United States v. Fieger, No. 07-CR- 20414, 2008 WL 996401, at *2-3 (E.D. Mich. Apr. 8, 2008) (defendants permitted to “bring in the factual scenario” of the government’s investigation, including by “asking witnesses about the circumstances surrounding their questioning by Government agents”).

That is, he was coaching Baker to tell him the story he needed to be true and suppressing the story that Baker had already told publicly for which Durham had corroboration.

The most likely explanation is that Baker learned (and shared) that Sussmann had a client in one of the September calls, and the conflicting stories explain why Baker’s story has been so inconsistent. Ultimately, though, if Sussmann told Baker he had a client within days, it says he didn’t originally (in a September 18 text that was not charged) claim he was coming to help the FBI as part of a big cover-up. He did so because he wanted to help the FBI and then, within a week, proceeded to do so.

Here’s the thing: From the start, I’ve been expecting Durham to have real discovery problems (and, given that he’s slow-walking on turning over Crowell’s known and Strzok’s likely notes, will continue to have such problems here).

But he has no excuse with these notes. They’re notes he would have reviewed closely in 2020. These are in no way notes he couldn’t have known about. They’re not even notes that the Ukraine invasion would have created a delay in reviewing; the primary classified information in the notes pertains to Walid Phares, who was investigated for his ties to Egypt, not Russia.

These are the notes he was ordered to make a case out of. He had and reviewed them before he started hunting Michael Sussmann.

And yet he chose not to use the documents that hurt his case to refresh Baker’s memory and then buried them in a stack of tardy discovery.

Update: Intro and close fixed.