The Mueller Filing

Robert Mueller’s team has submitted its response to Paul Manafort’s motion to dismiss his indictment based on a claim Mueller isn’t authorized to prosecute crimes like the money laundering he is accused of. As I predicted, this filing lays out some theory of his case — but much of it is redacted, in the form of a memo Rod Rosenstein wrote last August laying out the parameters of the investigation at that time. As the filing makes clear, that memo (and any unmentioned predecessors or successors) form the same function as the public memos Jim Comey gave Patrick Fitzgerald to memorialize any seeming expansions of his authority in the CIA leak case, which the DC Circuit relied on to determine that the Libby prosecution was clearly authorized by Fitzgerald’s mandate.

Nevertheless, midway through the legal description, the filing lays out what I have — Manafort’s Ukrainian entanglements are part of this investigation because 1) he was a key player in the campaign and 2) had long ties to Russian backed politicians and (this is a bit trickier) Russians like Oleg Deripaska.

The Appointment Order itself readily encompasses Manafort’s charged conduct. First, his conduct falls within the scope of paragraph (b)(i) of the Appointment Order, which authorizes investigation of “any links and/or coordination between the Russian government and individuals associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump.” The basis for coverage of Manafort’s crimes under that authority is readily apparent. Manafort joined the Trump campaign as convention manager in March 2016 and served as campaign chairman from May 2016 until his resignation in August 2016, after reports surfaced of his financial activities in Ukraine. He thus constituted an “individual associated with the campaign of President Donald Trump.” Appointment Order ¶ (b) and (b)(i). He was, in addition, an individual with long ties to a Russia-backed Ukrainian politician. See Indictment, Doc. 202, ¶¶ 1-6, 9 (noting that between 2006 and 2015, Manafort acted as an unregistered agent of Ukraine, its former President, Victor Yanukovych—who fled to Russia after popular protests—and Yanukovych’s political party). Open-source reporting also has described business arrangements between Manafort and “a Russian oligarch, Oleg Deripaska, a close ally of President Vladimir V. Putin.”

[snip]

The Appointment Order is not a statute, but an instrument for providing public notice of the general nature of a Special Counsel’s investigation and a framework for consultation between the Acting Attorney General and the Special Counsel. Given that Manafort’s receipt of payments from the Ukrainian government has factual links to Russian persons and Russian-associated political actors, and that exploration of those activities furthers a complete and thorough investigation of the Russian government’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 election and any links and/or coordination with the President’s campaign, the conduct charged in the Indictment comes within the Special Counsel’s authority to investigate “any matter that arose or may arise directly from the investigation.”

I’ll do a follow-up on why the Deripaska reference is a bit tricky. It’s tricky in execution, not in fact.

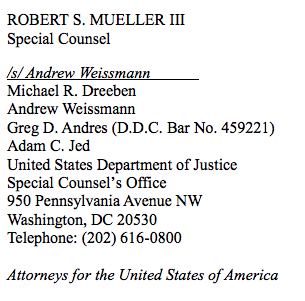

The “Attorneys for the United States of America”

I’ll refer to the author of this memo as Mueller for convenience sake, but because I obsess about how Mueller’s team deploys, it’s worth noting how the memo is signed.

The memo is signed by Andrew Weissman, the lead in the Manafort prosecution and (as the memo notes) a career AUSA in his own right. Greg Andres, who has also been on all the Manafort filings, includes his DC district license, making any continuity there clear. Adam Jed, an appellate specialist who has been deployed to this team in the past, is included. But before all them is Michael Dreeben, the Solicitor General’s killer attorney on appeals.

Aside from Mueller himself, Andres is the only lawyer listed who was not a DOJ employee when Jim Comey got fired, which is relevant given the memo’s argument that these attorneys could have prosecuted this with or without Mueller present.

Notably, Kyle Freeny, who has been on all the other Manafort filings, is not listed.

I’m unsure whether the filing uses the title, “Attorneys for the United States of America” because it underscores the argument of the memo — all their authority derives directly from Rosenstein — or if it signifies someone (probably Dreeben, who maintains his day job at the Solicitor General’s office) isn’t actually a formal member of Mueller’s team. But it is a departure from the norm, which since at least the roll-out of Brian Richardson as a “Assistant Special Counsel” with the Van der Zwaan plea, has used the titles “Senior” and “Assistant Special Counsel” to sign their filings.

Update: Christian Farias notes that this Attorneys for the US is not unique to this filing.

Manafort is especially screwed because Rosenstein is so closely involved

The memo starts by laying out what its presents as the history of the investigation. It includes the following events:

- Jeff Sessions March 2, 2017 recusal

- Jim Comey’s March 20, 2017 public confirmation of an investigation into “the Russian government’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 presidential election, and that includes investigating the nature of any links between individuals associated with the Trump campaign and the Russian government and whether there was an coordination between the campaign and Russia’s efforts.”

- Rod Rosenstein’s May 17, 2017 order appointing Mueller Special Counsel “to investigate Russian interference with the 2016 presidential election and related matters”

It then lays out the regulatory framework governing Mueller’s appointment. While this generally maps what Rosenstein included in his appointment order — which cites 28 USC §§ 509, 510, 515, and 600.4 through 600.10 — Mueller also cites to the basis of the Attorney General’s authority, including 28 USC §§ 503, 516, and all of 600. The latter citation is of particular interest, as it notes that the AG (Rosenstein, in this case) ” is not required to invoke the Special Counsel regulations” (which the filing backs by citing some historical examples). The filing then asserts that the Special Counsel regulations serve as ” a helpful framework for the Attorney General to use in establishing the Special Counsel’s role.”

Mueller then describes what the filing implies has been the process by which Mueller has informed Rosenstein of major actions he’s about to take. This consists of “‘providing Urgent Reports’ to Department leadership on ‘major developments.'” By doing it this way, Mueller implies a process without providing a basis to FOIA these Urgent Reports.

Then, the filing lays out how the scope of his authority has evolved. Initially, he notes, that was based on his appointing order. On August 2 — two and a half months after his appointment, almost a week after George Papadopoulos’ arrest, and the day after Andres joined Mueller’s team — Rosenstein wrote a memo describing the scope of Mueller’s investigation and authority. That memo (which is included in heavily redacted form) authorizes Mueller to investigate,

Allegations that Paul Manafort:

- Committed a crime or crimes by colluding with Russian government officials with respect to the Russian government’s efforts to interfere with the 2016 election for President of the United States, in violation of United States law;

- Committed a crime or crimes arising out of payments he received from the Ukrainian government before and during the tenure of President Viktor Yanukovych.

In other words, by August 2 (if not before) Rosenstein had authorized Mueller to prosecute Manafort for the money laundering of his payments from Yanukovych.

Significantly, the filing notes that the August 2 memo told Mueller to come back if anything else arises.

For additional matters that otherwise may have arisen or may arise directly from the Investigation, you should consult my office for a determination of whether such matters should be within the scope of your authority. If you determine that additional jurisdiction is necessary in order to fully investigate and resolve the matters assigned, or to investigate new matters that come to light in the course of your investigation, you should follow the procedures set forth in 28 C.F.R. § 600.4(b).

The filing then lays out Manafort’s DC indictments and his challenge to Mueller’s authority. The summary of that argument looks like this:

Manafort’s motion to dismiss the Indictment should be rejected for four reasons. First, the Acting Attorney General and the Special Counsel have acted fully in accordance with the relevant statutes and regulations. The Acting Attorney General properly established the Special Counsel’s jurisdiction at the outset and clarified its scope as the investigation proceeded. The Acting Attorney General and Special Counsel have engaged in the consultation envisioned by the regulations, and the Special Counsel has ensured that the Acting Attorney General was aware of and approved the Special Counsel’s investigatory and prosecutorial steps. Second, Manafort’s contrary reading of the regulations—implying rigid limits and artificial boundaries on the Acting Attorney General’s actions—misunderstands the purpose, framework, and operation of the regulations. Properly understood, the regulations provide guidance for an intra-Executive Branch determination, within the Department of Justice, of how to allocate investigatory and prosecutorial authority. They provide the foundation for an effective and independent Special Counsel investigation, while ensuring that major actions and jurisdictional issues come to the Acting Attorney General’s attention, thus permitting him to fulfill his supervisory role. Accountability exists for all phases of the Special Counsel’s actions. Third, that understanding of the regulatory scheme demonstrates why the Special Counsel regulations create no judicially enforceable rights. Unlike the former statutory scheme that authorized court-appointed independent counsels, the definition of the Special Counsel’s authority remains within the Executive Branch and is subject to ongoing dialogue based on sensitive prosecutorial considerations. A defendant cannot challenge the internal allocation of prosecutorial authority under Department of Justice regulations. Finally, Manafort’s remedial claims fail for many of the same reasons: the Special Counsel has a valid statutory appointment; this Court’s jurisdiction is secure; no violation of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure occurred; and any rule-based violation was harmless. [my emphasis]

The bolded bit is the key part: Mueller is treating Manafort’s challenge as a challenge to Article II authority, making the appointment even more sound than previous Ken Starr-type Independent Counsel appointments were, because they don’t present a constitutional appointments clause problem. Mueller returns to that argument several times later in the filing.

Under the Independent Counsel Act, constitutional concerns mandated limitations on the judiciary’s ability to assign prosecutorial jurisdiction. In the wholly Executive-Branch regime created by the Special Counsel regulations, those constitutional concerns do not exist.

[snip]

[T]he court contrasted [limitations on Independent Counsels] with the Attorney General’s “broader” authority to make referrals to the independent counsel: the Attorney General “is not similarly subject to the ‘demonstrably related’ limitation” because the Attorney General’s power “is not constrained by separation of powers concerns.” Id.; see also United States v. Tucker, 78 F.3d 1313, 1321 (8th Cir.), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 820 (1996). That is because the Attorney General’s referral decision exercises solely executive power and does not threaten to impair Executive Branch functions or impose improper duties on another branch.

[snip]

It is especially notable that Manafort, while relying on principles of political accountability, does not invoke the Appointments Clause as a basis for his challenge, despite the Clause’s “design[] to preserve political accountability relative to important Government assignments.” E

From there, the memo goes into the legal analysis which is unsurprising. The courts, including the DC Circuit in the Libby case, have approved this authority. That’s a point the filing makes explicit by comparing the August 2 memo with the two memos Jim Comey wrote to document the scope of Patrick Fitzgerald’s authority in the CIA leak investigation.

The August 2 Scope Memorandum is precisely the type of material that has previously been considered in evaluating a Special Counsel’s jurisdiction. United States v. Libby, 429 F. Supp. 2d 27 (D.D.C. 2006), involved a statutory and constitutional challenge to the authority of a Special Counsel who was appointed outside the framework of 28 C.F.R. Part 600. In rejecting that challenge, Judge Walton considered similar materials that defined the scope of the Special Counsel’s authority. See id. at 28-29, 31-32, 39 (considering the Acting Attorney General’s letter of appointment and clarification of jurisdiction as “concrete evidence * * * that delineates the Special Counsel’s authority,” and “conclud[ing] that the Special Counsel’s delegated authority is described within the four corners of the December 30, 2003 and February 6, 2004 letters”). The August 2 Scope Memorandum has the same legal significance as the original Appointment Order on the question of scope. Both documents record the Acting Attorney General’s determination on the scope of the Special Counsel’s jurisdiction. Nothing in the regulations restricts the Acting Attorney General’s authority to issue such clarifications.

Having laid out (with the Rosenstein memo) that this investigation operates in equivalent fashion to the Libby prosecution, the case is fairly well made. Effectively Manafort is all the more screwed because the Acting AG has been personally involved and approved each step.

The other authorities cover other prosecutions Mueller has laid out

The filing is perhaps most interesting for the other authorities casually asserted, which are not necessarily directly relevant in this prosecution, but are for others. First, Mueller includes this footnote, making it clear his authority includes obstruction, including witness tampering.

The Special Counsel also has “the authority to investigate and prosecute federal crimes committed in the course of, and with intent to interfere with, the Special Counsel’s investigation, such as perjury, obstruction of justice, destruction of evidence, and intimidation of witnesses” and has the authority “to conduct appeals arising out of the matter being investigated and/or prosecuted.” 28 C.F.R. § 600.4(a). Those authorities are not at issue here.

Those authorities are not at issue here, but they are for the Flynn, Papadopoulos, Gates, and Van der Zwaan prosecutions, and for any obstruction the White House has been engaging in. But because it is relevant for the Gates and Van der Zwaan prosecutions, that mention should preempt any Manafort attempt to discredit their pleas for the way they expose him.

The filing includes a quotation from DOJ’s discussion of special counsels making it clear that it’s normal to investigate crimes that might lead someone to flip.

[I]n deciding when additional jurisdiction is needed, the Special Counsel can draw guidance from the Department’s discussion accompanying the issuance of the Special Counsel regulations. That discussion illustrated the type of “adjustments to jurisdiction” that fall within Section 600.4(b). “For example,” the discussion stated, “a Special Counsel assigned responsibility for an alleged false statement about a government program may request additional jurisdiction to investigate allegations of misconduct with respect to the administration of that program; [or] a Special Counsel may conclude that investigating otherwise unrelated allegations against a central witness in the matter is necessary to obtain cooperation.”

That one is technically relevant here — one thing Mueller is doing with the Manafort prosecution (and successfully did with the Gates one) is to flip witnesses against Trump. But it also makes it clear that Mueller could do so more generally.

I’ll comment more on the memo tomorrow. But for now, understand this is a solid memo that puts the Manafort prosecution squarely on the same footing that the Libby one was.