Because of Joe Biggs’ role at the nexus between the mob that attacked Congress and those that orchestrated the mob, his prosecution is the most important case in the entire January 6 investigation. If you prosecute him and his alleged co-conspirators successfully, you might also succeed in holding those who incited the attack on the Capitol accountable. If you botch the Biggs prosecution, then all the most important people will go free.

Which is why it is so unbelievable that DOJ put someone who enabled Sidney Powell’s election season lies about the Mike Flynn prosecution, Jocelyn Ballantine, on that prosecution team.

Yesterday, at the beginning of the Ethan Nordean and Joe Biggs hearing, prosecutor Jason McCullough told the court that in addition to him and Luke Jones, Ballantine was present at the hearing for the prosecution. He may have said that she was “overseeing” this prosecution. (I’ve got a request for clarification in with the US Attorney’s office.)

Ballantine has not filed a notice of appearance in the case (nor does she show on the minute notice for yesterday’s hearing). In the one other January 6 case where she has been noticeably involved — electronically signing the indictment for Nick Kennedy — she likewise has not filed a notice of appearance.

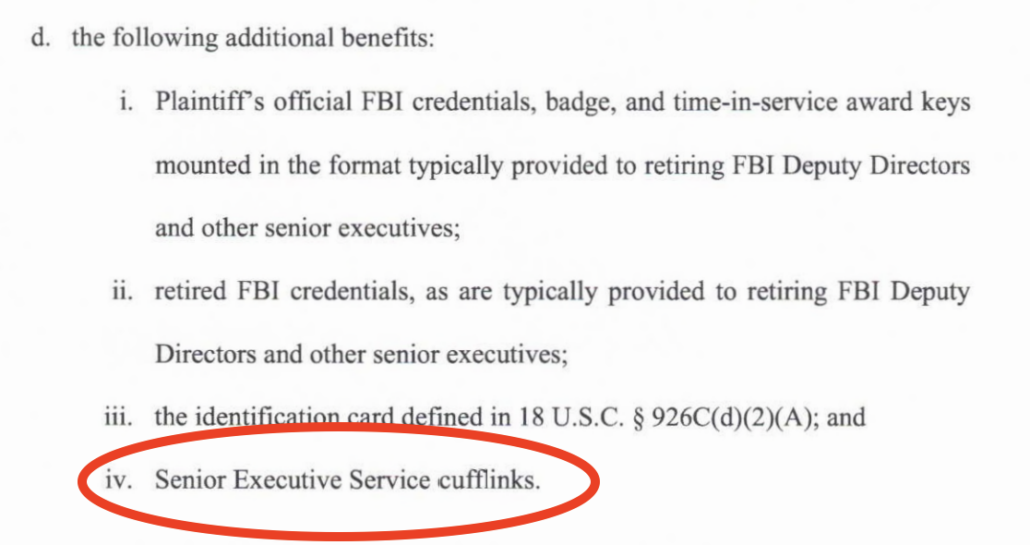

Less than a year ago when she assisted in DOJ’s attempts to overturn the Mike Flynn prosecution, Ballantine did three things that should disqualify her from any DOJ prosecution team, much less serving on the most important prosecution in the entire January 6 investigation:

- On September 23, she provided three documents that were altered to Sidney Powell, one of which Trump used six days later in a packaged debate attack on Joe Biden

- On September 24, she submitted an FBI interview report that redacted information — references to Brandon Van Grack — that was material to the proceedings before Judge Emmet Sullivan

- On October 26, she claimed that lawyers for Peter Strzok and Andrew McCabe had checked their clients’ notes to confirm there were no other alterations to documents submitted to the docket; both lawyers refused to review the documents

After doing these things in support of Bill Barr’s effort to undermine the Flynn prosecution (and within days of the Flynn pardon), Ballantine was given a confidential temporary duty assignment (it may have been a CIA assignment). Apparently she’s back at DC USAO now.

Three documents got altered and another violated Strzok and Page’s privacy

As a reminder, after DOJ moved to hold Mike Flynn accountable for reneging on his plea agreement, Billy Barr put the St. Louis US Attorney, Jeffrey Jensen, in charge of a “review” of the case, which DOJ would later offer as its excuse for attempting to overturn the prosecution.

On September 23, Ballantine provided Powell with five documents, purportedly from Jensen’s investigation into the Flynn prosecution:

I outlined the added date on the first set of Strzok notes here:

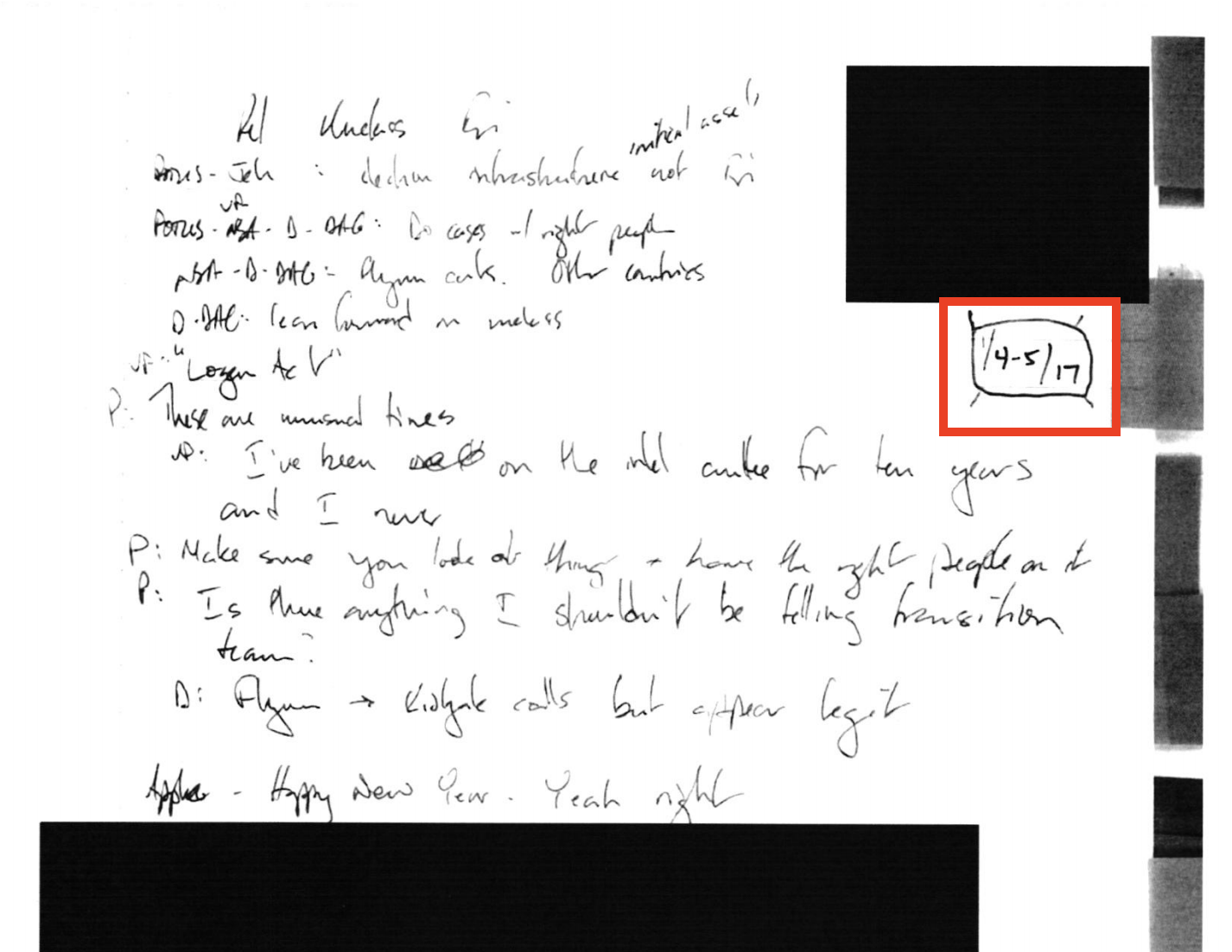

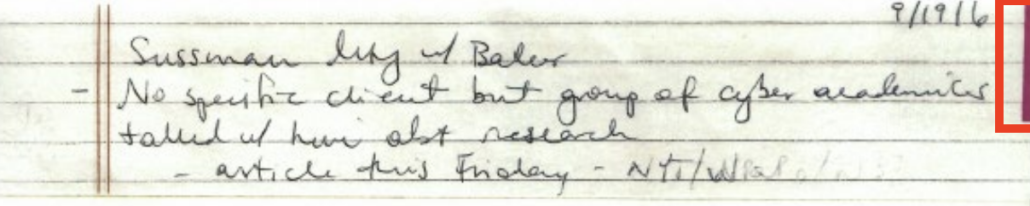

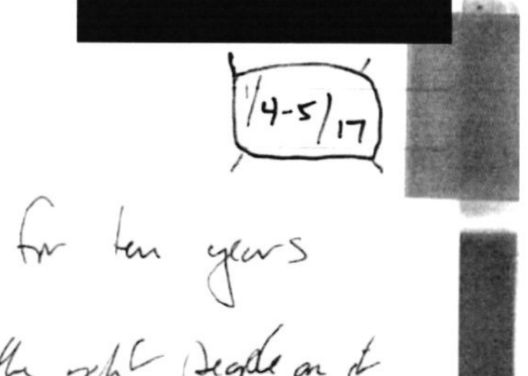

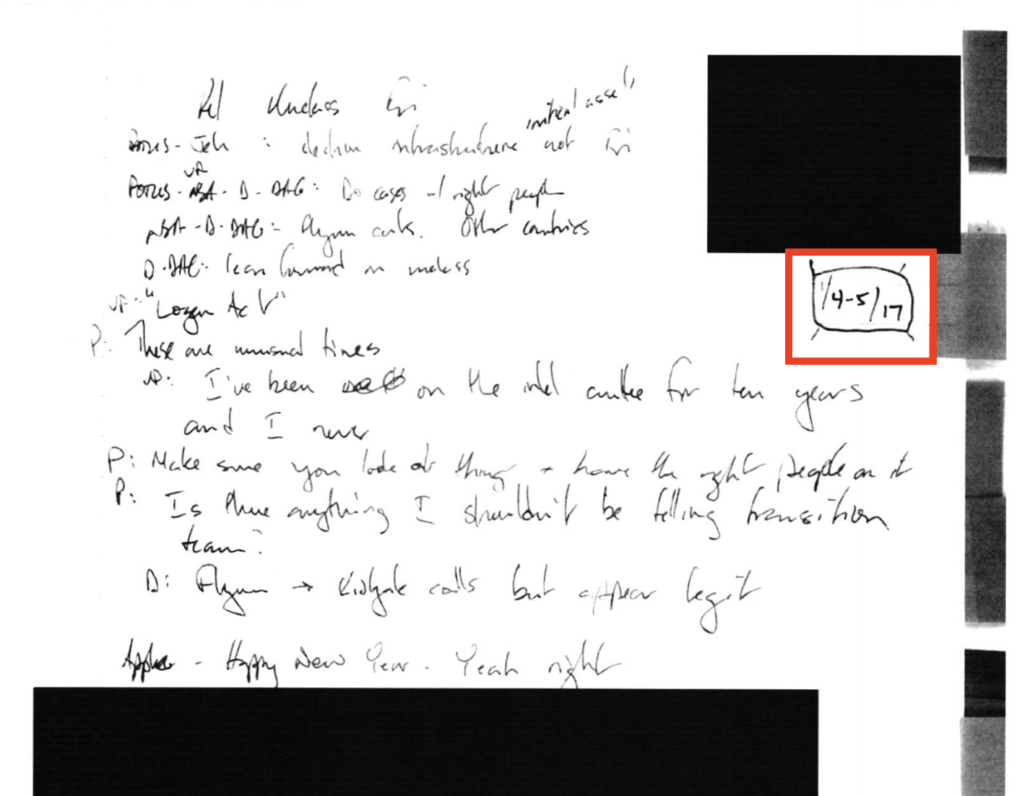

There was never any question that the notes could have been taken no earlier than January 5, because they memorialized Jim Comey’s retelling of a meeting that other documentation, including documents submitted in the Flynn docket, shows took place on January 5. Even Chuck Grassley knows what date the meeting took place.

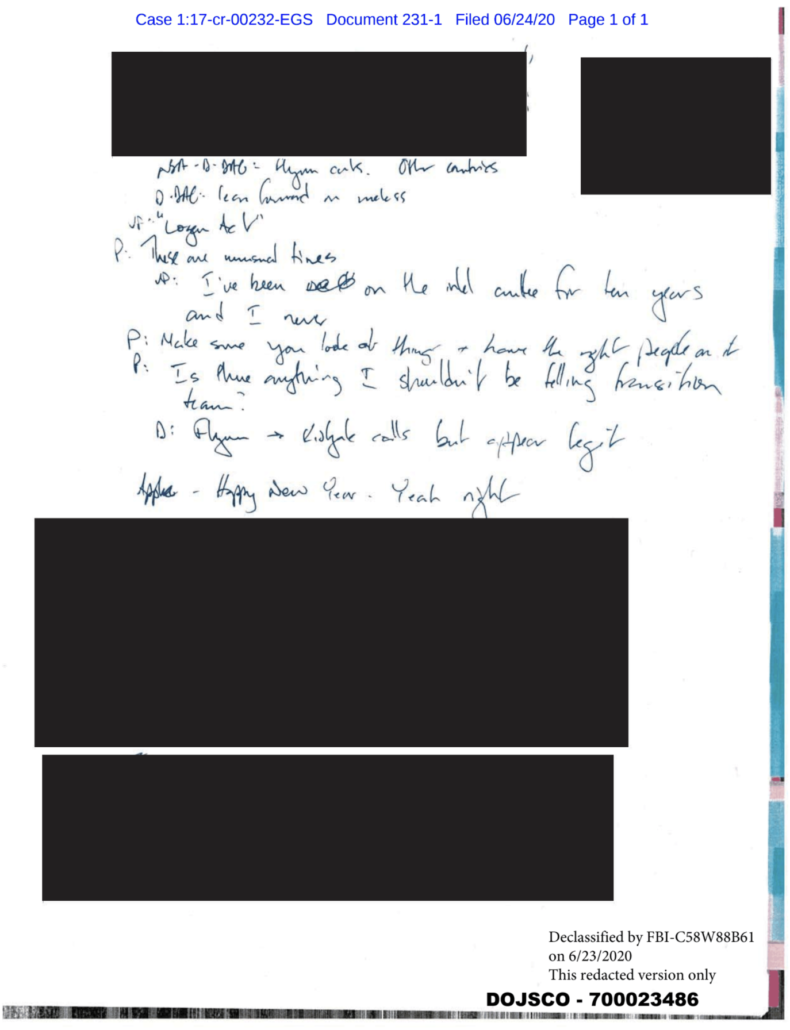

But DOJ, while using the notes as a central part of their excuse for trying to overturn the Flynn prosecution, nevertheless repeatedly suggested that there was uncertainty about the date of the notes, claiming they might have been taken days earlier. And then, relying on DOJ’s false representations about the date, Sidney Powell claimed they they showed that Joe Biden — and not, as documented in Mary McCord’s 302, Bob Litt — was the one who first raised the possibility that Flynn may have violated the Logan Act.

Strzok’s notes believed to be of January 4, 2017, reveal that former President Obama, James Comey, Sally Yates, Joe Biden, and apparently Susan Rice discussed the transcripts of Flynn’s calls and how to proceed against him. Mr. Obama himself directed that “the right people” investigate General Flynn. This caused former FBI Director Comey to acknowledge the obvious: General Flynn’s phone calls with Ambassador Kislyak “appear legit.” According to Strzok’s notes, it appears that Vice President Biden personally raised the idea of the Logan Act.

During the day on September 29, Powell disclosed to Judge Sullivan that she had spoken to Trump (as well as Jenna Ellis) about the case. Then, later that night, Trump delivered a prepared attack on Biden that replicated Powell’s false claim that Biden was behind the renewed investigation into Flynn.

President Donald J. Trump: (01:02:22)

We’ve caught them all. We’ve got it all on tape. We’ve caught them all. And by the way, you gave the idea for the Logan Act against General Flynn. You better take a look at that, because we caught you in a sense, and President Obama was sitting in the office.

In a matter of days, then, what DOJ would claim was an inadvertent error got turned into a campaign attack from the President.

When DOJ first confessed to altering these notes, they claimed all the changes were inadvertent.

In response to the Court and counsel’s questions, the government has learned that, during the review of the Strzok notes, FBI agents assigned to the EDMO review placed a single yellow sticky note on each page of the Strzok notes with estimated dates (the notes themselves are undated). Those two sticky notes were inadvertently not removed when the notes were scanned by FBI Headquarters, before they were forwarded to our office for production. The government has also confirmed with Mr. Goelman and can represent that the content of the notes was not otherwise altered.

Similarly, the government has learned that, at some point during the review of the McCabe notes, someone placed a blue “flag” with clear adhesive to the McCabe notes with an estimated date (the notes themselves are also undated). Again, the flag was inadvertently not removed when the notes were scanned by FBI Headquarters, before they were forwarded to our office for production. Again, the content of the notes was not otherwise altered.

There are multiple reasons to believe this is false. For example, when DOJ submitted notes that Jim Crowell took, they added a date in a redaction, something that could in no way be inadvertent. And as noted, the January 5 notes had already been submitted, without the date change (though then, too, DOJ claimed not to know the date of the document).

But the most important tell is that, when Ballantine sent Powell the three documents altered to add dates, the protective order footer on the documents had been removed in all three, in the case of McCabe’s notes, actually redacted. When she released the re-altered documents (someone digitally removed the date in the McCabe notes rather than providing a new scan), the footer had been added back in. This can easily be seen by comparing the altered documents with the re-altered documents.

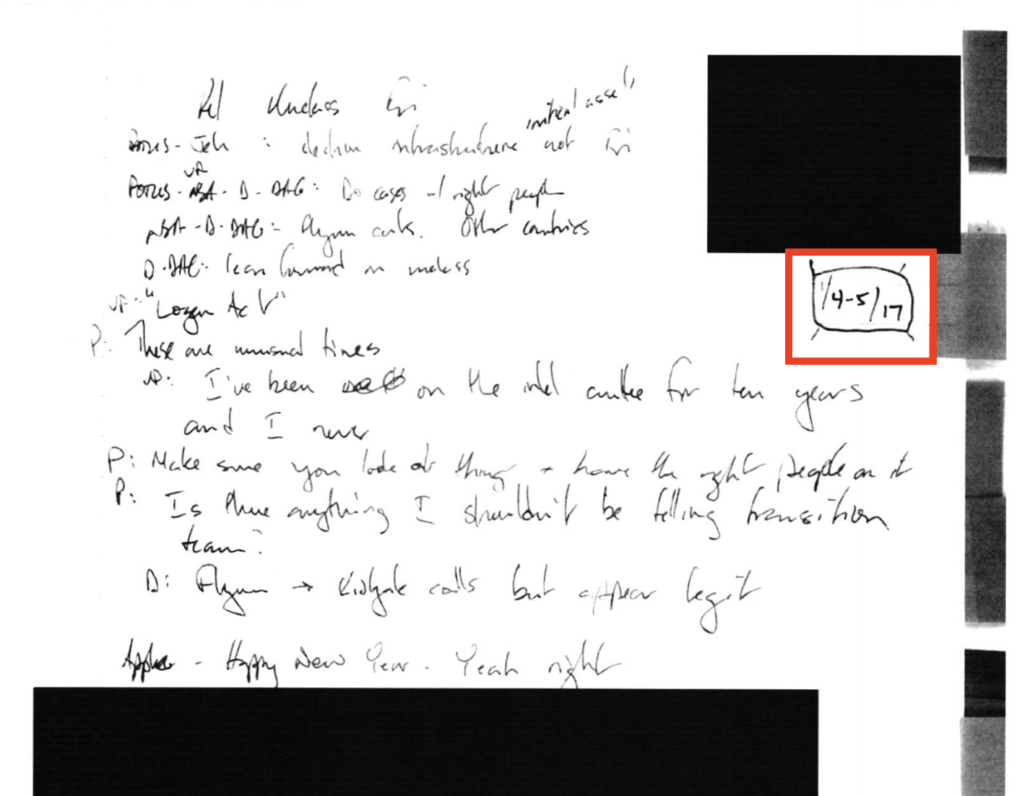

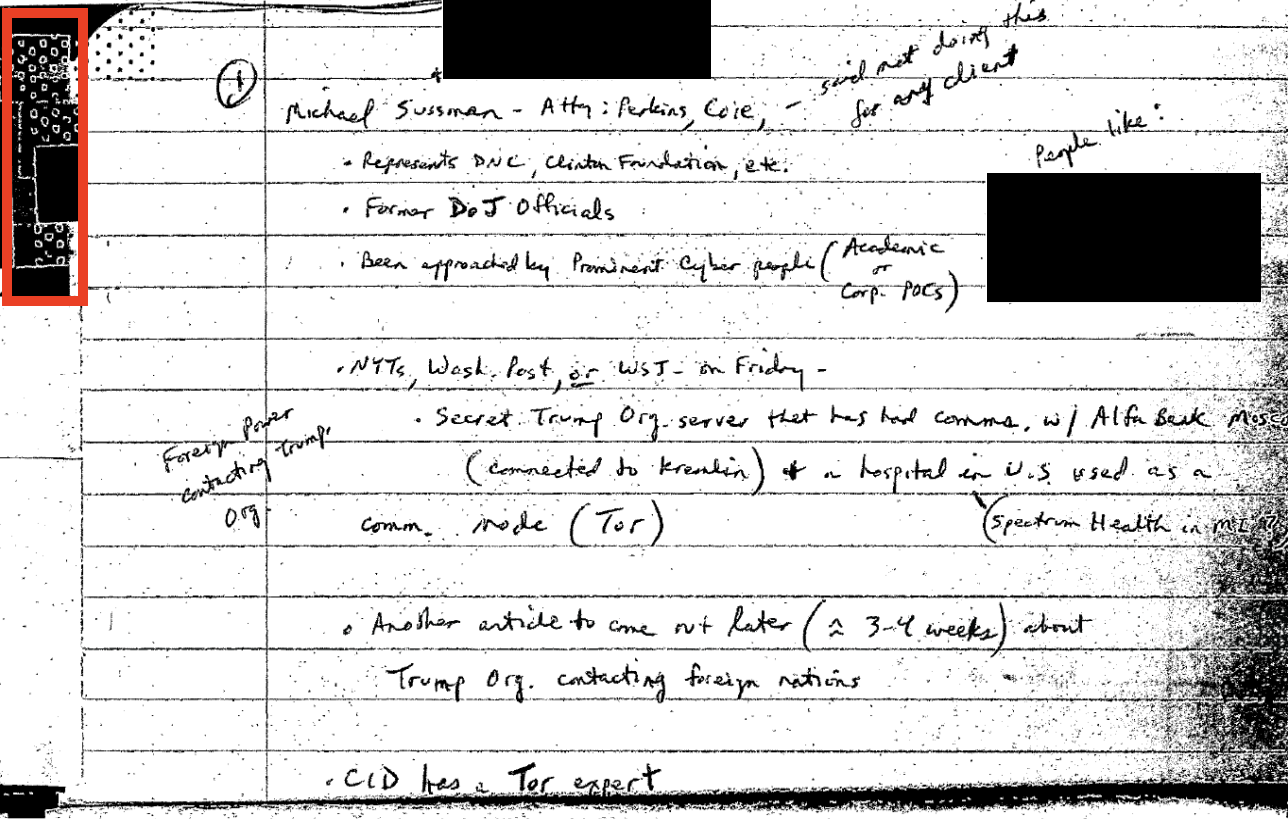

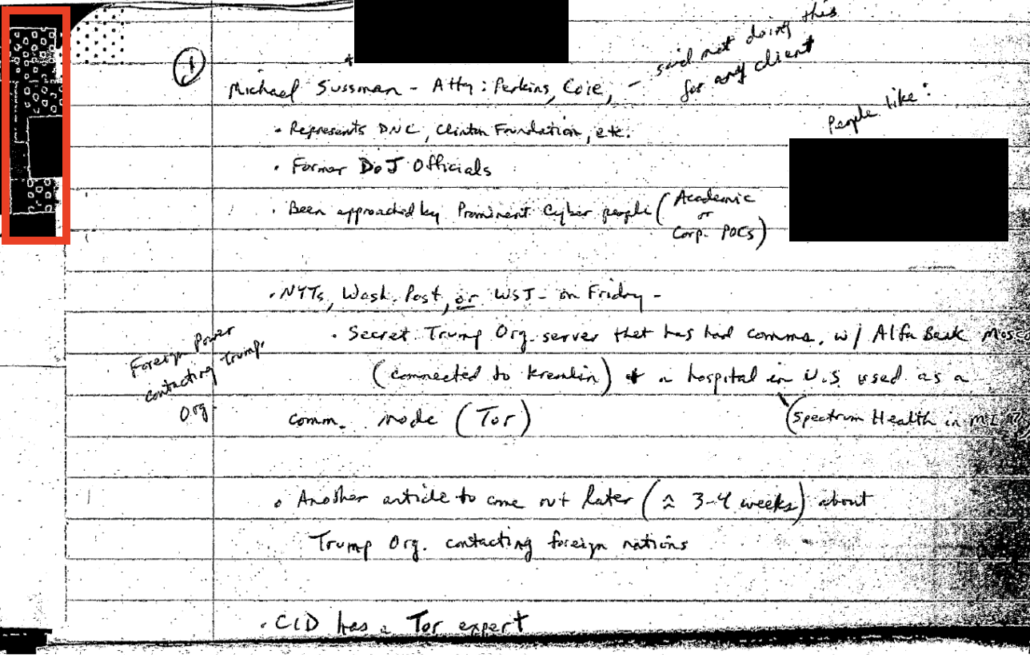

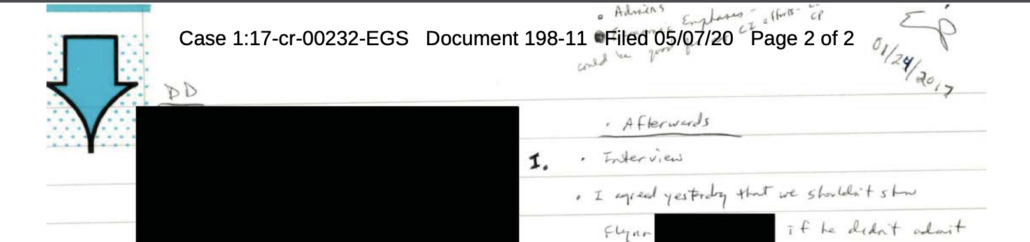

The altered January 5, 2017 Strzok notes, without the footer:

The realtered January 5, 2017 Strzok notes, with the footer:

The second set of Strzok notes (originally altered to read March 28), without the footer:

The second set of Strzok notes, with the footer.

The altered McCabe notes, with the footer redacted out:

The realtered McCabe notes, with the footer unredacted:

This is something that had to have happened at DOJ (see William Ockham’s comments below and this post for proof in the metadata that these changes had to have been done by Ballantine). The redaction of the footers strongly suggests that they were provided to Powell with the intention of facilitating their further circulation (the other two documents she shared with Powell that day had no protective order footer). In addition, each of these documents should have a new Bates stamp.

DOJ redacted Brandon Van Grack’s non-misconduct

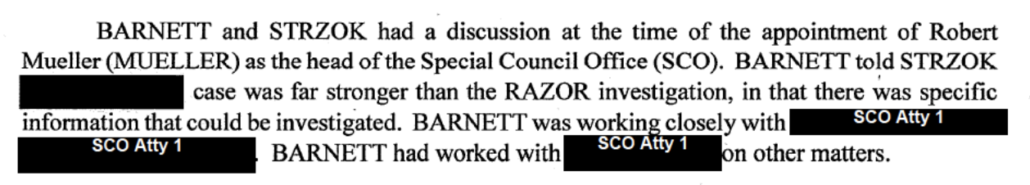

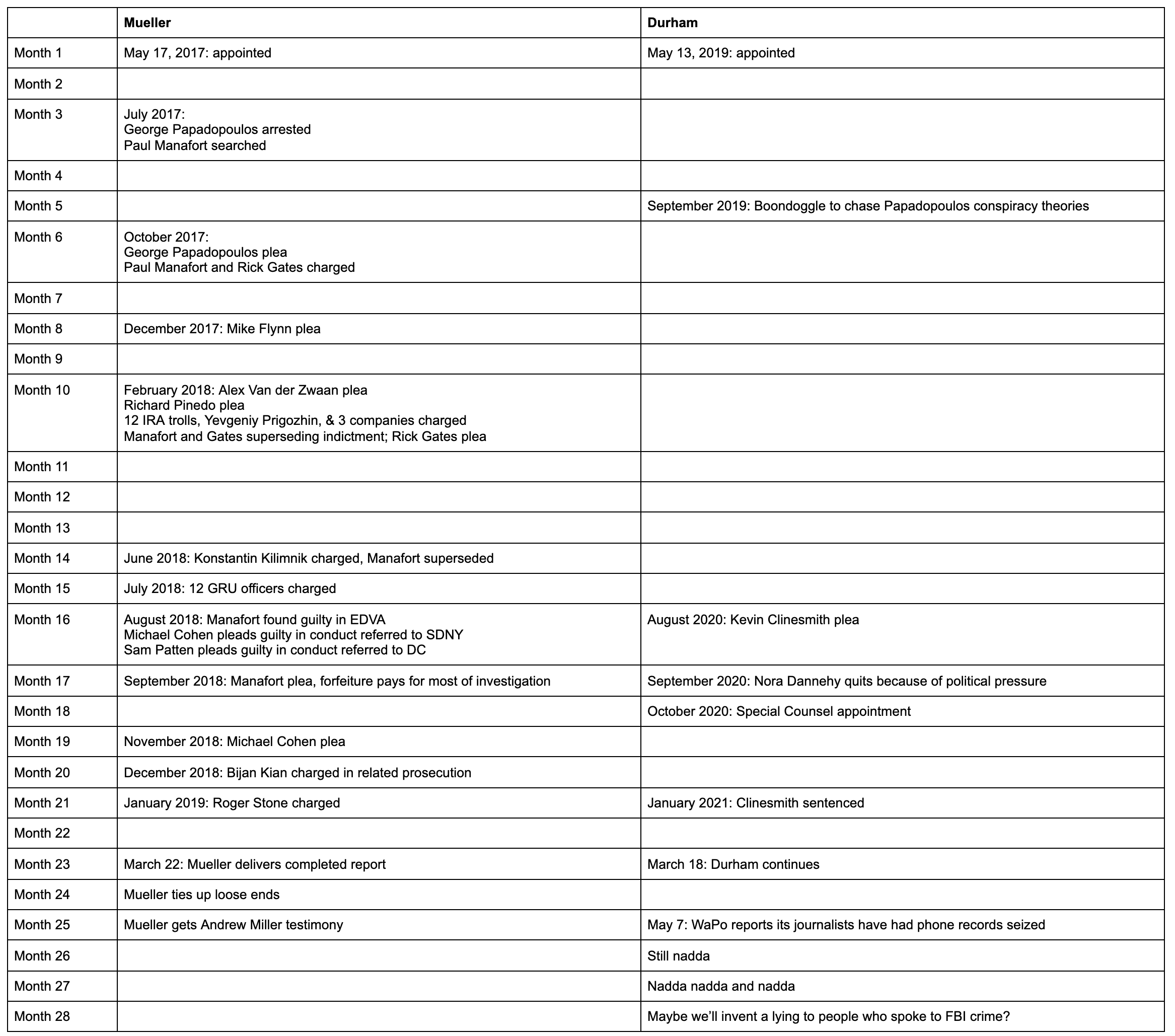

On September 24, DOJ submitted a report of an FBI interview Jeffrey Jensen’s team did with an Agent who sent pro-Trump texts on his FBI-issued phone, Bill Barnett. In the interview, Barnett made claims that conflicted with actions he had taken on the case. He claimed to be unaware of evidence central to the case against Flynn (for example, that Flynn told Sergey Kislyak that Trump knew of something said on one of their calls). He seemed unaware of the difference between a counterintelligence investigation and a criminal one. And he made claims about Mueller prosecutors — Jeannie Rhee and Andrew Weissmann — with whom he didn’t work directly. In short, the interview was obviously designed to tell a politically convenient story, not the truth.

Even worse than the politicized claims that Barnett made, the FBI or DOJ redacted the interview report such that all reference to Brandon Van Grack was redacted, substituting instead with the label, “SCO Atty 1.” (References to Jeannie Rhee, Andrew Weissmann, and Andrew Goldstein were not redacted; there are probable references to Adam Jed and Zainab Ahmad that are not labeled at all.)

The result of redacting Van Grack’s name is that it hid from Judge Sullivan many complimentary things that Barnett had to say about Van Grack:

Van Grack’s conduct was central to DOJ’s excuse for throwing out the Flynn prosecution. Powell repeatedly accused Van Grack, by name, of engaging in gross prosecutorial misconduct. Yet the report was submitted to Judge Sullivan in such a way as to hide that Barnett had no apparent complaints about Van Grack’s actions on the Flynn case.

I have no reason to believe that Ballantine made those redactions. But according to the discovery letter she sent to Powell, she sent an unredacted copy to Flynn’s team, while acknowledging that the one she was submitting to the docket was redacted. Thus, she had to have known she was hiding material information from the Court when she submitted the interview report.

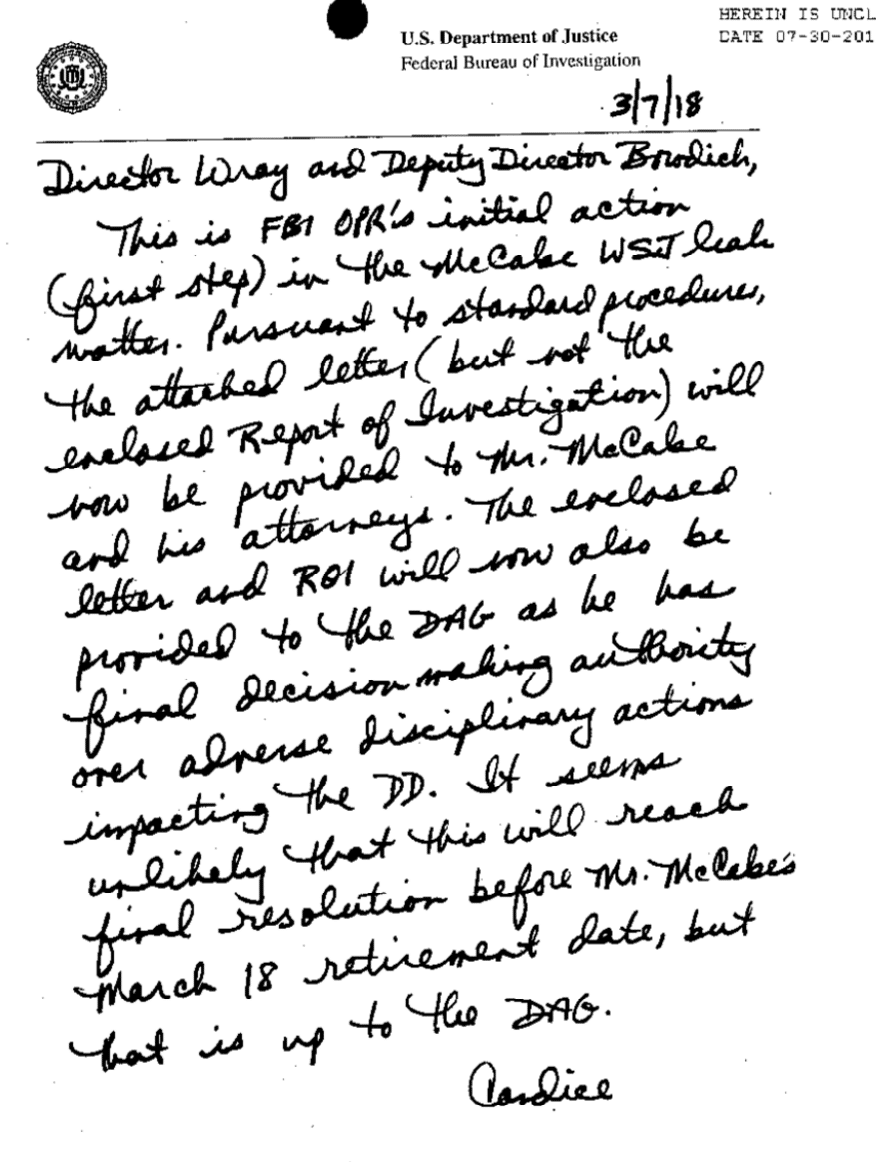

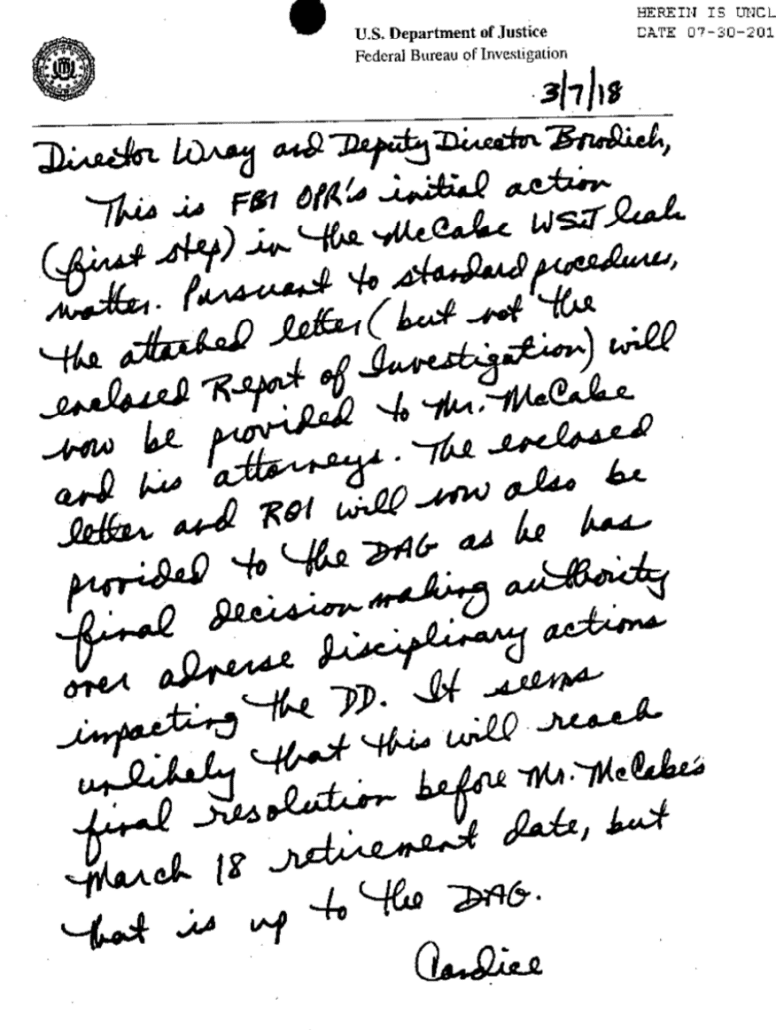

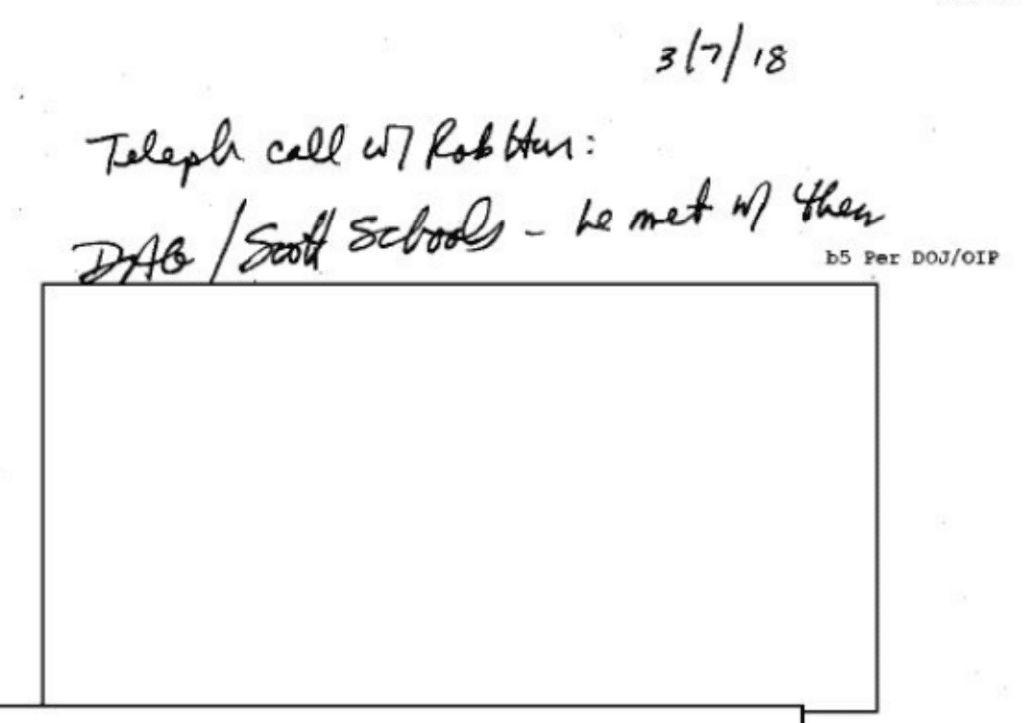

Ballantine falsely claimed Strzok and McCabe validated their notes

After some of these alterations were made public, Judge Sullivan ordered DOJ to authenticate all the documents they had submitted as part of their effort to overturn the Flynn prosecution. The filing submitted in response was a masterpiece of obfuscation, with three different people making claims while dodging full authentication for some of the most problematic documents. In the filing that Ballantine submitted, she claimed that Michael Bromwich and Aitan Goelman, lawyers for McCabe and Strzok, “confirmed” that no content was altered in the notes.

The government acknowledges its obligation to produce true and accurate copies of documents. The government has fully admitted its administrative error with respect to the failure to remove three reviewer sticky notes containing estimated date notations affixed to three pages of undated notes (two belonging to former Deputy Assistant Director Peter Strzok, and one page belonging to former Deputy Director Andrew McCabe) prior to their disclosure. These dates were derived from surrounding pages’ dates in order to aid secondary reviewers. These three sticky notes were inadvertently not removed when the relevant documents were scanned by the FBI for production in discovery. See ECF 259. The government reiterates, however, that the content of those exhibits was not altered in any way, as confirmed by attorneys for both former FBI employees. [underline original]

According to an email Bromwich sent Ballantine, when Ballantine asked for help validating the transcripts DOJ did of McCabe’s notes, McCabe declined to do so.

I have spoken with Mr. McCabe and he declines to provide you with any information in response to your request.

He believes DOJ’s conduct in this case is a shocking betrayal of the traditions of the Department of the Justice and undermines the rule of law that he spent his career defending and upholding. If you share with the Court our decision not to provide you with assistance, we ask that you share the reason.

We would of course respond to any request that comes directly from the Court.

And according to an email Goelman sent to Ballantine, they said they could not check transcriptions without the original copies of documents.

Sorry not to get back to you until now. We have looked at the attachments to the email you sent yesterday (Sunday) afternoon. We are unable to certify the authenticity of all of the attachments or the accuracy of the transcriptions. To do so, we would need both more time and access to the original notes, particularly given that U.S. Attorney Jensen’s team has already been caught altering Pete’s notes in two instances. However, we do want to call your attention to the fact that Exhibit 198-11 is mislabeled, and that these notes are not the notes of Pete “and another agent” taken during the Flynn interview.

Additionally, we want to register our objection to AUSA Ken Kohl’s material misstatements to Judge Sullivan during the September 29, 2020, 2020, [sic] telephonic hearing, during which Mr. Kohl inaccurately represented that Pete viewed himself as an “insurance policy” against President Trump’s election.

I have no reason to believe the content was altered, though I suspect other things were done to McCabe’s notes to misrepresent the context of a reference in his notes to Flynn. But not only had McCabe and Strzok not validated their notes, but they had both pointedly refused to. Indeed, during this same time period, DOJ was refusing to let McCabe see his own notes to prepare for testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Nevertheless, Ballantine represented to Judge Sullivan that they had.

It baffles me why DOJ would put Ballantine on the most important January 6 case. Among other things, the conduct I’ve laid out here will make it easy for the defendants to accuse DOJ of similar misconduct on the Proud Boys case — and doing just that happens to be Nordean’s primary defense strategy.

But I’m mindful that there are people in DC’s US Attorney’s Office (not Ballantine) who took actions in the past that may have made the January 6 attack more likely. In a sentencing memo done on Barr’s orders, prosecutors attempting to minimize the potential sentence against Roger Stone suggested that a threat four Proud Boys helped Roger Stone make against Amy Berman Jackson was no big deal, unworthy of a sentencing enhancement.

Second, the two-level enhancement for obstruction of justice (§ 3C1.1) overlaps to a degree with the offense conduct in this case. Moreover, it is unclear to what extent the defendant’s obstructive conduct actually prejudiced the government at trial.

Judge Jackson disagreed with this assessment. In applying the enhancement, she presciently described how dangerous Stone and the Proud Boys could be if they incited others.

Here, the defendant willfully engaged in behavior that a rational person would find to be inherently obstructive. It’s important to note that he didn’t just fire off a few intemperate emails. He used the tools of social media to achieve the broadest dissemination possible. It wasn’t accidental. He had a staff that helped him do it.

As the defendant emphasized in emails introduced into evidence in this case, using the new social media is his “sweet spot.” It’s his area of expertise. And even the letters submitted on his behalf by his friends emphasized that incendiary activity is precisely what he is specifically known for. He knew exactly what he was doing. And by choosing Instagram and Twitter as his platforms, he understood that he was multiplying the number of people who would hear his message.

By deliberately stoking public opinion against prosecution and the Court in this matter, he willfully increased the risk that someone else, with even poorer judgment than he has, would act on his behalf. This is intolerable to the administration of justice, and the Court cannot sit idly by, shrug its shoulder and say: Oh, that’s just Roger being Roger, or it wouldn’t have grounds to act the next time someone tries it.

The behavior was designed to disrupt and divert the proceedings, and the impact was compounded by the defendant’s disingenuousness.

The people at DOJ who claimed that this toxic team was not dangerous in the past may want to downplay the critical role that Stone and the Proud Boys played — using the same kind of incendiary behavior — in the January 6 assault.

Whatever the reason, though, it is inexcusable that DOJ would put someone like Ballantine on this case. Given Ballantine’s past actions, it risks sabotaging the entire January 6 investigation.

DOJ quite literally put someone who, less than a year ago, facilitated Sidney Powell’s lies onto a prosecution team investigating the aftermath of further Sidney Powell lies.

Update: DC USAO’s media person refused to clarify what Ballantine’s role is, even though it was publicly acknowledged in court.

We are not commenting on cases beyond what is stated or submitted to the Court. We have no comment in response to your question.

Update: Added links to William Ockham’s proof that Ballantine made the realteration of the McCabe notes.

Update: One more point on this. I am not claiming here that anyone at DOJ is deliberately trying to sabotage the January 6 investigation, just that putting someone who, less than a year ago, made multiple representations to a judge that could call into question her candor going forward could discredit the Proud Boys investigation. I think it possible that supervisors at DC USAO put her on the team because they urgently need resources and she was available (possibly newly so after the end of her TDY). I think it possible that supervisors at DC USAO who are also implicated in Barr’s politicization, perhaps more closely tied to the intervention in the Stone case, put her there with corrupt intent.

But it’s also important to understand that up until February 2020, she was viewed as a diligent, ruthless prosecutor. I presume she buckled under a great deal of pressure after that and found herself in a place where competing demands — her duty of candor to the Court and orders from superiors all the way up to the Attorney General — became increasingly impossible to square.

Importantly, Lisa Monaco’s chief deputy John Carlin, and probably Monaco herself, would know Ballantine from their past tenure in the National Security Division as that heretofore ruthless national security prosecutor. The only mainstream outlet that covered anything other than DOJ’s admission they had added post-its to the notes was Politico. And the instinct not to punish career employees like Ballantine would mean what she would have avoided any scrutiny with the transition. So her assignment to the case is not itself evidence of an attempt to sabotage the prosecution.