It’s Not So Much that Manafort Lied and Lied and Lied, It’s that His Truth Evolved

Paul Manafort submitted his filing arguing that he didn’t intentionally lie when he lied repeatedly to Mueller last fall. The structure of the filing largely tracks that of Mueller’s submission last week, though it appears to have a more substantive introduction to his discussions of a peace deal with Konstantin Kilimnik, resulting this organization:

- Payment to/from Rebuilding America Now (0-series exhibits)

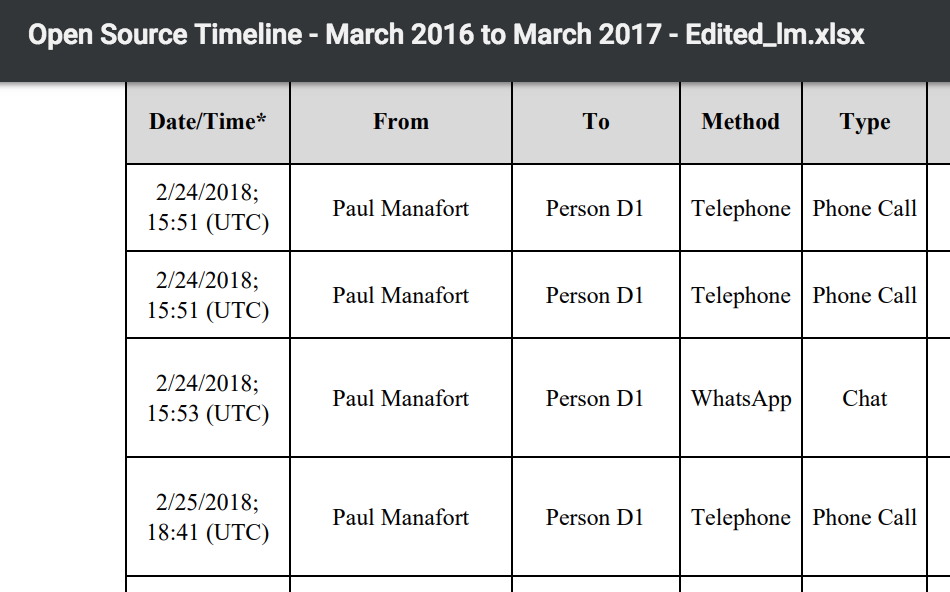

- Konstantin Kilimnik’s role in witness tampering (100-series exhibits)

- Interactions with Kilimnik (200-series exhibits)

a) Discussions of the Ukraine Peace Deal

b) One meeting

c) Another meeting

d) A 2018 proposal

e) Manafort’s false statements (almost certainly about sharing polling data)

- Another DOJ investigation (possibly that of Steve Calk) (300-series exhibits)

- Manafort’s contact with the Administration (400-series exhibits)

Did Manafort change excuses for forgetting about a Ukrainian peace deal?

This filing is heavily redacted, so it’d be rash to make conclusions based on what little we can see. But it seems possible Manafort is offering a slightly different excuse for forgetting some discussions about Ukrainian peace deals than he earlier offered.

In his redaction fail filing, Manafort claimed he forgot about his discussions with Kilimnik about peace because he was so busy running Trump’s campaign.

In fact, during a proffer meeting held with the Special Counsel on September 11, 2018, Mr. Manafort explained to the Government attorneys and investigators that he would have given the Ukrainian peace plan more thought, had the issue not been raised during the period he was engaged with work related to the presidential campaign. Issues and communications related to Ukrainian political events simply were not at the forefront of Mr. Manafort’s mind during the period at issue and it is not surprising at all that Mr. Manafort was unable to recall specific details prior to having his recollection refreshed. The same is true with regard to the Government’s allegation that Mr. Manafort lied about sharing polling data with Mr. Kilimnik related to the 2016 presidential campaign. (See Doc. 460 at 6).

I’ve observed that that’s a pretty shitty excuse for forgetting a Madrid meeting in 2017 and writing a report on a Ukraine plan in 2018.

But in this filing, Manafort seems to be arguing that he forgot about one discussion of a peace plan because he did not consider it viable, but he considered a different one viable.

During the interview, there was continual confusion when discussing [redacted] because Mr. Manafort differentiated between the [redacted] discussed at the [redacted], which Mr. Manafort did not feel would work and did not support, and [redacted]. While Mr. Manafort did not initially recall Mr. Kilimnik’s follow up contact about [redacted], after his recollection was refreshed by showing him email, he readily acknowledged that he had seen the email at the time.5

That still doesn’t seem to explain his 2018 peace plan — which he after all wrote a proposal for.

In any case, he seems to have significantly changed his excuse as the number of times he discussed Ukrainian peace plans proliferated well beyond the campaign.

Could Rick Gates make a showing?

In response to an ABJ order the government submitted a filing stating that it couldn’t say whether it would provide witness testimony Friday until after it saw Manafort’s filing.

The question of whether live testimony will be necessary to resolve any factual issue will depend on the defendant’s upcoming submission. The defense has not submitted any evidence to date. If it does not, the Court can resolve the factual issues based on the evidence submitted, drawing inferences regarding intent from that evidence, with the benefit of the parties’ arguments at the conference scheduled for January 25th. If there are material factual disputes, however, witness testimony will assist in the resolution of those issues. Finally, the government is of course prepared to proceed with witness testimony if the Court believes it will assist in resolution of the matter.

At the time, I imagined they were thinking only of the FBI Agent who submitted the declaration in the case.

But Manafort twice either reinterprets or disputes Gates’ testimony, once on whether Manafort told the truth about sharing polling data with Kilimnik.

And once (even more heavily redacted) on whether Manafort had ongoing contacts with the Administration (in an earlier filing, Manafort had claimed Mueller was relying on hearsay regarding one of its claims). So it’s possible that’s the witness the government had in mind.

That said, in the language in Manafort’s filing addressing whether addition evidence is needed, he said no additional evidence was needed.

Manafort believes that the information the Court has received, including pleadings and various exhibits, provide a sufficient factual record to allow the Court to decide the issues presented without the need for additional evidence.

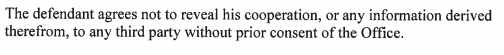

Paulie still hiding the campaign finance violations

As I’ve noted before, the reason Manafort’s lies about getting a loan or whatever via Rebuilding America Now matter is that whatever the scheme entailed, it likely would have amounted to a campaign finance violation because he, the campaign manager, would have been coordinating (indeed, seemingly getting paid by!) a SuperPAC. It’s fairly clear he kept changing his story about this (though it remains clear, now, that the payment served to pay his legal fees). Ultimately, though, Manafort effectively says no-harm-no-foul because he paid taxes on the payment.

As Mr. Manafort clarified to the OSC, there was no agreement about the terms of the payment of Mr. Manafort’s legal fees. This resulted in confusion as to whether the funds amounted to a loan, income, or even a gift. In an abundance of caution, Mr. Manafort ultimately reported the amount as income on his tax returns.

[snip]

Finally, the OSC claims that Mr. Manafort lied when he discussed that the payment might have been a loan. (Doc. 474 at 4, ¶7). This discussion was aimed at explaining the loan agreement, which Mr. Manafort had not remembered previously, and his continuing confusion about how the money was being treated by the payor. The uncertainty of the terms of the payment were verified by Mr. Manafort’s civil attorney and accountant.

Importantly, it should be noted that Mr. Manafort reported the payment on his own tax return as income. See Gov. Ex. 15. Further, Mr. Manafort identified that the payment came from [redacted]. Id. At bottom, then, there was no attempt to conceal the payment or the source on the income tax return that he filed with the government, and he ultimately chose to report the payment as income—the most tax disadvantageous manner in which it could have been handled.

But that entirely dodges the reason why Manafort would have wanted to obscure the relationship here in the first place, which is that if he admits it was all thought out ahead of time then the Trump campaign is exposed legally.

ABJ insists on Manafort’s presence

Having read all these filings, in unredacted form, ABJ did set a hearing for Friday morning, as she said she might do. Manafort’s lawyers asked — as they have in past hearings — for Manafort to be excused (remember, it’s a pain in the ass to get transported from the jail). But ABJ refused this request, noting,

Given the number of court appearances defendant has been permitted to waive, the significance of the issues at stake, and the fact that his being available to consult with counsel may reduce the likelihood that the defense position with respect to the issues discussed will change after the hearing, defendant’s motion is denied without prejudice to future motions.

His lawyers are now asking for permission for him to wear a suit.

It’s hard to read what she means with the minute order — aside from wanting to resolve this issue at the hearing. She clearly isn’t treating the government’s claims as a slam dunk (nor should she, considering the grave consequences for Manafort).

As I disclosed last July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.