“Stand Back and Stand By:” John Pierce’s Plan for a Public Authority or — More Likely — a MyPillow Defense

In a Friday hearing in the omnibus Oath Keeper conspiracy case, John Pierce — who only just filed an appearance for Kenneth Harrelson in that case — warned that he’s going to mount a very vigorous public authority defense. He claimed that such a defense would require reviewing all video.

Pierce is a Harvard-trained civil litigator involved in the more conspiratorial side of Trumpist politics. Last year he filed a lawsuit for Carter Page that didn’t understand who (Rod Rosenstein, among others) needed to be included to make the suit hold up, much less very basic things about FISA. As someone who’d like to see the unprecedented example of Page amount to something, I find that lawsuit a horrible missed opportunity.

John Pierce got fired by Kyle Rittenhouse

Of late, he has made news for a number of controversial steps purportedly in defense of accused Kenosha killer Kyle Rittenhouse. A recent New Yorker article on Rittenhouse’s case, for example, described that Pierce got the Rittenhouses to agree to a wildly inflated hourly rate and sat on donations in support of Rittenhouse’s bail for a month after those funds had been raised. Then, when Kyle’s mother Wendy tried to get Pierce to turn over money raised for their living expenses, he instead claimed they owed him.

Pierce met with the Rittenhouses on the night of August 27th. Pierce Bainbridge drew up an agreement calling for a retainer of a hundred thousand dollars and an hourly billing rate of twelve hundred and seventy-five dollars—more than twice the average partner billing rate at top U.S. firms. Pierce would be paid through #FightBack, which, soliciting donations through its Web site, called the charges against Rittenhouse “a reactionary rush to appease the divisive, destructive forces currently roiling this country.”

Wisconsin’s ethics laws restrict pretrial publicity, but Pierce began making media appearances on Rittenhouse’s behalf. He called Kenosha a “war zone” and claimed that a “mob” had been “relentlessly hunting him as prey.” He explicitly associated Rittenhouse with the militia movement, tweeting, “The unorganized ‘militia of the United States consists of all able-bodied males at least seventeen years of age,’ ” and “Kyle was a Minuteman protecting his community when the government would not.”

[snip]

In mid-November, Wood reported that Mike Lindell, the C.E.O. of MyPillow, had “committed $50K to Kyle Rittenhouse Defense Fund.” Lindell says that he thought his donation was going toward fighting “election fraud.” The actor Ricky Schroder contributed a hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Pierce finally paid Rittenhouse’s bail, with a check from Pierce Bainbridge, on November 20th—well over a month after #FightBack’s Web site indicated that the foundation had the necessary funds.

[snip]

Wendy said of the Rittenhouses’ decision to break with Pierce, “Kyle was John’s ticket out of debt.” She was pressing Pierce to return forty thousand dollars in donated living expenses that she believed belonged to the family, and told me that Pierce had refused: “He said we owed him millions—he ‘freed Kyle.’ ”

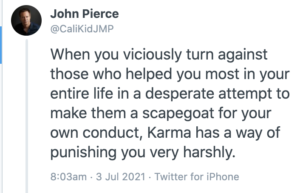

Possibly in response to the New Yorker piece, Pierce has been tweeting what might be veiled threats to breach attorney-client privilege.

Pierce assembles a collection of characters for his screen play

Even as that has been going on, however, Pierce has been convincing one after another January 6 defendant to let him represent them. The following list is organized by the date — in bold — when Pierce first filed an appearance for that defendant (I’ll probably update this list as Pierce adds more defendants):

1. Christopher Worrell: Christopher Worrell is a Proud Boy from Florida arrested on March 12. Worrell traveled to DC for the December MAGA protest, where he engaged in confrontational behavior targeting a journalist. He and his girlfriend traveled to DC for January 6 in vans full of Proud Boys paid for by someone else. He was filmed spraying pepper spray at cops during a key confrontation before the police line broke down and the initial assault surged past. Worrell was originally charged for obstruction and trespassing, but later indicted for assault and civil disorder and trespassing (dropping the obstruction charge). He was deemed a danger, in part, because of a 2009 arrest for impersonating a cop involving “intimidating conduct towards a total stranger in service of taking the law into his own hands.” Pierce first attempted to file a notice of appearance on March 18. Robert Jenkins (along with John Kelly, from Pierce’s firm) is co-counsel on the case. Since Pierce joined the team, he has indulged Worrell’s claims that he should not be punished for assaulting a cop, but neither that indulgence nor a focus on Worrell’s non-Hodgkins lymphoma nor an appeal succeeded at winning his client release from pre-trial detention.

2. William Pepe: William Pepe is a Proud Boy charged in a conspiracy with Dominic Pezzola and Matthew Greene for breaching the initial lines of defense and, ultimately, the first broken window of the Capitol. Pepe was originally arrested on January 11, though is out on bail. Pierce joined Robert Jenkins on William Pepe’s defense team on March 25. By April, Pierce was planning on filing some non-frivolous motions (to sever his case from Pezzola, to move it out of DC, and to dismiss the obstruction count).

3. Paul Rae: Rae is another of Pierce’s Proud Boy defendants and his initial complaint suggested Rae could have been (and could still be) added to the conspiracy indictments against the Proud Boys already charged. He was indicted along with Arthur Jackman for obstruction and trespassing; both tailed Joe Biggs on January 6, entering the building from the East side after the initial breach. Pierce filed to join Robert Jenkins in defending Rae on March 30.

4. Stephanie Baez: On June 9, Pierce filed his appearance for Stephanie Baez. Pierce’s interest in Baez’ case makes a lot of sense. Baez, who was arrested on trespassing charges on June 4, seems to have treated the January 6 insurrection as an opportunity to shop for her own Proud Boy boyfriend. Plus, she’s attractive, unrepentant, and willing to claim there was no violence on January 6. Baez has not yet been formally charged (though that should happen any day).

5. Victoria White: If I were prosecutors, I’d be taking a closer look at White to try to figure out why John Pierce decided to represent her (if it’s not already clear to them; given the timing, it may simply be because he believed he needed a few women defendants to tell the story he wants to tell). White was detained briefly on January 6 then released, and then arrested on April 8 on civil disorder and trespassing charges. At one point on January 6, she was filmed trying to dissuade other rioters from breaking windows, but then she was filmed close to and then in the Tunnel cheering on some of the worst assault. Pierce filed his notice of appearance in White’s case on June 10.

Ryan Samsel: After consulting with Joe Biggs, Ryan Samsel kicked off the riot by approaching the first barriers and — with several other defendants — knocking over a female cop, giving her a concussion. He was arrested on January 30 and is still being held on his original complaint charging him with assault and civil disorder. He’s obviously a key piece to the investigation and for some time it appeared the government might have been trying to persuade him that the way to minimize his significant exposure (he has an extensive criminal record) would be to cooperate against people like Biggs. But then he was brutally assaulted in jail. Detainees have claimed a guard did it, and given that Samsel injured a cop, that wouldn’t be unheard of. But Samsel seemed to say in a recent hearing that the FBI had concluded it was another detainee. In any case, the assault set off a feeding frenzy among trial attorneys seeking to get a piece of what they imagine will be a huge lawsuit against BOP (as it should be if a guard really did assault him). Samsel is now focused on getting medical care for eye and arm injuries arising from the assault. And if a guard did do this, then it would be a key part of any story Pierce wanted to tell. After that feeding frenzy passed, Pierce filed an appearance on June 14, with Magistrate Judge Zia Faruqui releasing his prior counsel on June 25. Samsel is a perfect defendant for Pierce, though (like Rittenhouse), the man badly needs a serious defense attorney. Update: On July 27, Samsel informed Magistrate Judge Zia Faruqui that he would be retaining new counsel.

6. James McGrew: McGrew was arrested on May 28 for assault, civil disorder, obstruction, and trespassing, largely for some fighting with cops inside the Rotunda. His arrest documents show no ties to militias, though his arrest affidavit did reference a 2012 booking photo. Pierce filed his appearance to represent McGrew on June 16.

Alan Hostetter: John Pierce filed as Hostetter’s attorney on June 24, not long after Hostetter was indicted with five other Three Percenters in a conspiracy indictment paralleling those charging the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys. Hostetter was also active in Southern California’s anti-mask activist community, a key network of January 6 participants. Hostetter and his defendants spoke more explicitly about bringing arms to the riot, and his co-defendant Russell Taylor spoke at the January 5 rally. On August 3, Hostetter replaced Pierce.

7, 8, 9. On June 30, Pierce filed to represent David Lesperance, and James and Casey Cusick. As I laid out here, the FBI arrested the Cusicks, a father and son that run a church, largely via information obtained from Lesperance, their parishioner. They are separately charged (Lesperance, James Cusick, Casey Cusick), all with just trespassing. The night before the riot, father and son posed in front of the Trump Hotel with a fourth person besides Lesperance (though Lesperance likely took the photo).

10. Kenneth Harrelson: On July 1, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Harrelson, who was first arrested on March 10. Leading up to January 6, Harrelson played a key role in Oath Keepers’ organizing in Florida, particularly meetings organized on GoToMeeting. On the day of the riot, Kelly Meggs had put him in charge of coordinating with state teams. Harrelson was on the East steps of the Capitol with Jason Dolan during the riot, as if waiting for the door to open and The Stack to arrive; with whom he entered the Capitol. With Meggs, Harrelson moved first towards the Senate, then towards Nancy Pelosi’s office. When the FBI searched his house upon his arrest, they found an AR-15 and a handgun, as well as a go-bag with a semi-automatic handgun and survivalist books, including Ted Kaczynski’s writings. Harrelson attempted to delete a slew of his Signal texts, including a video he sent Meggs showing the breach of the East door. Harrelson had previously been represented by Nina Ginsberg and Jeffrey Zimmerman, who are making quite sure to get removed from Harrelson’s team before Pierce gets too involved.

11. Leo Brent Bozell IV: It was, perhaps, predictable that Pierce would add Bozell to his stable of defendants. “Zeeker” Bozell is the scion of a right wing movement family including his father who has made a killing by attacking the so-called liberal media, and his grandfather, who was a speech writer for Joseph McCarthy. Because Bozell was released on personal recognizance there are details of his actions on January 6 that remain unexplained. But he made it to the Senate chamber, and while there, made efforts to prevent CSPAN cameras from continuing to record the proceedings. He was originally arrested on obstruction and trespassing charges on February 12; his indictment added an abetting the destruction of government property charge, the likes of which have been used to threaten a terrorism enhancement against militia members. Pierce joined Bozell’s defense team (thus far it seems David B. Deitch will remain on the team) on July 6.

12. Nate DeGrave: The night before DeGrave’s quasi co-conspirator Josiah Colt pled guilty, July 13, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Nate DeGrave. DeGrave helped ensure both the East Door and the Senate door remained open.

14. Nathaniel Tuck: On July 19, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Nathaniel Tuck, the Florida former cop Proud Boy.

14. Kevin Tuck: On July 20, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Kevin Tuck, Nathaniel’s father and still an active duty cop when he was charged.

15. Peter Schwartz: On July 26, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Peter Schwartz, the felon out on COVID-release who maced some cops.

16. Jeramiah Caplinger: On July 26, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Jeramiah Caplinger, who drove from Michigan and carried a flag on a tree branch through the Capitol.

Deborah Lee: On August 23, Pierce filed a notice of appearance for Deborah Lee, who was arrested on trespass charges months after her friend Michael Rusyn. On September 2, Lee chose to be represented by public defender Cara Halverson.

17. Shane Jenkins: On August 25, Pierce colleague Ryan Marshall showed up at a status hearing for Jenkins and claimed a notice of appearance for Pierce had been filed the night before. In that same hearing, he revealed that Pierce was in a hospital with COVID, even claiming he was on a ventilator and not responsive. The notice of appearance was filed, using Pierce’s electronic signature, on August 30, just as DOJ started sending out notices that all Pierce cases were on hold awaiting signs of life. Jenkins is a felon accused of bringing a tomahawk to the Capitol and participating in the Lower West Tunnel assaults on cops.

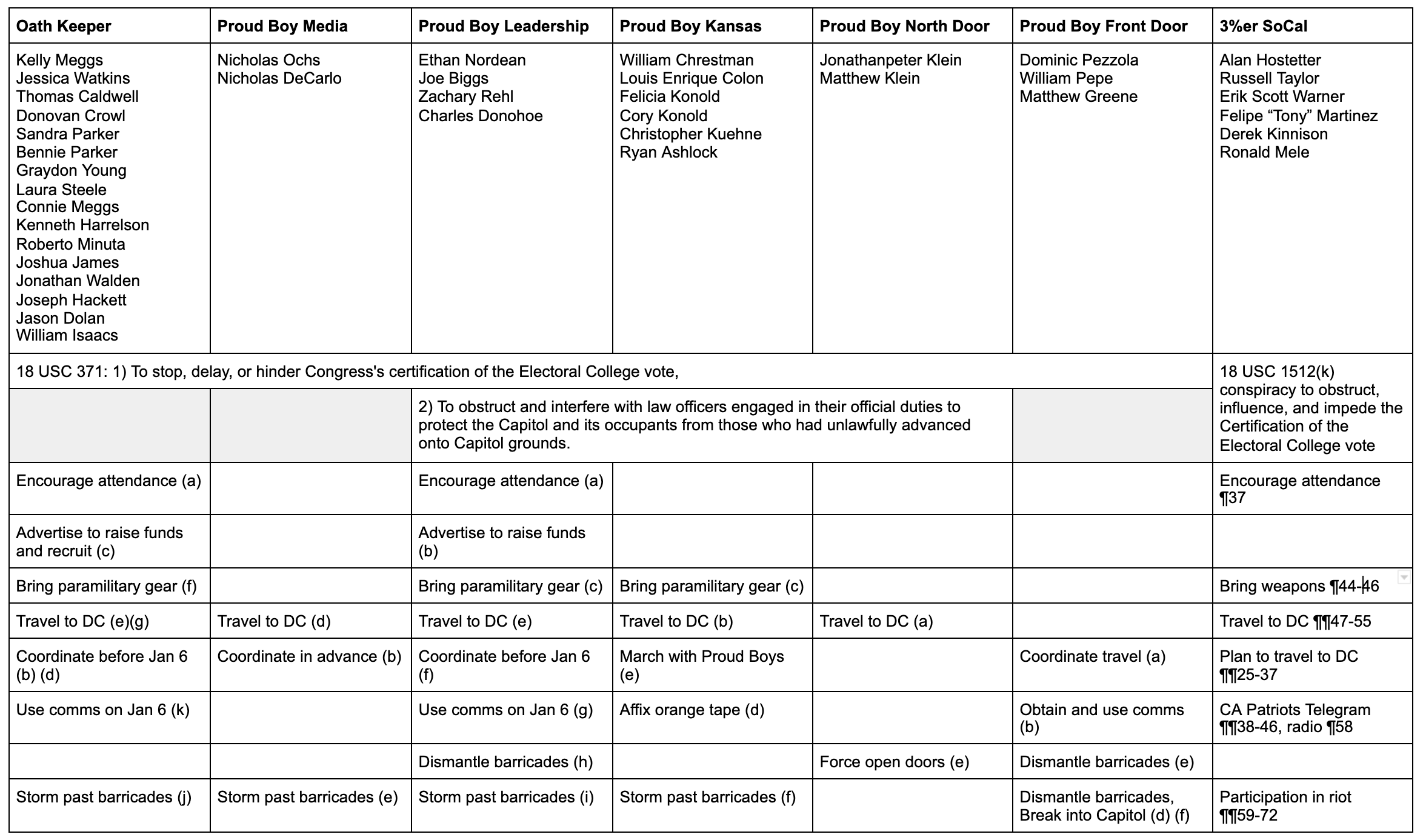

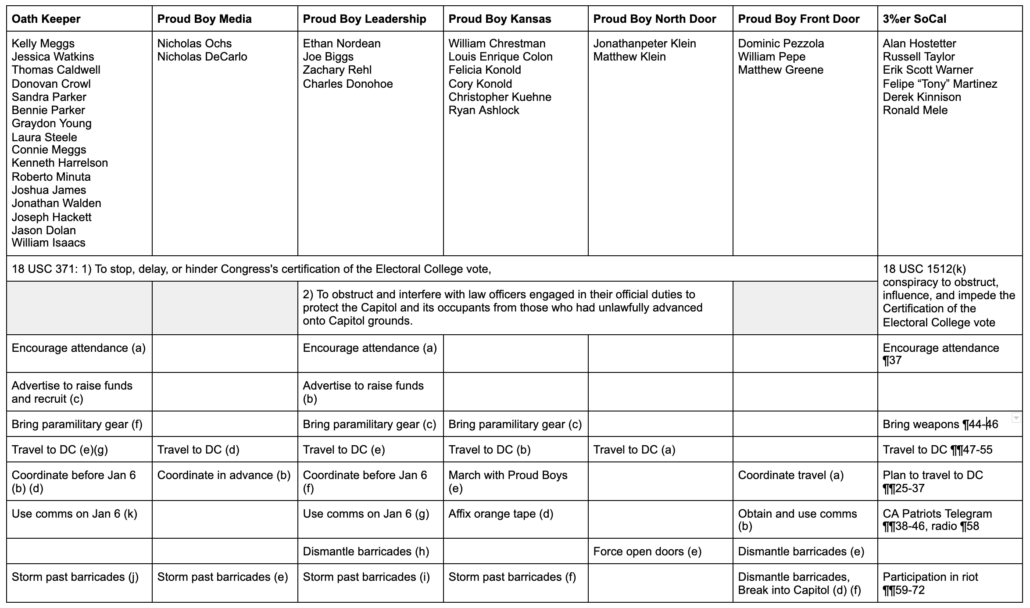

As you can see, Pierce has assembled as cast of defendants as if writing a screenplay, with Proud Boys from key breach points, leading members of the other conspiracies, and other movement conservatives. There are just a few more scenes he would need to fill out to not only be able to write his screenplay, but also to be able to get broad discovery from the government.

This feat is all the more interesting given a detail from the New Yorker article: at one point, Pierce seemed to be claiming to represent Enrique Tarrio and part of his “defense” of Rittenhouse was linking the boy to the Proud Boys.

Six days after the Capitol assault, Rittenhouse and his mother flew with Pierce to Miami for three days. The person who picked them up at the airport was Enrique Tarrio—the Proud Boys leader. Tarrio was Pierce’s purported client, and not long after the shootings in Kenosha he had donated a hundred dollars or so to Rittenhouse’s legal-defense fund. They all went to a Cuban restaurant, for lunch.

Enrique Tarrio would be part of any coordinated Florida-based plan in advance of January 6 and if he wanted to, could well bring down whatever conspiracy there was. More likely, though, he’s attempting to protect any larger conspiracy.

A public authority defense claims the defendant thought they had authority to commit a crime

And with his ties to Tarrio, Pierce claims (to think) he’s going to mount a public authority defense. A public authority defense involves claiming that the defendant had reason to believe he had authority to commit the crimes he did. According to the Justice Manual, there are three possible arguments a defendant might make. The first is that the defendant honestly believed they were authorized to do what they did.

First, the defendant may offer evidence that he/she honestly, albeit mistakenly, believed he/she was performing the crimes charged in the indictment in cooperation with the government. More than an affirmative defense, this is a defense strategy relying on a “mistake of fact” to undermine the government’s proof of criminal intent, the mens rea element of the crime. United States v. Baptista-Rodriguez, 17 F.3d 1354, 1363-68 (11th Cir. 1994); United States v. Anderson, 872 F.2d 1508, 1517-18 & n.4 (11th Cir.), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 1004 (1989); United States v. Juan, 776 F.2d 256, 258 (11th Cir. 1985). The defendant must be allowed to offer evidence that negates his/her criminal intent, id., and, if that evidence is admitted, to a jury instruction on the issue of his/her intent, id., and if that evidence is admitted, he is entitled to a jury instruction on the issue of intent. United States v. Abcasis, 45 F.3d 39, 44 (2d Cir. 1995); United States v. Anderson, 872 F.2d at 1517-1518 & n. In Anderson, the Eleventh Circuit approved the district court’s instruction to the jury that the defendants should be found not guilty if the jury had a reasonable doubt whether the defendants acted in good faith under the sincere belief that their activities were exempt from the law.

There are some defendants among Pierce’s stable for whom this might work. But taken as a whole and individually, most allegedly did things (including obstruction or lying to the FBI) that would seem to evince consciousness of guilt.

The second defense works best (and is invoked most often) for people — such as informants or CIA officers — who are sometimes allowed to commit crimes by the Federal government.

The second type of government authority defense is the affirmative defense of public authority, i.e., that the defendant knowingly committed a criminal act but did so in reasonable reliance upon a grant of authority from a government official to engage in illegal activity. This defense may lie, however, only when the government official in question had actual authority, as opposed to merely apparent authority, to empower the defendant to commit the criminal acts with which he is charged. United States v. Anderson, 872 F.2d at 1513-15; United States v. Rosenthal, 793 F.2d 1214, 1236, modified on other grounds, 801 F.2d 378 (11th Cir. 1986), cert. denied, 480 U.S. 919 (1987). The genesis of the “apparent authority” defense was the decision in United States v. Barker, 546 F. 2d 940 (D.C. Cir. 1976). Barker involved defendants who had been recruited to participate in a national security operation led by Howard Hunt, whom the defendants had known before as a CIA agent but who was then working in the White House. In reversing the defendants’ convictions, the appellate court tried to carve out an exception to the mistake of law rule that would allow exoneration of a defendant who relied on authority that was merely apparent, not real. Due perhaps to the unique intent requirement involved in the charges at issue in the Barker case, the courts have generally not followed its “apparent authority” defense. E.g., United States v. Duggan, 743 F.2d 59, 83-84 (2d Cir. 1984); United States v. Rosenthal, 793 F.2d at 1235-36. If the government official lacked actual or real authority, however, the defendant will be deemed to have made a mistake of law, which generally does not excuse criminal conduct. United States v. Anderson, 872 F.2d at 1515; United States v. Rosenthal, 793 F.2d at 1236; United States v. Duggan, 743 F.2d at 83-84. But see discussion on “entrapment by estoppel,” infra.

Often, spooked up defendants try this as a way to launch a graymail defense, to make such broad requests for classified information to push the government to drop its case. Usually, this effort fails.

I could see someone claiming that Trump really did order the defendants to march on the Capitol and assassinate Mike Pence. Some of the defendants’ co-conspirators (especially Harrelson’s) even suggested they expected Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act. But to make that case would require not extensive review of Capitol video, as Pierce says he wants, but review of Trump’s actions, which would seem to be the opposite of what this crowd might want. Indeed, attempting such a defense might allow prosecutors a way to introduce damning information on Trump that wouldn’t help the defense cause.

The final defense is when a defendant claims that a Federal officer misled them into thinking their crime was sanctioned.

The last of the possible government authority defenses is “entrapment by estoppel,” which is somewhat similar to public authority. In the defense of public authority, it is the defendant whose mistake leads to the commission of the crime; with “entrapment by estoppel,” a government official commits an error and, in reliance thereon, the defendant thereby violates the law. United States v. Burrows, 36 F.3d 875, 882 (9th Cir. 1994); United States v. Hedges, 912 F.2d 1397, 1405 (11th Cir. 1990); United States v. Clegg, 846 F.2d 1221, 1222 (9th Cir. 1988); United States v. Tallmadge, 829 F.2d 767, 773-75 (9th Cir. 1987). Such a defense has been recognized as an exception to the mistake of law rule. In Tallmadge, for example, a Federally licensed gun dealer sold a gun to the defendant after informing him that his circumstances fit into an exception to the prohibition against felons owning firearms. After finding that licensed firearms dealers were Federal agents for gathering and dispensing information on the purchase of firearms, the Court held that a buyer has the right to rely on the representations made by them. Id. at 774. See United States v. Duggan, 743 F.2d at 83 (citations omitted); but, to assert such a defense, the defendant bears the burden of proving that he\she was reasonable in believing that his/her conduct was sanctioned by the government. United States v. Lansing, 424 F.2d 225, 226-27 (9th Cir. 1970). See United States v . Burrows, 36 F.3d at 882 (citing United States v. Lansing, 424 F.2d at 225-27).

This is an extreme form of what defendants have already argued. And in fact, Chief Judge Beryl Howell already addressed this defense in denying Billy Chrestman (a Proud Boy from whose cell Pierce doesn’t yet have a representative) bail. After reviewing the precedents where such a defense had been successful, Howell then explained why it wouldn’t work here. First, because where it has worked, it involved a narrow misstatement of the law that led defendants to unknowingly break the law, whereas here, defendants would have known they were breaking the law because of the efforts from police to prevent their actions. Howell then suggested that a belief that Trump had authorized this behavior would not have been rational. And she concludes by noting that this defense requires that the person leading the defendant to misunderstand the law must have the authority over such law. But Trump doesn’t have the authority, Howell continued, to authorize an assault on the Constitution itself.

Together, this trilogy of cases gives rise to an entrapment by estoppel defense under the Due Process Clause. That defense, however, is far more restricted than the capacious interpretation suggested by defendant, that “[i]f a federal official directs or permits a citizen to perform an act, the federal government cannot punish that act under the Due Process Clause.” Def.’s Mem. at 7. The few courts of appeals decisions to have addressed the reach of this trilogy of cases beyond their facts have distilled the limitations inherent in the facts of Raley, Cox, and PICCO into a fairly restrictive definition of the entrapment by estoppel defense that sets a high bar for defendants seeking to invoke it. Thus, “[t]o win an entrapment-by-estoppel claim, a defendant criminally prosecuted for an offense must prove (1) that a government agent actively misled him about the state of the law defining the offense; (2) that the government agent was responsible for interpreting, administering, or enforcing the law defining the offense; (3) that the defendant actually relied on the agent’s misleading pronouncement in committing the offense; and (4) that the defendant’s reliance was reasonable in light of the identity of the agent, the point of law misrepresented, and the substance of the misrepresentation.” Cox, 906 F.3d at 1191 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

The Court need not dally over the particulars of the defense to observe that, as applied generally to charged offenses arising out of the January 6, 2021 assault on the Capitol, an entrapment by estoppel defense is likely to fail. Central to Raley, Cox, and PICCO is the fact that the government actors in question provided relatively narrow misstatements of the law that bore directly on a defendant’s specific conduct. Each case involved either a misunderstanding of the controlling law or an effort by a government actor to answer to complex or ambiguous legal questions defining the scope of prohibited conduct under a given statute. Though the impact of the misrepresentations in these cases was ultimately to “forgive a breach of the criminal laws,” Cox, 379 U.S. at 588 (Clark, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part), none of the statements made by these actors implicated the potential “waiver of law,” or indeed, any intention to encourage the defendants to circumvent the law, that the Cox majority suggested would fall beyond the reach of the entrapment by estoppel defense, id. at 569. Moreover, in all three cases, the government actors’ statements were made in the specific exercise of the powers lawfully entrusted to them, of examining witnesses at Commission hearings, monitoring the location of demonstrations, and issuing technical regulations under a particular statute, respectively.

In contrast, January 6 defendants asserting the entrapment by estoppel defense could not argue that they were at all uncertain as to whether their conduct ran afoul of the criminal law, given the obvious police barricades, police lines, and police orders restricting entry at the Capitol. Rather, they would contend, as defendant does here, that “[t]he former President gave th[e] permission and privilege to the assembled mob on January 6” to violate the law. Def.’s Mem. at 11. The defense would not be premised, as it was in Raley, Cox, and PICCO, on a defendant’s confusion about the state of the law and a government official’s clarifying, if inaccurate, representations. It would instead rely on the premise that a defendant, though aware that his intended conduct was illegal, acted under the belief President Trump had waived the entire corpus of criminal law as it applied to the mob.

Setting aside the question of whether such a belief was reasonable or rational, as the entrapment by estoppel defense requires, Cox unambiguously forecloses the availability of the defense in cases where a government actor’s statements constitute “a waiver of law” beyond his or her lawful authority. 379 U.S. at 569. Defendant argues that former President Trump’s position on January 6 as “[t]he American head of state” clothed his statements to the mob with authority. Def.’s Mem. at 11. No American President holds the power to sanction unlawful actions because this would make a farce of the rule of law. Just as the Supreme Court made clear in Cox that no Chief of Police could sanction “murder[] or robbery,” 379 U.S. at 569, notwithstanding this position of authority, no President may unilaterally abrogate criminal laws duly enacted by Congress as they apply to a subgroup of his most vehement supporters. Accepting that premise, even for the limited purpose of immunizing defendant and others similarly situated from criminal liability, would require this Court to accept that the President may prospectively shield whomever he pleases from prosecution simply by advising them that their conduct is lawful, in dereliction of his constitutional obligation to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. That proposition is beyond the constitutional pale, and thus beyond the lawful powers of the President.

Even more troubling than the implication that the President can waive statutory law is the suggestion that the President can sanction conduct that strikes at the very heart of the Constitution and thus immunize from criminal liability those who seek to destabilize or even topple the constitutional order. [my emphasis]

In spite of Howell’s warning, we’re bound to see some defense attorneys trying to make this defense anyway. But for various reasons, most of the specific clients that Pierce has collected will have a problem making such claims because of public admissions they’ve already made, specific interactions they had with cops the day of the insurrection, or comments about Trump himself they or their co-conspirators made.

And those problems will grow more acute as the defendants’ co-conspirators continue to enter into cooperation agreements against them.

Or maybe this is a MyPillow defense?

But I’m not sure that Pierce — who, remember, is a civil litigator, not a defense attorney — really intends to mount a public authority defense. His Twitter feed of late suggests he plans, instead, to mount a conspiracy theory defense that the entire thing was a big set-up: the kind of conspiracy theory floated by Tucker Carlson but with the panache of people that Pierce has worked with, like Lin Wood (though even Lin Wood has soured on Pierce).

For example, the other day Pierce asserted that defense attorneys need to see every minute of Capitol Police footage for a week before and after.

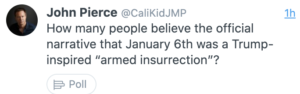

And one of his absurd number of Twitter polls suggests he doesn’t believe that January 6 was a Trump inspired [armed] insurrection.

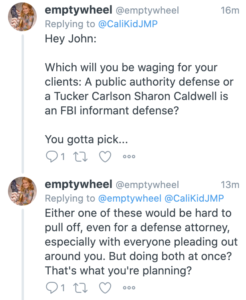

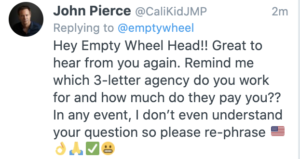

I asked on twitter which he was going to wage, a public authority defense or one based on a claim that this was all informants.

He responded by saying he doesn’t know what the question means.

I asked if he really meant he didn’t know what a public authority defense is, given that he told Judge Mehta he’d be waging one for his clients (or at least Oath Keeper Kenneth Harrelson).

He instead tried to change the subject with an attack on me.

In other words, rather than trying to claim that Trump ordered these people to assault the Capitol, Pierce seems to be suggesting it was all a big attempt to frame Trump and Pierce’s clients.

Don’t get me wrong, a well-planned defense claiming that Trump had authorized all this, one integrating details of what Enrique Tarrio might know about pre-meditation and coordination with Trump and his handlers, might be effective. Certainly, having the kind of broad view into discovery that Pierce is now getting would help. One thing he has done well — with the exception of Lesperance and the Cusicks, if it ever turns into felony charges, as well as Pepe and Samsel, depending on Samsel’s ultimate charges — is pick his clients so as to avoid obvious conflict problems And never forget that there’s a history of right wing terrorists going free based on the kind of screenplays, complete with engaging female characters, that Pierce seems to be planning.

But some of the stuff that Pierce has already done is undermining both of these goals, and the difficulty of juggling actual criminal procedure (as a civil litigator) while trying to write a screenplay could backfire

Pezzola

Pezzola