Jack Smith Takes Up the Aid and Abet Theory Endorsed by Judge Amit Mehta in 2022

Back in February 2022, 32 months ago, think I was the only one who made much of Judge Amit Mehta’s ruling that Trump might plausibly be on the hook for abetting the assaults of cops at the Capitol on January 6.

Halberstam v. Welch remains the high-water mark of the D.C. Circuit’s explanation of aiding-and-abetting liability. The court there articulated two particular principles pertinent to this case. It observed that “the fact of encouragement was enough to create joint liability” under an aiding-and-abetting theory, but “[m]ere presence . . . would not be sufficient.” 705 F.2d at 481. It also said that “[s]uggestive words may also be enough to create joint liability when they plant the seeds of action and are spoken by a person in an apparent position of authority.” Id. at 481–82. A “position of authority” gives a “suggestion extra weight.” Id. at 482.

Applying those principles here, Plaintiffs have plausibly pleaded a common law claim of assault based on an aiding-and-abetting theory of liability. A focus just on the January 6 Rally Speech—without discounting Plaintiffs’ other allegations—gets Plaintiffs there at this stage. President Trump’s January 6 Speech is alleged to have included “suggestive words” that “plant[ed] the seeds of action” and were “spoken by a person in an apparent position of authority.” He was not “merely present.” Additionally, Plaintiffs have plausibly established that had the President not urged rally-goers to march to the Capitol, an assault on the Capitol building would not have occurred, at least not on the scale that it did. That is enough to make out a theory of aiding-and-abetting liability at the pleadings stage.

I noted at the time that Judge Mehta — whose ruling on Trump’s susceptibility to lawsuit for actions taken as a candidate would largely be adopted in the DC Circuit’s opinion on the topic — was presiding over a number of the key assault cases where the since-convicted defendants described being called to DC or ordered to march to the Capitol by Trump before they started beating the shit out of some cops.

He also presided over the Oath Keeper cases.

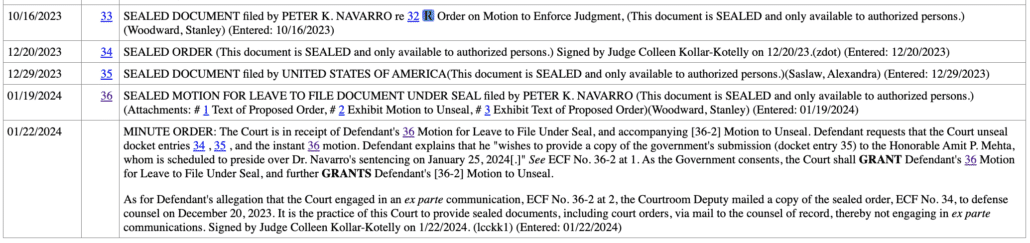

That’s interesting background to Jack Smith’s response to Trump’s supplement to his motion to dismiss his indictment.

As I expected, Smith noted that Trump’s frivolous supplement didn’t even mention the language in the superseding indictment alleging that Trump willfully created false evidence.

Beyond that critical flaw, the defendant’s supplement ignores entirely that the superseding indictment includes allegations that involve the creation of false evidence. As construed by Fischer, Section 1512(c)(1) covers impairment of records, documents, or objects by altering, destroying, mutilating, or concealing them, and Section 1512(c)(2) covers the impairment (or attempted impairment) of records, documents, and objects by other means—such as by “creating false evidence.” 144 S. Ct. at 2185-86 (citing United States v. Reich, 479 F.3d 179 (2d Cir. 2007) (Sotomayor, J.)). In Reich, for example, the defendant was convicted under Section 1512(c)(2) after he forged a court order and sent it to an opposing party intending to cause (and in fact causing) that party to withdraw a mandamus petition then pending before an appellate court. 479 F.3d at 183, 185-87. Just as the defendant in Reich violated Section 1512(c)(2) by “inject[ing] a false order into ongoing litigation to which he was a party,” id. at 186, the superseding indictment alleges that the defendant and his co-conspirators created fraudulent electoral certificates that they intended to introduce into the congressional proceeding on January 6 to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election. See ECF No. 226 at ¶¶ 50-66.

That’s the primary reason I didn’t even treat Trump’s filing with much attention: it ignored how differently situated Trump is than the Fischer defendants.

But I’m most interested in the way Smith rebuts Trump’s argument that he bears no responsibility for the riots at the Capitol. He adopts that same aid and abet theory that Judge Mehta endorsed back in 2022.

Contrary to the defendant’s claim (ECF No. 255 at 7) that he bears no factual or legal responsibility for the “events on January 6,” the superseding indictment plainly alleges that the defendant willfully caused his supporters to obstruct and attempt to obstruct the proceeding by summoning them to Washington, D.C., and then directing them to march to the Capitol to pressure the Vice President and legislators to reject the legitimate certificates and instead rely on the fraudulent electoral certificates. See, e.g., ECF No. 226 at ¶¶ 68, 79, 82, 86-87, 94. Under 18 U.S.C. § 2(b), a defendant is criminally liable when he “willfully causes an act to be done which if directly performed by him or another would be” a federal offense. See, e.g., United States v. Hsia, 176 F.3d 517, 522 (D.C. Cir. 1999) (upholding a conviction for willfully causing a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001). [my emphasis]

Smith then repeats that language of “willfully caus[ing]” people to storm the Capitol.

As described above, the superseding indictment alleges that the defendant willfully caused others to violate Section 1512(c)(2) when he “repeated false claims of election fraud, gave false hope that the Vice President might change the election outcome, and directed the crowd in front of him to go to the Capitol as a means to obstruct the certification,” ECF No. 226 at ¶ 86, by pressuring the Vice President and legislators to accept the fraudulent certificates for certain states in lieu of those states’ legitimate certificates. Those allegations link the defendant’s actions on January 6 directly to his efforts to corruptly obstruct the certification proceeding and establish the elements of a violation of Section 1512(c)(2), which suffices to resolve the defendant’s motion to dismiss on statutory grounds. [my emphasis]

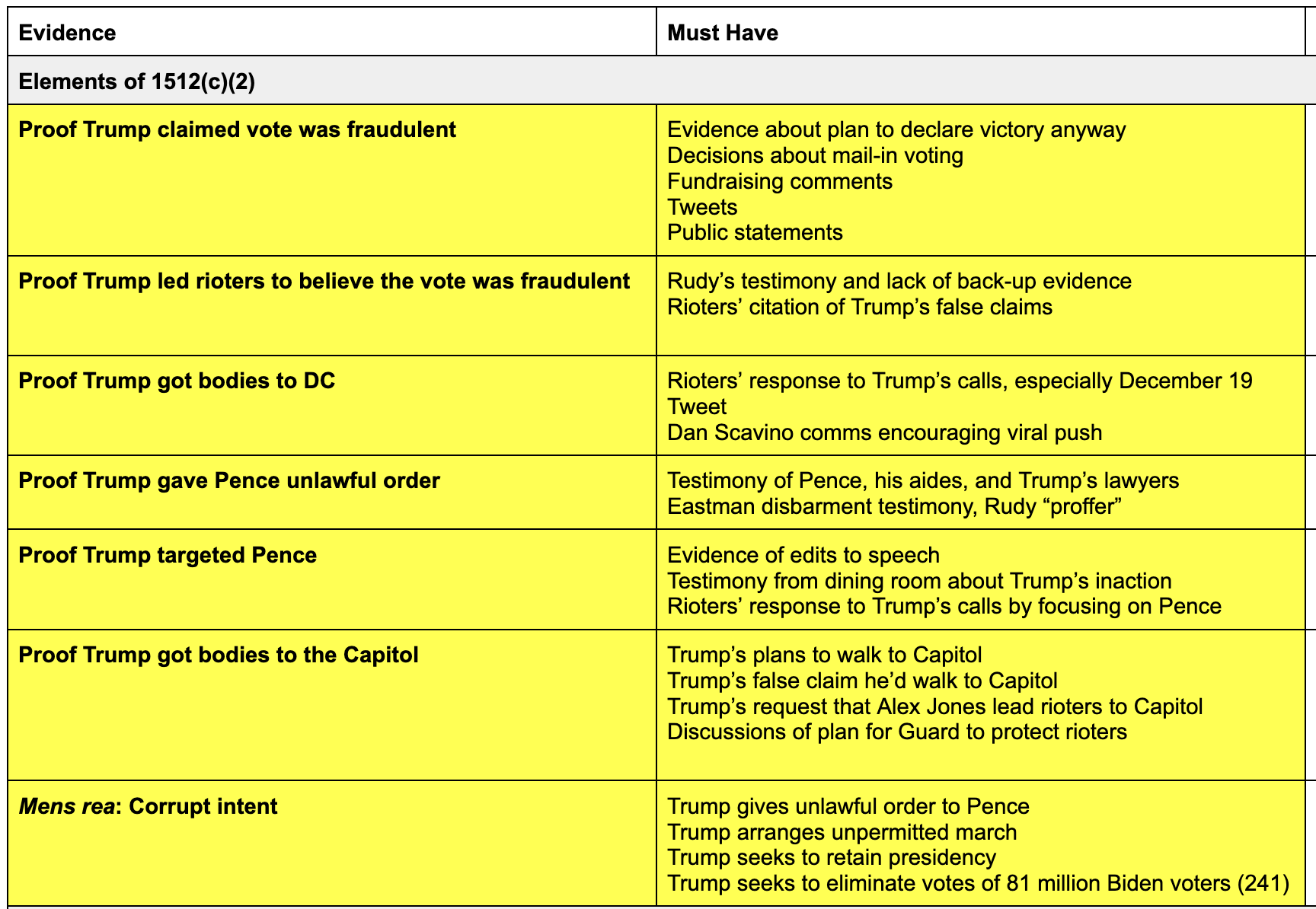

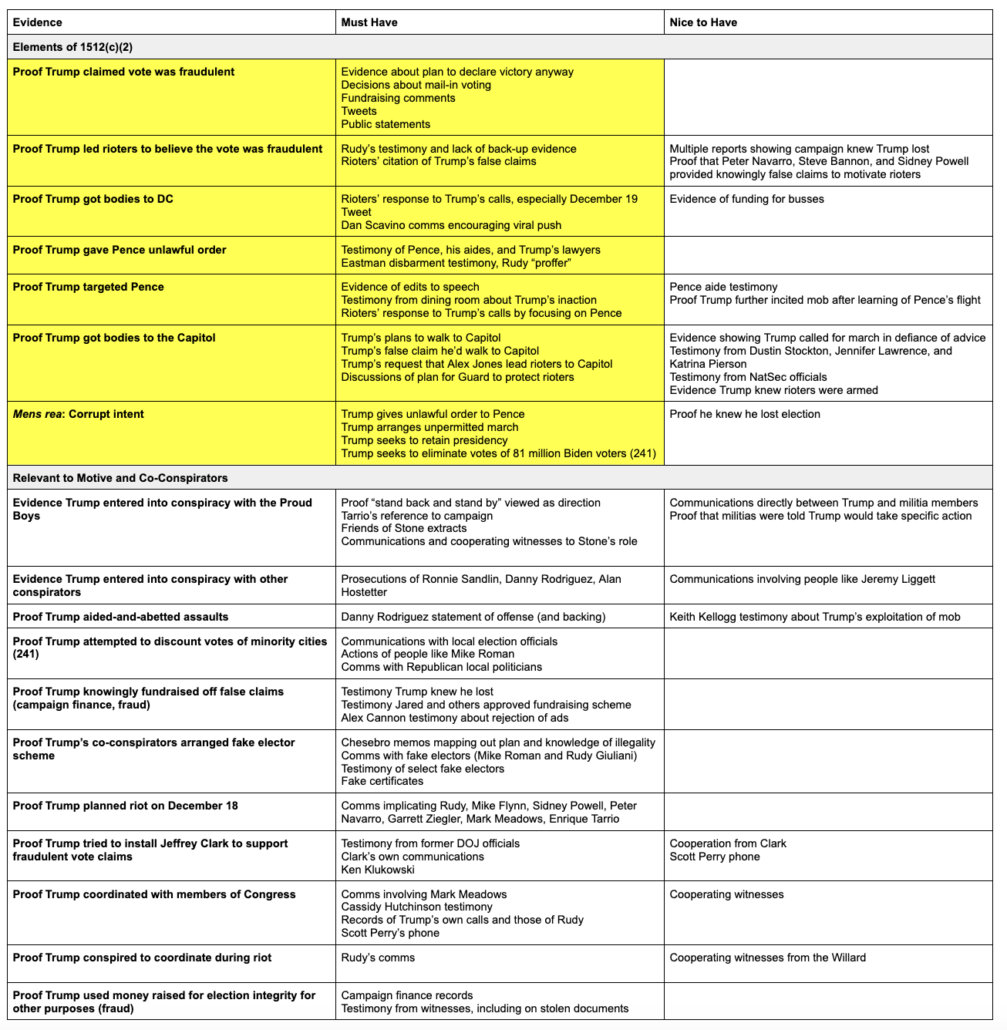

Note that this reliance on an abetting theory of liability for the riot explains DOJ’s effort to sustain some select 1512(c)(2) charges against crime scene defendants. Smith will want to closely tie Trump to the actions of key crime scene defendants.

But that depends on sustaining at least some of those key cases. But they’ve already taken at least some steps to do that. In at least one case, cooperating Oath Keeper Jon Schaffer, they’ve done an addendum to the statement of facts to sustain the plea under Fischer.

Perhaps relatedly, the nature of Schaffer’s cooperation remains redacted in the government sentencing memo asking for probation for Schaffer.

For over a year, Trump’s team has been trying to disavow his mob, and for almost a year, prosecutors have promised to show how Trump obstructed the vote certification through the actions of specific rioters.

At trial, the Government will prove these allegations with evidence that the defendant’s supporters took obstructive actions at the Capitol at the defendant’s direction and on his behalf. This evidence will include video evidence demonstrating that on the morning of January 6, the defendant encouraged the crowd to go to the Capitol throughout his speech, giving the earliest such instruction roughly 15 minutes into his remarks; testimony, video, photographic, and geolocation evidence establishing that many of the defendant’s supporters responded to his direction and moved from his speech at the Ellipse to the Capitol; and testimony, video, and photographic evidence that specific individuals who were at the Ellipse when the defendant exhorted them to “fight” at the Capitol then violently attacked law enforcement and breached the Capitol.

The indictment also alleges, and the Government will prove at trial, that the defendant used the angry crowd at the Capitol as a tool in his pressure campaign on the Vice President and to obstruct the congressional certification. Through testimony and video evidence, the Government will establish that rioters were singularly focused on entering the Capitol building, and once inside sought out where lawmakers were conducting the certification proceeding and where the electoral votes were being counted. And in particular, the Government will establish through testimony and video evidence that after the defendant repeatedly and publicly pressured and attacked the Vice President, the rioting crowd at the Capitol turned their anger toward the Vice President when they learned he would not halt the certification, asking where the Vice President was and chanting that they would hang him. [my emphasis]

As I’ve said, I think Jack Smith may believe he has the evidence to prove Trump more actively incited violence, but was prevented from indicting that before the election. But for now, Smith is making it explicit that he is adopting the theory of liability that Judge Mehta ruled was at least plausible, years ago.