On Steve Bannon’s Epically Bad Faith

The government’s sentencing memo for Steve Bannon, which asks Judge Carl Nichols to sentence Bannon to six months in prison for blowing off the January 6 Committee subpoena, mentions his bad faith thirteen times (and his failure to make any good faith effort once).

From the moment that the Defendant, Stephen K. Bannon, accepted service of a subpoena from the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol (“the Committee”), he has pursued a bad-faith strategy of defiance and contempt.

[snip]

The factual record in this case is replete with proof that with respect to the Committee’s subpoena, the Defendant consistently acted in bad faith and with the purpose of frustrating the Committee’s work.

[snip]

For his sustained, bad-faith contempt of Congress, the Defendant should be sentenced to six months’ imprisonment—the top end of the Sentencing Guidelines’ range—and fined $200,000—based on his insistence on paying the maximum fine rather than cooperate with the Probation Office’s routine pre-sentencing financial investigation.

[snip]

When his quid pro quo attempt failed, the Defendant made no further attempt at cooperation with the Committee—speaking volumes about his bad faith.

[snip]

Throughout the pendency of this case, the Defendant has exploited his notoriety—through courthouse press conferences and his War Room podcast—to display to the public the source of his bad-faith refusal to comply with the Committee’s subpoena: a total disregard for government processes and the law.

[snip]

The Defendant’s contempt of Congress was absolute and undertaken in bad faith.

[snip]

The Defendant’s claim for acceptance of responsibility is contradicted by his sustained bad faith.

[snip]

As Mr. Costello informed the Select Committee on July 9, 2022, “[the Defendant] has not had a change of posture or of heart.” Ex. 17. Mr. Costello could not have put it more perfectly: the Defendant has maintained a contemptuous posture throughout this episode and his bad faith continues to this day.

[snip]

Not once throughout this episode has the Defendant even tried to collect a document to produce, and he has never attempted in good faith to arrange to appear for a deposition.

[snip]

The Defendant hid his disregard for the Committee’s lawful authority behind bad-faith assertions of executive privilege and advice of counsel in which he persisted despite the Committee’s—and counsel for the former President’s—straightforward and clear admonishments that he was required to comply.

[snip]

Here, the Defendant’s constant, vicious barrage of hyperbolic rhetoric disparaging the Committee and its members, along with this criminal proceeding, confirm his bad faith.

[snip]

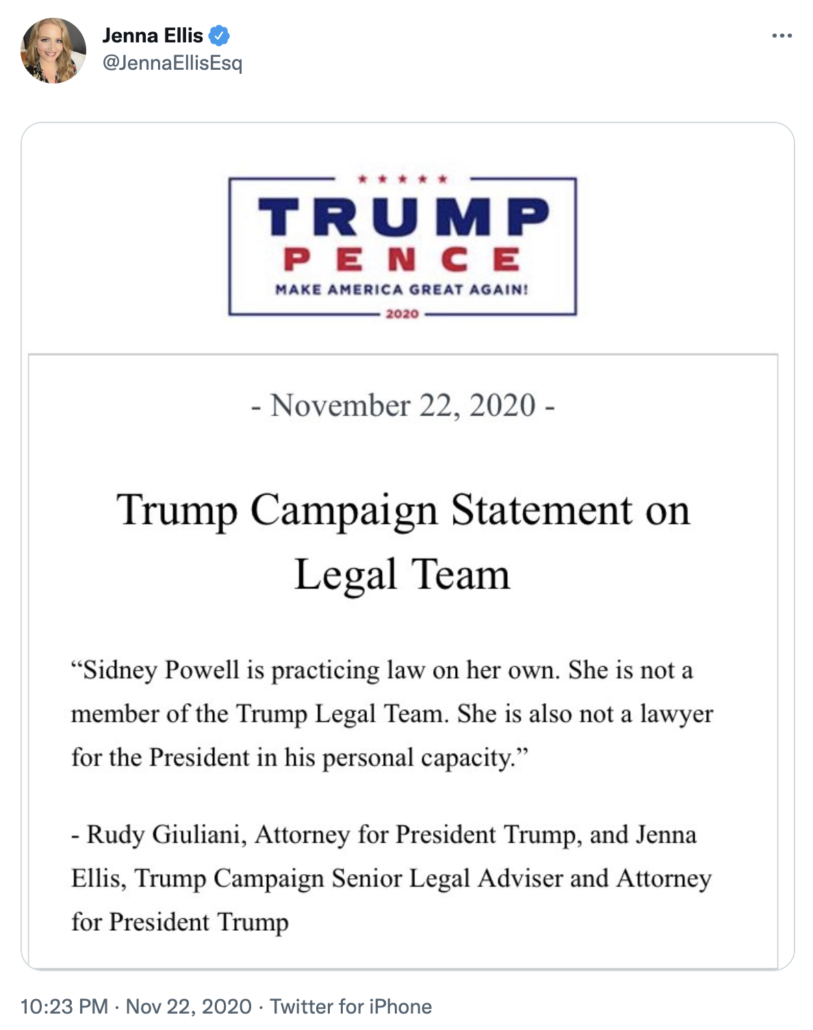

The Defendant here, by contrast, has never taken a single step to comply with the Committee’s subpoena and has acted in bad faith throughout by claiming he was merely acting on former President Trump’s instructions—even though former President Trump’s attorney made clear he was not.

[snip]

And any sentence below the six-month sentence imposed in Licavoli would similarly fail to account for the full extent of the Defendant’s bad faith in the present case.

[snip]

The Defendant’s bad-faith strategy of defiance and contempt deserves severe punishment

To substantiate just how bad his bad faith is, the memo includes a list of all the public attacks he made on the process, just three of which are:

On June 15, 2022, after a motions hearing, the Defendant exited the courthouse and announced that he looked forward to having “Nancy Pelosi, little Jamie Raskin, and Shifty Schiff in here at trial answering questions.” See “Judge rejects Bannon’s effort to dismiss criminal case for defying Jan. 6 select committee,” Politico, June 15, 2022, available at https://www.politico.com/news/2022/06/15/judge-rejects-bannons-effortto-dismiss-criminal-case-for-defying-jan-6-select-committee-00039888 (last viewed Oct. 16, 2022).

Shortly before trial, on a July 12 episode of his podcast, the Defendant urged listeners to pray for “our enemies” because “we’re going medieval on these people, we’re going to savage our enemies. See Episode 1996, War Room: Pandemic, July 12, 2022, Minute 16:37 to 17:46, available at https://warroom.org/2022/07/12/episode-1996- pfizer-ccp-backed-partners-elon-musk-trolls-trump-alan-dershowitz-on-partisanamerica-and-the-constitution-informants-confirmed-at-j6/ (episode webpage last accessed Oct. 16, 20222 ).

During trial, on July 19, the Defendant gave another courthouse press conference, in which he accused Committee Chairman Rep. Bennie Thompson of “hiding behind these phony privileges,” ridiculed him as “gutless” and not “man enough” to appear in court, and mocked him as a “total absolute disgrace.” The Defendant also teased Committee member Rep. Adam Schiff as “shifty Schiff” and another member of Congress, Rep. Eric Swalwell, as “fang fang Swalwell.” He went on to say that “this show trial they’re running is a disgrace.” See “Prosecutors say Bannon willfully ignored subpoena,” Associated Press Archive, July 24, 2022, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SR_EJL5nkw (last accessed Oct. 16, 2022).

It also describes how Bannon refused to tell the Probation office how much money he had; DOJ used that refusal to ask for a $200,000 fine as a result.

Even now that he is facing sentencing, the Defendant has continued to show his disdain for the lawful processes of our government system, refusing to provide financial information to the Probation Office so that it can properly evaluate his ability to pay a fine. Rather than disclose his financial records, a requirement with which every other defendant found guilty of a crime is expected to comply, the Defendant informed Probation that he would prefer instead to pay the maximum fine. So be it. This Court should require the Defendant to comply with the bargain he proposed when he refused to answer standard questions about his financial condition. The Court should impose a $100,000 fine on both counts—the exact amount suggested by the Defendant.

The most interesting details about the memo, however, are the inclusion of an effort Bannon made in July to get the Committee to help him delay the trial for immediate cooperation. DOJ included both an interview report and the notes Committee investigative counsel Tim Heaphy took after Evan Corcoran — the lawyer Bannon shares with Trump — tried to get the Committee to help him out in July.

HEAPHY described the overall “vibe” of his conversation with CORCORAN as defense counsel’s attempt to solicit the Select Committee’s assistance in their effort to delay BANNON’s criminal trial and obtain a dismissal of the Contempt of Congress charges pending against him.

In his notes, Heaphy suggested that DOJ might offer Bannon a cooperation plea in July.

My takeaway is that Bannon knows that this proposal for a continuance and ultimate dismissal of his trial is likely a non-starter, which prompted him to call us to explore support as leverage. I expect that DOJ will not be receptive to this proposal, as he is guilty of the charged crime and cannot cure his culpability with subsequent compliance with the subpoena. I won’t be surprised if DOJ is willing to give Bannon a cooperation agreement as part of a guilty plea. In other words, DOJ may allow Bannon to plead to one count and consider any cooperation in formulating their sentencing recommendation.

What I find most interesting about this is the date: the interview was October 7. Either DOJ did this interview just for sentencing. Or they conducted the interview as part of an ongoing investigation.

Update: Here’s Bannon’s memo. His bid for probation is not good faith given the mandatory sentence. But his request for a stay of sentence pending appeal is virtually certain to work because, as Bannon quotes heavily, Nichols thinks Bannon has a good point about relying on advice from counsel.

“I think that the D.C. Circuit may very well have gotten this wrong; that makes sense to me, what you just said. The problem is, I’m not writing on a clean slate here.” Hr’g Tr. 35:25-36:3, Mar. 16, 2022.

“The defendant was charged with violating 2 US Code Section 192. As relevant here, that statute covers any individual who “willfully makes default” on certain Congressional summonses. The defendant argues he’s entitled to argue at trial that he cannot have been “willfully” in default, because he relied in good faith, on the advice of counsel, in not complying with the Congressional subpoena. He points to many Supreme Court cases defining “willfully,” including Bryan v. United States, 524 U.S. 184, 1998, to support his reading of the statute. If this were a matter of first impression, the Court might be inclined to agree with defendant and allow this evidence in. But there is binding precedent from the Court of Appeals, Licavoli v. United States, 294 F.2d 207, D.C. Circuit 1961, that is directly on point.” Id. at 86:25-87:15.

“Second, the defendant notes that in the sixth [sic] decade since Licavoli, the Supreme Court has provided clarity on the meaning of “willfully” in criminal statutes. Clarity that favors defendant. That might very well be true. But none of that precedent dealt with the charge under 2 U.S. Code, Section 192. Licavoli did. Thus, while this precedent might furnish defendant with arguments to the Court of Appeals on why Licavoli should be overruled, this court has no power to disregard a valid and on-point or seemingly onpoint holding from a higher court.” Id. at 89:3-12.

“I noted in my prior decision that I have serious questions as to whether Licavoli correctly interpreted the mens rea requirement of “willfully”, but it nevertheless remains binding authority.” Hr’g Tr. 126:6-9, June 15, 2022.