NYT’s Limited Understanding of Trump’s “Tactics for Avoiding a Crisis Like the One He Now Faces”

There’s a funny passage in the 2,800-word NYT piece contrasting how Trump has managed Michael Cohen and Allen Weisselberg.

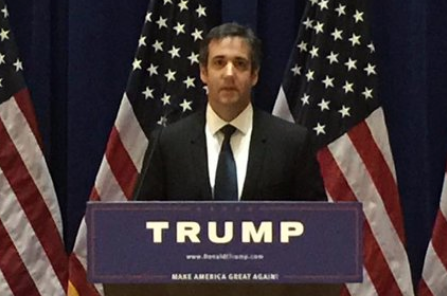

Initially sympathetic, Mr. Trump called Mr. Cohen a “good man” and the search “a disgraceful situation.” He also called Mr. Cohen with a message — stay strong — and the Trump Organization paid for Mr. Cohen’s main lawyer.

But Mr. Trump’s advisers were concerned about witness tampering accusations and he stopped reaching out. Their relationship soon soured.

NYT claims — apparently intending this to be a serious explanation — that Trump stopped trying to buy Cohen’s silence with a pardon and payments for a lawyer because of concerns about witness tampering.

I mean, I’m sure some of NYT’s sources claimed that. But given the amount of witness tampering Trump continued to engage in — publicly and privately — after leaving Cohen to fend for himself, the explanation is not remotely credible.

A far, far more likely explanation — one that is also more consistent with other aspects of NYT’s story — is that Trump and his attorneys intervened in the privilege review of phone content seized from Michael Cohen to conduct a risk assessment. (NYT says it relied on court records to tell this story, but they don’t mention that Trump abandoned Cohen only after getting access to what had been seized and why.) What Trump’s team saw before them in both the seized materials and the warrants used to seize Cohen’s devices may have led Trump to conclude, first, that Cohen had already showed signs of betrayal, by secretly recording the phone call over which they planned the hush payments to Karen McDougal.

Mr. Cohen’s lawyers discovered the recording as part of their review of the seized materials and shared it with Mr. Trump’s lawyers, according to the three people briefed on the matter.

“Obviously, there is an ongoing investigation, and we are sensitive to that,” Mr. Cohen’s lawyer, Lanny J. Davis, said in a statement. “But suffice it to say that when the recording is heard, it will not hurt Mr. Cohen. Any attempt at spin cannot change what is on the tape.”

NYT (including Maggie Haberman, who was also part of this story) was the first to break that story, and did so in the days after Cohen hired Lanny Davis, but it is not mentioned here.

Perhaps more importantly, Trump would have gotten a misleading sense from reviewing seized materials that Cohen was only being actively investigated for the taxi medallions and the hush payment.

That warrant may have led Trump to sincerely believe that prosecutors were only looking at the hush payment and business-related crimes, as he claimed on Fox News.

When Mr. Trump called into one of his favorite television shows, “Fox & Friends,” a few weeks after the search, he distanced himself from Mr. Cohen, who he said had handled just “a tiny, tiny little fraction” of his legal work, adding: “From what I understand, they’re looking at his businesses.”

“I’m not involved,” Mr. Trump added three times.

The warrants against Cohen built on each other and so built on the Mueller investigation, as I laid out here and here. But the warrant overtly tied to the April 2018 seizure didn’t mention other aspects of the investigation that might have made Trump more cautious about hanging Cohen out to dry, had he seen them.

Trump would not have known that Robert Mueller had succeeded in doing something SDNY does not seem to have done: accessed Cohen’s Trump Organization emails from Microsoft, thereby discovering documents regarding Trump’s ties to Russia that Trump Org had withheld from subpoena responses. Trump would not have known, then, that Mueller had established that Cohen told Congress a false story to cover up Trump’s own lies about Russia. That led to the first damning testimony from Cohen about Trump: That on his behalf, Cohen had contacted the Kremlin during the 2016 election and then lied to cover it up.

Plus, if Trump used the privilege review as a means to assess risk, it was based on a faulty assumption, an assumption mirrored in the NYT story.

NYT ties Cohen’s import as a witness to the crimes for which Cohen was investigated personally, even focusing exclusively on the hush payment and ignoring the lies about Russia. In a description of the damage Cohen’s congressional testimony did to Trump, NYT suggests that damage was limited to the hush payment, the thing that Trump allegedly engaged in financial fraud to cover up (predictably, NYT doesn’t mention the financial fraud alleged in the cover-up, just the cover-up).

When he pleaded guilty to federal charges that August, Mr. Cohen pointed the finger at Mr. Trump, saying he had paid the hush money “at the direction of” his former boss — an accusation he is expected to repeat on the witness stand in the Manhattan trial. A spokeswoman for Alvin L. Bragg, the Manhattan district attorney, declined to comment.

Before going to prison, Mr. Cohen also appeared before Congress, where he was asked who else had worked on the hush-money deal. His answer: Mr. Weisselberg.

The far more damaging thing Cohen did in that congressional testimony, though, was to tee up the way Trump adjusted his own business valuations he used for his business to maximize his profits. That was the basis for the fraud trial against Trump Org, and if the verdict sticks, it may cost Trump a half billion dollars and, unless he finds a way to cash in on Truth Social, may create follow-on financial problems.

In other words, Trump seems to have imagined Cohen would not find another way of avenging being hung out like he was, and NYT doesn’t include that other way — predicating investigations that threaten Trump Org itself and led to Weisselberg’s twin prosecutions — in their story.

Ultimately, NYT is still telling this story as if the newsworthy bit is Trump’s continued success at cheating the law, what they describe as, “the power and peril of Mr. Trump’s tactics for avoiding a crisis like the one he now faces.”

This “power and peril” pitch makes Trump the hero of the story and Cohen and Weisselberg contestants in a reality show, with Cohen inflating that contest with his wildly premature boast that “the biggest mistake” Trump ever made was not paying for Cohen’s defense and his claim, “I was the first lamb led to the slaughterhouse.”

If NYT weren’t making this a reality show, it might take away different lessons:

- Trump has invested a great deal in using associates and co-conspirators to learn of the criminal investigation into him, with a Joint Defense Agreement incorporating 37 people during the Mueller investigation and $50 million of Republican campaign funds invested instead in paying attorneys who will at a minimum report back on investigative developments. Even with that $50 million investment (and the potential damage it’ll do to GOP fortunes in November), Trump has fewer tools to discover the status of ongoing investigations than he had when Republicans on both Intelligence Communities were using the committee to spy on investigations for him. Yet even with far more access to information than he currently has about ongoing investigations (the two federal cases against Trump are different, because Jack Smith has overproduced discovery), Trump miscalculated with Cohen.

- The risk Cohen posed was not just — as NYT portrays — that he’ll testify against Trump at trial, at this trial. It was that he would disclose information that implicated Trump (and Weisselberg) in new investigations, as he did. As such, one lesson to take away from this, at least for those who don’t have an incentive to make Trump the protagonist of all stories, is that those spurned by Trump know a whole lot of shit about him, and that shit could turn into investigations that implicate the fraud that lies at the core of his persona. John Bolton, Mike Esper, and Mike Pence are all people whom Trump accused of disloyalty who thus far have only shared shit about Trump when prosecutors came asking. That could change.

- As noted, NYT didn’t mention that Trump only turned on Cohen after discovering that prosecutors had obtained a damning recording from his phone. But he’s not the only Trump associate whose own blackmail on Trump was implicated in a criminal investigation. Mueller’s prosecutors were seeking Stone’s notes of all the calls he had with Trump during the 2016 election when they searched his homes (it’s not clear whether they ever found it), the existence to which Steve Bannon was also a witness. Both Stone and Bannon got their pardons, perhaps because they were better able at leveraging dirt on Trump for legal impunity than Cohen was.

- NYT describes the injury to Trump here as, “his long-held fear that prosecutors would flip trusted aides into dangerous witnesses.” That’s just weird. It’s as if NYT hasn’t considered that the real danger is that he’ll do prison time for his crimes. The focus on loyalty rather than truthful testimony is especially odd in a piece that describes that Hope Hicks is likely to testify in Alvin Bragg’s case, who’ll testify with less of the circus and more credibility than Cohen. After all, even Jason Miller, still a top campaign manager for Trump, would be a key witness against Trump in a January 6 trial if he repeated the true description of how the campaign started refusing to support the Big Lie after a period in 2020. Bannon provided damaging testimony in the Roger Stone trial by being held to his prior grand jury testimony, and he remains a MAGAt in good standing.

Sometimes, it’s not disloyalty that can sustain a conviction, it’s truth, even truth from still-loyal associates.

Not for NYT, I guess. In a piece trying to extend this analogy to Walt Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira (the latter of whom, who really does have a colorable claim he didn’t know he was obstructing an investigation, is not similarly situated in my opinion), NYT describes that they were charged for their loyalty, not claims that sound pretty obviously false in the indictment.

Like Mr. Weisselberg, Mr. Nauta and Mr. De Oliveira remained loyal, and they are now paying the price: Mr. Smith charged both men not only with obstruction of justice, but also with lying to investigators.

Nauta and De Oliveira got charged, in part, because prosecutors believe they lied to protect Trump because that is a crime, just like it was a crime when Cohen and Stone and Mike Flynn and George Papadopoulos and Paul Manafort did it (Manafort was punished but not charged for those lies). But Nauta, especially, almost certainly got charged because prosecutors still haven’t been able to account for how much Trump intended to steal classified documents when he left the White House and still haven’t been able to account for the stolen classified documents that got flown to Bedminster in 2022. Nauta probably figures it’s a good bet to hope that Trump wins the presidency, ends his prosecution (or pardons him) and rewards him with a sinecure. That’s how having dirt on Trump works! But the prosecution is not over yet, and especially given the likelihood that this won’t go to trial before the election, he may change his mind.

Trump has absolutely succeeded in bolloxing all his criminal cases and may well succeed in delaying all the rest until he can pardon his way out of most of them. But if that effort fails, basic rules of gravity are likely to kick in and Trump will no more be a protagonist than all the other suspected criminals investigated by state and federal authorities.