Will the Saudis Let JSOC Take Over Yemeni Targeting?

There were three airstrikes in Yemen this week, with the last being a strike in al-Jawf, a province on the Saudi border, that local observers have variously described as a drone strike and a Saudi jet strike.

Keep ongoing confusion about airstrike attribution in mind as you read this Greg Miller article. It purportedly examines how easy it will be to cede CIA control over drones to DOD. But Miller focuses on Yemen, where, as he portrays it, the question of CIA control over drone strikes is inescapably tied to use of the Saudi base to launch them.

As Miller describes, after initially intending to keep JSOC in charge of strikes in Yemen, the Administration shifted to the CIA because of some serious fuck-ups, among them the al-Majala strike, which killed a Bedouin tribe, the May 2010 strike that took out the Deputy Governor of Shabwah province (probably on deliberately bad intelligence), and the May 2011 attempt that allowed Anwar al-Awlaki to escape.

The change was driven by a number of factors, including errant strikes that killed the wrong people, the use of munitions that left shrapnel with U.S. military markings scattered about target sites and worries that Yemen’s unstable leader might kick the Pentagon’s planes out.

But President Obama’s decision also came down to a determination that the CIA was simply better than the Defense Department at locating and killing al-Qaeda operatives with armed drones, according to current and former U.S. officials involved in the deliberations.

The first two of these fuck-ups almost certainly came from the intelligence sharing process. Yet one of Miller’s sources describes it as a problem with DOD’s kinetic skills, the actual targeting of drones.

“I never fully understood why they struggled so much,” the former official said, referring to the Pentagon’s problems. “Of all the pieces, the kinetic piece at the end was what they should have been good at.”

Given the chronology Miller’s story lays out, it was this last strike, the only one that represented an actual kinetic rather than intelligence failure, that led the Administration to decide to go to the Saudis.

Miller then lays out the thin kabuki the Saudis engaged in to claim this wasn’t a new expansion of US military presence on Saudi soil (as if building a 35,000 person infrastructure protection force, developed under the leadership of a US Major General, were not also one). And he describes the deal the Saudis struck: they’re in charge.

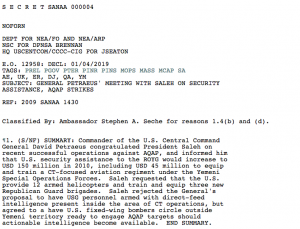

The Saudi government imposed conditions, including full authority over the facility and assurances that there would be no U.S. military personnel on site. The operation would be run by the CIA and Saudi intelligence, who for years had jointly operated a fusion center in Riyadh.

But it’s the excuses used to rule out JSOC drones that are most telling. JSOC couldn’t be involved, the kabuki claims, because it would involve a more tedious vetting process.

Feeding targeting intelligence to JSOC drones was not seen as a valid option, in part because doing so would require military approvals that could bog down a process requiring split-second decisions, officials said.

“The military’s culture is very uncomfortable with someone not in the chain of command handing them a target package and saying, ‘Hit this,’ ” said Jeremy Bash, who served as a senior aide to Panetta at the Pentagon and the CIA.

The first CIA flights began in August 2011. Six weeks later, Awlaki was killed in a CIA strike.

Voila! DOD no longer vets drone targeting and Awlaki dies within weeks!

Funny how that worked out.

Miller then lays out several of the advantages CIA purportedly has over DOD. In addition to the longevity of command at CIA’s counterterrorism center as compared to JSOC, he also cites CIA’s involvement in infiltrating terrorist organizations like al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

Among them is its expertise at penetrating terrorist groups through networks of informants, and the expertise of officers and analysts who tend to stay in their assignments longer than their military counterparts.

Of course, CIA doesn’t do that by itself in Yemen. It does it with the Saudis and the Yemenis. And always has.

Indeed, the Saudis were involved in at least one of the fuck-ups given as reason to switch to the Saudi base. The Yemenis probably dealt us the bad intelligence that killed the Deputy Governor of Shabwah.

Now, I’m willing to entertain the possibility that moving to CIA targeting under Saudi control is mostly about bypassing Yemeni vetting, as I’ve suggested before. But it is also the case that some of our more recent drone strikes took out people, like that Deputy Governor, who had reportedly served as mediators between extremists and the government in the past, so it is not entirely clear that putting the Saudis in charge has resulted in better targeting.

But we are doing what the Saudis asked us to do 4 years ago, giving them drone intelligence, if not drone kills, they can use to target Saudi enemies in the north of Yemen.

It’s fairly clear that CIA will remain in charge of drone strikes in Pakistan at least through the official pull-out of US troops from Afghanistan. But whether or not the CIA — and with them, the Saudis — will retain control of Yemeni targeting is a far more interesting question going forward.