In this post, I noted all the things in DOJ’s reply on their motion for a Garcia hearing that had to have come from the grand jury, and assumed that DC Chief Judge James Boasberg must have permitted DOJ to share it.

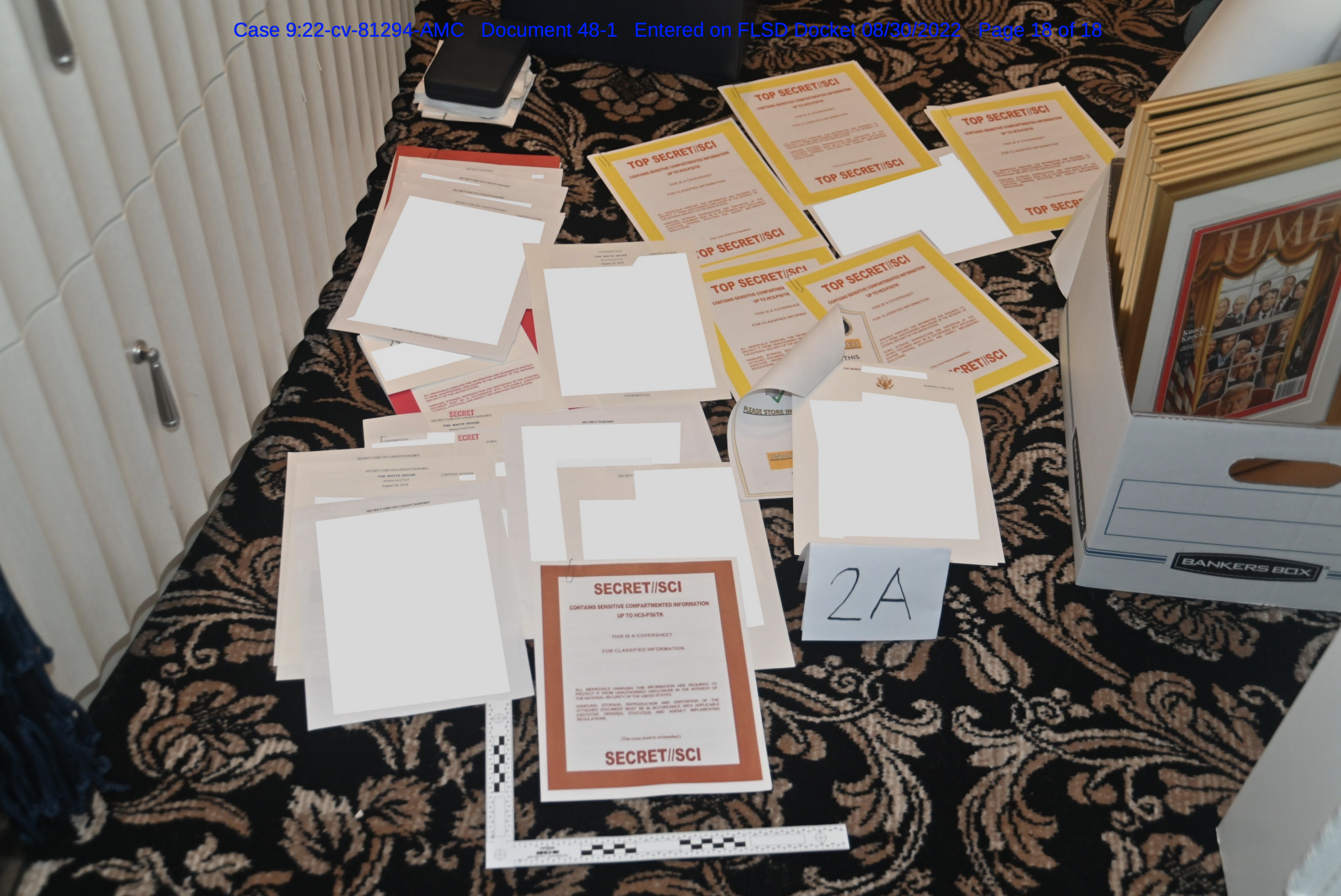

As described here, yesterday’s reply on the motion for a Garcia hearing in the stolen documents case revealed a good deal of grand jury information about Yuscil Taveras’ testimony.

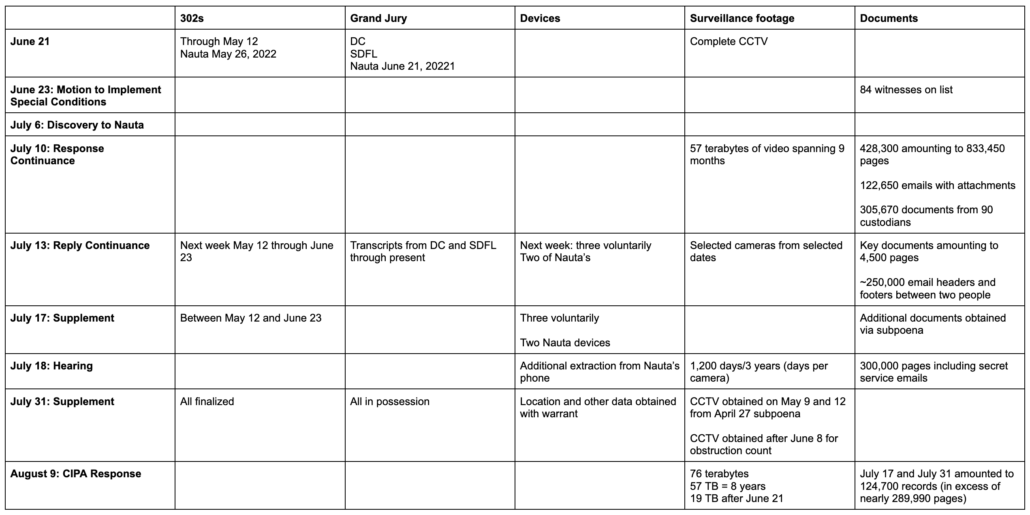

It revealed:

- Trump’s IT worker, Taveras, testified (falsely, the government claims) in March

- DOJ obtained two more subpoenas for surveillance footage, on June 29 and July 11, 2023 (the existence of those subpoenas, but not the date, had already been disclosed in a discovery memo)

- It included the docket number associated with the conflict review — 23-GJ-46 — and cited Woodward’s response to the proceedings

- James Boasberg provided Taveras with conflict counsel

- Taveras changed his testimony after consulting with an independent counsel

Under grand jury secrecy rules, DC Chief Judge Boasberg would have had to approve sharing that information, but the docket itself remains sealed and Boasberg has not unsealed any of the proceedings.

A filing submitted from DOJ shows that I was right.

It also shows that Judge Aileen Cannon and Walt Nauta attorney Stan Woodward are engaged in a game that is doing nothing to ensure that Nauta’s getting unconflicted legal representation, but it is protecting Trump’s protection racket.

Let’s review the timeline.

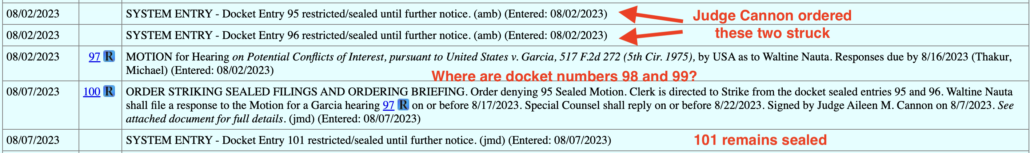

On August 2, DOJ filed their original motion for a Garcia hearing, describing, generally, that Yuscil Taveras had testified against Nauta, which presented a conflict for Woodward, even before you consider the three other possible trial witnesses — of seven remaining witnesses — he also represents. DOJ submitted a sealed supplement with information on those three as well as other information, “to facilitate the Court’s inquiry.” Five days later, Cannon ordered that filing stricken, stating that, the government had, “fail[ed] to satisfy the burden of establishing a sufficient legal or factual basis to warrant sealing the motion and supplement.” In her drawn out briefing schedule on the question, she instructed Stan Woodward to address, “the legal propriety of using an out-of-district grand jury proceeding to continue to investigate and/or to seek post-indictment hearings on matters pertinent to the instant indicted matter in this district.”

On August 17, Woodward responded. He contended that Garcia hearings only covered when an attorney represented two defendants, but ultimately argued that, rather than adopt a more traditional method of resolving such a conflict (such as replacing Woodward), Judge Cannon should exclude Taveras’ testimony.

The government’s reply — filed on August 22 — is the one that made public more, damning, information on what went down in June and July.

Three more days passed before Woodward submitted a furious motion requesting opportunity to file a sur-reply. In it, filed 23 days after DOJ’s original submission and sealed filing, he accused DOJ of contravening, “a sealing order issued by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia,1” though in a rambling footnote, he admitted maybe DOJ had requested to unseal this ex parte.

1. Defense counsel is not currently aware of any application by the government to unseal defense counsel’s submission. To have done so ex parte is arguably less professional than deliberately violating the Court’s sealing order. The government did not solicit defense counsel’s position on the unsealing of defense counsel’s own submission, but appears to have deliberately misled both the District Court for the District of Columbia and this Court. Of course, if they did seek such an application ex parte, this would be the second time in as many weeks that the government has done so – a particularly ironic approach given the Special Counsel’s objection to the Court conducting any ex parte inquiry of Mr. Nauta.

In a fit of Trumpist projection, Woodward also complained that DOJ was doing things that might lead to tampering with witnesses.

2 In the time since the government’s submission, defense counsel has received several threatening and/or disparaging emails and phone calls. This is the result of the Special Counsel’s callous disregard for how their unnecessary actions affect and influence the public and the lives of the individuals involved in this matter. It defies credulity to suggest that it is coincidental that mere minutes after the government’s submission, at least one media outlet was reporting previously undisclosed details that were disclosed needlessly by the government.

Projection, projection, projection.

Well, it worked. Judge Cannon granted Woodward’s motion, even giving him one more day than he asked, until August 31 instead of August 30 (remember that she scheduled a sealed hearing sometime in this timeframe). Which will mean that because of actions taken and inaction by Aileen Cannon, Walt Nauta will go the entire month of August without getting a conflict review.

Meanwhile, on August 16, DOJ filed a motion for a Garcia hearing to discuss the three witnesses represented by Carlos De Oliveira’s attorney who may testify against him. Best as I can tell, Cannon is simply ignoring that one. Fuck De Oliveira, I guess.

After Cannon assented to yet more delay before she addressed the potentially conflicted representation of two of three defendants before her (someday, Cannon may even have to deal with conflicts Todd Blanche has, since he also represents Boris Epshteyn), DOJ submitted notice sharing a filing they submitted before the DC grand jury, assenting to Woodward’s request, filed just yesterday morning (that is, three days after their reply), asking to unseal stuff that was already unsealed.

It includes the Woodward filing, from which DOJ’s reply quoted, that Woodward claims DOJ cited out of context.

The full filing doesn’t help Woodward.

Indeed, Woodward’s own filing suggests that if Taveras wanted to cooperate with the government, that would entail seeking a new attorney.

Ultimately, this is little more than a last-ditch effort to pressure [Taveras] with vague (and likely nonexistent) criminal conduct in the hopes that [Taveras] will agree to become a witness cooperating with the government in other matters. See Government Filing, p. 10 (“A conflict may arise during an investigation if a lawyer’s ‘responsibility to his other clients prevents the lawyer from exploring with the prosecutor whether it might be in the interest of one witness to cooperate with the grand jury or to seek immunity if the witness’s cooperation or testimony would be detrimental to the lawyer’s other client.’ [] ‘Professional ethics prevent [an attorney] from advising a witness to seek immunity or leniency when the quid pro quo is testimony damning to his other clients, to whom he also owes a duty of undivided fidelity[.] [] In many cases, however, that advice is precisely what the client needs to hear, even, or perhaps especially, when it ‘is unwelcome’ advice that ‘the client, as a personal matter, does not want to hear or follow.’ [] (internal citations omitted)). Ultimately, [Taveras] has been advised by counsel that he may, at any time, seek new counsel, and that includes if he ultimately decided he wanted to cooperate with the government. However, [Taveras] has not signified any such desire and that means counsel for [Taveras] can continue to represent [Taveras] both diligently and competently. [my emphasis]

And the filing makes clear that DOJ addressed at more length the conflict presented because Woodward was being paid by Save America PAC; while I’m uncertain about the local rules in SDFL, in DC there is a specific rule 1.8(e), requiring informed consent when an attorney is paid by someone else. While Woodward addressed it (see below), Woodward’s own description that Taveras could get another lawyer if he wanted to cooperate would seem to conflict with that rule’s independence of representation, and when he addresses the rule, Woodward doesn’t address confidentiality.

Furthermore, when Woodward addresses why being paid by Save America PAC is only natural for Taveras because Taveras worked for Trump, he makes an argument that wouldn’t explain the entirety of his representation for Nauta — or, for that matter, Kash Patel, a known Woodward client who testified in the stolen documents case.

While the government has often sought to imply an illicit purpose for the Save America PAC covering the legal costs of certain grand jury witnesses, the truth has always been very simple and legitimate: many of the grand jury witnesses, including [Taveras], are only subject to this investigation by virtue of their employment with entities related to or owned by Donald Trump. Save America PAC has placed no conditions on the provision of legal services to their employees. Ultimately and in compliance with Rule 1.8, [Taveras] was advised that Save America PAC would pay his legal fees, that [Taveras] could pursue other counsel than Mr. Woodward if he so desired, that Save America PAC was not Mr. Woodward’s client, that [Taveras] was Mr. Woodward’s client, and that [Taveras] could always make the decisions relating to the trajectory of [Taveras]’s grand jury testimony. [my emphasis]

Taveras is only a witness because Trump paid him to do IT work. But for much of the conduct about which Kash must have given testimony, represented by Woodward, he was the Acting Chief of Staff at the Pentagon. That’s the period when, per Kash, Trump conducted a wild declassification spree in his last days as President before packing up boxes to move to Mar-a-Lago.

And while most of Nauta’s exposure as a witness (and now defendant) arises from things Nauta did as Trump’s valet after both left the White House, ¶25 of the superseding indictment, describing the process by which Trump and Nauta packed up to leave, entails conduct from before Nauta left government employ.

If Trump were to be charged with 18 USC 2071, Nauta would be a witness to that.

In other words, brushing off the financial conflict with Taveras is one thing, but this conflict is also about Nauta. And Nauta is now being prosecuted for conduct that may have begun when American taxpayers were paying him, not Donald Trump. One of the things Nauta may be hiding by not cooperating are details about Trump’s overt intentions as they both packed up boxes.

And that’s not even the most damning part of the filing DOJ submitted yesterday.

DOJ also submitted its initial motion to unseal grand jury materials, submitted on July 30, in advance of the Garcia motion.

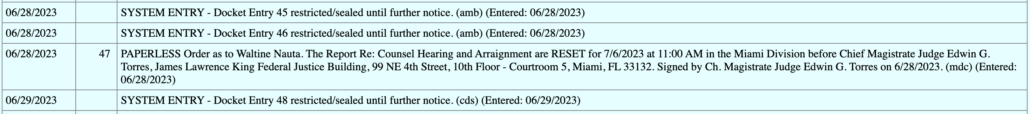

That motion reveals, first of all, that DOJ informed Judge Cannon of the conflict hearing on June 27.

On June 27, 2023, the government filed a sealed motion asking the Court to conduct an inquiry into potential conflicts of interests arising from attorney Stanley Woodward, Jr.’s simultaneous representation of [Taveras] and Waltine Nauta (“conflicts hearing motion”); and a separate sealed motion seeking Court authorization to disclose the conflicts hearing motion by, among other things, attaching a copy of the motion to a sealed notice to be filed in United States v. Donald J. Trump, Waltine Nauta, and Carlos De Oliveira, No. 23-cr-80101 (S.D. Fla.) (“Florida case”). The Court granted both motions, and the government filed the sealed notice, with a copy of the conflicts hearing motion attached, the same day.

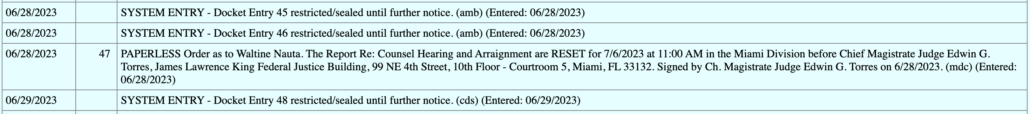

As DOJ noted in its reply, that’s what the sealed docket entries 45 and 46 are.

That is, Aileen Cannon knew this was happening in real time. DOJ wasn’t hiding anything from her.

That motion to unseal also describes that DOJ intended to file “all information related to the conflicts hearing,” including the appointment of Michelle Peterson to represent Taveras, in a sealed supplement to its motion for a Garcia hearing.

The government therefore moves for an order permitting it to disclose to the court in the Florida case all information related to the conflicts hearing, including the fact and dates of the hearing, the resulting appointment of AFPD to represent [Taveras], and, if necessary, any filings, orders, or transcripts associated with the conflicts hearing. The government initially intends to include such information only in a sealed supplement to its motion for a Garcia hearing.

In other words, these two docket entries that Judge Cannon ordered be stricken, five days after they were posted and therefore made available to both Cannon and Woodward?

They include the material that, Woodward claims, he had never seen before DOJ’s reply.

Judge Cannon just gave Woodward another bite at the apple, as well as another six days before his client gets a Garcia hearing, based off Woodward’s claim that he had never seen information DOJ had shared (and which would have been available to Woodward for five days) but then Cannon herself had removed from the record. DOJ did provide this information in its initial motion. But because of actions Cannon took — the judicial equivalent of flushing that information down the toilet — Woodward (after waiting three days himself before first asking Judge Boasberg to share the information) claimed that he had never seen it before.

DOJ may have had a sense of where this was going, because back on July 30, in the same paragraph where they asked for permission to submit this information as part of a sealed supplement, DOJ also asked for permission to share it in unsealed form if things came to that.

[T]o ensure that it does not need to return to the Court for further disclosure orders, the government also seeks authorization to disclose information related to the conflicts hearing more broadly in the Florida case, as the need arises, including in briefing and in-court statements related to the Garcia hearing.

Things did, indeed, come to that.

And Woodward may have gotten notice of all that from Judge Boasberg’s order on July 31.

Things are going to get really testy going forward (if they haven’t already under seal) because, in a filing that DOJ did not first ask permission to file (but which I suspect would be authorized by a sealed order elsewhere in the docket, not to mention general ethical obligations requiring DOJ to inform her of everything going on in DC), DOJ just revealed that Judge Cannon threw out precisely the information that she’s now using to grant Woodward’s request for a sur-reply and — between the three days he waited to ask and the six she granted him to respond — nine more days to delay such time before Walt Nauta might be told about the significance of all the conflicted representation Woodward has taken on.

But I also expect that this will escalate quickly in one or another forum. Aileen Cannon was informed weeks ago of two significant conflicts in the representation of defendants before her, and rather than attend to those conflicts (or decide, simply, that she was going to blow them off, which in some forms might be an appealable decision), she has helped Woodward simply stall any resolution to the potential conflict.

Remember how I’ve promised I would start yelling if I believed that Cannon was doing something clearly problematic to help Trump? I’d say we’re there.

Update: Corrected my own math on the delay, which I said was 11 days but is 9. Ignoring that Cannon asked for lengthy briefing on a topic that most judges would just issue an order on, the key delays are:

- 5 days before Cannon flushed the sealed supplement down the judicial toilet

- 3 days between the DOJ reply and Woodward’s panicked demand for a sur-reply based on a claim that DOJ hadn’t previously raised the things Cannon flushed

- 6 days of delay before Woodward will submit his sur-reply