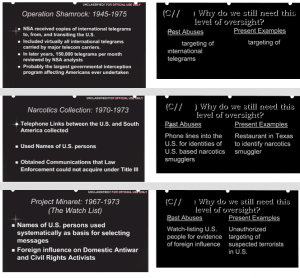

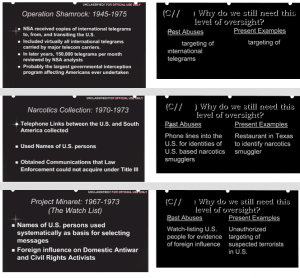

In a training program developed in 2009, the NSA itself identified abuses it likened to Projects Shamrock and Minaret.

Today, LAT has an extremely friendly exit interview with Keith Alexander that nevertheless depicts the now-retired General as hopelessly lost inside a bubble far removed from those who paid his salary. It depicts Alexander confusing objections to what NSA’s leaders have ordered with what the presumably honorable people who implement those decisions.

But something else seems likely to shape the legacy of the NSA’s longest-serving director, who retired Friday: something that Alexander failed to anticipate, did not prepare for and even now has trouble understanding.

Thanks to Edward Snowden, a former NSA contractor, the world came to know many of the agency’s most carefully guarded secrets. Ten months after the disclosures began, Alexander remains disturbed, and somewhat baffled, by the intensity of the public reaction.

“I think our nation has drifted into the wrong place,” he said in an interview last week. “We need to recognize that those who are working to protect our nation are not the bad people.“

I find it particularly troubling that Alexander sees in skepticism about authority the nation “drifting into the wrong place.”

The profile goes on to convey Alexander’s laughable belief that what has been depicted since June is the model of oversight.

When Snowden’s disclosures began, Alexander and his deputies knew they were in for a storm. But they felt sure the American public would be comforted when they learned of the agency’s internal controls and the layers of oversight by Congress, the White House and a federal court.

“For the first week or so, we all had this idea that we had nothing to be ashamed of, and that everyone who looked at this in context would quickly agree with us,” Inglis said.

Instead, polls show, many Americans believe that the NSA is reading their emails and listening to their phone calls. A libertarian group put an advertisement in the Washington transit system calling Alexander, a 62-year-old career military officer, a liar. U.S. technology companies are crying betrayal.

Side note: it would be useful if LAT noted that in fact the disclosures do show that the NSA is conducting warrantless back door searches on US person emails, rather than using the conjunction “instead” suggesting this impression is false. And that’s all before you get into the vast collection overseas and upstream for which NSA refuses to count US person data.

I’m particularly interested in Alexander’s attempt to distinguish this scandal from the scandals of the 1970s.

He sees a fundamental difference between the intelligence abuses uncovered by Congress in the 1970s — including revelations that the NSA spied without warrants on domestic dissidents — and the programs exposed by Snowden.

“What the Church and Pike committees found” nearly 40 years ago was “that people were doing things that were wrong. That’s not happening here,” Alexander said, referring to the panels headed by Sen. Frank Church (D-Idaho) and Rep. Otis Pike (D-N.Y.) that examined intelligence-agency activities in that era.

As I have noted repeatedly, 4 years into Alexander’s tenure, the NSA itself likened some of its abuses to Projects Shamrock and Minaret. So perhaps Alexander should at least cede that under his leadership, the NSA was also doing things that it itself considered to be analogues to those earlier scandals (and yes, they violated the law and limits of the programs in question).

Even the LAT conducts a soft fact check of Alexander’s claim that the President’s Review Group and PCLOB found a model of oversight.

Outside reviews, including one released in December by a presidential task force, he said, found that “lo and behold, NSA is doing everything we asked them to do, and if they screw up, they self-report.”

The task force reported it found “no evidence of illegality or other abuse of authority for the purpose of targeting domestic political activity.” But it also noted “serious and persistent instances of noncompliance” with privacy and other rules. Even if unintentional, those violations “raise serious concerns” about the NSA’s “capacity to manage its authorities in an effective and lawful manner,” the report said.

I’d go further, too, and point out that this self-reporting only came with the greater involvement of DOJ’s National Security Division, after years of NSA not reporting these violations. Even months into one of those incidents, the NSA was failing to report its violations to the FISC without NSD involvement.

But perhaps the most egregious example of Alexander’s bubble comes in his assessment of the Snowden leaks themselves.

The ease with which Snowden removed top-secret documents also embarrassed an agency that is supposed to be the first line of defense against cyberattacks.

In July, Alexander offered to resign, but the White House turned him down, he said. He didn’t think holding other senior officials accountable would be right because a massive theft of documents by a systems administrator could not have been foreseen, he added.

Are you kidding me? First, how is it that the NSA couldn’t anticipate the large scale exfiltration of documents via removable media in the 3 years after Chelsea Manning did so? And why didn’t NSA comply with requirements to implement software to prevent just that, the kind of software Alexander insists his agency should have on our private communications? But note what else doesn’t get mentioned, as Alexander rides off into the sunset of generous defense contractor sinecures? Not only didn’t Alexander hold his subordinates responsible, but he didn’t hold Booz responsible, the company under whose lucrative eyeballs Snowden did this work.

As of Friday, the Bubble General is gone into retirement. While I fully expect soon-to-be Admiral Mike Rogers to be just as aggressive in hiding the scope of his programs and doing what he can because he can, I do hope he is not this detached from the reality in which he works.