What a Properly Scoped FISA Abuse Inspector General Report Would Look Like

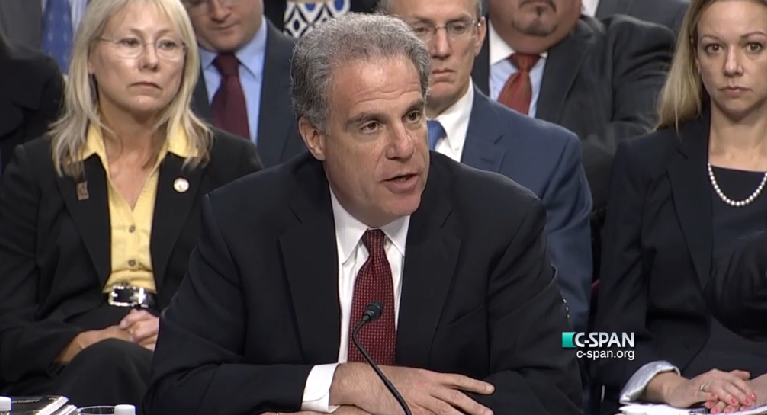

In this piece on the Jim Comey IG Report, I showed that Michael Horowitz’s department received evidence of two violations of DOJ rules. His office first received seven memos that documented that DOJ’s protocols to ensure the integrity of investigations had collapsed under Donald Trump’s efforts to influence investigations. And then, at some later time, his office learned that Comey had (improperly, according to the report) retained those memos even after being fired and that FBI had classified six words in the memos he retained retroactively.

Horowitz’s office has completed an investigation into an act that otherwise might be punished by termination that already happened. But there is zero evidence that Horowitz has conducted an investigation into the subject of the whistleblower complaint, the breakdown of DOJ’s protections against corruption.

In April 2018, Horowitz released a report (which had been hastily completed in February) detailing that Andrew McCabe had been behind a reactive media release during the 2016 election. But his office has not yet released its conclusions regarding the rampant leaks that McCabe was responding to. In other words, Horowitz seems to have once again released a report on a problem that — however urgent or not — has already been remedied, but not released a report on ongoing harm.

Horowitz is reportedly preparing to release a report on what the frothy right calls “FISA abuse.” but given the content of a Lindsey Graham letter calling for declassification of its underlying materials, it’s seems likely that that report, too, is scoped narrowly, focusing just on Carter Page (and any other Trump officials targeted under FISA). There’s no request for backup materials on the other investigation predicated off of hostile opposition research, the investigation into the Clinton Foundation.

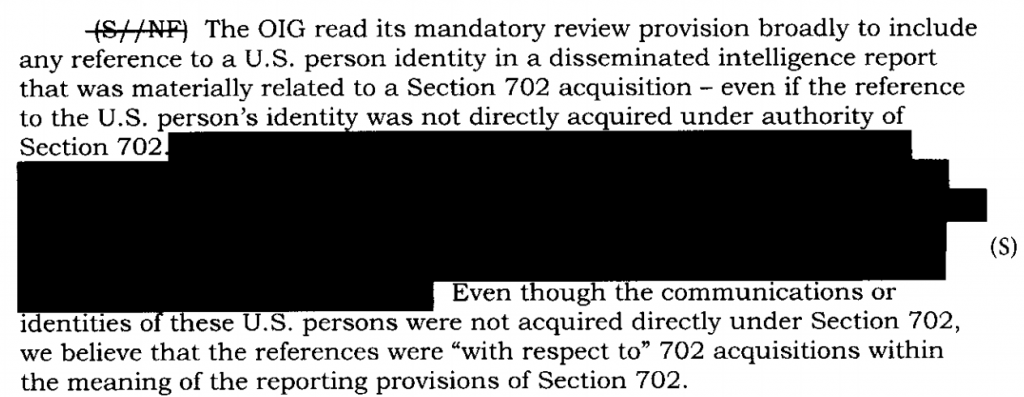

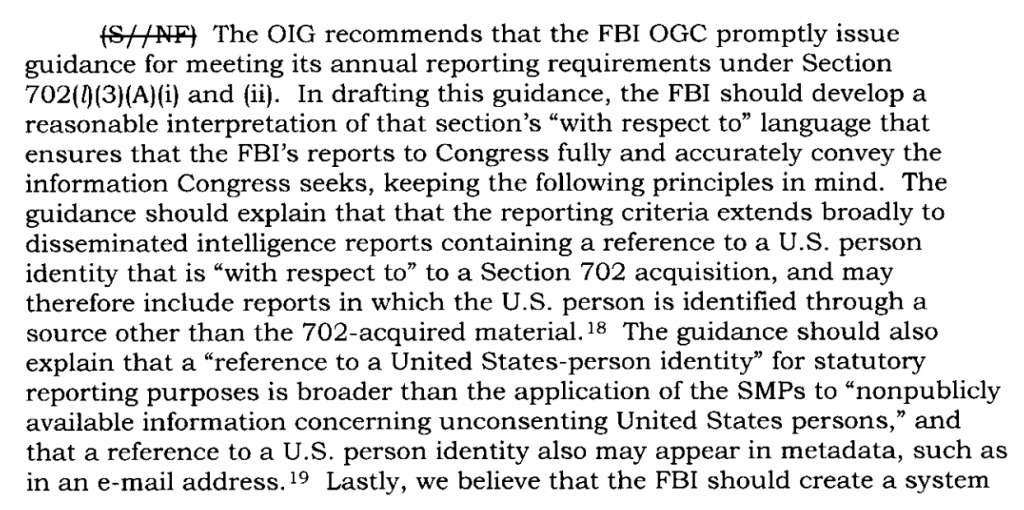

I have long said that if Republicans think the FISA order into Carter Page was abusive, then they’re being remiss in their oversight of FISA generally, because whatever abuse happened with Page happens, in far more egregious fashion, on the FISA applications of other people targeted and prosecuted with them.

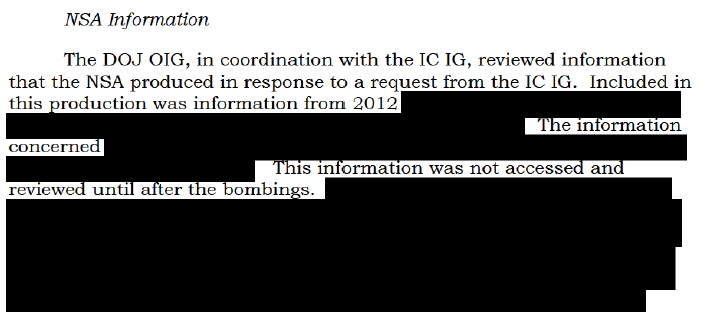

If Michael Horowitz is concerned that the information from paid informants is not properly vetted before being used as the basis for a FISA application, they would be better to focus on any number of terrorism defendants. Adel Daoud appears to have been targeted under FISA based off a referral — probably, like Christopher Steele, a paid consultant — claiming he said something in a forum that the government later stopped claiming; Daoud remains in prison right now after having been set up in an FBI sting.

If Michael Horowitz is concerned that the FBI is misusing press reports in FISA applications, they would be better to focus on the case against Keith Gartenlaub. The FBI based its FISA applications partly off a Wired article that was totally unrelated to anything Gartenlaub was involved with. Gartenlaub will forever be branded as a sex criminal because, after finding no evidence that he was a spy, the government found 10 year old child porn they had no evidence he had ever accessed.

If Michael Horowitz is concerned that information underlying a FISA application included errors — such as that there are no Russian consulates in Miami — he should probably review how Xiaoxing Xi got targeted under FISA because the FBI didn’t understand what normal scholarship about semiconductors involves. While DOJ dropped its prosecution of Xi once it became clear how badly they had screwed up, he was charged and arrested.

And if Michael Horowitz is concerned about FISA abuse, then he should examine why zero defendants have ever gotten able to review their applications, even though that was the intent of Congress. Both Daoud and Gartenlaub should have been able to review their files, but both were denied at the appellate level.

The point being, the eventual report on “FISA abuse” will not be about FISA abuse. It will, once again, be about the President’s grievances. It will, at least according to public reporting, not treat far more significant problems, including cases where the injury against the targets was far greater than it was for Carter Page.

I don’t believe Michael Horowitz believes he is serving as an instrument of the President’s grievances. But by scoping his work to include only the evidence that stems from the President’s grievances and leaving out matters that involve ongoing harm, that’s what he is doing.

Note: I have or had a legal relationship with attorneys involved in these cases, though not when writing the underlying posts.