Freedom And Inequality: Introduction and Index

Posts in this series:

Freedom and Inequality: Introduction and Index

Freedom and Inequality: Freedom From Domination Part I

Freedom and Equality: Freedom From Domination Part 2

Freedom and Equality: Relational Equality Against Social Hierarchies

Freedom And Equality: More On Equality.

Freedom and Equality: Anderson Against Libertarianism

Freedom And Equality: In The Workplace

A Primer On Pragmatism: Method

A Primer on Pragmatism: Truth

A Primer On Pragmatism: Applications

Egalitarianism And Markets

Private Government By Corporations

Inequality And Freedom

Inequality In Social Relations

Introduction

This will be a series of discussions of freedom and inequality, based on works by Elizabeth Anderson, Chair of the Philosophy Department at the University of Michigan. I first heard about Anderson in this New Yorker article by Nathan Heller. Anderson explores the meaning of freedom and equality, especially in the context of work, the economy and the politics of both. Until recently, the dominant ideas were those of conservatives and libertarians, people like Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, and neoliberals of both parties.

The New Yorker article says that historically everyone thought that freedom and equality are at odds: exercise of freedom would naturally lead to increasing inequality. Political domination is a natural consequence of increasing inequality. If that is true, how can democracy survive? Anderson questions the view that freedom and equality are in conflict. The relevance of this idea to our current political environment is obvious. Republicans champion inequality as an exercise of freedom, and neoliberal democrats agree, but argue that some restraints on freedom must exist to prevent too much inequality. We need a new structure to step outside this duality and protect our democracy.

Again historically, people thought of freedom in two ways: negative freedom, that is, freedom from interference, and positive freedom, the range of options available to people. Anderson adds a third idea, freedom from domination. As we saw in the series on Ellen Meiksins Wood, one major Marxist criticism of capitalism is domination of the worker by the capitalist, aided by the state.* We saw in Pierre Bourdieu a detailed study of the way dominance is embedded in social relations.** We have also seen Michel Foucault’s view of power, an idea closely related to domination. I’ll discuss the concept of freedom from domination in this series.

From the New Yorker article:

As the students listened, [Anderson] sketched out the entry-level idea that one basic way to expand equality is by expanding the range of valued fields within a society. Unlike a hardscrabble peasant community of yore in which the only skill that anyone cared about might be agricultural prowess, a society with many valued arenas lets individuals who are good at art or storytelling or sports or making people laugh receive a bit of love.

I’m particularly fond of this idea. I made a living practicing law, and on the side, I did a lot of chorus singing, mostly classical and opera. I made room in my life for voice lessons and the unending rehearsals and performances that dominate the life of the singer. I used to say that among lawyers I was one of the best singers, which seems to me to be what this quote is saying.

The New Yorker article says that one of the major influences for Anderson is pragmatism, the distinctly American philosophy, generated by Charles Peirce, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and William James. It’s leading exponent in the 20th Century was John Dewey.*** A central idea of pragmatism is the definition of “truth”:

To a pragmatist, “truth” is an instrumental and contingent state; a claim is true for now if, by all tests, it works for now.

Ideas are tools, and the truth value of a tool is related to its usefulness. This description of truth throws off centuries of effort to find a fixed point of certainty in the world. It opens the possibility of finding our way through social and individual problems not by reference to some prior version of the truth, but by our own best understandings of our own social reality. I do not currently plan on a formal discussion of this description of truth, and will content myself with pointing it out in passing. But I share that view, and I think it is apparent in much of my thinking and writing.

Reading philosophy papers is difficult for a lay reader like me. Most are presented as arguments with one or more other philosophers. This is not necessarily a good way for a layman to get a positive statement of the views of the author, especially when there are many papers and many arguments. The New Yorker article seems to be a good introduction to the themes Anderson addresses.

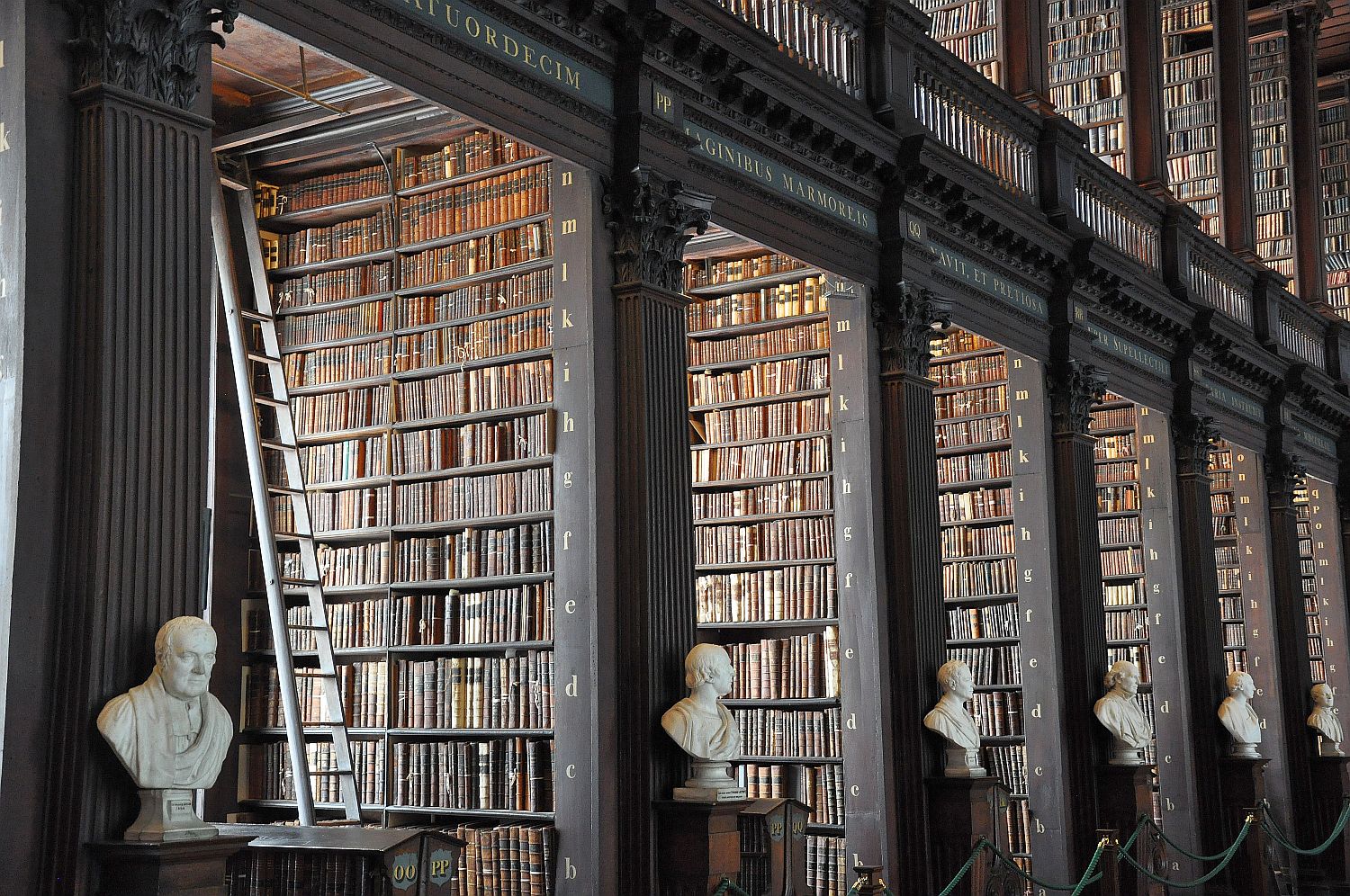

Finding these academic papers online is harder than finding the books I’ve been writing about. I am fortunate to have access to a university’s online library, and I can’t find all of Anderson’s work there; I have no idea if readers can find the material I’m reading through their own public libraries, though I hope so. I’ll be giving the best links I can find, for what that’s worth. And as always, I’ll try to separate Anderson’s thinking and that of the authors she discusses separate from my own views.

I’ll update this post with links to all the posts in this series. Thanks for reading.

======

* Here’s an example. The index to these posts is here.

** See for example this post.

*** Lewis Menand’s The Metaphysical Club is an engaging account of the first three and their friends. Here’s a good introduction to the thought of John Dewey. Richard Rorty considered himself an heir to Dewey. For a fascinating discussion of the nature of truth in pragmatist thought, see Philosophy and Social Hope by Richard Rorty, Ch. 2. It’s worth the effort.

Brief Description of the conclusion of Chapter 2 and Chapters 3-7 of Elizabeth Anderson’s Private Government

Chapter 2 of Elizabeth Anderson’s Private Government ends with several plausible ways of dealing with the lack of freedom and equality* in the workplace. These are:

1. Exit: the employee can quit and find other work.

2. The Rule of Law: we could have a statutory scheme favorable to the freedom of working people.

3. Substantial “constitutional” rights: we could force corporate structures to allow greater worker freedom.

4. Voice: workers could be given greater rights to participate is making decisions about working conditions, as through unions or board positions, modeled by German codetermination in the form of board seats and Worker Councils.

The next four chapters are brief responses to Anderson’s argument. Ann Hughes offers deeper discussion of the history of dissenters such as the Levellers, which was helpful in understanding some of the history David Bromwich discusses the evolution of business away from the egalitarian ideals of the dissidents. Niko Kolodny suggests that being bossed around isn’t that big a deal. Tyler Cowan represents the neoliberal view, that loss of freedom in Anderson’s sense has to be balanced against the gains, and besides, businesses won’t abuse workers much. Anderson deals with the replies in Chapter 7.

I think the comments are interesting, but somehow less than satisfying. Anderson is talking about concepts of freedom and equality that are foreign to most of us. The reply of Tyler Cowan seems utterly unaware that freedom and equality are social goods, valuable in themselves for human flourishing. These benefits are simply irrelevant to economic efficiency, the traditional goal driving libertarian econmics. Kolodny is sympathetic to Anderson’s egalitarianism, but does not recognize these benefits either. Bromwich takes a more philosophical approach founded on Polanyi’s view that labor, money and land are fictitious commodities. But he offers little in the way of an alternative treatment of the turn away from egalitarianism on the left, and nothing suggesting what can be done.

Anderson’s replies are helpful, but she does not return to the fundamental definitions of freedom and equality. She simply takes the replies on their own terms and responds in the same terms. That is disappointing. I’ll offer my own thoughts in this series.

Additional Resources

1. Achieving Our Country by Richard Rorty. Anderson identifies as a pragmatist, and so does Rorty. He is controversial on a number of grounds, but I have learned a great deal from this and other works by Rorty. This is a short book, not theoretical and easy to read. It is an impassioned defense of small-d democracy as described by John Dewey and Walt Whitman. It counsels against despair of that ironic spectator variety of leftism, and argues for an agressive hopeful politics of the left.

2. Podcasts of the Partially Examined Life. This is a philosophy discussion group of some guys who planned to make a living at philosophy but thought better of it, as they say in their introduction. There are two that I think are of interest here. First there is a three part series including an interview with Elizabeth Anderson, Episode 199. There are several episodes devoted to Richard Rorty, listed here. I have listened to the first episode on Achieving our Country, Episode 157, and plan to listen to the rest.

3. In the posts on equality Anderson lays out egalitarian arguments against social hierarchies. For a counterpoint, Episode 157 of the podcast Partially Examined life discusses the Analects of Confucius. The second part is an effort to understand the justification for Chinese hierarchy. Confucius and his school are still influential in China today,and the discussion is a nice counterpoint to the very American ideas of Anderson and the pragmatists.

4. Elizabeth Andersonn wrote a book applying some of her ideas to the world of work. Private Government. Here’s a review in The New Yorker.

5. The Partially Examined Life discusses Peirce and James on Pragmatism in episodes 20 and 22. I have listened to the free part of Episode 20 and plan to listen to the rest.