On January 9, 2014, the government appealed Judge Richard Leon’s decision finding the phone dragnet in Klayman v. Obama to the DC Circuit.

The DC Circuit, of course, is the court that issued US. v Maynard in 2010, the first big court decision backing a mosaic theory of the Fourth Amendment. And while the panel that ultimately heard the Klayman appeal included two judges who voted to have the entire circuit review Maynard, the circuit precedent in Maynard includes the following statement.

As with the “mosaic theory” often invoked by the Government in cases involving national security information, “What may seem trivial to the uninformed, may appear of great moment to one who has a broad view of the scene.” CIA v. Sims, 471 U.S. 159, 178 (1985) (internal quotation marks deleted); see J. Roderick MacArthur Found. v. F.B.I., 102 F.3d 600, 604 (D.C. Cir. 1996). Prolonged surveillance reveals types of information not revealed by short-term surveillance, such as what a person does repeatedly, what he does not do, and what he does ensemble. These types of information can each reveal more about a person than does any individual trip viewed in isolation. Repeated visits to a church, a gym, a bar, or a bookie tell a story not told by any single visit, as does one‘s not visiting any of these places over the course of a month. The sequence of a person‘s movements can reveal still more; a single trip to a gynecologist‘s office tells little about a woman, but that trip followed a few weeks later by a visit to a baby supply store tells a different story.* A person who knows all of another‘s travels can deduce whether he is a weekly church goer, a heavy drinker, a regular at the gym, an unfaithful husband, an outpatient receiving medical treatment, an associate of particular individuals or political groups — and not just one such fact about a person, but all such facts.

With that precedent, the DC Circuit is a particularly dangerous court for the Administration to review a dragnet that aspires to collect all Americans’ call records and hold them for 5 years.

On March 31, 2014, the government submitted a motion for summary judgment in EFF’s FOIA for Section 215 documents with an equivalent to the ACLU. One of the only things the government specifically withheld — on the grounds that it described a dragnet analysis technique it was still using — was an August 20, 2008 FISC opinion authorizing the technique in question, which it did not name.

Two days before FISC issued that August 20, 2008 opinion, the NSA was explaining to the court how it made correlations between identifiers to contact chain on all those identifiers. Two days is about what we’ve seen for final applications before the FISC rules on issues, to the extent we’ve seen dates, suggesting the opinion is likely about correlations.

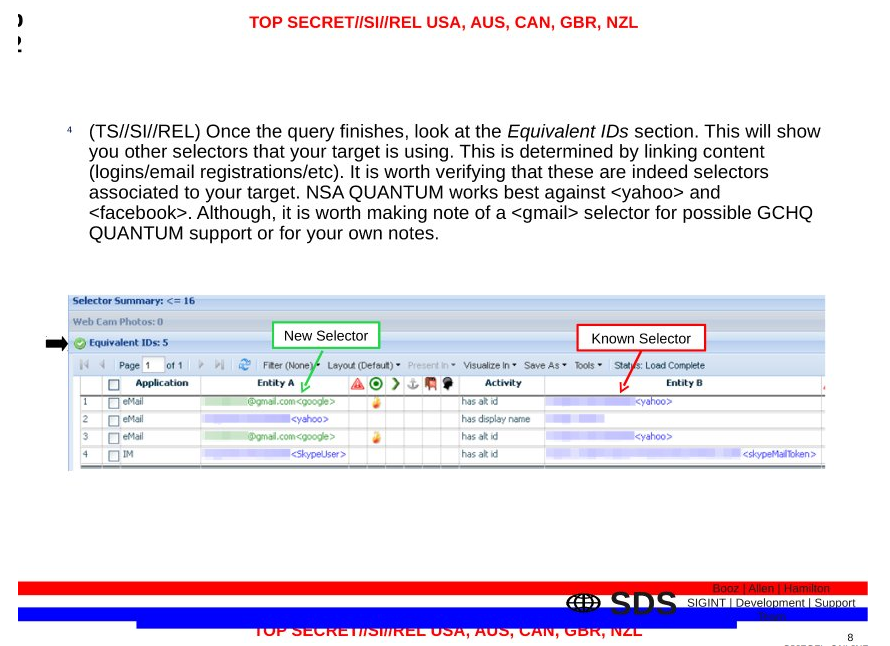

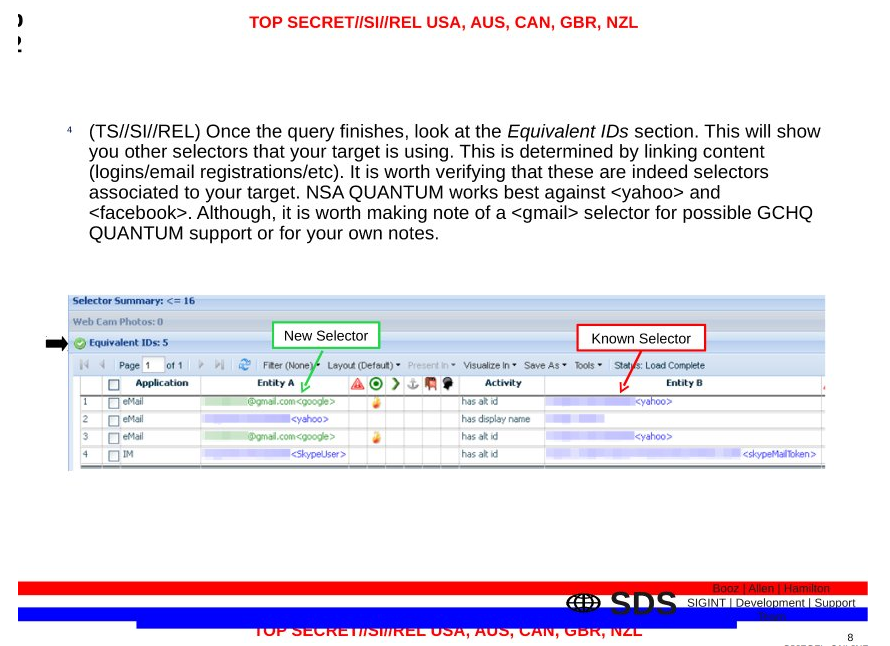

Here’s how the government described correlations, in various documents submitted to the court in 2009.

They define what a correlated address is (and note, this passage, as well as other passages, do not limit correlations to telephone metadata — indeed, the use of “address” suggests correlations include Internet identifiers).

The analysis of SIGINT relies on many techniques to more fully understand the data. One technique commonly used is correlated selectors. A communications address, or selector, is considered correlated with other communications addresses when each additional address is shown to identify the same communicant as the original address.

They describe how the NSA establishes correlations via many means, but primarily through one particular database.

NSA obtained [redacted] correlations from a variety of sources to include Intelligence Community reporting, but the tool that the analysts authorized to query the BR FISA metadata primarily used to make correlations is called [redacted].

[redacted] — a database that holds correlations [redacted] between identifiers of interest, to include results from [redacted] was the primary means by which [redacted] correlated identifiers were used to query the BR FISA metadata.

They make clear that NSA treated all correlated identifiers as RAS approved so long as one identifier from that user was RAS approved.

In other words, if there: was a successful RAS determination made on any one of the selectors in the correlation, all were considered .AS-a. ,)roved for purposes of the query because they were all associated with the same [redacted] account

And they reveal that until February 6, 2009, this tool provided “automated correlation results to BR FISA-authorized analysts.” While the practice was shut down in February 2009, the filings make clear NSA intended to get the automated correlation functions working again,

While it’s unclear whether this screen capture describes the specific database named behind the redactions in the passages above, it appears to describe an at-least related process of identifying all the equivalent identities for a given target (in this case to conduct a hack, but it can be used for many applications).

If I’m right that the August 20, 2008 memo describes this correlations process, it means one of the things the government decided to withhold from EFF and ACLU (who joined Klayman as amici) after deciding to challenge Leon’s decision in a court with a precedent of recognizing a mosaic theory of the Fourth Amendment was a document that shows the government creates a mosaic of all these dragnets.

It’s not just a phone dragnet (and it’s not just US collected phone records). It’s a domestic and internationally-collected phone and Internet and other metadata dragnet, and after that point, if it sucks you into that dragnet, it’s a financial record and other communications dragnet as well (for foreigners, I imagine, you get sucked in first, without an interim stage).

Even though both Janice Rogers Brown and David Sentelle voted to reconsider the mosaic theory in 2010, Sentelle’s questions seemed to reflect a real concern about it. Unsurprisingly, given that he authored a fairly important opinion in US v Quartavious Davis holding that the government needed a warrant to get stored cell site location data while he was out on loan to the 11th Circuit earlier this year, his questions focused on location.

Sentelle: What information if any is gathered about the physical location of wireless callers, if anything? Cell tower type information.

Thomas Byron: So Judge Sentelle, what is not included. Cell tower information is not included in this metadata and that’s made clear in the FISC orders. The courts have specified that it’s not included.

Note how Byron specified that “cell tower information is not included in this metadata”? Note how he also explains that the FISC has specified that CSLI is not included, without explaining that that’s only been true for 15 months (meaning that there may still be incidentally collected CSLI in the databases). Alternately, if the NSA gets cell location from the FBI’s PRTT program (my well-educated guess is that the FBI’s unexplained dragnet — the data from which it shares with the NSA — is a Stingray program), then that data would get analyzed along with the call records tied to the same phones, though it’s not clear that this location data would be available from the known but dated metadata access, which is known only to include Internet, and EO 12333 and BRFISA phone metadata).

Stephen Williams seemed even more concerned with the Maynard precedent, raising it specifically, and using it to express concern about the government stashing 5 years of phone records.

Williams: Does it make a significant difference that these data are collected for a five year period.

Byron’s response was particularly weak on this point, trying to claim that the government’s 90-day reauthorizations made the 5 years of data that would seem to be clearly unacceptable under Maynard (which found a problem with one week of GPS data) acceptable.

Byron: It’s not clear in the record of this case how much time the telephone companies keep the data but the point is that there’s a 90 day period during which the FISC orders are operative and require the telephone companies to turn over the information from their records to the government for purposes of this program. Now the government may retain it for five years but that’s not the same as asking whether the telephone company must keep it for five years.

Williams: How can we discard the five year period that the government keeps it?

Williams also, later, asked about what kind of identities are involved, which would also go to the heart of the way the government correlates identities (and should warrant questions about whether the government is obtaining Verizon’s supercookie).

Byron expressed incredible (as in, not credible) ignorance about how long the phone companies keep this data; only AT&T keeps its data that long. Meaning the government is hoarding records well beyond what users should have an expectation the third party in question would hoard the data, which ought to eliminate the third party justification by itself.

Janice Rogers Brown mostly seemed to want things to be easy, one bright line that cops could use to determine what they could and could not obtain. Still, she was the only one to raise the other kinds of data the government might obtain.

JRB: Does it matter to whom the record has been conveyed. For instance, medical records? That would be a third party’s record but could you draw the same line.

Byron: Judge Brown, I’m glad you mentioned this because it’s really important to recognize in the context of medical records just as in the context, by the way, of telephone records, wiretap provisions, etcetera, Congress has acted to protect privacy in all of these areas. For example, following the Miller case, Congress passed a statute governing the secrecy of bank records. Following the Smith case, Congress passed a statute governing wiretaps. HIPAA, in your example, Judge Brown, would govern the restrictions, would impose restrictions on the proper use of medical information. So too here, FISA imposes requirements that are then enforced by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. And those protections are essential to understanding the program and the very limited intrusion on any privacy interest.

While Byron had a number of very misleading answers, this probably aggravated me the most. After all, the protections that Congress created after the Miller case and the Smith case were secretly overridden by the FISC in 2008 and 2010, when it said limitations under FISA extended for NSLs could also be extended for 215 orders. And we have every reason the government could, if not has, obtained medical records if not actual DNA using a Section 215 order; I believe both would fall under a national security exception to HIPAA. Thus, whatever minimization procedures FISC might impose, it has, at the same time blown off precisely the guidelines imposed by Congress.

The point is, all three judges seemed to be thinking — to a greater or lesser extent — of this in light of the Maynard precedent, Williams particularly so. And yet because the government hid the most important useful evidence about how they use correlations (though admittedly the plaintiffs could have submitted the correlations data, especially in this circuit), the legal implications of this dragnet being tied to other phone and Internet dragnets and from there more generalized dragnets never got discussed.

Don’t get me wrong. Larry Klayman likely doomed this appeal in any case. On top of being overly dramatic (which I think the judges would have tolerated), he misstated at least two things. For example, he claimed violations reported at the NSA generally happened in this program alone. He didn’t need to do that. He could have noted that 3,000 people were dragnetted in 2009 without the legally required First Amendment review. He could have noted 3,000 files of phone dragnet data were not destroyed in timely fashion, apparently because techs were using the real data on a research server. The evidence to show this program has been — in the past at least — violative even of the FISC’s minimization requirements is available.

Klayman also claimed the government was collecting location data. He got caught, like a badly prepared school child, scrambling for the reference to location in Ed Felten’s declaration, which talked about trunk location rather than CSLI.

In substantive form, I don’t think those were worse than Byron’s bad evasions … just more painful.

All that said, all these judges — Williams in particular — seemed to want to think of this in terms of how it fit in a mosaic. On that basis, the phone dragnet should be even more unsustainable than it already is. And some of that evidence is in the public record, and should have been submitted into the record here.

Still, what may be the most important part of the record was probably withheld, by DOJ, after DOJ decided it was going to appeal in a circuit where that information would have been centrally important.