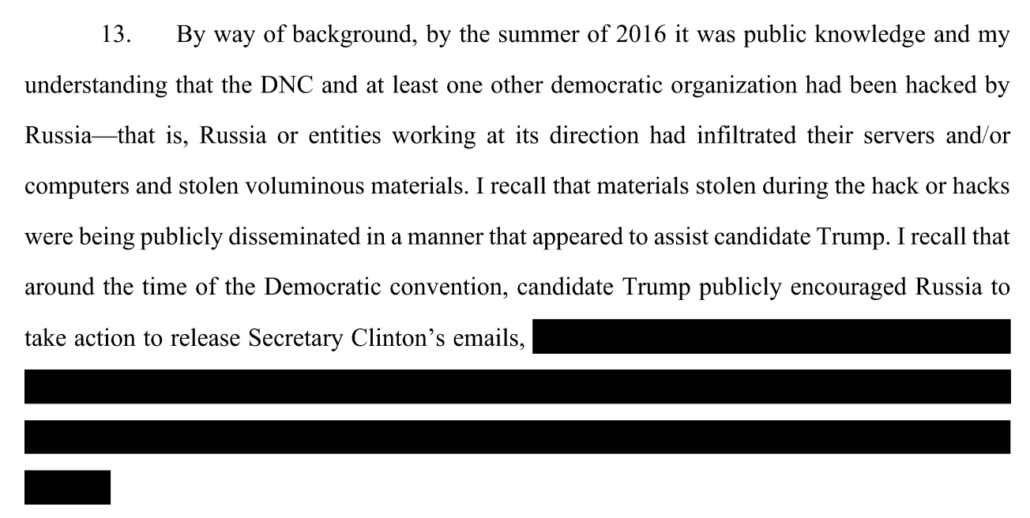

The frothy right is in a tizzy again.

Judicial Watch got a FOIA response that the frothers are reading out of context — without even reading the existing public record much less asking the question they now claim to want to answer — and claiming that Mueller’s attorneys kept wiping their phones.

The FOIA was for records pertaining to Lisa Page and Peter Strzok’s use of DOJ-issued mobile phones while assigned to Mueller’s team. The FOIA was not for a description of the record-keeping in the Mueller office. The FOIA was not for a final accounting of every text that every Mueller team member sent while working for Mueller. If a document mentions Page or Strzok’s phones, it is included here; if it does not, it was withheld.

That said, the frothy right is largely ignoring what the documents show, and instead referring to a single tracking sheet in isolation from the rest, to conclude that multiple Mueller officials wiped their own phones.

To understand what the documents show, it’s best to separate it into what the documents show about Page and Strzok, and then what they show about everyone else.

Mueller’s Office discovered too late that Page and Strzok’s phones had been reset according to standard procedure

The documents show, first of all, that the available paper trail backs the explanations around what happened to Page and Strzok’s Mueller iPhones, which both used for less than 3 months in 2017 while they also used (and sent damning texts on) their FBI issue Samsung phones.

The documents show that Lisa Page was among the first people assigned a Mueller iPhone. Justice Management Department’s Christopher Greer asked for iPhones specifically to deploy a standard mobile technology (though a later document reflects Adam Jed appears to have gotten an Android). Then, after a 45-day assignment, Page left. As the first person to leave the team, she left before processes were put into place to document all that; Page is actually the one who initiated the bureaucratic process of leaving. “Since we have our first detail employee leaving us, it is time to roll out our first form/policy,” Mueller’s administrative officer explained. Mueller’s Records Officer noted she didn’t have to be at the meeting, but provided an Exit Checklist to use on Page’s out-processing. The Records Officer further directed, weeks before anyone discovered Page’s damning texts with Strzok,

Please make sure [Page] doesn’t delete any text messages off her DOJ iPhone, if any.

Everything else should be saved on her H drive on JCON and in her email. This will be good for me as the RSO to go behind and see how that function works.

Mueller’s Administrative Officer also couldn’t make the meeting. But he noted that Page had a laptop “which may already been in [redacted] area, a DOJ cell phone & charger” and noted that “All equipment that I need will be covered as you go through the form.”

The FOIAed documents don’t reveal this, but a DOJ IG Report released in December 2018 reveal that Page left her devices on a shelf in the office she was using.

The SCO Executive Officer completed Page’s Exit Clearance Certification, but said that she did not physically receive Page’s issued iPhone and laptop. During a phone call, Page indicated to SCO that she had left her assigned cell phone and laptop on a bookshelf at the office on her final day there.

On July 17, two days after she left, that Administrative Officer confirmed that, “I have her phone and laptop.”

That is, everyone involved was trying to do it right, but Page was the first person put through this process so everyone admitted they were instituting procedures as they went.

Out-processing of Peter Strzok in August, in the wake of the discovery of Strzok’s texts with Page, was a good deal more terse. That said, the Records Officer did review his phone for anything that had to be saved on September 6, 2017, and found nothing of interest.

Still, their Exit Forms show both returned their iPhone. (Strzok; Page)

It’s only in January 2018, as DOJ IG started to look into their texts, that Mueller’s office discovered they couldn’t account for Page’s iPhone. JMD ultimately found it, but not until September 2018. The phone showed that it had been reset to factory settings, which was standard DOJ policy, on July 31, 2017, two weeks after Page turned it over and left SCO.

In fall 2018 and again in January 2019, numerous people at DOJ tried to find alternative ways to reconstruct any texts Page and Strzok sent on their Mueller iPhones. Because the effort started over a year after they had stopped using the phones, neither DOJ nor Verizon had even log files from the texts anymore. So a DOJ official reviewed Strzok’s phone and found nothing, may not have reviewed Page’s phone, but nevertheless found no evidence Page tried to evade review.

That is, for the subject Judicial Watch was pursuing, the FOIA was a bust.

In response to the Page-Strzok scandal, Mueller appears to have adopted a standard higher than DOJ generally

The Page-Strzok files also suggest certain things about what Mueller did as his investigation was roiled by claims focusing on the two former FBIers.

- It appears that, after the shit started hitting the fan, Mueller engaged in record-keeping above-and-beyond that required by DOJ guidelines (that’s what the frothers are complaining about)

- When things started hitting the fan, Mueller’s Chief of Staff Aaron Zebley seems to have started taking a very active role in the response

- FBI continued to issue Page and Strzok updated phones even while they had Mueller iPhones, which is probably the case for at least the FBI employees on Mueller’s team, making confusion about phones more likely

- Both DOJ and Verizon would have some ability to reconstruct any texts for phones with problems identified in real time, as opposed to the year it took with Page and Strzok

Here’s the standard DOJ adopts with regards to the use of texts on DOJ-issued phones. DOJ guidelines for retaining texts all stem from discovery obligations — and DOJ, unlike FBI, puts the onus on the user to retain texts.

The OIG reviewed DOJ Policy Statement 0801.04, approved September 21, 2016, which establishes DOJ retention policy for email and other types of electronic messaging, to include text messages. Policy 0801.04 states that electronic messages related to criminal or civil investigations sent or received by DOJ employees engaged in those investigations must be retained in accordance with the retention requirements applicable to the investigation and component specific policies on retention of those messages.

OIG also reviewed DOJ Instruction 0801.04.02, approved November 22, 2016, which provides guidance and best practices on component use of electronic messaging tools and applications for component business purposes.

Section C of 0801.04.02 (Recordkeeping Guidance for Electronic Messaging Tools in Use in the DOJ) subsection 9 (Text Messaging), states that text messaging may be used by staff only if it has been approved by the Head of the Component and in the manner specifically permitted by written component policies. Additional guidance was provided in a memo from the Deputy Attorney General dated March 30, 20 I I, titled ‘Guidance on the Use, Preservation, and Disclosure of Electronic Communications in Federal Criminal Cases.’ The memo states that electronic communications should be preserved if they are deemed substantive. Substantive communications include:

-

- Factual information about investigative activity

- Factual information obtained during interviews or interactions with witnesses (including victims), potential witnesses, experts, informants, or cooperators

- Factual discussions related to the merits of evidence

- Factual information or opinions relating to the credibility or bias of witnesses, informants and potential witnesses; and

- Other factual information that is potentially discoverable under Brady, Giglio, Rule 16 or Rule 26.2 (Jencks Act).

So people using DOJ phones are only required to keep stuff that is case related. DOJ IG had, in 2015, complained about DOJ’s retention of texts, but the standard remained unchanged in 2018.

In January 2018, after someone had leaked news of the Page-Strzok texts to the NYT and after DOJ released their texts to the press (possibly constituting a privacy violation and definitely deviating from the norm of not releasing anything still under investigation by DOJ IG) and after Senator Chuck Grassley and Ron Johnson started making unsubstantiated claims about the texts, Mueller’s Chief of Staff, Aaron Zebley appears to have taken a very active role in the response. That’s when Mueller Executive Officer Beth McGarry Mueller’s Chief of Staff sent Page and Strzok’s Exit Paperwork to Zebley. And that’s when Mueller and DOJ IG discovered no one could find Page’s phone.

Not said in any of these documents, but revealed in the DOJ IG Report, is that Page and Strzok continued to use their FBI Samsung phones, and indeed were issued updated Samsungs after being assigned to Mueller’s team.

Based on OIG’s examination of their FBI mobile devices, Page and Strzok also retained and continued to use their FBI mobile devices. Specifically, on or about May 18, 2017, Page received an FBI-issued Samsung Galaxy S7 mobile device to replace her previously-issued FBI Samsung Galaxy SS. On or about July 5, 2017, Strzok received an FBl-issued Samsung Galaxy S7 mobile device to replace his previously-issued FBI Samsung Galaxy S5.

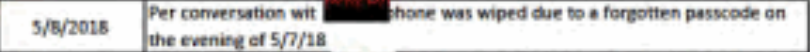

This was already known, because that’s where all their compromising texts were. But among other things, it makes it clear that some Mueller team members (especially the FBI employees, virtually all of whose names are redacted), may also have continued to use their existing FBI issue phone even while using the Mueller iPhone. With the exception of the 70-something year old James Quarles, whose phone “wiped itself without intervention from him” in April 2018 and who did not use text or have any photos on it when it was wiped, the suspicious events Republicans are complaining about came from DOJ employees, who might be most likely to juggle multiple phones and passwords.

Finally, one more detail of note in the Page and Strzok documents pertains to the other revelations. As noted, as part of the effort to find any texts they might have sent, DOJ reached out to Verizon, to try to figure out what kind of text traffic had been on their phones. Verizon responded that it only keeps texting metadata for 365 days, with rolling age-off, so it couldn’t help (in fall 2018 and January 2019) to access what Page and Strzok had done with their phones in summer 2017. As part of that discussion, however, JMD’s Greer noted that “our airwatch logs may only go back 1 year.” Airwatch is the portal via which corporate users of iPhones track the usage of their employees. It means that so long as something happens with a phone within a year, some data should be available on Airwatch. That is to say, DOJ had two means by which to reconstruct the content of a phone with a problem discovered in real time, means not available given the delay in looking for Page and Strzok’s phones.

The log of phone reviews covering all Mueller personnel

Ultimately, Judicial Watch’s FOIA showed that the documents they were after — the paper trail on the Page and Strzok phones — backs up what has always been claimed about the phones. They were treated via routine process, but as a result there were no texts to review when DOJ IG got around to review them.

So they instead made a stink about just four pages in the release, what appears to be a log — probably started in January 2018, as the Page and Strzok issues continued to roil — of every instance where a Mueller staff phone got reviewed.

The log starts with Page, Strzok, and two other people whose identities are redacted. It has an additional number of entries interspersed with ones from January 2018 which may be those out-processed under DOJ’s normal terms, prior to the initiation of this log. After that, though, the log seems to show meticulous record-keeping both as people were out-processed and any time something went haywire with a phone.

Here, for example, is the entry showing that Kevin Clinesmith’s phone was reviewed on March 5, 2018, and two texts and three photos that were not required to be kept as a DOJ record were emailed to him.

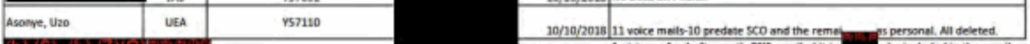

Here, for example, is a record showing that the phone of Uzo Asonye, a local prosecutor added to Manafort’s tax cheat trial in EDVA, got cleared of ten voice mails that pre-dated his involvement with the Mueller team when he was out-processed from the Mueller team.

In other words, Mueller’s team made sure phones were clean, even if they hadn’t been when the came into the team.

Some of what the frothers are pointing to as suspicious is someone wiping their phone when they get it — good security practice and, since the phone is new to them, nothing that will endanger records.

In others of the instances the frothers are complaining about, the log shows that someone immediately alerted record-keepers when they wiped their phone, which (if there were a concern) would provide DOJ an opportunity to check Airwatch.

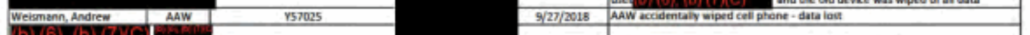

One thing Republicans are focusing most closely on is that Andrew Weissmann twice “accidentally” wiped his phone, having done so on March 8 and September 27, 2018.

Note, both these instances involve the same phone, and also the same phone he had in what appears to be the final inventory. So while this is not entirely above suspicion, it’s not the case that Weissmann kept wiping phones before DOJ had a chance to check what he had on there before he got a new one. Rather, it appears he wiped the same phone twice and told the record-keepers about it in real time. Moreover, the wipes do not correlate to one possible damning explanation of them, that Weissmann was trying to cover up leaks to the press that Manafort would later accuse him and the Mueller team generally of.

There appears to have been nothing unusual about Weissmann’s out-processing review in March 2019.

So when DOJ had a chance to look at how Weissmann had used his phone for the last six months he used a Mueller phone, it found nothing.

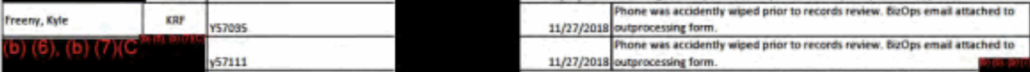

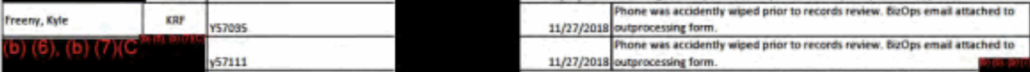

Another of the things Republicans find particularly suspicious is that the phones of Kyle Freeny and Rush Atkinson were both wiped within days of each other (Freeny is a woman, which some of the self-described experts on the Mueller investigation got wrong in their stories on this). For Freeny and one other person (likely an FBI agent), this appears to have been an out-processing review.

Note that here and in many other cases, the description uses the passive voice. “Was [accidentally] wiped,” with no subject identified. There’s good reason to believe — based on the Records Officer retroactive descriptions about Strzok’s phone, the occasional use of the first person, and multiple references to the Administrative Officer — that these are written from the voice of the Records Officer, not the lawyer or agent in question. That is, many of the incidences of descriptions that a phone “was wiped” in no way suggest the person used the phone wiped it. Rather, it seems to be the Records Officer or someone else in the review process. And for a number of those instances there’s a clear explanation why the phone was wiped, which would be normal process for most DOJ transitions in any case.

It does appear Atkinson’s phone was wiped just days after Freeny’s phone, though it was identified in plenty of time to obtain the metadata, if needed.

But like Weissmann, Atkinson’s out-processing review (curiously, the very last one from the entire Mueller team) showed nothing unusual.

In short, what the frothy right appears to have worked themselves up about is that after the conduct of Page and Strzok raised concerns, Mueller imposed record-keeping that DOJ would not otherwise have done, record-keeping that attempted (even though it is not required by DOJ policy) to track every single personal text sent on those phones. And for many of the instances that frothers look at with suspicion, they’re actually seeing, instead, a normal DOJ treatment of a phone.

Timeline

May 20, 2017: Add four accounts, give them iPhones, including Lisa Page and Brandon Van Grack.

May 31, 2017: Page and Strzok first logged into SCO laptops.

June 15, 2017: What kind of tracking do we need for phones? Answer: IMEI. [Includes non-exempt team through that date.]

July 13, 2017: Out-processing of Lisa Page, for whom the process was invented. [Includes list of admin personnel.]

July 17, 2017: Page had handed over her devices, SCO still working with JMD to figure out how to back up common drive.

July 27, 2017: Michael Horowitz tells Mueller of Page-Strzok texts he discovered.

July 31, 2017: Page phone reset to factory settings.

August 9, 2017: Strzok sends exit checklists.

August 10, 2017: Strzok separates from office.

September 6, 2017: Records Officer reviews Strzok’s phone.

November 30, 2017: Mike Flynn informed of Strzok’s texts.

December 2, 2017: NYT reports on Strzok’s texts.

December 13, 2017: DOJ releases first batch of Page-Strzok texts, while trying to hide they were the source.

January 19, 2018: Stephen Boyd informs Chuck Grassley of archiving problems.

January 22, 2018: Strzok’s Mueller iPhone located.

January 23, 2018: Attempt to get texts from Verizon, but both content and metadata no longer stored.

January 25, 2018: Beth McGarry sends Aaron Zebley exit forms from Strzok and Page.

January 26, 2018: LFW notes that they’ve lost Page’s phone, but hands the search off to JMD. Greer notes, specifically, however, that “SCO policy was to reuse them and not hold.”

Late January 2018: FBI Inspection Division finds FBI Samsung phones, provide to DOJ IG.

February 8, 2018: Trump supporter Cesar Sayoc starts plotting attack on Strzok and others.

March 5, 2018: Kevin Clinesmith’s out-processing shows nothing unusual.

March 8, 2018: Andrew Weissmann wipes his phone.

May 4, 2018: Page resigns from FBI.

June 2018: DOJ IG discovers more texts, changes conclusion of Midyear Exam report.

June 14, 2018: Release of Midyear Exam report.

August 10, 2018: Strzok fired from FBI.

Early September 2018: Justice Management Division finds Page’s Mueller iPhone, provides to DOJ IG.

September 13, 2018: SCO Records Officer contacts DOJ IG about what status they got Page’s phone in.

September 21, 2018: Draft language between records officer and Aaron Zebley for DOJ IG Report. Also an attempt to check Airwatch for backups to the phones, but they only go back one year.

September 27, 2018: Andrew Weissmann wipes his phone.

October 17, 2018: DOJ IG informs SCO Records Officer that they have the phone, but that it had been reset to factory settings.

October 22, 2018: DOJ IG Cyber Agent follows up about DOJ IG Report language.

November 15, 2018: FBI Data Collection tool not archiving texts reliably.

November 27, 2018: Kyle Freeny’s phone wiped as part of out-processing.

November 29, 2018: Rush Atkinson’s phone accidentally wiped.

Late December 2018: DOJ IG releases report on archiving of DOJ phones.

December 27, 2018: Zebley responds to Rudy Giuliani claim about destruction of evidence.

January 18, 2019: JMD asks Verizon for texting data for Page and Strzok’s phones, but Verizon’s metadata records only go back 365 days.

January 30-31, 2019: LFW asks to cancel Strzok’s phone.

March 28, 2019: Andrew Weissmann’s out-processing review shows nothing unusual.

June 11, 2019: Rush Atkinson’s out-processing review shows nothing unusual.

December 9, 2019: DOJ IG releases Carter Page IG Report.

Unclear date: Inventory of all phones.