Who Will Redact Our Next Big Constitutional Debate?

In her Gitmo anniversary piece, Dahlia Lithwick, piggybacking on Adam Liptak’s earlier report, used the extensive redactions in the DC Circuit Opinion overturning Adnan Latif’s habeas petition to illustrate how little the courts are telling us about his fate, our detention program, and its impact on the most basic right in this country, habeas corpus.

In her Gitmo anniversary piece, Dahlia Lithwick, piggybacking on Adam Liptak’s earlier report, used the extensive redactions in the DC Circuit Opinion overturning Adnan Latif’s habeas petition to illustrate how little the courts are telling us about his fate, our detention program, and its impact on the most basic right in this country, habeas corpus.

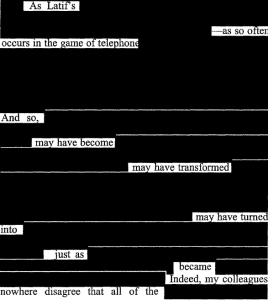

But in the spirit of the day, I urge you to stop for a moment and look at the decision itself, so heavily redacted that page after page is blacked out completely. The court, in evaluating a secret report on Latif, can tell us very little about the report and thus the whole opinion becomes an exercise in advanced Kafka: The dissent, for instance notes that “As this court acknowledges, “the [district] court cited problems with the report itself including [REDACTED]. … And according to the report there is too high a [REDACTED] in the report for it to have resulted from [REDACTED].” Liptak describes all this as an exercise in “Mad Libs, Gitmo Edition.” But in the end, it’s also an exercise in turning the legal process of assessing the claims of these prisoners at Guantanamo Bay into something that replaces one legal black hole with another: pages and pages of black lines that obscure in words what has been obscured in fact. Americans will never know or care what was done at the camp and why if the legal process that might have transparently corrected errors happens behind blacked-out pages.

Latif’s classified petition for cert has just been filed.

We won’t get to see that petition, though, until after the court redacts it, at which point it will presumably look just like the Circuit Opinion–page after page of black lines.

It’s worth asking who will get to redact that petition, which is after all an important effort not only to free a man cleared for release years ago, but also to restore separation of powers and prevent detainees and Americans alike from being held solely on the basis of an inaccurate intelligence report.

That’s important because, thus far, the existing court documents in this case have been redacted inconsistently.

We know that because the dissent in the Circuit Opinion quotes language from Judge Henry Kennedy’s ruling, yet that language doesn’t appear anywhere in the unredacted sections of his ruling itself. For example, David Tatel refers to the “factual errors” Kennedy described (21; PDF 88) and cites Kennedy’s repetition of Latif’s explanation for having lost his passport–he “gave it to Ibrahim [Alawi] to use in arranging his stay at a hospital.” (37; PDF 104) Yet the appearances of these phrases have been entirely redacted from Kennedy’s opinion (there are many more fragments for which the same is true, supporting general claims about the inaccuracy of the report, but they are less specific).

Indeed, the Circuit Opinion itself is internally inconsistent, as Tatel’s citations to Janice Rogers Brown’s admission that the district court “cited problems with the report itself” (23; PDF 93), one of which she agreed was an “obvious mistake” (22; PDF 89) appear unredacted in his dissent, but not in the majority opinion itself (indeed, the citations to it are redacted in Tatel’s opinion).

Further, I would bet that one of the obvious errors in the report described by all these opinions pertains to Latif’s nationality. As I lay out in more detail here, the public Factual Return makes it clear that the government recorded Latif’s nationality as Bangladeshi up until March 6, 2002, a month and a half after he arrived at Gitmo.

Ala’dini’s full ISN is ISN-US9BA-00156 (DP), in which the number 156 is Ala’dini’s unique identifier and the BA designation indicates the nationality that Petitioner for a time had claimed. See ISN 156 Knowledgeability Brief (Feb. 2002); ISN 156 SRI (May 29, 2002) (indicating petitioner repeatedly lied about his country of origin (Bangladesh) and gave a fake name in all past interviews). Petitioner Ala’dini, to be clear, has since claimed that he is a national of Yemen. E.g., ISN 156 ISN 156 SIR (March 6, 2002). [¶7 PDF 8]

Since, as the dissent makes clear, the report on which the government primarily relies was “produced in the fog of war,” it must have been produced before Latif arrived at Gitmo (we have every reason to believe it was an intake document reflecting interrogations from when he was picked up in Pakistan). This in turn means it is likely that the report, like the first Gitmo documents, recorded Latif’s country of origin as Bangladesh. And if it does, it would be shocking for that detail to be unmentioned in the legal discussion, particularly since the majority opinion defines the presumption of regularity to mean “the government official accurately identified the source and accurately summarized his statement.” If the report is an interrogation report of Latif himself, identification of him as Bangladeshi would go right to the heart of the presumption of regularity. Just as importantly, both the majority and the dissent describe problems with the report potentially introduced in the translation and transcription. If the government didn’t even know that Latif was Yemeni, not Bangladeshi, it would be centrally important to translation questions. So the government’s errors about Latif’s nationality would seem to be an issue that goes to the heart of the legal discussion about the accuracy of the report. And yet, while Court Security Officers reviewing the Factual Return didn’t find the government’s misidentification of Latif as Bangladeshi to be classified when they redacted that document, it seems likely similar mentions got redacted in all the opinions.

Is the government hiding behind redactions that they’re holding someone indefinitely based on a report that didn’t even get his nationality right?

Finally, if I’m right that the report in question is TD-314/00684-02, we’ll probably be re-entering the Kafkaesque world in which our government asserts that documents released by WikiLeaks remain “classified.”

When I first wrote about the report, it went from the grey area of publication in WikiLeaks and McClatchy’s databases into the public domain. While Chief Justice John Roberts’ censors might not consider my humble blog part of the public domain, Benjamin Wittes cited from my original post on that CIA cable (and the NYT’s Adam Liptak linked to it). It would be hard to dismiss Wittes’s writing at Lawfare as that of a Dirty Fucking Hippie blogger given that both the majority and dissent opinions in this case cite a paper on evidentiary standards in Gitmo cases by him and Robert Chesney. Mind you, I fully expect that if the report is TD-314/00684-02, the courts will continue to redact its serial number, even though it has repeatedly been referred to in reporting on this case. But that, by itself, would say significant things about the transparency of our constitutional processes.

Whether SCOTUS grants Latif cert or not is an incredibly important legal question (with the codification of indefinite detention in the NDAA, these are issues that affect all Americans). We know that one of the only documents that claims Latif had ties to the Taliban was some kind of intake report tied to the processing of 195 detainees captured by Pakistan. We know our government had Latif in custody for months before they figured out he was Yemeni, not Bangladeshi, and the document they claim justifies his continued detention probably repeats that mistake. We know that there are “factual errors” in the report, one of which even Janice Rogers Brown considers an “obvious mistake.” We know that Latif offered what Henry Kennedy considered a plausible explanation for why he didn’t have his passport when he was picked up, a detail that the government claims tends to implicate him.

All of these details suggest the government has an incredibly shoddy case against Latif.

But the government has hidden the shoddiness of its case behind great black walls of redaction. And, just as damning for the government, the government has also hidden these details behind arbitrary redaction practices that don’t even remain consistent over the same document, much less from court to court.

SCOTUS may well deny Latif cert, in which case a man the government cleared for release will continue to be held indefinitely, perhaps for another decade. But if they’re going to do so, they owe it to the American people to show just how shoddy the case they’re deciding on really is.