DNA Sequence Analysis Shows Ebola Outbreak Naturally Ocurring, Not Engineered Virus

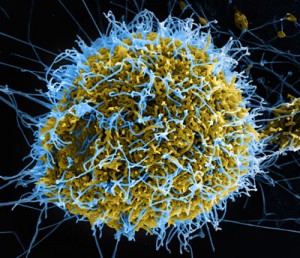

In an electron microscope image that has been colorized, Ebola virus particles in blue are being extruded from an African Green Monkey kidney cell in yellow, grown in a laboratory cell culture system. Photo produced by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

I had really hoped I wasn’t going to have to write this post. Yesterday, Marcy emailed me a link to a Washington’sBlog post that breathlessly asks us “Was Ebola Accidentally Released from a Bioweapons Lab In West Africa?” Sadly, that post relies on an interview with Francis Boyle, whom I admire greatly for his work as a legal scholar on bioweapons. My copy of his book is very well-thumbed. But Boyle and WashingtonsBlog are just wrong here, and it takes only seconds to prove them wrong.

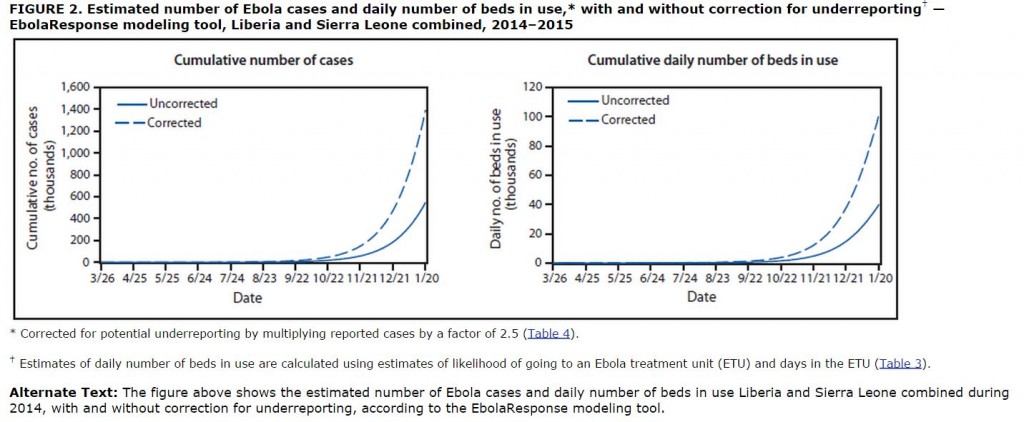

Shortly after getting the email and reading the blog post, I sent out tweets to this summary and this original scientific report which describe work on DNA analysis of Ebola isolated from multiple patients during the current outbreak. That work conclusively shows that the virus in the current outbreak is intimately related to isolates from previous outbreaks with changes only on the order of the naturally occurring mutation rate known for the virus. Further, these random mutations are spread evenly throughout the short run of the virus’s genes and there are clearly no new bits spliced in by a laboratory. Since I wasn’t seeing a lot of traction from the Washington’sBlog post, I was going to let it just sit there.

I should have alerted last night when I heard my wife chuckling over the line “It is difficult to describe working with a horse infected with Ebola”, but I merely laughed along with her and didn’t ask where she read it.

This morning, while perusing the Washington Post, I saw that Joby Warrick has returned to his beat as the new Judy Miller. Along with the line about the Ebola-infected horse, Warrick’s return to beating the drums over bioweapons fear boasts a headline that could have been penned by WashingtonsBlog: “Ebola crisis rekindles concerns about secret research in Russian military labs“.

Warrick opens with a re-telling of a tragic accident in 1996 in a Soviet lab where a technician accidentally infected herself with Ebola. He uses that to fan flames around Soviet work in that era:

The fatal lab accident and a similar one in 2004 offer a rare glimpse into a 35-year history of Soviet and Russian interest in the Ebola virus. The research began amid intense secrecy with an ambitious effort to assess Ebola’s potential as a biological weapon, and it later included attempts to manipulate the virus’s genetic coding, U.S. officials and researchers say. Those efforts ultimately failed as Soviet scientists stumbled against natural barriers that make Ebola poorly suited for biowarfare.

The bioweapons program officially ended in 1991, but Ebola research continued in Defense Ministry laboratories, where it remains largely invisible despite years of appeals by U.S. officials to allow greater transparency. Now, at a time when the world is grappling with an unprecedented Ebola crisis, the wall of secrecy surrounding the labs looms still larger, arms-control experts say, feeding conspiracy theories and raising suspicions.

/snip/

Enhancing the threat is the facilities’ collection of deadly germs, which presumably includes the strains Soviet scientists tried to manipulate to make them hardier, deadlier and more difficult to detect, said Smithson, now a senior fellow with the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, a research institute based in Monterey, Calif.

“We have ample accounts from defectors that these are not just strains from nature, but strains that have been deliberately enhanced,” she said.

Only when we get three paragraphs from the end of the article do we get the most important bit of information to be gleaned from the Soviet work on Ebola:

Ultimately, the effort to concoct a more dangerous form of Ebola appears to have failed. Mutated strains died quickly, and Soviet researchers eventually reached a conclusion shared by many U.S. biodefense experts today: Ebola is a poor candidate for either biological warfare or terrorism, compared with viruses such as smallpox, which is highly infectious, or the hardy, easily dispersible bacteria that causes anthrax.

Note also that, in order to make Ebola more scary, Warrick completely fails to mention the escape of weaponized anthrax from a Soviet facility in 1979, infecting 94 and killing 64, dwarfing the toll from the two Ebola accidents.

And lest we calm down about Ebola and the other bioweapons the Soviets worked on, Warrick leaves us this charming tidbit to end the article: Read more →