[NB: check the byline as usual, thanks. Updates will appear at the bottom of this post. /~Rayne]

There are so many quirks to Russia’s military deployment in its invasion of Ukraine that it’s obvious to non-military observers this has not been an effective mission or missions.

Let’s say you’re the average event planner without any military background who must organize a very large family gathering with many family members in fleets of gas-sucking vehicles. Would you send them out on the road without ensuring there were fueling locations or respite points for water and food?

Would you stage them so that they didn’t overwhelm any system they needed for travel, refueling, and rest?

Would you allow the family to head out on the road with which they may not be familiar, without ensuring a couple different methods of communications?

Would you brief everyone before they left on Plan A, providing a Plan B and C in case there were problems along the way?

This is a hyper simplification of the scenario, but in essence this is what should have been considered long before gathering more than 150,000 troops at the Russian-Ukraine border, before deploying them to invade Ukraine.

These extremely basic issues appear not to have been addressed in any invasion plan.

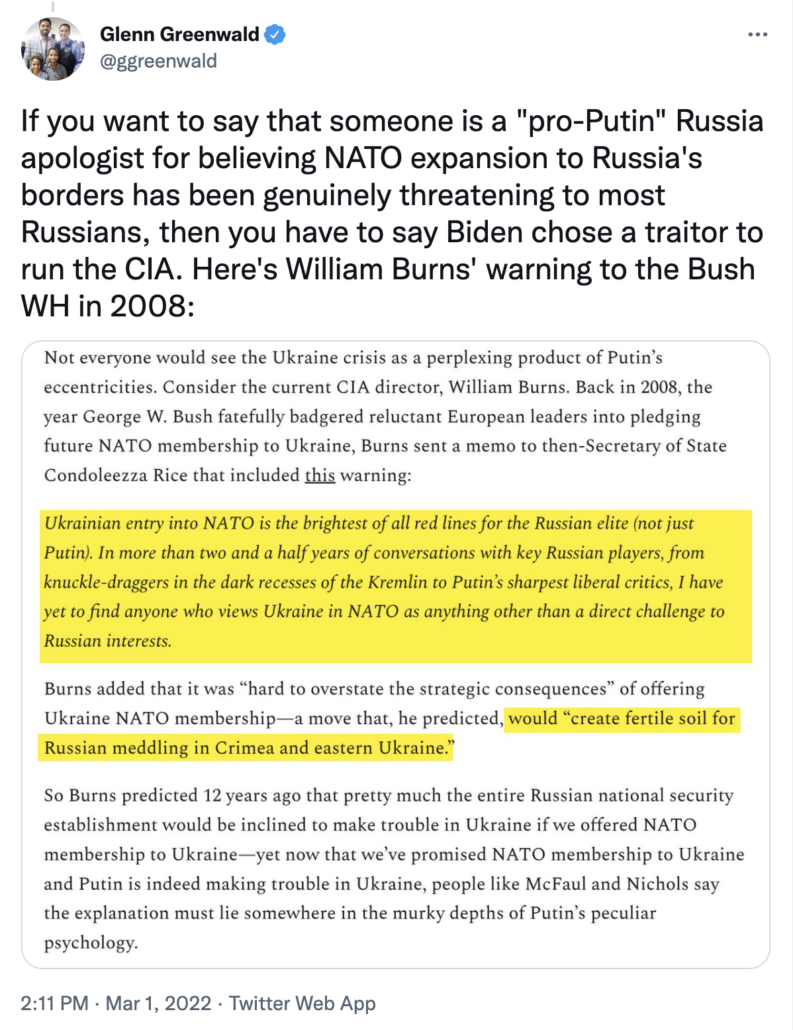

Some of these challenges to Russian troop and equipment deployment have only exacerbated the cognitive dissonance of observers.

Can this really be an invasion by the Russians? Has their military’s vaunted capability been hyperbole, or are we supposed to believe there’s more and better coming? Should other countries scramble to throw troops and materiel at this situation when it’s not at all clear what happened to this initial offensive?

~ ~ ~

On February 27 a few days after the invasion began I retweeted this thread by Kamil Galeev, fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center. I still believe this is a must-read.

The shift inside Russian defense from efficiency-maximization to court politics-maximization is a valuable insight and explains some of what we see — not a top-notch well-equipped ground force but one using off-the-shelf Chinese-made walkie-talkies to communicate insecurely.

Ditto the discussion on land-maxing versus PR-maxing, and by PR-maxing it is meant a tradeoff between land-force investment and naval force (stick a pin in this point for later[1]). Again, this could explain why we see less-than-optimal equipment and troops in the first echelon deployed.

And no obvious signs of a second echelon to follow, let alone a third.

Also extremely important is the perspective on Putin’s reliance on special operations versus a true war strategy — literally employing tactics not strategy. But it’s likely what got Putin elected as president in 2000 by way of covert democidal bombings and kept him in office as he continued to use special operations on Crimea, south Georgian, and eastern Ukraine territory.

Amassing an invasion force of more than 150,000 troops and equipment is not a special operation, just as for an event planner an intimate picnic isn’t a wedding banquet.

Lousy logistics and tactics not strategy appear on the face of it to be Russia’s fundamental problem, with inadequate equipment making things worse.

None of these observations and assessments explain this:

Or this — one of several videos showing Russian tanks and other equipment being towed by Ukrainian tractors.

Perhaps much of this explains the rise of Wagner Group and its service for Russian objectives. It not only provides deniability, but it bypasses the court politics, provides its own better equipment, and it serves Putin’s propensity to use special operations tactics instead of strategy.

~ ~ ~

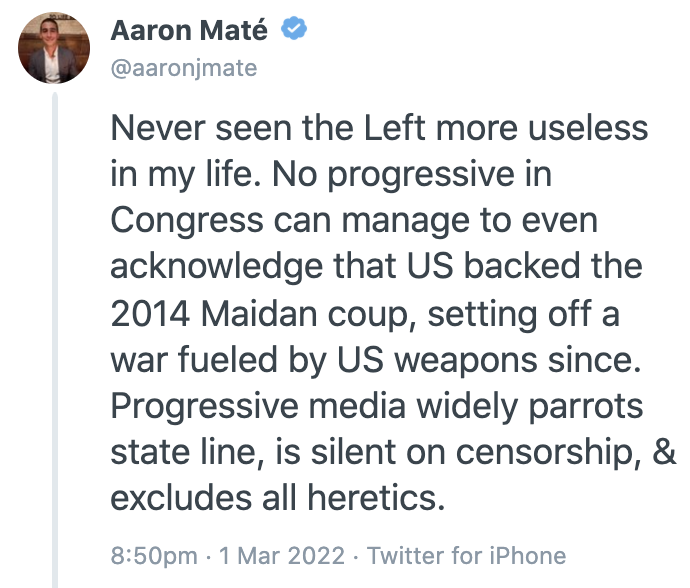

None of the politics and logistics fail, though can explain why Russian national guard units knew about the invasion long before deployed units did — in particular the Chechen National Guard.

Why are Chechens being deployed instead of regular Russian troops? Was this another end run around Russia’s internal politics? (Stick another pin here, too.[2])

This may explain in part why U.S. intelligence has been of high quality — the Chechen security force was sloppy in its operations security and easily monitored.

But the intelligence we’ve seen so far doesn’t explain why the Chechens were needed at all.

A key group of Chechens tasked with a special operation to assassinate Zelenskyy was “eliminated” according to Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council’s Secretary in a live broadcast. Sources within Russia’s FSB allegedly tipped off Ukraine about the hit team because the sources didn’t support the war.

One might wonder, though, if there were other reasons behind the tip; were the Russian sources unhappy with the deployment of Chechens instead of Russian military?

~ ~ ~

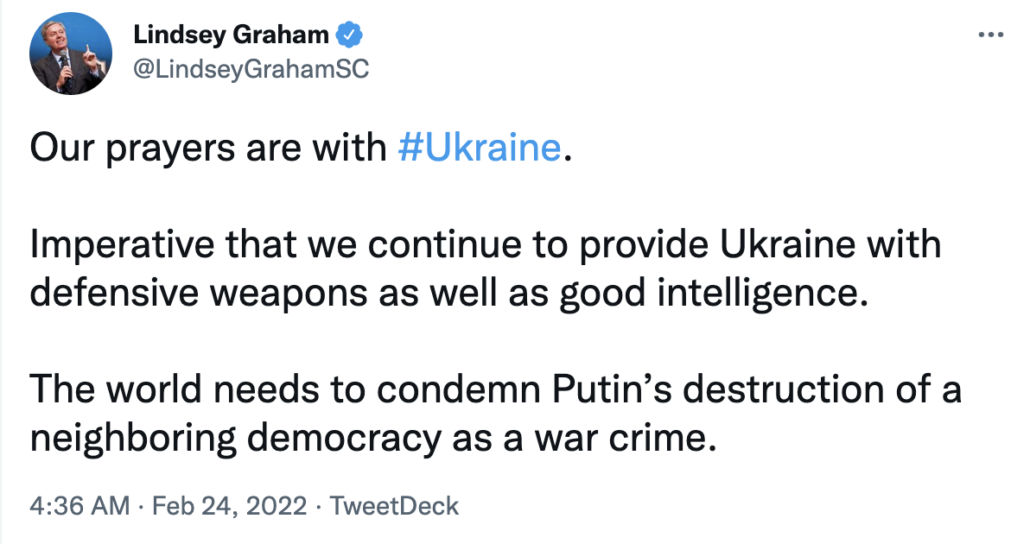

A few hours ago this tweet thread examined a issue affecting many of the Russian invasion vehicles.

The thread’s author believes it’s corruption in the Russian military system which has undermined essential maintenance rendering many vehicles unusable in the areas most affected by mud, while suggesting there aren’t enough tires in Russia’s military stores to replace those that fail in the field. It’s not just tire maintenance alone at issue, but inadequate tire care across the Russian vehicles deployed so far is daunting on its own.

All perfectly good points made in the thread, aligning with the corruption likely resulting from a military run under court politics and PR-maximization rather than effectiveness.

But there’s one more factor which hasn’t been raised across military analyses offered so far on Russia’s invasion.

Russia may have lost a substantial number of its military to COVID. The country’s all-cause death rate far exceeds that of the US, and we all know how badly the US has responded to the pandemic in no small part because of active measures by Russia encouraging anti-mask/anti-vax/anti-mandate/anti-lockdown/anti-science positions.

We can see anecdotally how many people are missing in our own workforce, in spite of the availability of highly-effective mRNA vaccines and one-shot adenovirus-vector vaccine and boosters.

Russia’s own vaccine, Sputnik V, has had difficulties beginning with acceptance from the vaccine research community, problems with manufacturing scale-up, and resistance within Russia itself. Assuming the numbers reported are accurate, less than 50% of Russians are vaccinated to date.

Is it possible what looks like poor maintenance isn’t merely the result of corruption, but the loss of personnel due to illness, hospitalization, deaths, and long COVID?

This challenge won’t be exclusive to Russia; Ukraine’s vaccination rate is bad or worse than Russia’s. But Ukraine isn’t having the same problems with equipment failures in the field, though Ukraine, too, has had its own problems with corruption.

Let’s hope we learn sooner rather than later just how much COVID affects a nation’s security.

~ ~ ~

And now for the two items pinned above:

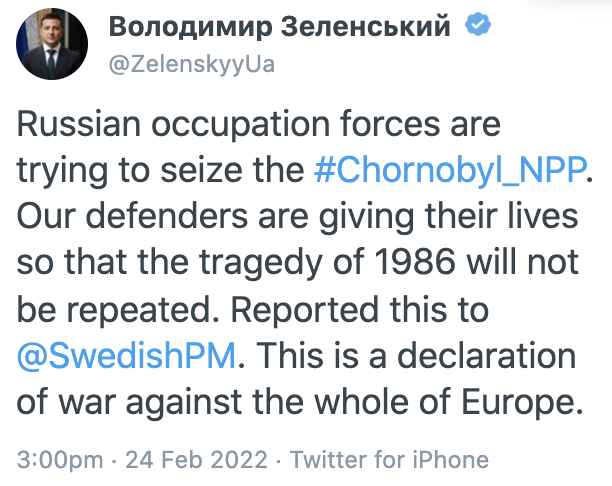

[1] Russia may have opted for naval maximization because it has a massive arctic coastline and the coast along Alaska it must patrol as well that near Japan. The arctic and Alaskan coasts are nearest to newer oil and gas development and pipelines like the Eastern Siberia Pacific Ocean I and II which serve Japan, China, and Korea. Much of Ukraine can be “reached” by missiles launched from vessels in the Black Sea, too.

But there may still be a problem if the video here is features a Russian naval vessel asking for fuel (it’s not clear what kind of Russian ship is involved here, it may be commercial).

If this is a Russian commercial vessel, how will the Russian navy handle these situations as access to supplies becomes more challenging?

[2] Doesn’t strike anyone as odd that Putin is relying on Muslim Chechen forces now when he’s launched so many attacks on Muslims through out his career? He’s been walking a fine line the relationship between what he perceives as the needs of Russia and biases which are barely restrained, like the support for Orthodox Serbs over Muslim Bosniaks, or the bombings of Syrians, or the blame placed on Muslim Chechens for the false flag Russian apartment bombings in 1999 which resulted in Putin’s election to the presidency.

~ ~ ~

UPDATE-1 — 11:30 PM ET —

Oh my. Somebody’s going to lose their job at a minimum.

Do look for more of Karl Muth’s replies after that tweet. We can’t tell if this is a budget problem, a corruption problem, or lax military standards, but whatever it is it’s not good for Russia.

Chinese-made radios, Chinese-made tires…what else is Chinese sourced in Russia’s invasion?