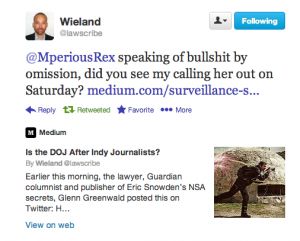

Apparently, Walter Katz — who tweets as “lawscribe / Wieland” — believes he succeeded in “calling me out” on “bullshit by omission” with this post on Saturday.

Apparently, Walter Katz — who tweets as “lawscribe / Wieland” — believes he succeeded in “calling me out” on “bullshit by omission” with this post on Saturday.

After he pointed me to it in apparent good faith on Saturday, I pointed out his own omissions, as well as two errors.

The errors were two-fold. First, he originally identified me as a lawyer, which I noted here I am not. He just updated his post to correct that and one other error (though seems not to have noted that I corrected him, as bmaz has in the past).

More problematic for his argument, he believes he caught me in an error in this passage:

But with its revised “News Media Policies,” DOJ gets us closer to having just that, an official press.

That’s because all the changes laid out in the new policy (some of which are good, some of which are obviously flawed) apply only to “members of the news media.” They repeat over and over and over and over, “news media.” I’m not sure they once utter the word “journalist” or “reporter.”

The “I’m not sure they once utter” comment clearly referred, in context, to DOJ in the News Media Policies. And, in point of fact, I’ve since done a search of the document, and DOJ does not once use the term “journalist” or “reporter” in it. It was a correct statement.

But Katz cites the FBI’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide — not the News Media Policies — and notes that it mentions “journalist.”

A freelance journalist may be considered to work for a news organization if the journalist has a contract with the news entity or has a history of publishing content.

Not only does the DOJ refer to “journalists” as Emptywheel said she was not “sure” if it ever did, it specifically provides for independent journalists who are either under contract with a publication or have published before.

Of course DOJ, in its history, has uttered the word “journalist” before, plenty of times. They have an entire department that deals with journalists! But I made no claim that DOJ, generally, had never used the word “journalist,” which would be an absurd claim. In spite of the fact that I noted this clear error in his piece, Katz did not correct his own piece when he took out his erroneous reference to me as a lawyer.

As to Katz’ omissions, he makes two, one substantive, and one of equal weight to one he complains I’ve made. First, he quotes my entire 2011 discussion on what the DIOG says about news media I included in my post except for this last bit:

The definition does warn that if there is any doubt, the person should be treated as media. Nevertheless, the definition seems to exclude a whole bunch of people (including, probably, me), who are engaged in journalism.

Now, it’s especially odd that he doesn’t quote that passage, because immediately after that blockquote, he paraphrases (arguably mis-paraphrases, since my argument is that I engage in journalism that should clearly be protected) the last part of the passage.

Emptywheel argues that she, as a blogger, is not included in the definition of “news media” even though she may be disseminating information to the public as defined in the Privacy Protection Act of 1980.

Not only would it have been useful for Katz to convey to his readers that I made that assertion in 2011 (when I had no regular affiliation with a news media organization and therefore it was a much clearer case). But by leaving out my note that “The definition does warn that if there is any doubt, the person should be treated as media,” he leaves out a key caveat I made. I noted that omission here.

Then he complains that I didn’t (in 2011, when I had no regular ties to news media) continue my citation from DIOG one sentence further. He introduced the “freelance journalist” passage, above, with this language:

Emptywheel neglected to include what it states in the DIOG definition of “news media” on page 157 directly after it notes that a national reporter with a personal blog is covered by the guidelines:

But curiously, Katz chose to stop his own citation there, leaving out the sentence that immediately followed:

Publishing a newsletter or operating a website does not by itself qualify an individual as a member of the news media.

The passage certainly reinforces my point (as do a few other lines in the definition), and was part of what might have disqualified me — in 2011, when I made the statement about not qualifying — as a member of the news media. I noted that Katz omission here.

Of course, these mutual “gotchas” would be mooted had Katz simply not clipped my own quote and instead (mis)paraphrased my 2011 comment so as to skip my caveat. Nevertheless it is that omission — the sentence that my caveat would have incorporated — that he thinks demonstrates my “bullshit by omission.”

Incidentally, Katz also chose to clip my sentence that said some of these changes were good. I guess that would have harmed his claim that I “do[] not see the new guidelines as much progress.”

Finally, Katz fails, according to his own terms, in one other way. He embraces the term “news media” because it allows DOJ to be consistent across its document.

Emptywheel continutes:

They repeat over and over and over and over, “news media.” I’m not sure they once utter the word “journalist” or “reporter.” And according to DOJ’s Domestic Investigation and Operations Guide, a whole slew of journalists are not included in their definition of “news media.”

Since I consult with law enforcement agencies on writing policy, the fact the DOJ generally uses one term, “news media,” is of no moment and, in fact, is desirable for clarity purposes.

But, of course, a key part of these policies (indeed, the one Katz focuses on in his post) is in addressing the Privacy Protection Act. And as I noted in my post, the PPA uses an entirely different standard than “news media” — it applies to “individuals who have a purpose to disseminate information to the public.”

The Privacy Protection Act of 1980 (PPA), 42 U.S.C. § 2000aa, generally prohibits the search or seizure of work product and documentary materials held by individuals who have a purpose to disseminate information to the public. The PPA, however, contains a number of exceptions to its general prohibition, including the “suspect exception” which applies when there is “probable cause to believe that the person possessing such materials has committed or is committing a criminal offense to which the materials relate,” including the “receipt, possession, or communication of information relating to the national defense, classified information, or restricted data “under enumerated provisions. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000aa(a)(1) and (b)(1). Under current Department policy, a Deputy Assistant Attorney General may authorize an application for a search warrant that is covered by the PPA, and no higher level reviews or approvals are required.

First, the Department will modify its policy concerning search warrants covered by the PPA involving members of the news media to provide that work product materials and other documents may be sought under the “suspect exception” of the PPA only when the member of the news media is the focus of a criminal investigation for conduct not connected to ordinary newsgathering activities. Under the reviews policy, the Department would not seek search warrants under the PPA’s suspect exception if the sole purpose is the investigation of a person other than the member of the news media. [my emphasis]

So by using “news media,” DOJ has actually shifted from one definition to another in the course of two paragraphs in discussing the topic that Katz focuses on as the reason for the new guidelines. I noted that here.

Now, to be fair to Katz, when I linked to my 2011 analysis of DIOG, I didn’t obviously identify it (beyond the link) as 18 month old analysis, so he may have been confused about that (though he appears to have clicked through, at least using my link to DIOG). So perhaps when he was bragging about having called out my “bullshit by omission” he may not have understood the errors such claims introduced in his own writing. My apologies if that’s the case.

But none of that explains why Katz went into his post and made corrections, yet didn’t correct the clear error about my reference to “journalist.”