In December, I wrote a post noting that NSA personnel performing analysis on PATRIOT-authorized metadata (both phone or Internet) can choose to contact chain on just that US-collected data, or — in what’s call a “federated query” — on foreign collected data, collected under Executive Order 12333, as well. It also appears (though I’m less certain of this) that analysts can do contact chains that mix phone and Internet data, which presumably is made easier by the rise of smart phones.

In December, I wrote a post noting that NSA personnel performing analysis on PATRIOT-authorized metadata (both phone or Internet) can choose to contact chain on just that US-collected data, or — in what’s call a “federated query” — on foreign collected data, collected under Executive Order 12333, as well. It also appears (though I’m less certain of this) that analysts can do contact chains that mix phone and Internet data, which presumably is made easier by the rise of smart phones.

Section 215 is just a small part of the dragnet

This is one reason I keep complaining that journalists reporting the claim that NSA only collects 20-30% of US phone data need to specify they’re talking about just Section 215 collection. Because we know, in part because Richard Clarke said this explicitly at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing last month, that Section “215 produces a small percentage of the overall data that’s collected.” At the very least, the EO 12333 data will include the domestic end of any foreign-to-domestic calls it collects, whether made via land line or cell. And that doesn’t account for any metadata acquired from GCHQ, which might include far more US person data.

The Section 215 phone dragnet is just a small part of a larger largely-integrated global dragnet, and even the records of US person calls and emails in that dragnet may derive from multiple different authorities, in addition to the PATRIOT Act ones.

SPCMA provided NSA a second way to contact chain on US person identifiers

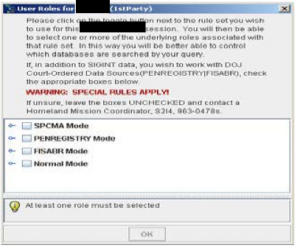

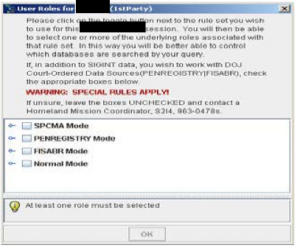

With that background, I want to look at one part of that dragnet: “SPCMA,” which stands for “Special Procedures Governing Communications Metadata Analysis,” and which (the screen capture above shows) is one way to access the dragnet of US-collected (“1st person”) data. SPCMA provides a way for NSA to include US person data in its analysis of foreign-collected intelligence.

According to what is currently in the public record, SPCMA dates to Ken Wainstein and Steven Bradbury’s efforts in 2007 to end some limits on NSA’s non-PATRIOT authority metadata analysis involving US persons. (They don’t call it SPCMA, but the name of their special procedures match the name used in later years; the word, “governing,” is for some reason not included in the acronym)

Wainstein and Bradbury were effectively adding a second way to contact chain on US person data.

They were proposing this change 3 years after Collen Kollar-Kotelly permitted the collection and analysis of domestic Internet metadata and 1 year after Malcolm Howard permitted the collection and analysis of domestic phone metadata under PATRIOT authorities, both with some restrictions, By that point, the NSA’s FISC-authorized Internet metadata program had already violated — indeed, was still in violation — of Kollar-Kotelly’s category restrictions on Internet metadata collection; in fact, the program never came into compliance until it was restarted in 2010.

By treating data as already-collected, SPCMA got around legal problems with Internet metadata

Against that background, Wainstein and Bradbury requested newly confirmed Attorney General Michael Mukasey to approve a change in how NSA treated metadata collected under a range of other authorities (Defense Secretary Bob Gates had already approved the change). They argued the change would serve to make available foreign intelligence information that had been unavailable because of what they described as an “over-identification” of US persons in the data set.

NSA’s present practice is to “stop” when a chain hits a telephone number or address believed to be used by a United States person. NSA believes that it is over-identifying numbers and addresses that belong to United States persons and that modifying its practice to chain through all telephone numbers and addresses, including those reasonably believed to be used by a United States person, will yield valuable foreign intelligence information primarily concerning non-United States persons outside the United States. It is not clear, however, whether NSA’s current procedures permit chaining through a United States telephone number, IP address or e-mail address.

They also argued making the change would pave the way for sharing more metadata analysis with CIA and other parts of DOD.

The proposal appears to have aimed to do two things. First, to permit the same kind of contact chaining — including US person data — authorized under the phone and Internet dragnets, but using data collected under other authorities (in 2007, Wainstein and Bradbury said some of the data would be collected under traditional FISA). But also to do so without the dissemination restrictions imposed by FISC on those PATRIOT-authorized dragnets.

In addition (whether this was one of the goals or not), SPCMA defined metadata in a way that almost certainly permitted contact chaining on metadata not permitted under Kollar-Kotelly’s order.

“Metadata” also means (1) information about the Internet-protocol (IP) address of the computer from which an e-mail or other electronic communication was sent and, depending on the circumstances, the IP address of routers and servers on the Internet that have handled the communication during transmission; (2) the exchange of an IP address and e-mail address that occurs when a user logs into a web-based e-mail service; and (3) for certain logins to web-based e-mail accounts, inbox metadata that is transmitted to the user upon accessing the account.

Some of this information — such as the web-based email exchange — almost certainly would have been excluded from Kollar-Kotelly’s permitted categories because it would constitute content, not metadata, to the telecoms collecting it under PATRIOT Authorities.

Wainstein and Bradbury appear to have gotten around that legal problem — which was almost certainly the legal problem behind the 2004 hospital confrontation — by just assuming the data was already collected, giving it a sort of legal virgin birth.

Doing so allowed them to distinguish this data from Pen Register data (ironically, precisely the authority Kollar-Kotelly relied on to authorize PATRIOT-authorized Internet metadata collection) because it was no longer in motion.

First, for the purpose of these provisions, “pen register” is defined as “a device or process which records or decodes dialing, routing, addressing or signaling information.” 18 U.S.C. § 3127(3); 50 U.S.C. § 1841 (2). When NSA will conduct the analysis it proposes, however, the dialing and other information will have been already recorded and decoded. Second, a “trap and trace device” is defined as “a device or process which captures the incoming electronic or other impulses which identify the originating number or other dialing, routing, addressing and signaling information.” 18 U.S.C. § 3127(4); 50 U.S.C. § 1841(2). Again, those impulses will already have been captured at the point that NSA conducts chaining. Thus, NSA’s communications metadata analysis falls outside the coverage of these provisions.

And it allowed them to distinguish it from “electronic surveillance.”

The fourth definition of electronic surveillance involves “the acquisition by an electronic, mechanical, or other surveillance device of the contents of any wire communication …. ” 50 U.S.C. § 1802(f)(2). “Wire communication” is, in turn, defined as “any communication while it is being carried by a wire, cable, or other like com1ection furnished or operated by any person engaged as a common carrier …. ” !d. § 1801 (1). The data that the NSA wishes to analyze already resides in its databases. The proposed analysis thus does not involve the acquisition of a communication “while it is being carried” by a connection furnished or operated by a common carrier.

This legal argument, it seems, provided them a way to carve out metadata analysis under DOD’s secret rules on electronic surveillance, distinguishing the treatment of this data from “interception” and “selection.”

For purposes of Procedure 5 of DoD Regulation 5240.1-R and the Classified Annex thereto, contact chaining and other metadata analysis don’t qualify as the “interception” or “selection” of communications, nor do they qualify as “us[ing] a selection term,” including using a selection term “intended to intercept a communication on the basis of … [some] aspect of the content of the communication.”

This approach reversed an earlier interpretation made by then Counsel of DOJ’s Office of Intelligence and Policy Review James A Baker.

Baker may play an interesting role in the timing of SPCMA. He had just left in 2007 when Bradbury and Wainstein proposed the change. After a stint in academics, Baker served as Verizon’s Assistant General Counsel for National Security (!) until 2009, when he returned to DOJ as an Associate Deputy Attorney General. Baker, incidentally, got named FBI General Counsel last month.

NSA implemented SPCMA as a pilot in 2009 and more broadly in 2011

It wasn’t until 2009, amid NSA’s long investigation into NSA’s phone and Internet dragnet violations that NSA first started rolling out this new contact chaining approach. I’ve noted that the rollout of this new contact-chaining approach occurred in that time frame.

Comparing the name …

SIGINT Management Directive 424 (“SIGINT Development-Communications Metadata Analysis”) provides guidance on the NSA/ CSS implementation of the “Department of Defense Supplemental Procedures Governing Communications Metadata Analysis” (SPCMA), as approved by the U.S. Attorney General and the Secretary of Defense. [my emphasis]

And the description of the change …

Specifically, these new procedures permit contact chaining, and other analysis, from and through any selector, irrespective of nationality or location, in order to follow or discover valid foreign intelligence targets. (Formerly analysts were required to determine whether or not selectors were associated with US communicants.) [emphasis origina]

,,, Make it clear it is the same program.

NSA appears to have made a few changes in the interim. Read more →