Working Thread: NSL IG Report

I give up. I’m going to have to do a working thread on the IG Report on FBI’s use of NSLs. Here goes. References are to page numbers, not PDF numbers (PDF numbers are page+15).

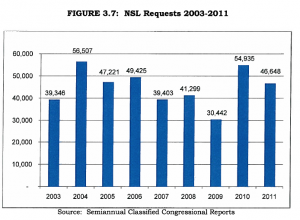

ix: The report noted that NSL numbers dropped off what they had been 2007 to 2009. It speculates that may have been because of heightened scrutiny. I wonder it wasn’t because they were misusing the phone and Internet dragnet programs and getting the information that way. In 2009, after which the NSL numbers grew again, Reggie Walton shut that option down.

x: About half of NSLs during this period were used to investigate USPs.

x: “certain Internet providers refused to provide electronic communication transactional records in response to ECPA NSLs.”

xii: They’re hiding the current status of permitting the use of NSLs to get journo contacts. Which would seem to confirm they are doing so.

xiii: They’re also hiding the status of the OLC memo they used to say they could get phone records voluntarily (see this post for why). They don’t hide things very well.

2: It just makes me nuts we’re only now reviewing NSL use from 2009. Know what has happened in the interim, for example? A key player in this stuff, Valerie Caproni, has become a lifetime appointed judge.

11: Report notes that FBI tends to always use “overproduction” whether or not it was unauthorized or simply too broad.

17: Footnote 35 seems to suggest they have exceptions to the mandatory reporting requirements. What could go wrong?

39: So as recently as 2009, the tracking system did not alert OGC of manual NSLs in some percentage of the cases.

57 The numbers reported to Congress are off from the numbers shown to IG by as much as 2,800.

58: Love footnote 73, which aims to explain why the NSL numbers reported to Congress are significantly lower than those reported to OIG.

After reviewing the draft of this report, the FBI told the OIG for the first time that the NSL data provided to Congress would almost never match the NSL data provided to the OIG because the NSL data provided to Congress includes NSLs issued from case files marked “sensitive,” whereas the NSL data provided to the OIG does not. According to the FBI, the unit that provided NSL data to the OIG does not have access to the case files marked “sensitive” and was therefore unable to provide complete NSL data to the OIG. The assertion that the FBI provided more NSL data to Congress than to the OIG does not explain the disparities we found in this review, however, because the disparities we found reflected that the FBI reported fewer NSL requests to Congress than the aggregate totals.

The FBI just gives up on 100% accuracy in its NSL numbers.

After reviewing the draft of this report, the FBI told the OIG that while 100 percent accuracy can be a helpful goal, attempting to obtain 100 percent accuracy in the NSL subsystem would create an undue burden without providing corresponding benefits. The FBI also stated that it has taken steps to minimize error to the greatest extent possible.

59: On the discrepancies, OIG points out the obvious:

[T]he total number of manually generated NSLs that the FBI inspectors identified is relatively small compared to the total number of 30,442 NSL requests issued by the FBI that year. What remains unknown, however is, whether the FBI inspectors identified all the manually identified generally NSLs issued by the FBI or whether a significant number remains unaccounted for and unreported.

61: The database tracking 2007 requests — a year where there were discrepancies for 215 orders too — “is retired and unavailable.”

62: The report doesn’t have subscriber only data, which I suspect is obtained in bulk.

63: There is a significant change in the make-up of what FBI is getting in 2009, from subscriber records and toll and financial records in 2008 to toll records, then subscriber and electronic communication records in 2009. I strongly suspect that says some of the 214 and 215 collection moved to NSLs.

71: Apparently it was the release of an earlier OLC memo that led at least 2 Internet companies to refuse NSLs.

The decision of these [redacted] Internet companies to discontinue producing electronic communication transactional records in response to NSLs followed public release of a legal opinion issued by the Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) regarding the application of ECPA Section 2709 to various types of information. The FBI General Counsel sought guidance from the OLC on, among other things, whether the four types of information listed in subsection (b) of Section 2709 — the subscriber’s name, address, length of service, and local and long distance toll billing records — are exhaustive or merely illustrative of the information that the FBI may request in an NSL. In a November 2008 opinion, the OLC concluded that the records identified in Section 2709(b) constitute the exclusive list of records that may be obtained through an ECPA NSL.

Although the OLC opinion did not focus on electronic communication transaction records specifically, according to the FBI, [redacted] took a legal position based on the opinion that if the records identified in Section 2709(b) constitute the exclusive list of records that may be obtained through an ECPA NSL, then the FBI does not have the authority to compel the production of electornic communication transactional records because that term does not appear in subsection (b).