On Same Day Alexander Tells BlackHat, “Their Intent Is to Find the Terrorist That Walks Among Us,” We See NSA Considers Encryption Evidence of Terrorism

Thirty minutes into his speech at BlackHat yesterday, Keith Alexander said,

Remember: their intent is not to go after our communications. Their intent is to find the terrorist walks among us.

He said that to a room full of computer security experts, the group of Americans probably most likely to encrypt their communications, even hiding their location data.

At about the same time Alexander made that claim, the Guardian posted the full slide deck from the XKeyscore program it reported yesterday.

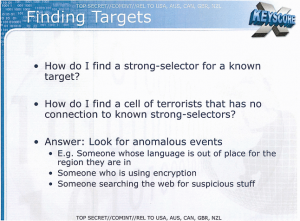

How do I find a cell of terrorists that has no connection to known strong-selectors?

Answer: Look for anomalous events

Among other things, the slide considers this an anomalous event indicating a potential cell of terrorists:

- Someone who is using encryption

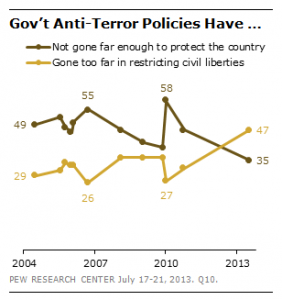

Meanwhile, note something else about Alexander’s speech.

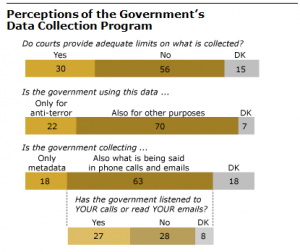

13:42 into his speech, Alexander admits the Section 702 collection (this is true of XKeyscore too — but not the Section 215 dragnet, except in its use on Iran) also supports counter-proliferation and cybersecurity.

That is the sole mention in the entire speech of anything besides terrorism. The rest of it focused exclusively on terror terror terror.

Except, of course, yesterday it became clear that the NSA considers encryption evidence of terrorism.

Increasingly, this infrastructure is focused intensively on cybersecurity, not terrorism. That’s logical; after all, that’s where the US is under increasing attack (in part in retaliation for attacks we’ve launched on others). But it’s high time the government stopped screaming terrorism to justify programs that increasing serve a cybersecurity purpose. Especially when addressing a convention full of computer security experts.

But maybe Alexander implicitly admits that. At 47:12, Alexander explains that the government needs to keep all this classified because (as he points into his audience),

Sitting among you are people who mean us harm.

(Note after 52:00 a heckler notes the government might consider BlackHat organizer Trey Ford a terrorist, which Alexander brushes off with a joke.)

It’s at that level, where the government considers legal hacker behavior evidence of terrorism, that all reassurances start to break down.

Update: fixed XKeystroke for XKeyscore–thanks to Myndrage. Also, Marc Ambinder reported on it in his book.

Update: NSA has now posted its transcript of Alexander’s speech. It is 12 pages long; in that he mentioned “terror” 27 times. He mentions “cyber” just once.