DOJ Did Not Fulfill Legally Required Disclosure on Section 215 to Congress Until After PATRIOT Reauthorization

In the Guardian’s superb summary of the importance of the NSA leaks, Zoe Lofgren challenges the claims that Congress has received all the documents NSA claims it has gotten.

I do serve on the Judiciary Committee and various statements have been made that the Judiciary Committee members were told about all of this and those statements are untrue, not the facts, we have not been provided the documents that the Agency said that we were.

In a Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board today, NSA General Counsel Raj De and ODNI General Counsel Robert Litt both repeated such claims (these are from my notes on twitter; I’ll check my transcription later). De said that Section 215 “had all indicia of official legitimacy” which in part came because it was “twice reauthorized by Congress with full information from exec.” And Litt said they are “by statute required to provide copies [of FISC documents] to both houses. They got materials relating to this [Section 215] program.”

Obviously, we know De is wrong, and he must know it, because a sufficiently large block of Congressmen never had the opportunity to read the Executive’s official notice to make the difference in the 2011 reauthorization. His statement is a clear lie.

But I’m just as interested in Litt’s claim (which would rely on notice to the Judiciary and Intelligence Committees).

This most recent I Con dump provides some evidence that illuminates Lofgen’s implicit dispute of Litt’s claims. Remember this paragraph, which is one of the most specific claims about what notice the Administration gave to Congress about using Section 215 to authorize the phone dragnet.

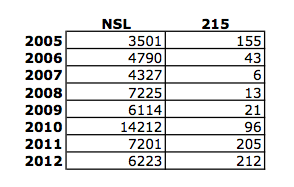

Moreover, in early 2007, the Department of Justice began providing all significant FISC pleadings and orders related to this [Section 215] program to the Senate and House Intelligence and Judiciary committees. By December 2008, all four committees had received the initial application and primary order authorizing the telephony metadata collection. Thereafter, all pleadings and orders reflecting significant legal developments regarding the program were produced to all four committees.

As I noted in this post, the specific language (in bold) regarding the first, May 2006, authorization of the phone dragnet at least suggested, in this context, there wasn’t an opinion at all, as did a lot more evidence. But recent reporting strongly suggests there was (see this post where I argue this is likely the phone dragnet opinion).

Government lawyers have told the ACLU that they are withholding at least two significant FISC opinions — one from 2008 and one from 2010 — relating to the Patriot Act’s Section 215, or “business records” provision.

This would seem to indicate that Congress was not provided the original 2006 opinion (as distinct from the application and primary order) “by December 2008.”

With that mind, consider this document released by the I Con, an August 16, 2010 memo from Office of Legislative Affairs Assistant Attorney General Ronald Weich to the Chairs of the Judiciary and Intelligence Committees.

Pursuant to section 1871 of United States Code Title 50, we are providing the Committees with copies of the remaining decisions, orders, or opinions issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, and pleadings, applications, or memoranda of law associated therewith, that contain significant constructions or interpretations of any provision of FISA during the five-year period ending July 10, 2008. See 50 U.S.C. § 1871(c)(2). We have provided similar materials for the same time period.

Now remember, while ODNI made a big show of releasing these documents, they released them as part of the ACLU’s FOIA for documents on Section 215 and all the documents released pertain to Section 215. I Con describes the memo as referring to “several documents to the Congressional Intelligence and Judiciary Committees relating to NSA collection of bulk telephony metadata under Section 501 of the FISA, as amended by Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act,” confirming they pertain to Section 215.

The Patriot Act was reauthorized in February 2010.

At a minimum, this suggests the White Paper provided in August may have been highly misleading. When it said “Thereafter, all pleadings and orders reflecting significant legal developments regarding the program were produced to all four committees,” it did not mean that by December 2008, the four oversight committees had all the significant opinions in hand. Even assuming the Weich brief was correct, which Lofgren’s comment suggests it might not be, they didn’t get around to handing over opinions pertaining to Section 215 going back to July 10, 2003 until August 2010. That period — July 10, 2003 to July 10, 2008 — would cover both the July 2004 Colleen Kollar-Kotelly opinion authorizing using the Pen Register/Trap and Trace to collect Internet metadata, and the May 2006 opinion authorizing the phone dragnet. While we don’t know that the Kollar-Kotelly opinion was withheld until 2010, the language of the White Paper (which suggests the opinion itself was not provided) strongly suggests the May 2006 one was.

The law requiring such disclosure, 50 U.S.C. § 1871(c)(2), was part of the FISA Amendments Act, so had been in place for a full year by the time the PATRIOT Act reauthorization got started, yet DOJ didn’t get around to complying with it until 2 years after the law passed. And the law specifically requires disclosure of both the PR/T&T and the Section 215 authorities.

The possibility that DOJ did not turn over the original phone dragnet opinion is utterly damning given David Kris’ suggestion that the initial approval of the phone dragnet — the 2006 opinion — may have been erroneous.

More broadly, it is important to consider the context in which the FISA Court initially approved the bulk collection. Unverified media reports (discussed above) state that bulk telephony metadata collection was occurring before May 2006; even if that is not the case, perhaps such collection could have occurred at that time based on voluntary cooperation from the telecommunications providers. If so, the practical question before the FISC in 2006 was not whether the collection should occur, but whether it should occur under judicial standards and supervision, or unilaterally under the authority of the Executive Branch.

[snip]

The briefings and other historical evidence raise the question whether Congress’s repeated reauthorization of the tangible things provision effectively incorporates the FISC’s interpretation of the law, at least as to the authorized scope of collection, such that even if it had been erroneous when first issued, it is now—by definition—correct.

David Kris at least entertains the possibility that the original May 2006 opinion was “erroneous,” but points to Congress’ reauthorization of the PATRIOT Act to claim it had incorporated FISC’s interpretation of the law.

But now we know that DOJ did not provide all of FISC’s significant opinions pertaining to Section 215 to the key oversight committees until August 16, 2010, over two years after they were obligated to do so — and the plain language of the White Paper strongly suggests that DOJ did not provide the key May 2006 opinion to the oversight committees.

This doesn’t yet prove that DOJ withheld the May 2006 opinion that Kris suggests might be “erroneous” until after Congress reauthorized the PATRIOT Act. But it strongly suggests that is the case.

Update: PATRIOT Act Reauthorization line moved per Anonster’s suggestion.

Update: Added the language I Con used to describe the documents handed over in August 2010.