How FISA Dockets (Appear To) Work and Why Snowden Likely Got Few or No PayPal Documents

Because Bill Binney made an observation about the high docket number of the phone dragnet order released this year, Sibel Edmonds has decided that Glenn Greenwald is hiding a bunch of Edward Snowden documents to protect Pierre Omidyar showing PayPal cooperated with NSA.

Here’s what Binney said, according to him.

Unfortunately, Sibel attributes some of her words to me. I do not know that PAYPAL is involved – only that financial data is being used by NSA. And, based on the “BR” number 13/80 on the Verizon court order to give records to NSA, I estimated that this program involved 78 companies. These would include: telecom’s, internet service providers, banks/finance/credit cards, travel, plus others. So, there’s a lot of business data being collected by NSA and the FBI. In the future, if I am to be quoted, I will have to I will have to insist on a pre-publication review. [my emphasis]

Now, like Peter Kofod, I don’t doubt that PayPal gives a ton of data to the national security state (more on what probably happens below).

But Binney’s comment appears to be based on a misunderstanding of how the FISA docket numbering works (though not one that changes his observation that “there’s a lot of business data being collected by NSA and the FBI”): that each docket pertains to a different company.

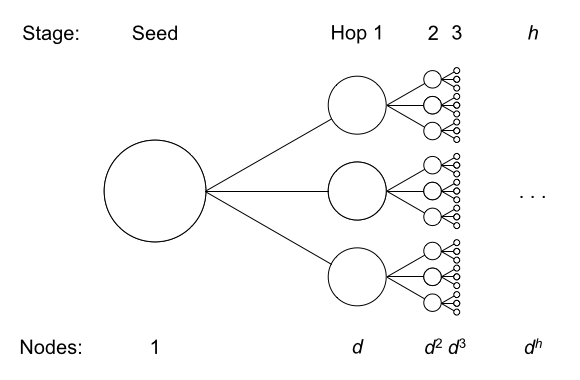

Given the filings we’ve seen from voluminous years — particularly 2009 — it is clear that DOJ uses one docket for all providers on a particular order. For example, 3 of the 4 docket numbers used for the phone dragnet in 2009 were 08-13, 09-06, and 09-13. For the entire 3 month period the primary order covers, all the orders and correspondence related to that primary order bears the original docket number. Even in the case where Judge Walton cut off and then resumed production (see 09-13 above) from just one provider got handled in that docketing system. The now public FISC docket appears to continue this practice, with BR 13-109 and BR 13-158 including all the correspondence on a particular order (in addition, there are the Misc dockets for lawsuits, and the 2007 docket tied to Protect America Act for the Yahoo challenge).

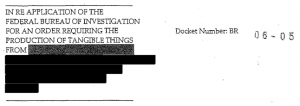

And over the years, the list of providers included on the dockets appears to have gotten much longer. Here’s the redacted list of providers from the original 2006 order:

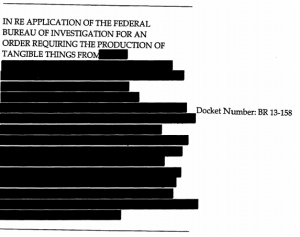

Here’s the redacted list of providers from the most recent order:

The additional providers are probably smaller providers, as well as VOIP providers.

So just 4 and on rare occasions 5 of the Section 215 (“BR”) docket numbers in any given year (and, for the life of the program, just 4 of the PR/TT docket numbers) covered all the providers.

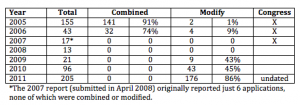

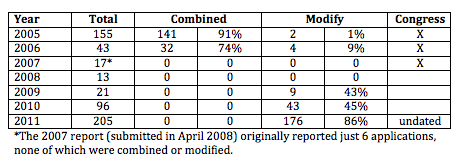

But that may, in fact, mean far more companies are getting Section 215 orders, even bulk orders. As I laid out in this post, the numbers of Section 215 orders have gone up in the last several years (Julian Sanchez has speculated that previously some of this collection was done via National Security Letter, which is a pretty good bet).

And as they’ve gone up, the FISA Court has been modifying far more orders — it modified 86% of the orders in 2011. It has been modifying orders to add minimization procedures (it modified 176 orders in 2011 to add minimization requirements). Given that you only need to have significant minimization procedures if you’re getting a lot of innocent people’s data, and given that these orders would also be on a 90-day cycle, that may mean there were 44 bulk collection programs in 2011.

But, as Binney said, that’s going to include a lot of different kinds of companies. We know they’ve used Section 215 to collect precursor chemical purchase records. They likely cover credit cards records, other financial records, gun purchases, health and medical records, and other computer records. There have even been questions about using Section 215 to collect URL search terms.

PayPal is one possible or even likely recipient of these, but only one out of a bunch. Read more →