Pete Hegseth and the Radical Queer Wing of Al-Qaeda

Where Murder Dances With Law

A while back, maybe a decade and change ago during the Obama administration, I was drinking with some nerdy friends in a San Francisco hackerspace. We got to talking about National Security law, hacktivism, and terrorism. I had been Wired’s correspondent on Anonymous, and probably understood The hacktivist collective better than anyone. They had recently tore through the net, hacking companies and governments like they were wet paper towels. I was explaining to my fellow nerds that Anonymous was very similar to Al-Qaeda. Though in form only, not in content.

There was no crossover between the shit-talking data “liberators” I had embedded with in 2011/12 and the religious extremist terrorist group founded by Osama bin Laden. They had no members in common, (that I ever knew of) and the ethos of the two groups were so far apart as to not just be in opposition, but to be mutually unintelligible.

A lawyer friend also drinking with us explained that US law struggled to categorize these kinds of leaderless collectives. Al-Qaeda has leaders, but they’re more the winners of a local popularity contest than they are formally appointed, ordained, coronated, or what not.

The answer legislators came up to deal with these groups with was a bit of legalistic nailing jello to a wall. Much like Anonymous, if you wanted to go start your own Al-Qaeda cell, you just did it. It was entirely possible that as an Al-Qaeda terrorist, you would talk your friends into doing some terrorism with you. Then presumably go and blow something up, possibly yourself, possibly random innocent victims, or both.

Anons also would pick a target, usually a perceived terrible company or government, and try to hack the hell out of it. They’d bring down servers, steal secret data and dump it on the net for anyone to see, jam the websites of badly behaved companies, and so forth.

By being essentially more internet/media brand than traditional organization, both Al-Qaeda and Anonymous were particularly hard to prosecute as a group, or even legislate against. They were collectives architected by speech acts, mostly on the internet. Law enforcement could and did go after both groups, but to do so they had to find someone breaking a law and pursue them for that one single act of law breaking.

Unlike the Mob or a criminal gang, there was no illicit organization to target, there was just “the memes.” When you caught one Anon, you caught exactly one Anon. Even in the case of the notorious Anonymous operation run by the FBI, they only managed to arrest one person. (That was a shit show, mainly put together to make Shawn Henry’s exit from the FBI and move over to Crowdstrike as lucrative as possible, as far as I could tell.)

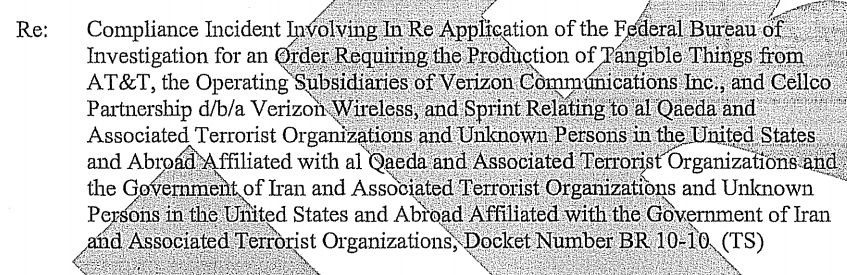

Lawmakers eventually found a way around the strange status of groups like Al-Qaeda, but it was pretty terrible lawmaking. To make a very long set of laws and recent history very short, the provision basically amounted to this: if you called yourself Al-Qaeda, you were Al-Qaeda. That meant you could be killed, on sight, without due process, because you were Al-Qaeda. That name meant that you were an enemy of the state.

I found this situation so absurd that I started the Radical Queer Wing of Al-Qaeda. I was curious how I could be (theoretically) the most murderable non-combatant possible, both by my own government and a terrorist organization. We (mostly me) were a pretty tame branch of Al-Qaeda. All our bombs were glitter bombs, and we touted ourselves as the most fabulous of the Al-Qaedas. Straight people were not allowed to join our Al-Qaeda, but they could hang, if they were cool.

The lawyer friend (who declined our offer to join the Radical Queer Wing of Al-Qaeda, as he was straight and also definitely not going to do that) confirmed that, yes, maybe, even probably, I could be killed on sight, without due process, under the existing law. He pressed me to make sure I understood that no one was going to do that, it would simply never happen or even come up. This was all a hypothetical. “But they could,” I replied, “And that’s the important part!” The weirdly violent ridiculousness of the situation was the point.

We all continued drinking. Later, I had a few Radical Queer Wing of Al-Qaeda brunches at my co-living space in San Francisco, before getting bored and running off to find new ways to get in fights with, and make fun of, my government.

A 21st Century of Rot

George Bush’s 2001 PATRIOT act had so many horrific provisions to fight and make fun of, and even as some parts were repealed, others persisted into future administrations, and still others became not just part of law, but also part of culture. The War on Terror normalized killing the bad guys, because they were bad. Because we were told they were bad. Americans mostly learned not to question their badness, or the slow and sneaky erosion of our rights to the presumption of innocence.

Obama not only kept the PATRIOT Act provisions in place, he expanded them, including the open killing of children. Obama loved murder by drone. Famously, he killed a 16-year-old American citizen, Abdulrahman Anwar al-Awlaki, a few days after he’d already killed the kid’s father. Killing people with drones in the Obama era became common enough that it didn’t really make the news after a while. Obama seemed to have loved a good techno-assassination.

He held “Terror Tuesdays” every week where he’d work with staff to pick a new person to kill. Presumably, what Trump calls “bad hombres,” but are, one way or another, still people. They were people we were once required to provide with due process, to be presumed innocent if arrested, be they citizens of the United States or not, because that’s who we were supposed to be. But now we call it war, and then murder some guys because they’re in boats off the coast of Venezuela.

Well before Trump, we had left the principles of the Fifth Amendment (due process) dying in a ditch. He’s gone on to attack free speech. Trump shat on the right to assemble (using AI), denied literally thousands the right to trial before forced deportation. He even tried to strike out birthright citizenship with a stroke of his sharpie. His government has engaged in unreasonable searches and seizures. Trump has tried to confiscate the rights of both the people and the States. Trump did not merely come to weaken Bill of Rights, he came to destroy it altogether. In this task, he has faced barely any resistance, in part because the last few presidents loosened the bolts on the system for him.

No one should be surprised at this point that Whiskey Pete Hegseth kills people with impunity. He’s tacked on “terrorist” to a narco- prefix to make the whole thing look vaguely legal, as if that one magical word abrogates all human rights. But “Narco-terrorist” is just a term he made up to justify what remains murder. That is what is going on in the Caribbean. It’s the logical conclusion of what I was trying to parody all those years ago with my Al-Qaeda glitter bombs — laws that allow for extrajudicial killing, based on the slippery idea that anything we don’t like is terrorism, can only arrive at the place we are now. It’s not quite within legal regimes, but colored by laws that seem to contradict the Constitution in both meaning and plain language.

But here we are, and here is where we have to come back from.

Pete Hegseth’s campaign of terror against poor fishermen in the Caribbean may have taken us out of the rule of law more than any other single act, but Bush and Obama prepared the ground for Trump. This situation would be recognizable to the Founding Fathers as the kind of thing that we rebelled against those centuries ago.

Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda never really had the power to destroy America, anymore than gays or communists did. But he invited us to destroy ourselves. Standing on the shoulders of the last few administrations, Trump has taken up bin Laden’s dream of making America into a pseudo-religious hellscape of gerontocratic corruption and vice, just with more fake Jesus and less fake Muhammad.

It’s Not Too Late for US

We don’t have to settle for this. We can save America. Somewhere beneath the layers of corporate corruption, bigotry, and jingoism, we still have values. We are often good neighbors. Americans have some of the highest rates of volunteerism in the world — we don’t just sit at home, we work the problems around us, and we go work abroad. We donate, but we also get off our butts and help people. To defeat that, the ghouls running our government have tried to convince us that no one else matters. Right now, we have to remember who we are and take care of each other. We have to protect ourselves and our communities against the avaricious.

This administration tried to make us selfish. But they are failing. According to polling by YouGov and the Economist, Trump has 38% approval, and falling. The message that we should work together to make our world a better place was key to Zohran Mamdani’s recent win in New York, and it’s key to how we rally Americans against this venal administration. But it does mean we have to look past our own troubles and begin to engage in community together.

Trump voters voted on prices more than anything else. They didn’t see the larger picture, but it’s coming into focus now.

Donald Trump’s grand bet is that our selfishness will keep us weak and atomized, but we can prove him wrong. When we reach out and take care of each other, when we organize, rally, and commit, we build the community we need to defeat this rising darkness.

A previous version of this piece described Obama as targeting Abdulrahman Anwar al-Awlaki, which was incorrect He was killed in a targeted attack, but he was not the target himself. I regret the error.