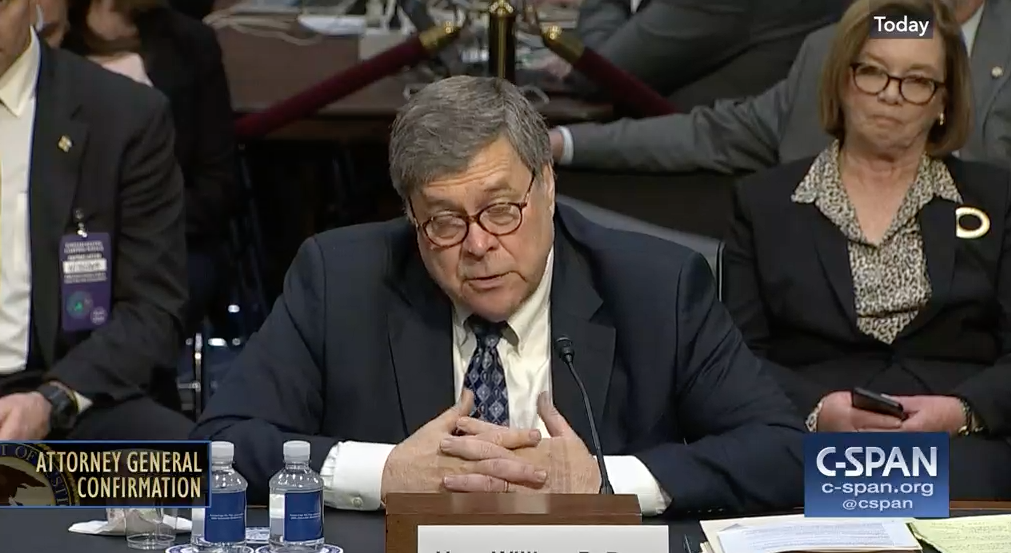

Sidney Powell Complains That Peter Strzok Is Too OCD to Investigate Her Client

Amid the new fecal matter that Mike Flynn lawyer Sidney Powell throws at Judge Emmet Sullivan in her sur-surreply purportedly asking for Brady material is a claim (ostensibly offered to support a claim that she’s entitled to his original notes even though she admits she has no proof to otherwise support her claim) that Peter Strzok was just too damned OCD to investigate her client.

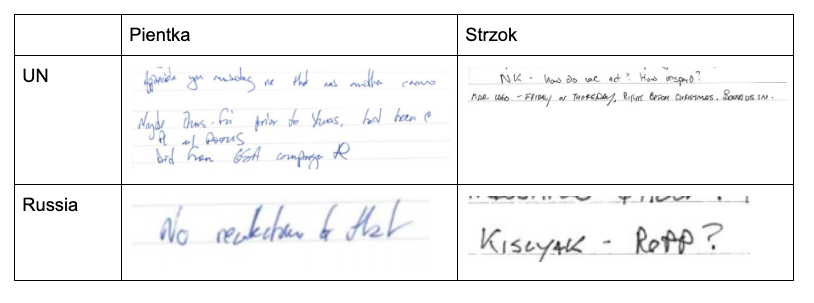

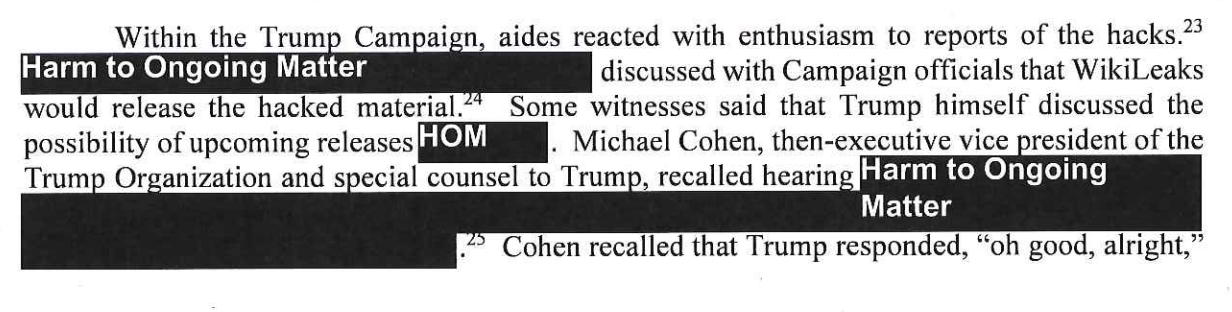

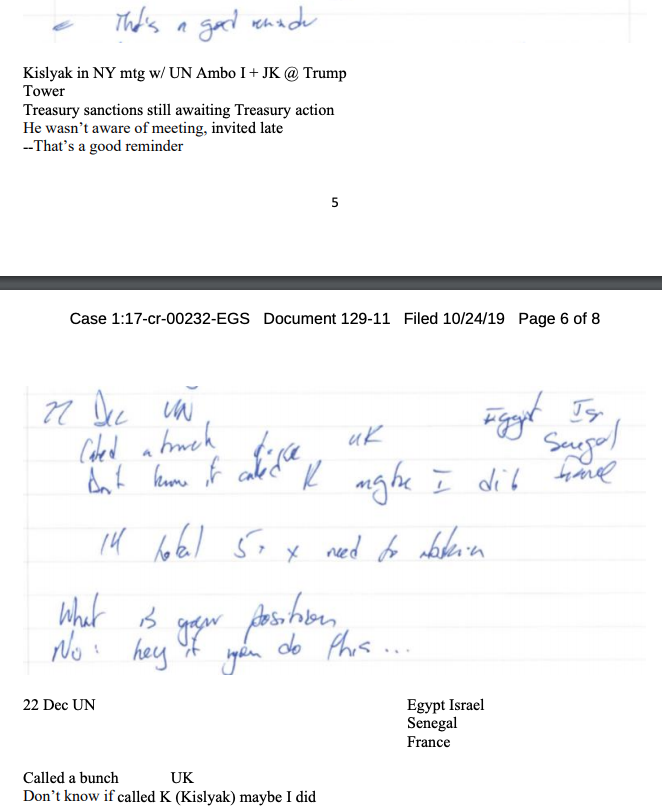

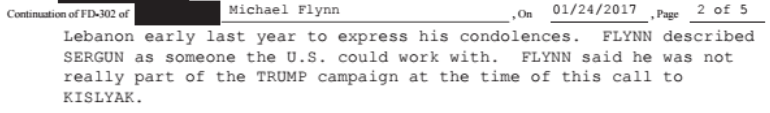

Moreover, even a layman can look at the two sets of notes and discern that Strzok’s miniscule, printed, within-the-lines, longer, and more detailed notes bear none of the hallmarks of being written during the press of an interview—much less by the secondary note-taker. That observation is even more obvious when compared with Agent 2’s notes, which do appear to be contemporaneous.

That’s not the most ridiculous thing in this latest brief, but given all the other complaints launched against Strzok in the last two years, that he operates too much “within-the-lines” is a dizzying plot twist.

Sidney Powell rewrites all of criminal procedure

The most ridiculous thing Powell does is — before she gets off the first page! — argue that the government has an obligation to comply with Brady before accepting a guilty plea or, barring that, must provide all Brady the day after he pleads.

The government’s Surreply is new only in its stunning admissions and untenable paradoxes. According to the government, it had no obligation to produce its superfluity of Brady evidence before Mr. Flynn pleaded guilty— because he was not a defendant until he was formally charged. And, it had no obligation to produce its cache after he pleaded guilty (the same or next day)—well . . . because his guilty plea erased its obligation.

If accepted, the government’s approach would allow endless manipulation by prosecutors: target individuals, run search warrants, seize devices, interrogate for days, threaten family members, cajole, but never charge until the clock strikes midnight once a plea is extracted. Yet playing cat-and-mouse with the Due Process Clause is the opposite of what the Brady-Bagley-Giglio line of cases is all about. Perhaps even more significantly, the government’s position wholly ignores this Court’s Standing Order, which not only has no such timing requirements, but is issued for the precise purpose of eliminating the games the government played here.

Even the most favorable reading of Emmet Sullivan’s standing order (the original one of which wasn’t filed until 5 days after the case got transferred to Sullivan on December 7, and the operative one of which wasn’t filed until 71 days after the case transfer, with five more days after that before the protective order first permitting the sharing of such information was filed) wouldn’t hold that the government has to turn over all Brady material within two days of pleading guilty before a judge who doesn’t have such a standing order.

It sure as hell doesn’t say the government has to disclose warrants to people under investigation or even that the government can only seize phones if they charge someone. I mean, that might be a nice world (or it might be a criminal hellhole), but that’s not the world she practices law in.

Mike Flynn is entitled to a Mulligan because he replaced his competent lawyer with a TV lawyer

Of course, there are problems.

One of which is that Flynn got everything anything normally considered Brady before he pled guilty for a second time before Sullivan. Powell deals with that in two ways. First, she suggests that everything that Flynn did under his previous counsel is reset when she came in as new counsel.

Nor was there “an extraordinary reversal” pursuant to which Mr. Flynn claims he is innocent. At no time did new, conflict-free counsel affirm the validity of Mr. Flynn’s guilty plea. In that same letter, counsel explained that “as was ingrained in [Mr. Flynn] from childhood,” he “took responsibility for what the SCO said he did wrong.”

On top of all the other things she’s demanding for her client, she’s also asking for a Mulligan.

Powell accuses Emmet Sullivan of just joking when asking Flynn about conflicts

Central to her ability to do so, of course, is the claim that Rob Kelner — whom the government described twice reviewed the issue with Flynn and waived any conflict — could not have waived that conflict. What’s awkward about all this is that (as the government noted in their filing), even without notice Sullivan raised it at Flynn’s last guilty plea.

Yet, he fails to respond to the point made in Mr. Flynn’s Reply that this conflict existed only because the government insisted not only on incessantly attacking Flynn’s FARA registration (beginning within weeks of its filing), but also on demanding its pairing with the completely unrelated White House interview prosecution. Simultaneously, the government did not even advert to the primary argument that the conflict was non-consentable, which meant that even if former counsel had fully disclosed and explained the risks associated with the conflict, Flynn could not agree to waive it. The Covington & Burling lawyers could not remain in the case. Most important of all, the government did not move to disqualify the lawyers or bring the matter to the attention of any court.

She returns to this later, suggesting that Sullivan could not know that Kelner might have a conflict when he invited Flynn to consult with other attorneys.

Mr. Van Grack unilaterally eliminated the possibility that the Court would learn enough to investigate further. He was content to allow hopelessly-conflicted counsel not merely to walk Mr. Flynn into five days of interviews with the Special Counsel team, but into an immediate, high-pressured plea of guilty without any demands for or production of Brady material, facilitated the waiver of countless rights, and signed an agreement for endless years of cooperation with the government at extraordinary personal expense. In addition to those benefits, the government was able to turn Mr. Flynn’s own counsel into the equivalent of adverse witnesses against him in the Rafiekian FARA case in the Eastern District of Virginia.

Note, Powell encouraged Kelner to expand his cooperation during the Kian trial in a bid to help sabotage it.

And then Powell claims that Flynn — who raised precisely the other claims she raises here (about impropriety leading up to his interview) — could not have known there was a problem.

The normal plea colloquy was insufficient to alert this Court to the problem, and Mr. Flynn did not know what Mr. Flynn did not know. When Mr. Flynn was asked if he was satisfied with the representation he was receiving, he had no way of knowing of the depths of the conflict of interest, and he had no way of knowing that some conflicts of interest are non-consentable. The prosecutors were more than just aware of this issue, they took full advantage of it. Their failure to address the issue in their Surreply concedes the non-consentable conflict. This is precisely why the government is required to focus the court’s attention to the issue by moving to disqualify counsel and thus letting the Court—not the government in cahoots with uber-conflicted counsel— persuade a defendant that he is getting advice from a safe source.

Effectively this is an insinuation that Sullivan, who bent over backwards to give Flynn the opportunity to ask for counsel from another lawyer, was too stupid to understand the potential need for Flynn to do so. Who knows? It could work. But pretending the Judge didn’t do precisely what you think should happen is not a good way to impress the Judge.

Powell renews the claim that her client was tricked into telling the lies he had already told

Only after asking for a Mulligan does Powell get around to reiterating her argument that mean FBI Agents ambushed her 30-year Intelligence veteran client into telling the same lies he had already told others at the White House. In doing so, she simply ignores what the government has already told her, including that they did not use the Steele dossier (which barely mentions Flynn) as a “pretext” to ask him why he was undermining the policy of the government.

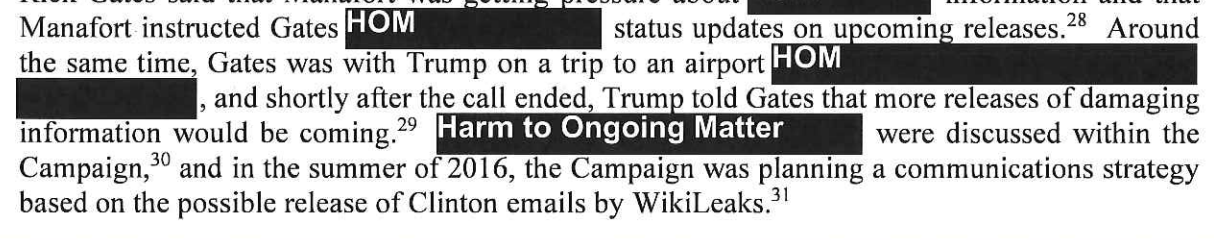

The government has known since prior to January 24, 2017, that it intended to target Mr. Flynn for federal prosecution. That is why the entire “investigation” of him was created at least as early as summer 2016 and pursued despite the absence of a legitimate basis. That is why Peter Strzok texted Lisa Page on January 10, 2017: “Sitting with Bill watching CNN. A TON more out. . . We’re discussing whether, now that this is out, we can use it as a pretext to go interview some people.” 3 The word “pretext” is key. Thinking he was communicating secretly only with his paramour before their illicit relationship and extreme bias were revealed to the world, Strzok let the cat out of the bag as to what the FBI was up to.

She then, bizarrely, provides proof that the FBI recognized right away that Flynn didn’t seem to be lying but his statements contradicted with everything that was on the transcript.

Former Deputy Director Andrew McCabe as much as admitted the FBI’s intent to set up Mr. Flynn on a criminal false statement charge from the get-go. On Dec. 19, 2017, McCabe told the House Intelligence Committee in sworn testimony: “[T]he conundrum that we faced on their return from the interview is that although [the agents] didn’t detect deception in the statements that he made in the interview . . . the statements were inconsistent with our understanding of the conversation that he had actually had with the ambassador.” McCabe proceeded to admit to the Committee that “the two people who interviewed [Flynn] didn’t think he was lying, [which] was not [a] great beginning of a false statement case.”

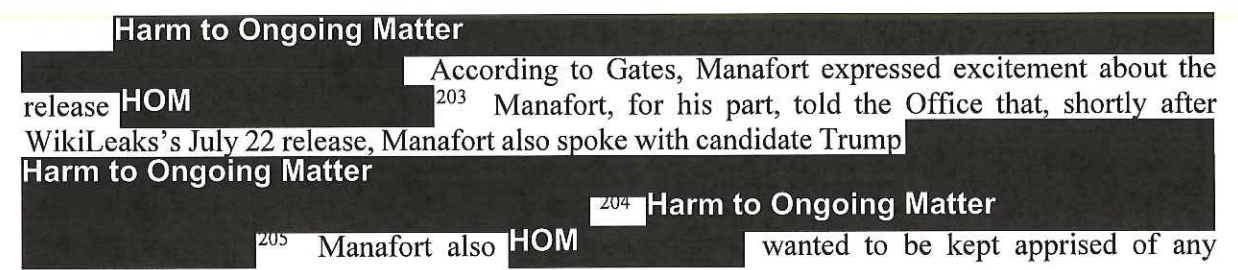

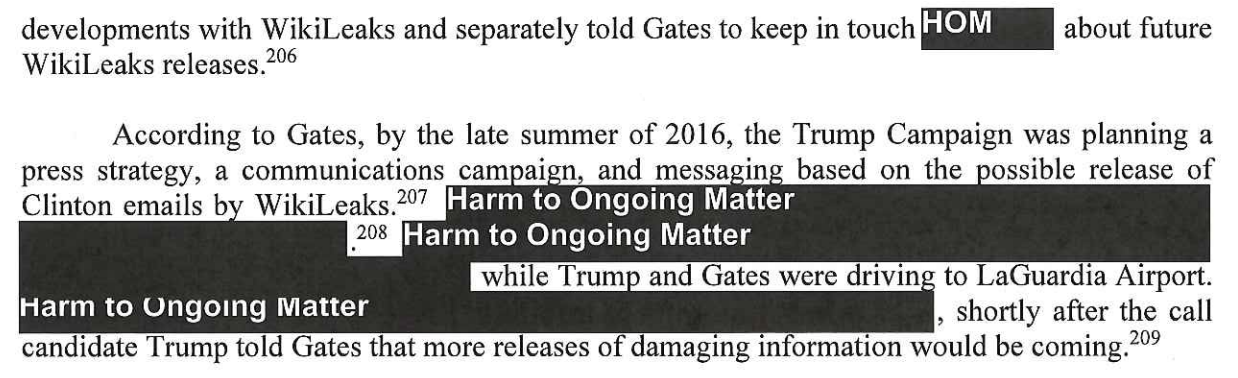

She then claims that when Brandon Van Grack said that nothing is in the government’s possession he instead said something else, then goes on to … I’m not sure what … without addressing the Van Grack point that the original agent notes match each other and every draft of the 302, meaning nothing in between would be different.

Tellingly, Mr. Van Grack does not deny that such information is, in fact, available.

The Strzok-Page text messages confirm that Lisa Page had two opportunities to edit drafts of the crucial 302. Strzok returned to his FBI office the night of February 10, 2017, to input the edits she made on the draft she had earlier left in Bill [Priestap’s] office (about which they hatch a cover-story), then sent her another version over the weekend. The government thus implicitly admits there was at least one version prior to the February 10 edition

(Note, with the last filing, the government provided three drafts of the 302, one of which was entered on January 24, meaning she already has this; she could mention that but it thoroughly undermines her own point.)

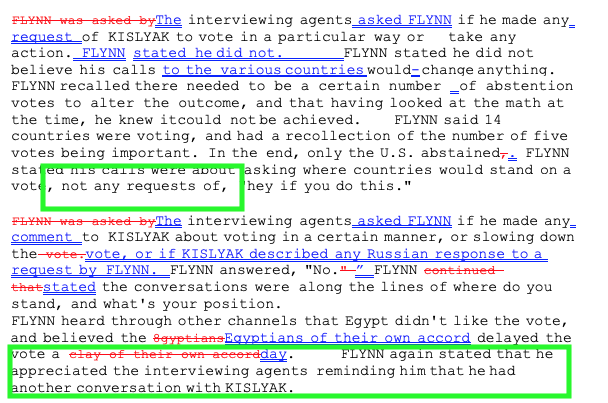

Finally, after making the claim that Strzok is too meticulous to investigate her client, she returns to a claim that I showed to be false, that the notes don’t support two of the false statements charges.

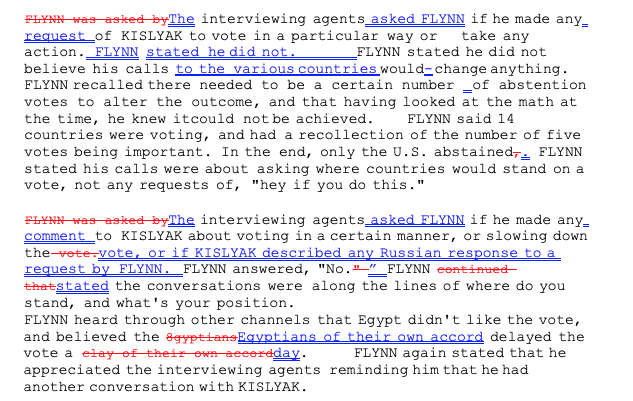

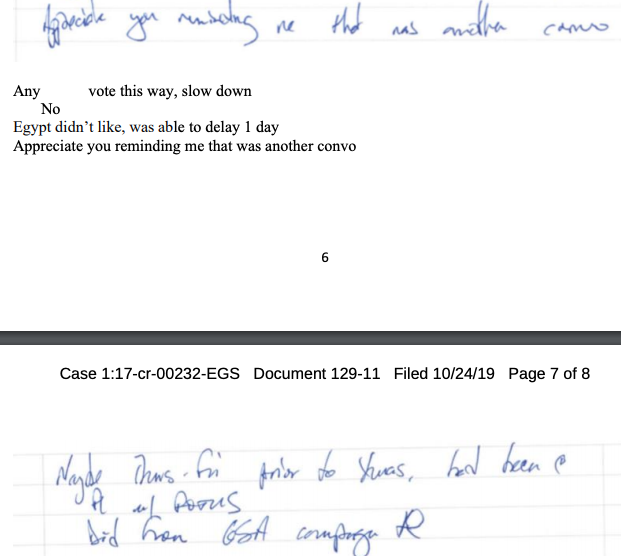

Read the notes of both agents for hours, and you won’t find a question or an answer about Kislyak’s response on either the UN vote or the sanctions—yet those assertions underpin the factual basis for the plea.

In about 30 minutes, however, one can find stuff in the notes that is consistent between the two and consistent with Flynn denying both cases.

Powell makes this harder to see, mind you, by doing a cut-and-paste job that splits notes on Flynn’s discussion of the UN calls. But it is there and in all the drafts.

Then she claims the redline, by adding a second denial from Flynn that he didn’t request Russia to act a certain way, somehow changes that it already included such a denial.

Previously, someone added an entire assertion untethered from either set of notes: “The interviewing agents asked FLYNN if he recalled any conversation with KISLYAK in which KISLYAK told him the Government of Russia had taken into account the incoming administration’s position about the expulsions, or where KISLYAK said the Government of Russia had responded, chosen to modulate their response, in any way to the U.S.’s actions as a result of a request by the incoming administration.” Although absent from the notes of both agents, this “Russian response” underpins the alleged crime.10

The government shows what I do: that the claims are in every 302. Including this one.

As note, the evidence Powell presents actually supports the government. But at least she refrained from accusing her client of lying this time.

Powell says prosecutors should never pursue plea deals

Then Powell argues that stuff that (again) happen with many criminal defendants shouldn’t happen with her own, such as that they enter into proffers.

The letter sent by the Special Counsel to Mr. Flynn’s then-counsel, Covington & Burling, before the proffer interviews made clear that, “by receiving [Mr. Flynn’s] proffer, the government does not agree to make any motion on [his] behalf or to enter into a cooperation agreement, plea agreement, immunity agreement or non- prosecution agreement with Client.” Although the letter made a general promise not to use statements made in the interviews against Mr. Flynn, the promise included an important final clause: “Should Client be prosecuted, no statements made by Client during the meeting will be used against Client in the government’s case-in-chief at trial or for purposes of sentencing, except as provided below.” (emphasis added). The listed exceptions render the “promise” a practical nullity.

It is disingenuous to suggest that the proffer sessions were not adversarial when the government had permission to target Mr. Flynn, seized all his electronic devices, targeted his son, and seized his son’s devices. The government fails to mention that, to obtain the plea, it threatened Mr. Flynn with indictment the next day, the indictment of his son who had a new baby, promised him “the Manafort treatment,” and promised to pile on charges sufficient to put him in prison the rest of his life. The short fuse was no doubt motivated by the government’s knowledge, which it did not disclose to Flynn, that the salacious Strzok-Page emails, disclosing their vitriolic hatred of President Trump and his team, the key agents’ affair, and their termination from Mueller’s Special Counsel operation were going to be exposed the very next day. No individual, no matter how innocent, can withstand such pressure, particularly when represented by conflicted defense counsel. The advice a client is given by his lawyer in such fraught circumstances can make all the difference between standing his ground or caving to the immense pressure. Mr. Flynn caved, not because he is guilty, but because of the government’s failure to put its cards on the table, as Brady, requires, and its failure to ensure that Mr. Flynn was represented by un-conflicted counsel when he was forced to make that decision.

I mean, you sort of have to pick. Is your client a sophisticated intelligence officer with 30 years experience, or is he — represented by a very good lawyer — weaker than other similarly situated people? What Powell lays out, however, is not proof that he was treated differently, but actually proof he was treated the same, however shitty our prosecutorial practices are.

Powell admits she pulled a bait-and-switch but promises to return to it

Finally, there’s the matter of Powell’s bait-and-switch, her late demand to have the plea thrown out in the middle of a specious Brady request. As I noted, prosecutors were a little coy, suggesting that until she presents the demand as a lawyer would, with actual case law, they can only assume she’s arguing a Brady problem.

The most interesting (and potentially risky): even though Sullivan ordered them to address “the new relief, claims, arguments, and information” raised in Powell’s “reply,” they still treat this as primarily a question of Brady obligations. In addressing Powell’s demand to have the prosecution thrown out, they play dumb, noting that Powell has not presented her demand as a lawyer would, with citations and case law, and so then make an assumption that this is primarily about Brady.

In his Reply, the defendant also seeks a new category of relief, that “this Court . . . dismiss the entire prosecution for outrageous government misconduct.” Reply at 32; see also id. at 3 (“dismiss the entire prosecution based on the outrageous and un-American conduct of law enforcement officials and the subsequent failure of the prosecution to disclose this evidence . . . in a timely fashion or at all”). The defendant does not state under what federal or local rule he is seeking such relief, or cite to relevant case law.9 In order to provide a response, the government presumes, given the context in which this request for relief arose, that the defendant is seeking dismissal as a remedy or sanction for a purported failure to comply with Brady and/or this Court’s Standing Order.

9 Local Criminal Rule 47(a) specifically requires that “[e]ach motion shall include or be accompanied by a statement of the specific points of law and authority that support the motion, including where appropriate a concise statement of the facts” (emphasis added). The defendant now seeks relief from this Court for claims that he has not properly raised; the government is hampered in its ability to accurately respond to the defendant’s argument because he has failed to state the specific points of law and authority that support his motion.

I’m sure Powell’s response will be “Ted Stevens Ted Stevens Ted Stevens.” But even if it is, that’s something she could have cited in her new demand for relief and did not.

They do go on to address the claim that the FBI engaged in outrageous behavior, focusing relentlessly on the January 24 interview, rather than Powell’s more far-flung conspiracy theories. But ultimately, this seems to be an attempt to do what they tried to do when they first alerted Emmet Sullivan that Powell had raised new issues, to either force her to submit her demand to have the whole prosecution thrown out as a separate motion, or to substantiate her Brady claims.

When complaining that the government didn’t reply to her demand, she doesn’t address the fact that she hasn’t cited any law to support her.

As predicted, she instead cites Ted Stevens.

The government sought and received permission to file a Surreply by complaining that the defendant had bootlegged “new” arguments into his Reply. Yet its Surreply either elides the supposedly new material altogether or does not address it in terms.

[snip]

Rather, as a matter of procedure, counsel advised the Court that we anticipated seeking dismissal rather than withdrawal. Nothing we have found in the law requires a defendant to withdraw his guilty plea rather than seek dismissal for egregious government misconduct. Analogously, this Court did not have to grant a new trial to Ted Stevens before it could dismiss the entire prosecution in the interest of justice.

But it looks like the government gamble paid off. After bitching at the government for ignoring her bait-and-switch, at the very end of the brief, she says that she will formally ask for something she spent a good chunk of her last filing arguing for now and pretends that this is all just a Brady request.

In conclusion, yes, the government engaged in conduct so shocking to the conscience and so inimical to our system of justice that it requires the dismissal of the charges for outrageous government conduct. See United States v. Russell, 411 U.S. 423, 428 (1973). However, as fully briefed in our Motion to Compel and Reply, at this time, Mr. Flynn only requests an order compelling the government to produce the additional Brady evidence he has requested—in full and unredacted form—and an order to show cause why the government should not be held in contempt. At the appropriate time, Mr. Flynn will file a separate motion asking that the Court dismiss the prosecution for egregious government misconduct and in the interest of justice. Mr. Flynn is entitled to discovery of the materials he has requested in these motions and briefs that will help him support such a motion.

At some point, this bait-and-switch is bound to piss off Judge Sullivan, who now has to read two more briefs because of Powell’s little ploy. And I’m not sure invoking the ghost of Ted Stevens will be enough to mitigate any risk of pissing him off about this.