In the middle of a motion in limine arguing, in part, that the Durham prosecutors should be able to introduce two sets of emails from Sergei Millian to one of the journalists who gave Igor Danchenko Millian’s contact information, John Durham admits that those emails are the most probative evidence he’s got that Millian never met or spoke with Danchenko.

Fourth, whether the statements are the most probative evidence on the point. Millian’s emails written contemporaneous to the events at issue are undoubtedly the most probative evidence to support the fact that Millian had never met or spoken with the defendant.

Mind you, whether Millian ever spoke to Danchenko or not is irrelevant to whether Danchenko believed that he had.

But Durham appears not to understand that.

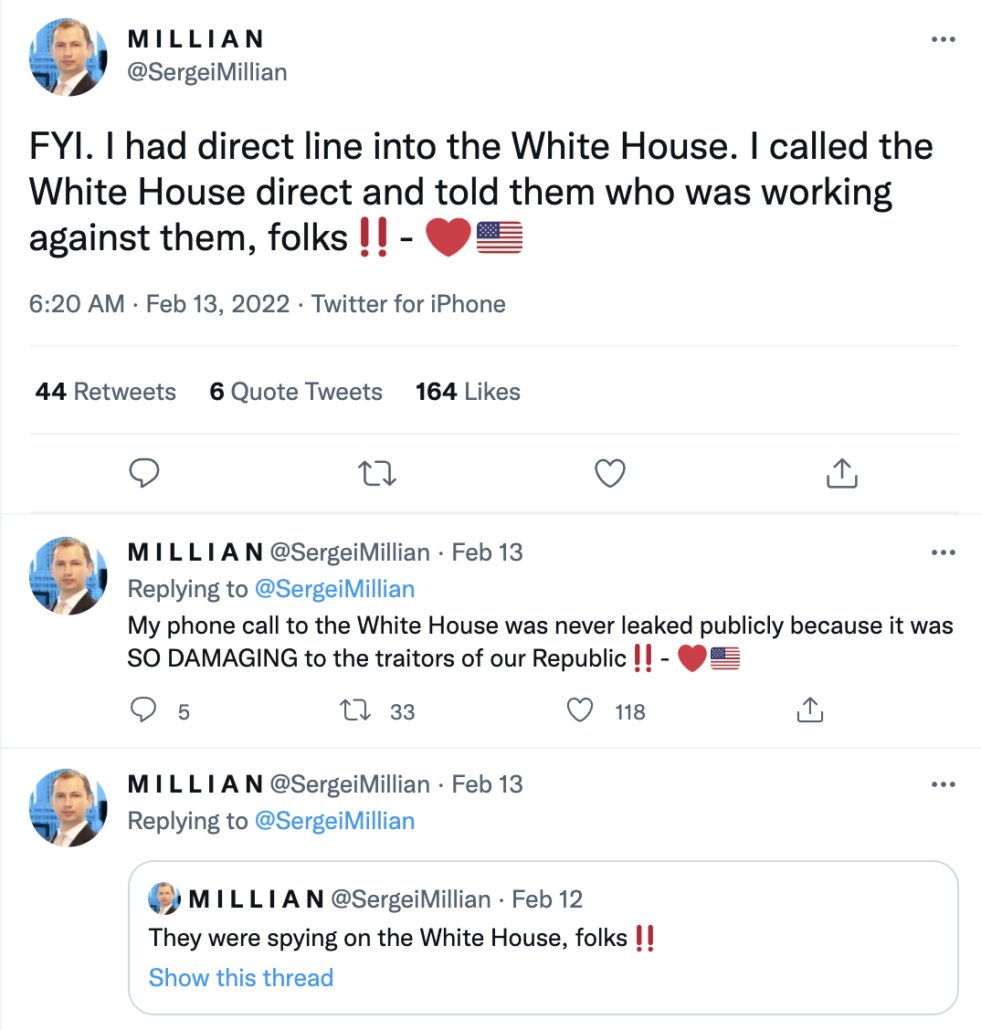

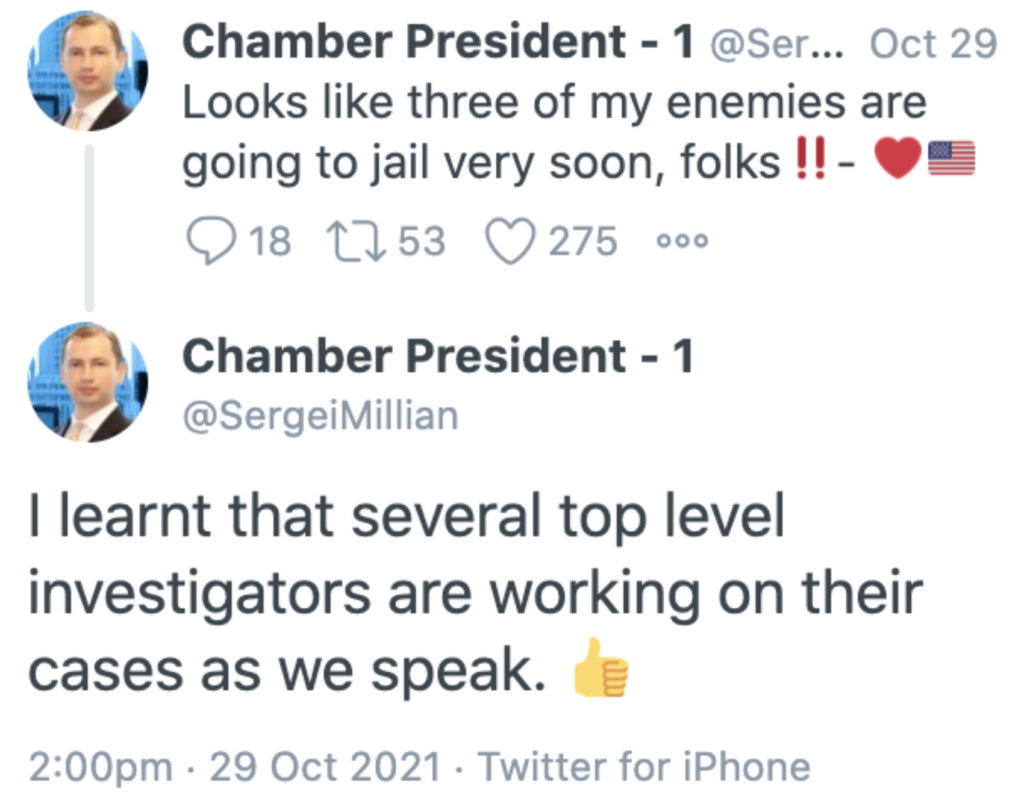

If you don’t mind, I think I’ll punctuate this post with stupid Millian Tweets — like some Greek chorus — while I take breaks to wrap my brain around how Durham got his ass so badly handed to him by Sergei Millian.

Durham appears not to understand that if Danchenko got a phone call from someone else in July 2016, but believed at the time that the call was from Millian, then his four charged statements that he believed the call was from Millian would still be entirely true — an argument I made last year and one Danchenko made in his Motion to Dismiss (Danchenko’s MTD was filed after the government motion, but submitted unsealed from the start).

[T]he indictment does not allege that Mr. Danchenko did not receive an anonymous phone call in or about late July 2016. Instead, the indictment alleges only that Mr. Danchenko “never received such a phone call or information from any person he believed to be Chamber President-1[.]” The alleged false statement is that Danchenko did not truly believe that the anonymous caller was Chamber President-1. The indictment also alleges that Mr. Danchenko “never made any arrangements to meet Chamber President-1.” However, Mr. Danchenko never stated that he made such arrangements. Rather, he told the FBI that he arranged to meet the anonymous caller, but the anonymous caller never showed up for the meeting.

But Durham believes his job is to prove that Millian never spoke with Danchenko, and so spent a third of his filing making humiliating admissions about how weak his case is.

One of the dire problems Durham has with his Millian case is that … as I predicted … he has no witness.

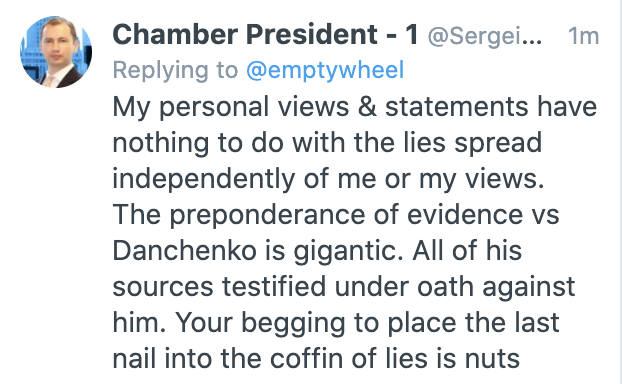

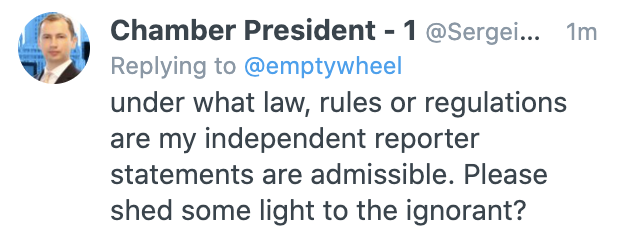

As I noted last year, when he originally charged Danchenko, he relied on Millian’s Twitter feed, not an interview with Millian, to substantiate Millian’s claim that he never spoke with Danchenko. Here’s how Sergei responded last year when I pointed out that his testimony, under oath, would be necessary to convict Danchenko.

Turns out I wasn’t nuts. All of the sources against Danchenko were willing to testify under oath, it appears, but Millian. Well, and Christopher Steele, too, but that’s for another post.

To Durham’s … um … credit, he did at some point (he tellingly hides the date) get Millian to participate in a “virtual interview” (which may or may not be the same as a “video interview”?). In that interview, Millian claimed that rather than fleeing the US because of the criminal investigation into him and Mueller’s interest in interviewing him, he fled the country because of the Steele dossier.

The Government has conducted a virtual interview of Millian. Based on representations from counsel, the Government believes that Millian was located in Dubai at the time of the interview. During the interview, Millian stated, in sum and substance, that he has never met with or spoken with the defendant, Millian informed investigators that he left the United States in March 2017 and he has not returned. Millian stated, in sum, that he left the United States due to threats on his and his family’s personal safety because of his alleged role in the Steele Reports. On multiple occasions, the Government has inquired about Millian’s availability to testify at the defendant’s trial. Millian has repeatedly informed the Government that he has concerns for his and his family’s safety (who reside abroad) should he testify. Millian also informed the Government that he does not trust the FBI and fears being arrested if he returns to the United States. The Government has repeatedly informed Millian that it will work to ensure his security during his time in the United States, as it does with all witnesses. The Government has also been in contact with Millian’s counsel about the possibility of his testimony at trial. Nonetheless, despite its best efforts, the Government’s attempts to secure Millian’s voluntary testimony have been unsuccessful. Moreover, counsel for Millian would not accept service of a trial subpoena and advised that he does not know Millian’s address in order to effect service abroad.

Durham was unable to subpoena Millian to require him to testify under oath to his claim that he never spoke with Danchenko, because Sergei’s lawyer doesn’t know where he lives, not even to bill him. I guess he bills him “virtually,” just like the interviews.

But don’t worry. Durham promises he has other evidence that Sergei could not have called Danchenko in July 2016.

That evidence is that Millian was traveling in Asia during the period between July 21 and July 26, 2016, when such a call to Danchenko would have taken place.

Millian was traveling in Asia at the time the defendant sent this email and did not return to New York until late on the night of July 27, 2016. Notably, Millian had suspended his cellular phone service effective July 14, 2016 (prior to his travel) and his service was reconnected effective August 8, 2016. The defendant did travel to New York from July 26, 2016 through July 28, 2016 with his young daughter and spent much of his time sight-seeing, including a trip to the Bronx Zoo on July 28, 2016. The defendant would later claim to the FBI that it was during this trip to New York that the defendant attempted to meet Sergei Millian (after having received the alleged anonymous phone call from a person he purportedly believed to be Millian). [my emphasis]

The implication, says the Special Counsel who flew to Italy to get the multiple phones of Joseph Mifsud but who never walked across DOJ to get the multiple phones of his key witness Jim Baker, is that Millian could not have called Danchenko because the only possible SIM card he would have used while traveling in Asia, which generally used the GSM standard, would be the phone he used in the US, where CDMA was still widely used.

Millian couldn’t have called Danchenko during the period, Durham says, because his US-based phone was shut down while he was traveling in Asia.

That would be a shocking claim to make about any fairly sophisticated traveler in 2016, much less one who made the effort to shut off his location tracker cell coverage while he traveled overseas and for twelve days after he returned.

It’s an especially remarkable claim to make about someone that — DOJ has proof! — was arranging in-person meetings in NYC in precisely the same period, via text messages sent during the period when Millian’s US phone service was shut down.

Papadopoulos first connected with Millian via Linkedln on July 15, 2016, shortly after Papadopoulos had attended the TAG Summit with Clovis.500 Millian, an American citizen who is a native of Belarus, introduced himself “as president of [the] New York-based Russian American Chamber of Commerce,” and claimed that through that position he had ” insider knowledge and direct access to the top hierarchy in Russian politics.”501 Papadopoulos asked Timofeev whether he had heard of Millian.502 Although Timofeev said no,503 Papadopoulos met Millian in New York City.504 The meetings took place on July 30 and August 1, 2016.505 Afterwards, Millian invited Papadopoulos to attend-and potentially speak at-two international energy conferences, including one that was to be held in Moscow in September 2016.506 Papadopoulos ultimately did not attend either conference.

500 7/15/16 Linkedln Message, Millian to Papadopoulos.

501 7 /15/16 Linkedln Message, Millian to Papadopoulos.

502 7/22/16 Facebook Message, Papadopoulos to Timofeev (7:40:23 p.m.); 7/26/16 Facebook Message, Papadopoulos to Timofeev (3:08:57 p.m.).

503 7/23/16 Facebook Message, Timofeev to Papadopoulos (4:31:37 a.m.); 7/26/16 Facebook Message, Timofeev to Papadopoulos (3:37: 16 p.m.).

504 7/16/16 Text Messages, Papadopoulos & Millian (7:55:43 p.m.).

505 7/30/16 Text Messages, Papadopoulos & Millian (5:38 & 6:05 p.m.); 7/31/16 Text Messages, Millian & Papadopoulos (3:48 & 4:18 p.m.); 8/ 1/16 Text Message, Millian to Papadopoulos (8:19 p.m.).

506 8/2/16 Text Messages, Millian & Papadopoulos (3 :04 & 3 :05 p.m.); 8/3/16 Facebook Messages, Papadopoulos & Millian (4:07:37 a.m. & 1:11:58 p.m.).

Anyway, that’s the background to why, Durham says, the best evidence he’s got that Millian never called Danchenko are some emails.

One of those emails is inconsistent with Durham’s story, which says that Millian returned late on July 27, which was a Wednesday. On July 26, Millian sent this to one of the RIA Novosti journalists, Dimitry Zlodorev:

Dimitry, on Friday I’m returning from Asia. An email came from Igor. Who is that? What sort of person?

Durham says one of his best pieces of evidence that Millian didn’t call Danchenko is an email that had him returning two days later than he actually returned. Something led Millian to come back early, at least according to Durham’s record.

Early enough to be in NYC when Danchenko was there.

Durham also wants to introduce some emails Millian sent Zlodorev in 2020, three years after Danchenko’s alleged lie and four years into a manufactured outrage over the Steele dossier. One of those emails suggests that Millian believed Steele blamed Danchenko for problems with the dossier, which is probably true, but Durham thinks it helps him anyway.

I’ve been informed that Bogdanovsky travelled to New York with Danchenko at the end of July 2016; Danchenko, supposedly to meet with me (but the meeting didn’t take place). Can you inquire with Bogdanovsky whether he remembers something from that trip and whether they touched upon my name in conversation, as well as for what reason Danchenko was travelling to NY? Steele, it seems, made Danchenko the fall guy, but Danchenko himself made several statements that were difficult to understand, for example, about the call with me. Did he tell Bogdanovsky that he communicated with me by phone and on what topic? Thank you! This will clarify a lot for me personally. It’s a convoluted story! [my emphasis]

That’s how desperate he is for evidence to prove his four Millian charges.

Now, as Durham did when he tried to introduce totally unrelated emails in the Michael Sussmann case, Durham says he’s not introducing these (as what he calls “the most probative evidence” that Millian didn’t call Danchenko) for the truth.

He’s just asking questions — but not, apparently, why Millian said he was coming back Friday when he ended up coming back on Wednesday instead, early enough to be in NY when Danchenko was there.

As an initial matter, all three emails to Zlodorev are admissible non-hearsay because each email consists of a series of questions, i.e., (1) “Who is that? What sort of person?” (July 26, 2016), (2) “Do you remember such a person? Igor Danchenko?” (July 19, 2020), and (3) (a) “Can you inquire with Bogdanovsky whether he remembers something from that trip and whether they touched upon my name in conversation, as well as for what reason Danchenko was travelling to NY? (b) “Did he tell Bogdanovsky that he communicated with me by phone and on what topic?” (July 20, 2020). See Sinclair, F. App’x at 253. To the extent the remaining sentences in those emails are statements, they are not being offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. Indeed, with respect to the July 26, 2016 email, the Government is not seeking to prove that (1) Millian was returning from Asia on Friday or (2) that an email came from the defendant.

And if his just asking questions ploy doesn’t work, then he’ll raise the point that he charged this indictment without ever talking to Sergei Millian first!!!

First, the unavailability of the declarant. A declarant is “unavailable” at a hearing or trial when he “is absent from the hearing and the proponent of a statement has not been able, by process or other reasonable means, to procure the declarant’s attendance or testimony. Fed. R. Evid. 804(a)(5)(B). “Courts have consistently held that hearsay exceptions premised on the unavailability of a witness require the proponent of a statement to show a good faith, genuine, and bona fide effort to procure a witness’s attendance.” United States v. Wrenn, 170 F. Supp. 2d 604, 607 (E.D. Va. 2001) (citing Barber v. Page., 390 U.S. 719,724 (1968)). Courts considering whether a prosecutor, as the proponent of a statement, “has made such a good faith effort have focused on the reasonableness of the prosecutor’s efforts.” Id. \ Ohio v. Roberts, 448 U.S. 56, 74 (1980) (“The lengths to which the prosecutor must go to produce a witness … is a question of reasonableness. The ultimate question is whether the witness is unavailable despite good-faith efforts undertaken prior to trial to locate and present the witness.”). In the case of a U.S. national residing in a foreign country, 28 U.S.C. § 1783 allows for the service of a subpoena on a U.S. national residing abroad. Here, the Government has made substantial and repeated efforts to secure Millian’s voluntary testimony. When those efforts failed, the Government attempted to serve a subpoena on Millian’s counsel who advised that he was not authorized to accept service on behalf of Mr. Millian. The Government, not being aware of Millian’s exact location or address, asked counsel to provide Millian’s address so that service of a subpoena could be effectuated pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1783. Counsel stated that he does not know Millian’s address. In any event, even if the Government had been able to locate Millian, it appears unlikely that Millian would comply with the subpoena and travel to the United States to testify. Indeed, as discussed above, Millian has shown a reluctance to travel to the United States for fear of his personal safety and his family’s safety. Accordingly, the Government has demonstrated good faith efforts to secure Millian’s appearance at trial.

What’s interesting is that Durham not only claims that Millian had no motive to lie to Zlodorev in 2016, but he asserts that “the existence of the Steele Reports were not public.”

The Government is not aware of any evidence that Millian was aware of who the defendant was in July of 2016. Millian also had no motive to lie about his knowledge of the defendant in July 2016. Indeed, at that time of the July 2016 email the existence of the Steele Reports were not public. Further, Millian had no apparent motive to lie to Zlodorev, an individual he appears to consider a friend.

They were to this guy.

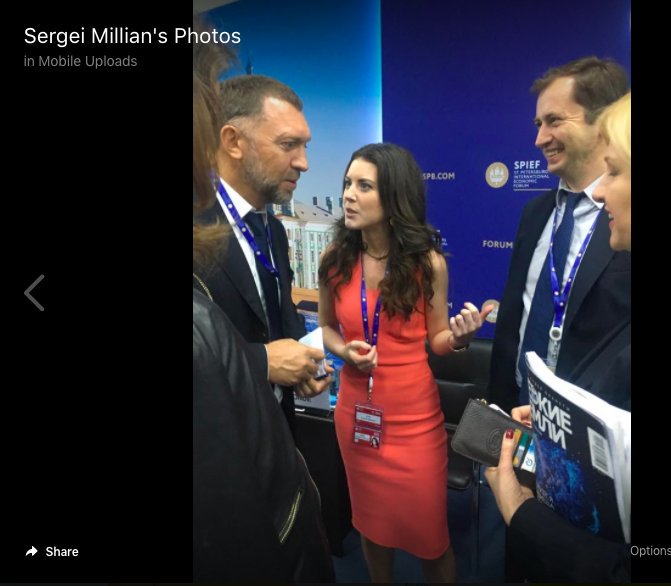

According to the IG Report that Durham had never read before charging Sussmann, an Oleg Deripaska associate likely knew of the dossier by early July 2016, weeks after Millian met with one of the key architects of the 2016 operation in St. Petersburg and weeks before Danchenko emailed Millian and then Millian grilled Zlodorev about who Danchenko was.

Oleg Deripaska had a motive to lie about the dossier — and he appears to have been lying, to both sides.

Similarly, Durham claims that Millian had no motive to lie in 2020 when he grilled Zlodorev again about the circumstances of his meeting with Danchenko.

The July 2020 emails between Millian and Zlodorev also bear circumstantial guarantees of trustworthiness. Again, in July 2020, Millian had no motive to lie to Zlodorev.

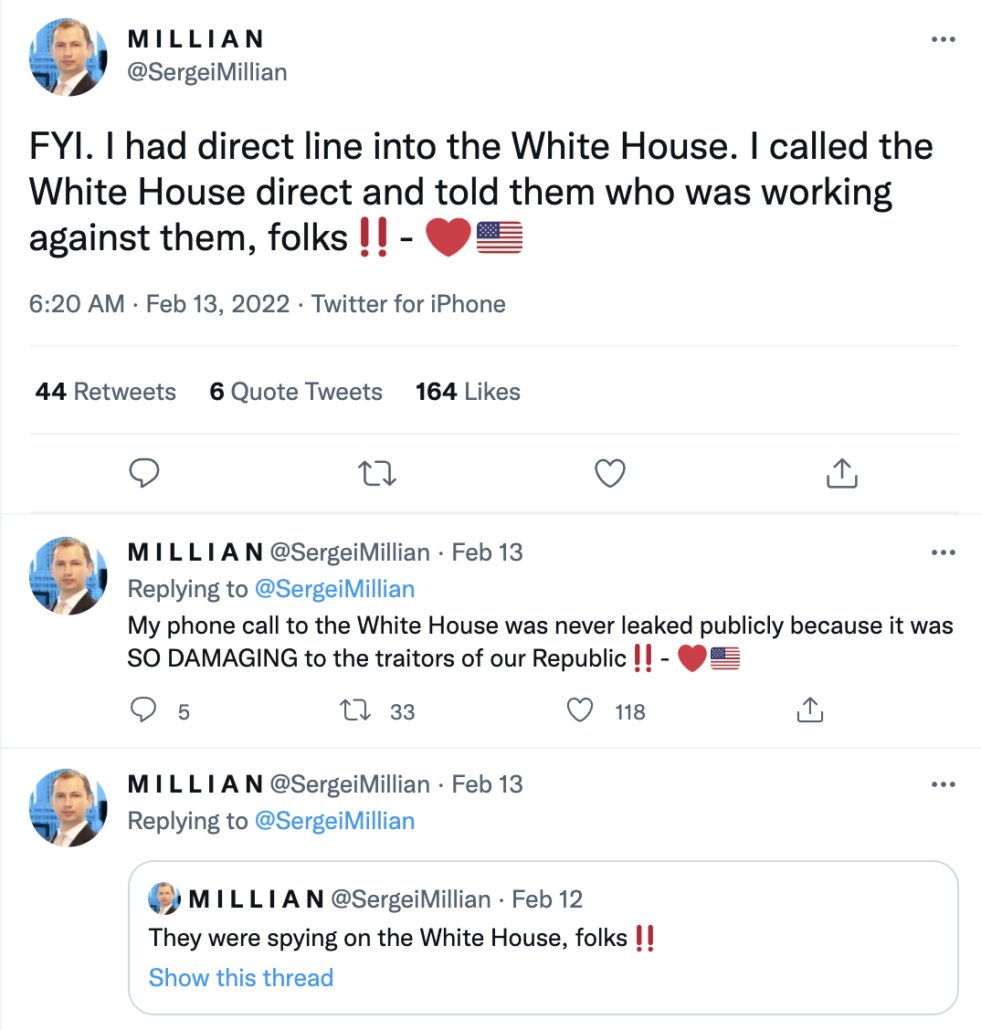

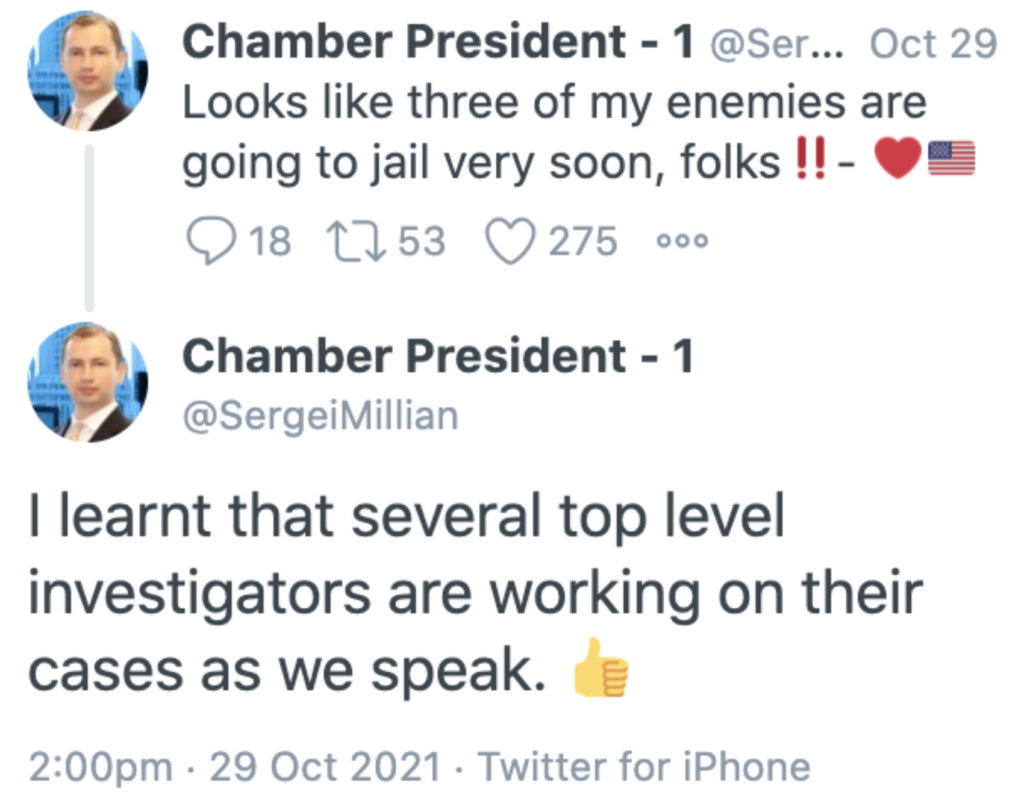

Which is really nutty, because the Twitter account that Durham relied on to charge this thing claimed that — years earlier and therefore presumably well before 2020 — he had personally called the White House and told them the identities of the people behind the dossier.

He would have called from Asia or some other undisclosed location, though, so in Durham’s mind such a call would not exist.

And that’s how it came about that we’re a month away from trial, and John Durham is begging Anthony Trenga to admit emails from 2020 as his best evidence in four charges against Danchenko because he decided to rely on a Twitter account rather than securing witnesses in his case first.

For months and years, John Durham has treated Sergei Millian — a man who fled the country to avoid a counterintelligence investigation and questions from Mueller, but whom Durham claims fled the country because of the dossier — as an aggrieved victim. And in the same filing admitting that he has no solid evidence to prove that he is a victim, Durham also talked about how important it is to consider whether you’re getting played by Russian disinformation.

Such evidence is admissible because in any investigation of potential collusion between the Russian Government and a political campaign, it is appropriate and necessary for the FBI to consider whether information it receives via foreign nationals may be a product of Russian intelligence efforts or disinformation.

“SCO Durham, think of your legacy please❗❗”

Update: Replaced “in real time” based on Just Some Guy’s observations.

Earlier emptywheel coverage of the Danchenko case

The Igor Danchenko Indictment: Structure

John Durham May Have Made Igor Danchenko “Aggrieved” Under FISA

“Yes and No:” John Durham Confuses Networking with Intelligence Collection

Daisy-Chain: The FBI Appears to Have Asked Danchenko Whether Dolan Was a Source for Steele, Not Danchenko

Source 6A: John Durham’s Twitter Charges

John Durham: Destroying the Purported Victims to Save Them

John Durham’s Cut-and-Paste Failures — and Other Indices of Unreliability

Aleksej Gubarev Drops Lawsuit after DOJ Confirms Steele Dossier Report Naming Gubarev’s Company Came from His Employee

In Story Purporting to “Reckon” with Steele’s Baseless Insinuations, CNN Spreads Durham’s Unsubstantiated Insinuations

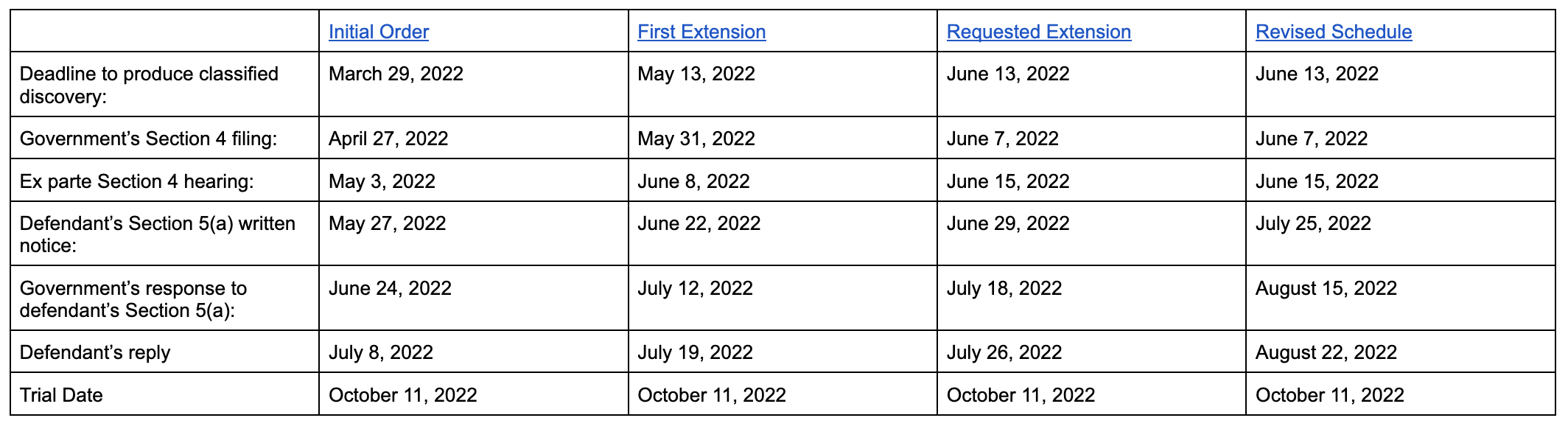

On CIPA and Sequestration: Durham’s Discovery Deadends

The Disinformation that Got Told: Michael Cohen Was, in Fact, Hiding Secret Communications with the Kremlin

John Durham’s Igor Danchenko Case May Be More Problematic than His Michael Sussmann Case

“Desperate at Best:” Igor Danchenko Starts Dismantling John Durham’s Case against Him