In this series, I have been showing a framework for the investigation that the Mueller questions, as imagined by Jay Sekulow, maps out. Thus far I have shown:

- Russians, led by the Aras Agalarov and his son, cultivated Trump for years by dangling two things: real estate deals and close ties with Vladimir Putin.

- During the election, the Russians and Trump appear to have danced towards a quid pro quo agreement, with the Russians offering dirt on Hillary Clinton in exchange for a commitment to sanctions relief, with some policy considerations thrown in.

- During the transition period, Trump’s team took a series of actions that moved towards consummating the deal they had made with Russia, both in terms of policy concessions, particularly sanctions relief, and funding from Russian sources that could only be tapped if sanctions were lifted. The Trump team took measures to keep those actions secret.

- Starting in January 2017, Trump came to learn that FBI was investigating Mike Flynn. His real reasons for firing Flynn remain unreported, but it appears he had some concerns that the investigation into Flynn would expose him.

This post lays out the questions on obstruction that lead up to Comey’s firing on May 9, 2017.

February 14, 2017: What was the purpose of your Feb. 14, 2017, meeting with Mr. Comey, and what was said?

On February 13, Trump fired Mike Flynn. The explanation he gave was one of the concerns Sally Yates had given to Don McGahn when she told him about the interview, that Flynn had lied to Mike Pence about having discussed sanctions relief with Sergey Kislyak on December 29, 2016. Except, coming from Trump, that excuse makes no sense, both because he had already shown he didn’t care about the counterintelligence implications of that lie by including Flynn in the January 28 phone call with Putin and other sensitive meetings. But also because at least seven people in the White House knew what occurred in Flynn’s calls, and Pence probably did too.

Against that backdrop, the next day, Trump had Jim Comey stay late after an oval office meeting so he could ask him to drop the investigation into Flynn. Leading up to this meeting, Trump had already:

- Asked Comey to investigate the pee tape allegations so he could exonerate the President

- Asked if FBI leaks

- Asked if Comey was loyal shortly after asking him, for the third time, if he wanted to keep his job

- Claimed he distrusted Flynn’s judgment because he had delayed telling Trump about a congratulatory call from Putin

After Trump asked everyone in the meeting to leave him and Comey alone, both Jeff Sessions and Jared Kushner lingered.

While the description of this meeting usually focuses on the Flynn discussion, according to Comey’s discussion, it also focused closely on leaks, which shows how Trump linked the two in his mind.

Here’s what Comey claims Trump said about Flynn:

He began by saying he wanted to “talk about Mike Flynn.” He then said that, although Flynn “hadn’t done anything wrong” in his call with the Russians (a point he made at least two more times in the conversation), he had to let him go because he misled the Vice President, whom he described as “a good guy.” He explained that he just couldn’t have Flynn misleading the vice President and, in any event, he had other concerns about Flynn, and had a great guy coming in, so he had to let Flynn go.

[a discussion of Sean Spicer’s presser explaining the firing and another about the leaks of his calls to Mexican and Australian leaders]

He then referred at length to the leaks relating to Mike Flynn’s call with the Russians, which he stressed was not wrong in any way (“he made lots of calls”), but that the leaks were terrible.

[Comey’s agreement with Trump about the problem with leaks, but also his explanation that the leaks may not have been FBI; Reince Priebus tries to interrupt but Trump sends him away for a minute or two]

He then returned to the topic of Mike Flynn, saying that Flynn is a good guy, and has been through a lot. He misled the Vice President but he didn’t do anything wrong on the call. He said, “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go. He is a good guy. I hope you can let this go.” I replied by saying, “I agree he is a good guy,” but said no more.

In addition to providing Trump an opportunity to rebut Comey, asking this question might aim to understand the real reason Trump fired Flynn.

March 2, 2017: What did you think and do regarding the recusal of Mr. Sessions? What efforts did you make to try to get him to change his mind? Did you discuss whether Mr. Sessions would protect you, and reference past attorneys general?

On March 2, citing consultations with senior department officials, Sessions recused himself “from any existing or future investigations of any matters related in any way to the campaigns for President of the United States,” while noting that, “This announcement should not be interpreted as confirmation of the existence of any investigation or suggestive of the scope of any such investigation.” At that point, Dana Boente became Acting Attorney General for the investigation.

Note that this question isn’t just about Trump’s response to Sessions’ recusal — it’s also about what he did in advance of it. That’s likely because even before Sessions recused, Trump got Don McGahn to try to pressure the Attorney General not to do so. He also called Comey the night before and “talked about Sessions a bit.” When Sessions ultimately did recuse, Trump had a blow-up in which he expressed a belief that Attorneys General should protect their president.

[T]he president erupted in anger in front of numerous White House officials, saying he needed his attorney general to protect him. Mr. Trump said he had expected his top law enforcement official to safeguard him the way he believed Robert F. Kennedy, as attorney general, had done for his brother John F. Kennedy and Eric H. Holder Jr. had for Barack Obama.

Mr. Trump then asked, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?”

In the days after the Sessions recusal, Trump also kicked off the year-long panic about being wiretapped.

On Thursday, Jeff Sessions recused from the election-related parts of this investigation. In response, Trump went on a rant (inside the White House) reported to be as angry as any since he became President. The next morning, Trump responded to a Breitbart article alleging a coup by making accusations that suggest any wiretaps involved in this investigation would be improper. Having reframed wiretaps that would be targeted at Russian spies as illegitimate, Trump then invited Nunes to explore any surveillance of campaign officials, even that not directly tied to Trump himself.

And Nunes obliged.

Don McGahn and Jeff Sessions, among others, have already provided their side of this story to Mueller’s team.

March 2 to March 20, 2017: What did you know about the F.B.I.’s investigation into Mr. Flynn and Russia in the days leading up to Mr. Comey’s testimony on March 20, 2017?

As Sekulow has recorded Mueller’s question, the special counsel wants to know what Trump already knew of the investigation into Mike Flynn before Comey publicly confirmed it in Congressional testimony. This may be a baseline question, to measure how much of Trump’s response was a reaction to the investigation becoming public.

But there are other things that went down in the weeks leading up to Comey’s testimony. Devin Nunes had already made considerable efforts to undermine the investigation; he would have been briefed on the investigation on March 2 (see footnote 75), the same day as Sessions recused.Trump went into a panic on March 4, just days after Sessions recusal, about being wiretapped; I’m wondering if there’s any evidence that Trump or Steven Bannon seeded the Breitbart story that kicked off the claim of a coup against Trump. Also of note is Don McGahn’s delay in conveying the records retention request about the investigation to the White House, even as Sean Spicer conducted a device search to learn who was using encrypted messengers.

March 20, 2017: What did you do in reaction to the March 20 testimony? Describe your contacts with intelligence officials.

On March 20, in testimony to the House Intelligence Committee, Comey publicly confirmed the counterintelligence investigation into Trump’s campaign.

I have been authorized by the Department of Justice to confirm that the FBI, as part of our counterintelligence mission, is investigating the Russian government’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 presidential election and that includes investigating the nature of any links between individuals associated with the Trump campaign and the Russian government and whether there was any coordination between the campaign and Russia’s efforts. As with any counterintelligence investigation, this will also include an assessment of whether any crimes were committed.

In addition to questions about the investigation (including the revelation that FBI had not briefed the Gang of Eight on it until recently; we now know the briefing took place the day Jeff Sessions recused which suggests FBI avoided letting both Flynn and Sessions know details of it), Republicans used the hearing to delegitimize unmasking and the IC conclusion that Putin had affirmatively supported Trump.

Sekulow’s questions (or NYT’s rendition of them) lump the hearing, at which Admiral Mike Rogers also testified, in with Trump’s pressure on his spooks to issue a statement that he wasn’t under investigation. Two days after the hearing, Trump pressured Mike Pompeo and Dan Coats to intervene with Comey to stop the investigation.

It’s possible that the term “intelligence officials” includes HPSCI Chair Devin Nunes. On March 21, Nunes made his nighttime trip to the White House to accelerate the unmasking panic. Significantly, the panic didn’t just pertain to Flynn’s conversations with Sergey Kislyak; it also focused on the revelation of Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahyan’s secret trip to New York and probably other conversations with the Middle Eastern partners that have become part of this scandal.

The day after Nunes’ nighttime trip, Trump called Coats and Rogers (and probably Pompeo) and asked them to publicly deny any evidence of a conspiracy between Trump’s campaign and Russia; NSA documented the call to Rogers.

It’s now clear that the calls Nunes complained about being unmasked actually are evidence of a conspiracy (and as such, they probably provided an easy roadmap for Mueller to find the non-Russian conversations).

March 30, 2017: What was the purpose of your call to Mr. Comey on March 30?

On March 30, Trump called Comey on official phone lines and asked him to exonerate him on the Russia investigation. According to Comey, the conversation included the following:

He then said he was trying to run the country and the cloud of this Russia business was making that difficult. He said he thinks he would have won the health care vote but for the cloud. He then went on at great length, explaining that he has nothing to do with Russia (has a letter from the largest law firm in DC saying he has gotten no income from Russia). was not involved with hookers in Russia (can you imagine me, hookers? I have a beautiful wife, and it has been very painful). is bringing a personal lawsuit against Christopher Steele, always advised people to assume they were being recorded in Russia. has accounts now from those who travelled with him to Miss Universe pageant that he didn’t do anything, etc.

He asked what he could do to lift the cloud. I explained that we were running it down as quickly as possible and that there would be great benefit, if we didn’t find anything, to our Good Housekeeping seal of approval, but we had to do our work. He agreed, but then returned to the problems this was causing him, went on at great length about how bad he was for Russia because of his commitment to more oil and more nukes (ours are 40 years old).

He said something about the hearing last week. I responded by telling him I wasn’t there as a volunteer and he asked who was driving that, was it Nunes who wanted it? I said all the leadership wanted to know what was going on and mentioned that Grassley had even held up the DAG nominee to demand information. I said we had briefed the leadership on exactly what we were doing and who we were investigating.

I reminded him that I had told him we weren’t investigating him and that I had told the Congressional leadership the same thing. He said it would be great if that could get out and several times asked me to find a way to get that out.

He talked about the guy he read about in the Washington Post today (NOTE: I think he meant Sergei Millian) and said he didn’t know him at all. He said that if there was “some satellite” (NOTE: I took this to mean some associate of his or his campaign) that did something, it would be good to find that out, but that he hadn’t done anything and hoped I would find a way to get out that we weren’t investigating him.

Trump also raised “McCabe thing,” yet another apparent attempt to tie the retention of McCabe to public exoneration from Comey.

Given the news that Sergei Millian had been pitching George Papadopoulos on a Trump Tower deal in the post-election period, I wonder whether Trump’s invocation of him in conjunction with “some satellite” is a reference to Papadopoulos, who had already been interviewed twice by this time. Nunes would have learned of his inclusion in the investigation in the March 2 CI briefing.

On top of the clear evidence that this call represented a (well-documented, including a contemporaneous call to Dana Boente) effort to quash the investigation and get public exoneration, the conversation as presented by Comey also includes several bogus statements designed to exonerate him. For example, Millian had actually worked with Trump in past years selling condos to rich Russians. Trump never did sue Steele (Michael Cohen sued BuzzFeed and Fusion early this year, but he dropped it in the wake of the FBI raid on him). And the March 8 letter from Morgan Lewis certifying he didn’t get income from Russia is unrelated to whether he has been utterly reliant on investment from Russia (to say nothing of the huge sums raised from Russian oligarchs for his inauguration). In other words, like the earlier false claim that Trump hadn’t stayed overnight in Moscow during the Miss Universe pageant and therefore couldn’t have been compromised, even at this point, Trump’s attempts to persuade the FBI he was innocent were based off false claims.

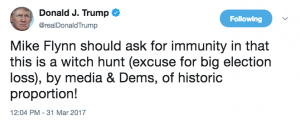

March 30, 2017: Flynn asks for immunity

Mike Flynn first asked Congress for immunity on March 30, 2017, with Trump backing the effort in a tweet.

A later question deals with this topic — and suggests Trump may have contacted Flynn directly about immunity at this time, but that contact is not public, if it occurred.

April 11, 2017: What was the purpose of your call to Mr. Comey on April 11, 2017?

At 8:26AM on April 11, Comey returned a call to Trump. Trump asked again for Comey to lift the cloud on him.

He said he was following up to see if I did what he had asked last time–getting out that he personally is not under investigation. I relied that I had passed the request to the Acting AG and had not heard back from him. He spoke for a bit about why it was so important. He is trying to do work for the country, visit with foreign leaders, and any cloud, even a little cloud gets in the way of that. They keep bringing up the Russia thing as an excuse for losing the election.

[snip]

He then added, “Because I have been very loyal to you, very loyal, we had that thing, you know.”

[snip]

He then said that I was doing a great job and wished me well.

April 11, 2017: What was the purpose of your April 11, 2017, statement to Maria Bartiromo?

On April 12, Fox Business News broadcast an interview with Maria Bartiromo (Mueller must know it was recorded on April 11, so presumably after the call with Comey). There are three key aspects of the interview. First, in the context of Trump’s failures to staff his agencies, Bartiromo asks why Comey is still around [note, I bet in Hope Hicks’ several days of interviews, they asked her if these questions were planted]. Given public reports, Trump may have already been thinking about firing Comey, though Steve Bannon, Reince Priebus, and Don McGahn staved off the firing for weeks.

TRUMP: I wish it would be explained better, the obstructionist nature, though, because a lot of times I’ll say why doesn’t so and so have people under him or her?

The reason is because we can’t get them approved.

BARTIROMO: Well, people are still wondering, though, they’re scratching their heads, right, so many Obama-era staffers are still here.

For example, was it a mistake not to ask Jim Comey to step down from the FBI at the outset of your presidency?

Is it too late now to ask him to step down?

TRUMP: No, it’s not too late, but, you know, I have confidence in him. We’ll see what happens. You know, it’s going to be interesting.

On the same day he had asked Comey to publicly state he wasn’t being interviewed, Trump said he still had confidence in Comey, even while suggesting a lot of other people were angling for the job (something he had also said in an earlier exchange with Comey). Trump immediately pivoted to claiming Comey had kept Hillary from being charged.

TRUMP: But, you know, we have to just — look, I have so many people that want to come into this administration. They’re so excited about this administration and what’s happening — bankers, law enforcement — everybody wants to come into this administration. Don’t forget, when Jim Comey came out, he saved Hillary Clinton. People don’t realize that. He saved her life, because — I call it Comey [one]. And I joke about it a little bit.

When he was reading those charges, she was guilty on every charge. And then he said, she was essentially OK. But he — she wasn’t OK, because she was guilty on every charge.

And then you had two and then you had three.

But Hillary Clinton won — or Comey won. She was guilty on every charge.

BARTIROMO: Yes.

TRUMP: So Director Comey…

BARTIROMO: Well, that’s (INAUDIBLE)…

TRUMP: No, I’m just saying…

BARTIROMO: (INAUDIBLE)?

TRUMP: Well, because I want to give everybody a good, fair chance. Director Comey was very, very good to Hillary Clinton, that I can tell you. If he weren’t, she would be, right now, going to trial.

From there, Bartiromo asks Trump why President Obama had changed the rules on sharing EO 12333 data. Trump suggests it is so his administration could be spied on, using the Susan Rice unmasking pseudo scandal as shorthand for spying on his team.

BARTIROMO: Mr. President, just a final question for you.

In the last weeks of the Obama presidency, he changed all the rules in terms of the intelligence agencies, allowing them to share raw data.

TRUMP: Terrible.

BARTIROMO: Why do you think he did this?

TRUMP: Well, I’m going to let you figure that one out. But it’s so obvious. When you look at Susan Rice and what’s going on, and so many people are coming up to me and apologizing now. They’re saying you know, you were right when you said that.

Perhaps I didn’t know how right I was, because nobody knew the extent of it.

Undoubtedly, Mueller wants to know whether these comments relate to his comments to Comey (and, as I suggested, Hope Hicks may have helped elucidate that). The invocation of Hillary sets up one rationale for firing Comey, but one that contradicts with the official reason.

But the conversation also reflects Trump’s consistent panic that his actions (and those of his aides) will be captured by wiretaps.

May 3, 2017: What did you think and do about Mr. Comey’s May 3, 2017, testimony?

On May 3, Comey testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee. It covered leaks (including whether he had ever authorized any, a question implicated in the Andrew McCabe firing), and the hacked email raising questions about whether Lynch could investigate Hillary. Comey described his actions in the Hillary investigation at length. This testimony would be cited by Rod Rosenstein in his letter supporting the firing of Comey. In addition, there were a number of questions about the Russia investigation, including questions focused on Trump, that would have driven Trump nuts.

Along with getting a reaction to the differences between what Comey said in testimony and Trump’s own version (which by this point he had shared several times), Mueller likely wants to know what Trump thinks of Comey’s claim that FBI treated the Russian investigation just like the Hillary one.

With respect to the Russian investigation, we treated it like we did with the Clinton investigation. We didn’t say a word about it until months into it and then the only thing we’ve confirmed so far about this is the same thing with the Clinton investigation. That we are investigating. And I would expect, we’re not going to say another peep about it until we’re done. And I don’t know what will be said when we’re done, but that’s the way we handled the Clinton investigation as well.

In a series of questions that were likely developed in conjunction with Trump, Lindsey Graham asked whether Comey stood by his earlier claim that there was an active investigation.

GRAHAM: Did you ever talk to Sally Yates about her concerns about General Flynn being compromised?

COMEY: I did, I don’t whether I can talk about it in this forum. But the answer is yes.

GRAHAM: That she had concerns about General Flynn and she expressed those concerns to you?

COMEY: Correct.

GRAHAM: We’ll talk about that later. Do you stand by your house testimony of March 20 that there was no surveillance of the Trump campaign that you’re aware of?

COMEY: Correct.

GRAHAM: You would know about it if they were, is that correct?

COMEY: I think so, yes.

GRAHAM: OK, Carter Page; was there a FISA warrant issued regarding Carter Page’s activity with the Russians.

COMEY: I can’t answer that here.

GRAHAM: Did you consider Carter page a agent of the campaign?

COMEY: Same answer, I can’t answer that here.

GRAHAM: OK. Do you stand by your testimony that there is an active investigation counterintelligence investigation regarding Trump campaign individuals in the Russian government as to whether not to collaborate? You said that in March…

COMEY: To see if there was any coordination between the Russian effort and peoples…

GRAHAM: Is that still going on?

COMEY: Yes.

GRAHAM: OK. So nothing’s changed. You stand by those two statements?

Curiously (not least because of certain investigative dates), Sheldon Whitehouse asked some pointed questions about whether Comey could reveal if an investigation was being starved by inaction.

WHITEHOUSE: Let’s say you’ve got a hypothetically, a RICO investigation and it has to go through procedures within the department necessary to allow a RICO investigation proceed if none of those have ever been invoked or implicated that would send a signal that maybe not much effort has been dedicated to it.

Would that be a legitimate question to ask? Have these — again, you’d have to know that it was a RICO investigation. But assuming that we knew that that was the case with those staging elements as an investigation moves forward and the internal department approvals be appropriate for us to ask about and you to answer about?

COMEY: Yes, that’s a harder question. I’m not sure it would be appropriate to answer it because it would give away what we were looking at potentially.

WHITEHOUSE: Would it be appropriate to ask if — whether any — any witnesses have been interviewed or whether any documents have been obtained pursuant to the investigation?

Richard Blumenthal asked Comey whether he could rule Trump in or out as a target of the investigation and specifically within that context, suggested appointing a special counsel (Patrick Leahy had already made the suggestion for a special counsel).

BLUMENTHAL: Have you — have you ruled out the president of the United States?

COMEY: I don’t — I don’t want people to over interpret this answer, I’m not going to comment on anyone in particular, because that puts me down a slope of — because if I say no to that then I have to answer succeeding questions. So what we’ve done is brief the chair and ranking on who the U.S. persons are that we’ve opened investigations on. And that’s — that’s as far as we’re going to go, at this point.

BLUMENTHAL: But as a former prosecutor, you know that when there’s an investigation into several potentially culpable individuals, the evidence from those individuals and the investigation can lead to others, correct?

COMEY: Correct. We’re always open-minded about — and we follow the evidence wherever it takes us.

BLUMENTHAL: So potentially, the president of the United States could be a target of your ongoing investigation into the Trump campaign’s involvement with Russian interference in our election, correct?

COMEY: I just worry — I don’t want to answer that — that — that seems to be unfair speculation. We will follow the evidence, we’ll try and find as much as we can and we’ll follow the evidence wherever it leads.

BLUMENTHAL: Wouldn’t this situation be ideal for the appointment of a special prosecutor, an independent counsel, in light of the fact that the attorney general has recused himself and, so far as your answers indicate today, no one has been ruled out publicly in your ongoing investigation. I understand the reasons that you want to avoid ruling out anyone publicly. But for exactly that reason, because of the appearance of a potential conflict of interest, isn’t this situation absolutely crying out for a special prosecutor?

Chuck Grassley asked Comey the first questions about what would become the year-long focus on Christopher Steele’s involvement in the FISA application on Carter Page.

GRASSLEY: On — on March 6, I wrote to you asking about the FBI’s relationship with the author of the trip — Trump-Russia dossier Christopher Steele. Most of these questions have not been answered, so I’m going to ask them now. Prior to the bureau launching the investigation of alleged ties between the Trump campaign and Russia, did anyone from the FBI have interactions with Mr. Steele regarding the issue?

COMEY: That’s not a question that I can answer in this forum. As you know, I — I briefed you privately on this and if there’s more that’s necessary then I’d be happy to do it privately.

GRASSLEY: Have you ever represented to a judge that the FBI had interaction with Mr. Steele whether by name or not regarding alleged ties between the Trump campaign and Russia prior to the Bureau launching its investigation of the matter?

COMEY: I have to give you the same answer Mr. Chairman.

In a second round, Whitehouse asked about a Trump tweet suggesting Comey had given Hillary a free pass.

WHITEHOUSE: Thank you.

A couple of quick matters, for starters. Did you give Hillary Clinton quote, “a free pass for many bad deeds?” There was a tweet to that effect from the president.

COMEY: Oh, no, not — that was not my intention, certainly.

WHITEHOUSE: Well, did you give her a free pass for many bad deeds, whatever your intention may have been?

COMEY: We conducted a competent, honest and independent investigation, closed it while offering transparency to the American people. I believed what I said, there was not a prosecutable case, there.

Al Franken asked Comey whether the investigation might access Trump’s tax returns.

FRANKEN: I just want to clarify something — some of the answers that you gave me for example in response to director — I asked you would President Trump’s tax returns be material to the — such an investigation — the Russian investigation and does the investigation have access to President Trump’s tax returns and some other questions you answered I can’t say. And I’d like to get a clarification on that. Is it that you cant say or that you can’t say in this setting?

COMEY: That I won’t answer questions about the contours of the investigation. As I sit here I don’t know whether I would do it in a closed setting either. But for sure — I don’t want to begin answering questions about what we’re looking at and how.

Update: Contemporaneous reporting makes it clear that Trump was particularly irked by Comey’s admission that “It makes me mildly nauseous to think that we might have had some impact on the election,” as that diminished Trump’s win. (h/t TC)

May 9, 2017: Regarding the decision to fire Mr. Comey: When was it made? Why? Who played a role?

The May 3 hearing is reportedly the precipitating event for Trump heading to Bedminster with Ivanka, Jared, and Stephen Miller on May 4 and deciding to fire Comey. Trump had Miller draft a letter explaining the firing, which Don McGahn would significantly edit when he saw it on May 8. McGahn also got Sessions and Rosenstein, who were peeved about different aspects of the hearing (those focused on Comey’s actions with regards to Hillary), to write letters supporting Comey’s firing.

Given that Mueller has the original draft of the firing letter and testimony from McGahn, Rosenstein, and Sessions, this question will largely allow Trump to refute evidence Mueller has already confirmed.

RESOURCES

These are some of the most useful resources in mapping these events.

Mueller questions as imagined by Jay Sekulow

CNN’s timeline of investigative events

Majority HPSCI Report

Minority HPSCI Report

Trump Twitter Archive

Jim Comey March 20, 2017 HPSCI testimony

Comey May 3, 2017 SJC testimony

Jim Comey June 8, 2017 SSCI testimony

Jim Comey written statement, June 8, 2017

Jim Comey memos

Sally Yates and James Clapper Senate Judiciary Committee testimony, May 8, 2017

NPR Timeline on Trump’s ties to Aras Agalarov

George Papadopoulos complaint

George Papadopoulos statement of the offense

Mike Flynn statement of the offense

Internet Research Agency indictment

Text of the Don Jr Trump Tower Meeting emails

Jared Kushner’s statement to Congress

Erik Prince HPSCI transcript

THE SERIES

Part One: The Mueller Questions Map Out Cultivation, a Quid Pro Quo, and a Cover-Up

Part Two: The Quid Pro Quo: a Putin Meeting and Election Assistance, in Exchange for Sanctions Relief

Part Three: The Quo: Policy and Real Estate Payoffs to Russia

Part Four: The Quest: Trump Learns of the Investigation

Part Five: Attempting a Cover-Up by Firing Comey

Part Six: Trump Exacerbates His Woes