In the several weeks since much (though not all) of the country has been shut down, an uncontrolled human experiment with the country’s essential workers has been occurring.

I say that because those people still required to work — especially medical care workers, nursing home workers (and their clients), prison guards (and prisoners), cops, meatpackers, grocery store workers, warehouse workers, public transit workers, and sailors and other service members — have all been asked to work with a very limited test and tracking regime in place to limit spread among co-workers, wards, and their communities.

There’s inconsistent public data about how closely the federal government is tracking these communities (they’re obviously tracking the military, and after an initial attempt to hide the numbers, have provided skeleton baseline numbers; they’re reportedly not tracking nursing homes). So what has happened in these populations cannot be described with precision yet. But there is public reporting on how seriously affected each of these groups are — and whether, and when, their employers took appropriate protective measures. Thus far, the anecdotal reports show that some individual institutions have been more successful than others at preventing mass infection, whereas certain kinds of worksites — prisons and ships — will have much less success controlling an outbreak given existing tools.

These professions are where spread is happening even with shutdowns (though some, like meatpackers, are often located in areas more likely to have shut down late or not at all). Thus, amid the debate about when we can reopen the economy, what happened to workers and their wards in these professions provide lessons about what protections have to be in place before any place can open up, how widespread COVID might get amid populations that social distance but don’t stay home, and what pitfalls are likely once we do open up.

Along the way, a lot of people have died.

Update: Elizabeth Warren and Ro Khanna have called for a Workers Bill of Rights that includes–but then adds to–a lot of the protections included in this discussion.

Medical care workers

In a recent presser, Trump claimed that the federal government eventually will figure out how many medical workers have contracted COVID-19 (though I suspect that number won’t be made public until after the election). But it hasn’t done so yet. Buzzfeed collected what was publicly available and found that key states, including New York, Louisiana, and Michigan, are not tracking this number either yet.

Buzzfeed tallied 5,400 cases in those states that are counting it, which would work out to be 1% of the cases on the day of the story (though because some of the most important states aren’t counting this, it must be a higher percentage of national cases).

At least 5,400 nurses, doctors, and other health care workers responding to the coronavirus outbreak in the United States have been infected by the disease, and dozens have died, according to a BuzzFeed News review of data reported by every state and Washington, DC. However, the true number is undoubtedly much higher, due to inconsistent testing and tracking.

[snip]

As of Thursday afternoon, 12 states reported health care worker infections: Alabama (393), Arkansas (158), California (1,651), Idaho (143), Maine (97), New Hampshire (241), Ohio (1,137), Oklahoma (229), Oregon (153), Pennsylvania (850), Rhode Island (257), and West Virginia (76). Additionally, Washington, DC (29) and Hawaii (15) reported infections at a specific hospital, not state or territory-wide. On Friday afternoon, Kentucky reported 129 health care worker infections.

In Ohio and New Hampshire, health care worker infections represented more than 20% of total confirmed cases in the state. It’s unclear if this is due to health care workers having greater access to testing there compared to other states, or something else, but it highlights the dangers these workers face. In the other states that broke out data on health care workers, rates ranged from a low of nearly 5% in Pennsylvania up to 17% in Maine and Rhode Island.

Some other states are trying to collect this information but not yet sharing it publicly, with officials citing reporting holes in their data.

[snip]

And in at least nine states, infection rates among health care workers are not being tracked at all. That includes New York and Louisiana, two of the worst-hit states by the outbreak, where officials said they aren’t specifically collecting this information. In Michigan, another hard-hit state, 2,200 health care workers have reportedly been infected, yet the state itself is not tracking infections. (Because the reporting on these cases did not come from the state itself, BuzzFeed News is not including them in its total.) Fourteen states do not make these statistics publicly available and did not respond to questions from BuzzFeed News as to its collection.

As that story noted, these numbers are unreliable both because health care workers may have better access to tests, but are, in many cases, being discouraged from taking them. And workers are so overwhelmed right now it may undermine record-keeping.

Plus, there are significant discrepancies from hospital to hospital regarding how much PPE is available to workers, not to mention how overwhelmed the individual hospitals are. Hospitals that succeed at keeping infection rates low will have lessons to offer on what might successfully limit transmission among workers who are highly trained in doing so, lessons that would be of use in professions not normally trained to prevent contagion.

Nursing homes

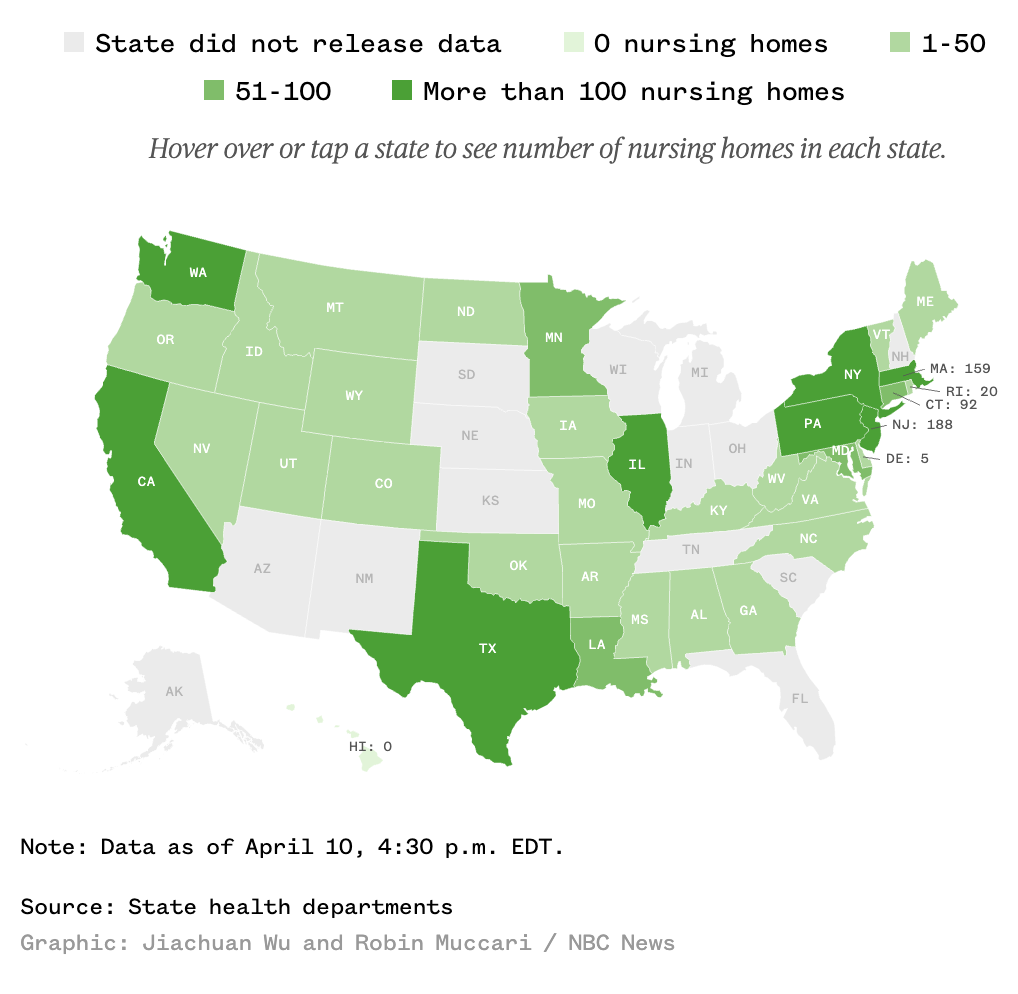

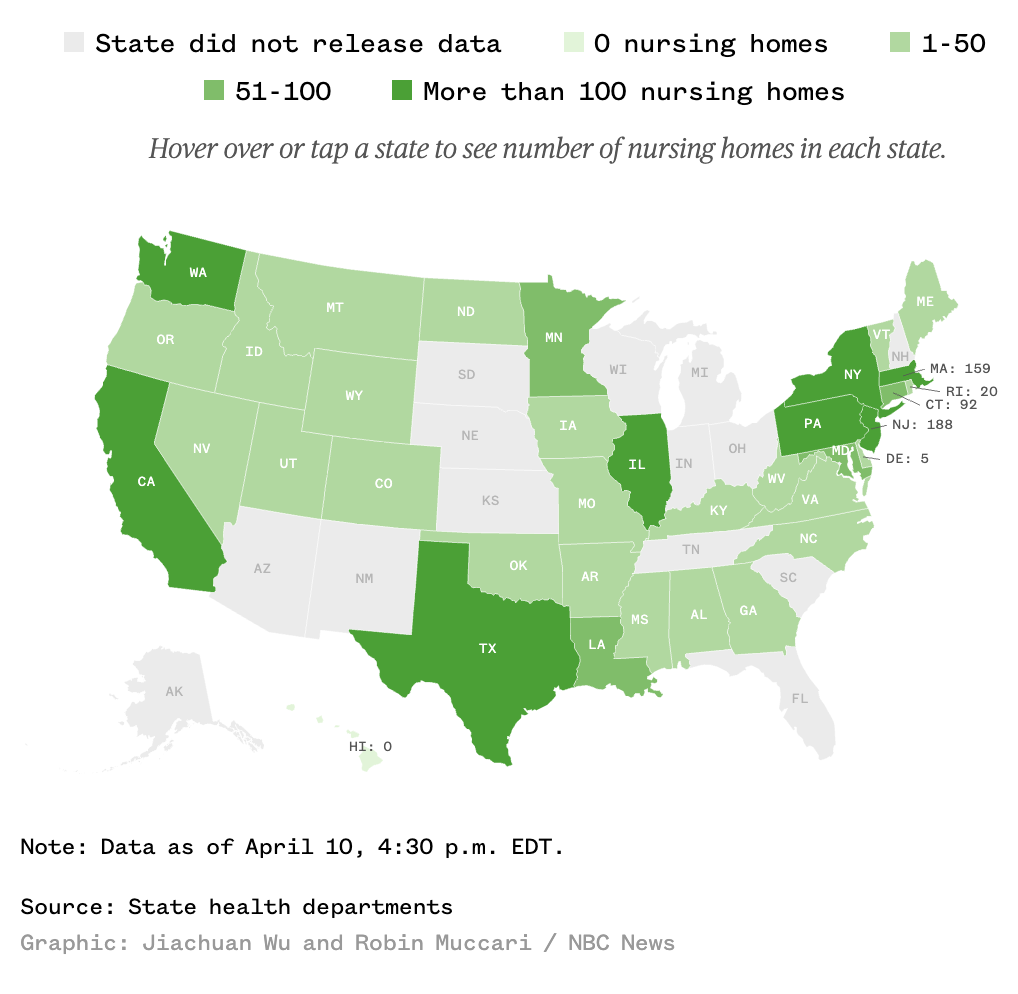

Nursing homes are another obvious cluster — so much so that they may make up a huge proportion of what we’re seeing in non-crisis localities (as is the case in my own county). Like medical care workers, there’s not an official count; indeed, some states (especially Florida) are affirmatively hiding how badly nursing homes are being affected and ending efforts to count clusters among seniors. Nevertheless, NBC found over 2,200 deaths in the states that do count such things, representing a huge spike since March 30 (which would suggest nursing homes are where the virus has continued to spread since states and localities that have shut down).

Nearly 2,500 long-term care facilities in 36 states are battling coronavirus cases, according to data gathered by NBC News from state agencies, an explosive increase of 522 percent compared to a federal tally just 10 days ago.

The total dwarfs the last federal estimate on March 30 — based on “informal outreach” to state health departments — that more than 400 nursing homes had at least one case of the virus.

[snip]

Thirty-six states reported a total 2,489 long-term care facilities with COVID-19 cases.

The toll of these outbreaks is growing. NBC News tallied 2,246 deaths associated with long-term care facilities, based on responses from 24 states. This, too, is an undercount; about half of all states said they could not provide data on nursing home deaths, or declined to do so. Some states said they do not track these deaths at all.

As with the county of medical workers, key states like Michigan and Florida are tracking neither which facilities have clusters nor how many deaths there are. New York is tracking this statistic.

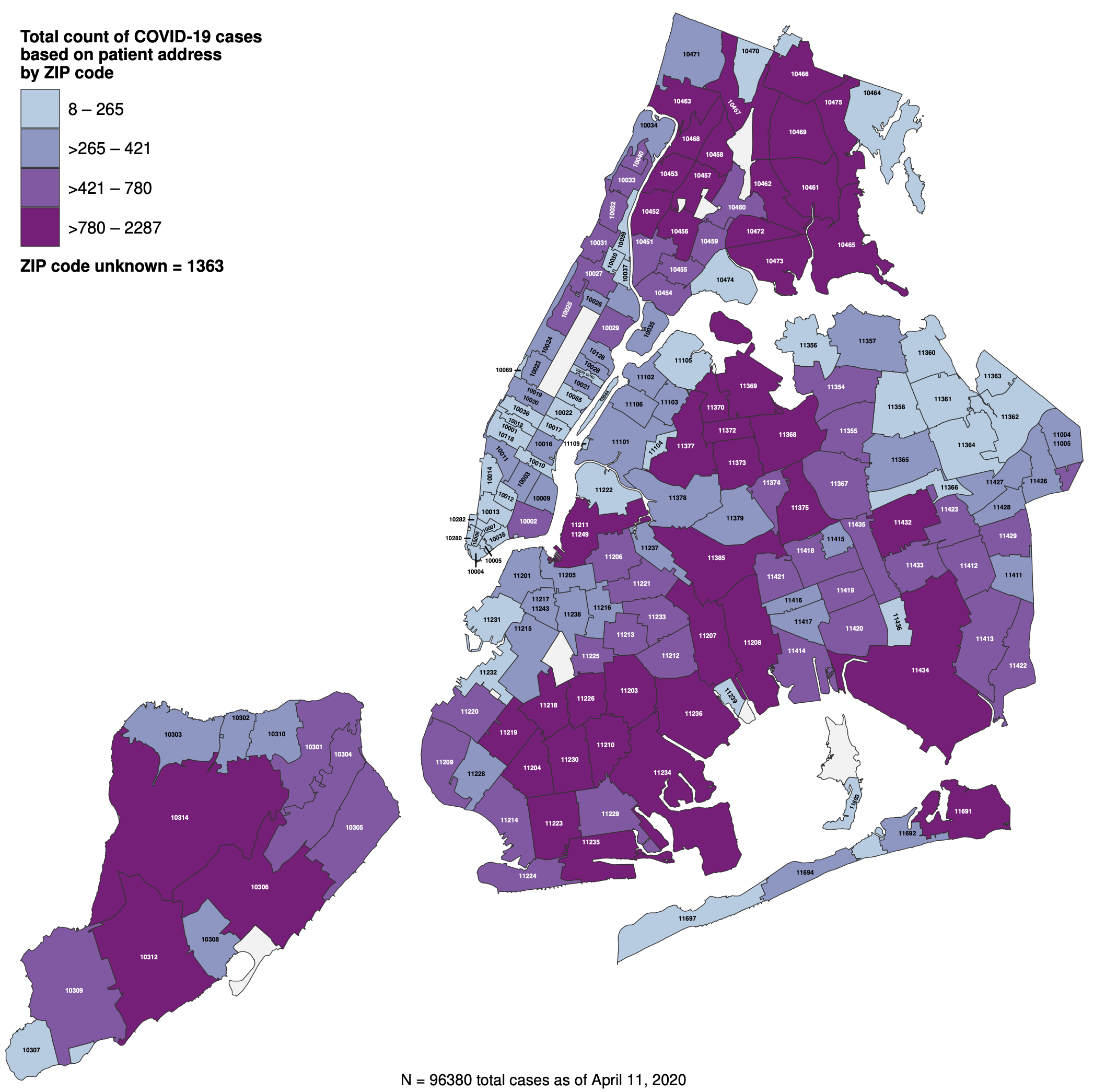

Nearly 60 percent of the deaths tallied by NBC News occurred in New York, where more than 1,300 residents of nursing homes and assisted living facilities have died, according to the state health department.

That would represent around 18% of the deaths New York had recorded by April 9, the day before NBC published.

And these data generally only count residents affected, not the workers who might spread the virus outside of the facilities.

As Andy Slavitt explained in his Rachel Maddow appearance to discuss this data, one of the key lessons in the outbreaks at nursing homes and other assisted living facilities (though the lesson applies to all these “essential” professions) is the differential impact. Some facilities have succeeded in containing the virus, others have failed to contain known outbreaks. Those that have succeeded have lessons to offer about how to deal with this virus effectively.

The way this will get fixed — this is not to embarrass anybody — but the way this will get fixed is there are nursing homes that are doing it right. And the nursing homes that are doing it right can give guidance to the nursing homes that are doing it wrong. We don’t have enough time to go back to the drawing board and create new regulations — I wish we did. But in the middle of a crisis, I’d get them all on the phone, we’d be sharing best practices, we’d be publishing them, and we’d be slowly and slowly taking down infection rates. And for those that couldn’t do it, we would be moving people into facilities that could.

Nursing homes are, along with prisons, probably the hardest population to keep safe from COVID and there are aspects of both (the underlying health problems and the immobility and close quarters of the facilities) that are impossible to eliminate. But that means the lessons learned here — particularly the lessons learned about how to keep the workers safe (and therefore to prevent intra- and extra-facility spread through them), would be critical to share not just within the nursing home industry, but more generally with businesses as they think about reopening down the road.

Update: According to the AP, Louisiana has now stopped providing details on infections in nursing homes.

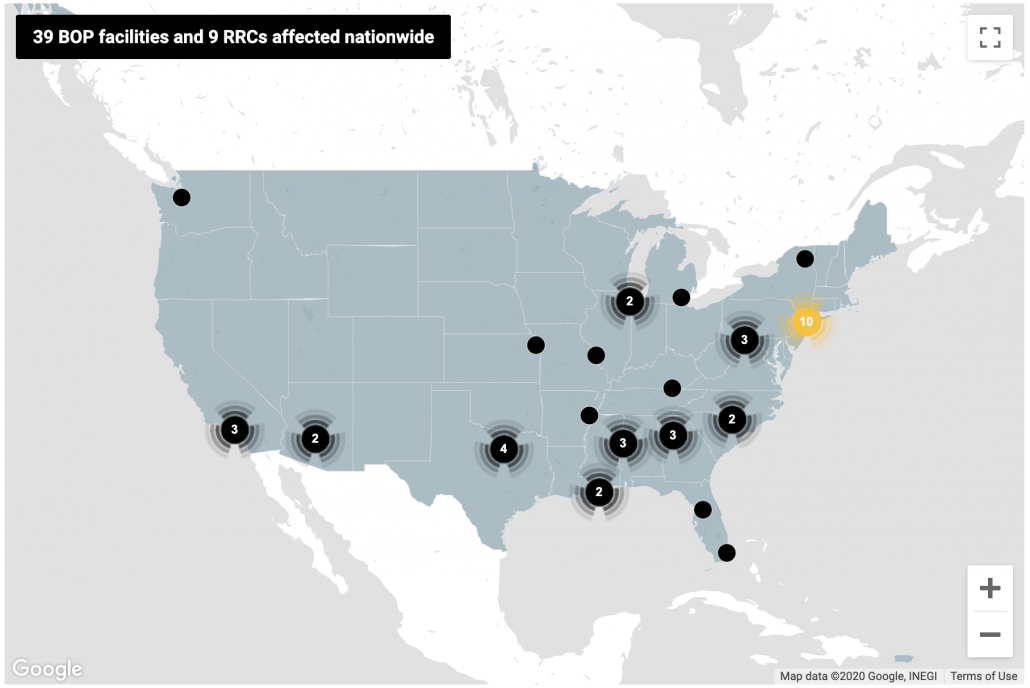

Prisons

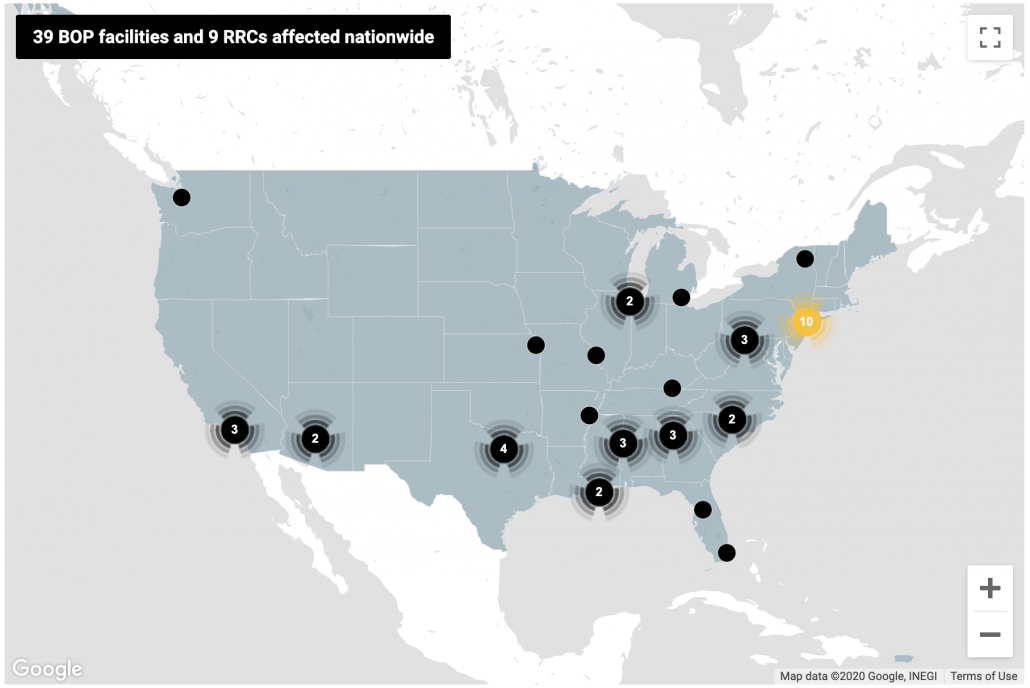

Immediately after the impact of COVID became clear, prisoner advocates started calling for decarceration to alleviate crowding and remove the most vulnerable prisoners, where appropriate, from prison. Ohio’s Republican Governor Mike DeWine has even laid out the epidemiological reason to take such measures (that is, the obvious conservative case to release as many prisoners as possible), and Oklahoma’s Republican Governor Kevin Stitt (who was otherwise tardy in taking measures to stop the spread), is preparing to commute the sentences of 452 people to empty the prisons. Even Bill Barr has pushed for prisoner releases. His efforts risked disproportionately help white prisoners, but because BOP is now prioritizing those facilities already affected by an outbreak — meaning they’re acting reactively, not proactively — that has not yet been the practice. That said, Federal policies on releases are changing day-to-day, with some prisoners cleared for release but then continued to be held.

BOP has an official tracking number — though they’re not testing everyone. So in the prisons where there’s a real cluster, the numbers are likely far higher. For example, at Elkton, OH which BOP says has 13 inmates infected, 37 prisoners have been hospitalized with symptoms and another 71 are in isolation. At Oakdale, LA — where the first BOP death occurred and one of the hardest hit — BOP claims 40 inmates have tested positive, but at least another 56 have been hospitalized with severe symptoms and 575 are quarantined.

With regards to state and county prisons and jails, however, those counts are often still spottier — and potentially far more urgent given greater overcrowding. UCLA Law has put together a database that tries to track all the known cases (though, as one example of its limits, it only shows New York’s case statewide).

Nowhere is the spread of COVID in prison more concerning than in urban jails. NY City’s Rikers, which as of Wednesday had over 700 infections. 440 of those are staff, meaning the 287 count for inmates testing positive is surely a significant undercount. Nevertheless, that undercount shows that 6.6 percent of Rikers prisoners have tested positive, a rate seven times higher than New York as a whole. Unfortunately, this all happened at a time when Andrew Cuomo and others were trying to reverse recent measures to decarcerate New York, and Cuomo has lagged some of his Republican counterparts in his efforts to cut prison populations and so limit the spread there. Cook County, IL’s jail has 304 positive detainees and 174 correctional officers who tested positive, similar or slightly higher rates than Rikers. This week a judge ordered the Cook County Sheriff to provide soap and sanitizer to prisoners, test those exhibiting symptoms, and provide PPE to those quarantining because of exposure, but stopped short of ordering the jail to release prisoners.

Thus far, that’s what the emphasis has been: emptying the jails. That’s a welcome approach, as a number people who shouldn’t be in jail or prison (or immigration detention) have been released. It’s not clear that prisons have solved the problem of COVID and efforts to do so often end up being inhumane, leaving sick prisoners in solitary and the general population with far less ability to contact their lawyers, to say nothing of family members, which only adds to the panic and confusion for all involved.

One thing that is unclear is whether COVID has spread through guards to the surrounding population, something that — because so many of our prisons are located in rural areas — might be a vector for COVID to spread to the surrounding communities.

These badly affected prisons, however, are going to have an interesting dynamic between guards and prisoners. In Oakdale, for example, there has already been a clash between guards and prisoners. But in other places, the situation has put guards and prisoners on the same side of legal challenges to push for more releases, something that rarely happens in prisons.

No one is going to solve the problem of how to go back to work at prisons. But if you want to see the kind of societal upheaval that might happen if this effort fails, prisons may be your first measure.

Update: Florida has now tasked inmates to make cloth masks for guards, but not for themselves.

Update: Lansing Correctional Facility, in Kansas, also had a riot believed to be COVID-related last week. There are 16 staff and 12 inmates confirmed to have COVID-19.

Cops

Cops interact less directly with COVID patients and often in less enclosed environments than medical care, nursing home, and prison workers, which may make them a better read of what kind of exposure will happen among those who have to interact with a range of the public, but not necessarily a population particularly exposed.

Nevertheless, COVID had spread broadly among the police departments of the bigger cities with COVID spikes, including New York, Detroit (exacerbated by a pancake breakfast attended by a bunch of cops that was an early transmission vector), and Chicago, and known exposure has led significant numbers of cops and other first responders into quarantine, illness, and death (there are other major metros for which reports of exposure among cops is more dated and in smaller numbers). As CNN described it, the toll at the NYPD rivals (though, because of the lasting after-effects of 9/11, could never be counted in the same way) 9/11:

In a department of about 36,000 sworn officers, 7,096 — or 19.6% of the uniformed workforce — were out sick on Friday, according to data issued by the NYPD. Some 2,314 uniformed members and 453 civilian employees have tested positive for Covid-19, and 19 employees have lost their lives as a result of the virus.

The NYPD suffered an incomprehensible 23 losses on 9/11 (hundreds more died in subsequent years from 9/11-related illnesses). It’s devastating to think that the casualties from Covid-19 may soon eclipse this.

IACP and CDC guidance for first responders currently only recommend using PPE when interacting with known or suspected COVID carriers. And this week, the CDC issued new guidance for critical workers (especially including but not limited to first responders) who’ve been exposed that permits returning to work while wearing a mask rather than a full quarantine. This effort was explicitly rolled out in an effort to address staff shortages like those in police departments.

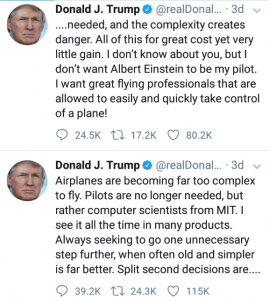

That guidance — which relies on temperature checks rather than testing — hints at where the Trump administration intends to go as it pushes people to return to work. Which is to say, its first effort to get people back to work falls far short of the testing regime most experts say we need to control the spread.

Military

The military initially tried — in the name of national security — to prevent the release of any granular data showing where its cases are. But then William Arkin published a map showing where the 3,000 cases (of which 2,031 were uniformed military on Friday) were. That same Friday report showed 13 total deaths.

I’m particularly interested in the clusters at bases in Anchorage and Honolulu in states not otherwise heavily impacted by the virus. It suggests that the military may be a vector to spread to unaffected places.

That is a rate of infection that is higher than the US as a whole (which likely stems, at least in part, to greater access to testing), but with a mortality rate significantly lower than the overall rate.

The new count puts the department’s death rate at 0.4 percent, versus the overall U.S. mortality rate of 3 percent.

[snip]

The military’s infection rate now stands at 971-per-million, compared with the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention numbers, which shows 1,307-per-million U.S. residents having contracted coronavirus, or about 0.1 percent of U.S. residents.

Nowhere has the challenge of COVID been more dramatic, however, than on the USS Theodore Roosevelt. As the scandal over Captain Theodore Crozier’s removal and the ouster of Navy Secretary Thomas Modly has continued, the Navy has continued to test the entire crew of around 4,800. With 92% tested yesterday, 550 tested positive, meaning 12% of those tested, tested positive. That’s a lower rate than the Diamond Princess’ 19% positive rate, but of a younger and presumably far healthier population, during a period with a higher level of awareness of the virus, and among a population more likely to maintain the discipline of social distancing.

Keeping sailors on a ship from infecting each other is a daunting task, but the military has more resources to conduct evacuation and to conduct contract tracing than any private employer this side of Amazon. As other ships and bases face the challenge in the wake of the Roosevelt fiasco, it will be a measure of whether even the military can catch the virus and contact trace before other big clusters arise.

If the military can’t do it, your average small business isn’t going to be able to pull it off.

Update: The sailor who had been moved to the ICU has now passed away from COVID-19.

Transit workers

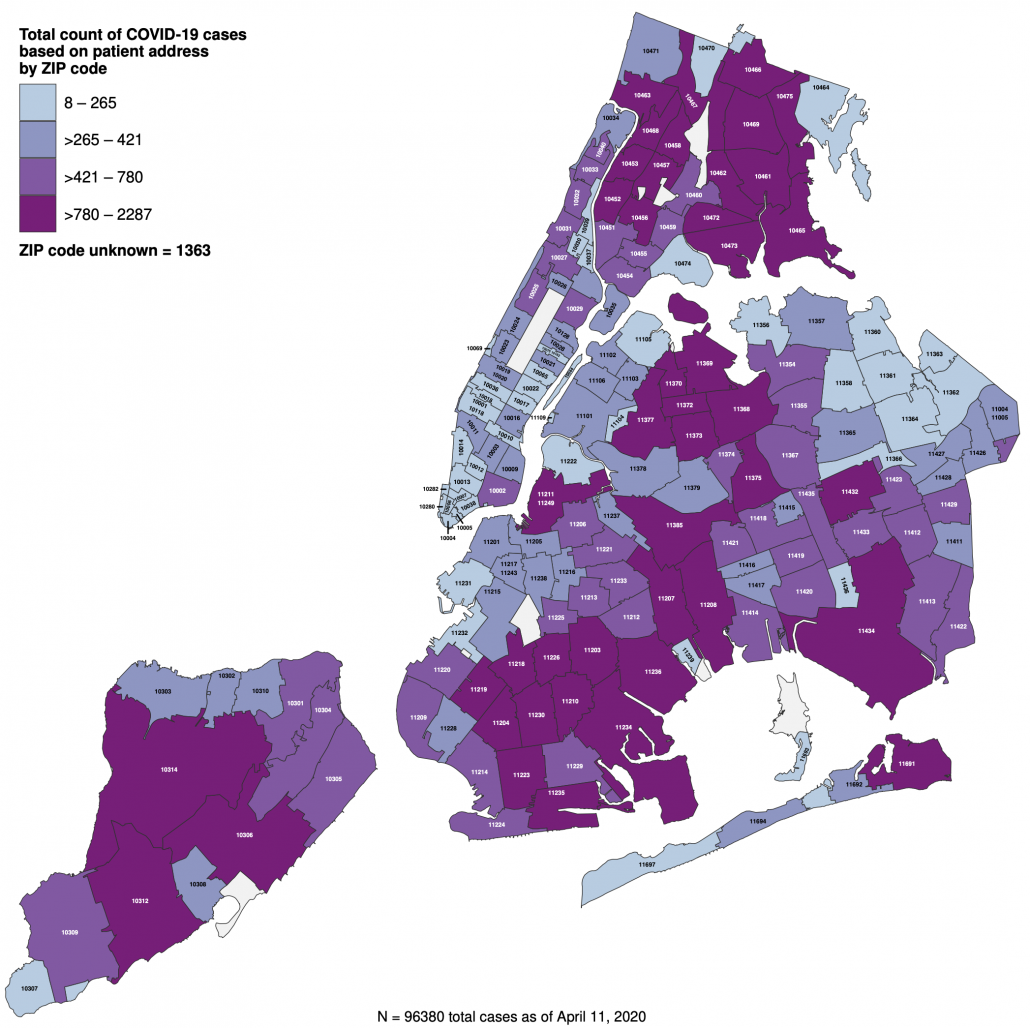

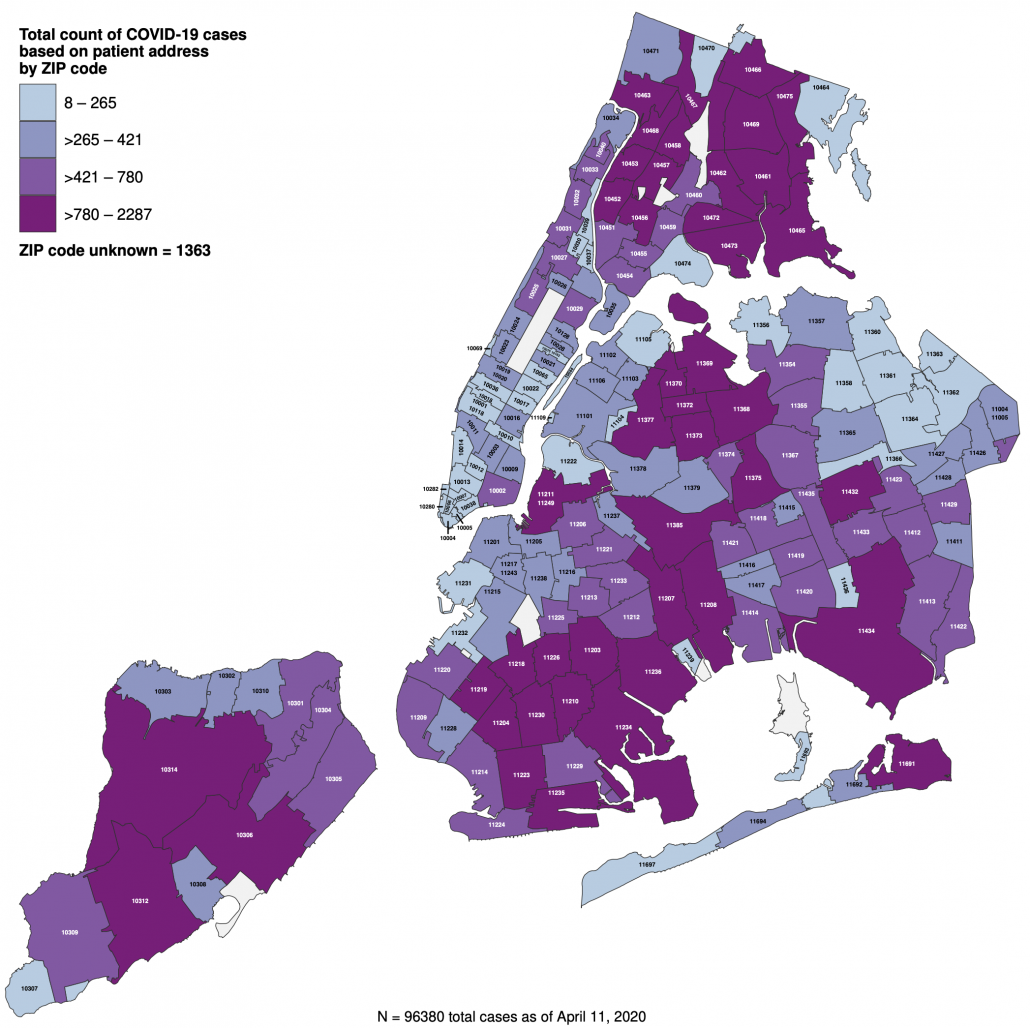

One reason New York has been so badly hit is so many people rely on public transportation. Even NY’s suburbs are among the hardest hit area of the country (with 34,392 cases on Long Island, or 21% of the state’s total), and the outer boroughs, where poverty and continued exposure via “essential” jobs, are hardest impacted by the virus within the city.

That’s why the outbreak on the MTA offers important warnings about the possibility that New York could reopen anytime soon. That’s true not just because of the high levels of infection and death — around 14% of MTA 50,000 employees have either tested positive or are quarantining with symptoms, but also because COVID has led to a shortage of workers which has in turn badly hurt service.

At least 41 transit workers have died, and more than 6,000 more have fallen sick or self-quarantined. Crew shortages have caused over 800 subway delays and forced 40 percent of train trips to be canceled in a single day. On one line the average wait time, usually a few minutes, ballooned to as high as 40 minutes.

[snip]

Still, around 1,500 transit workers have tested positive for the coronavirus, and 5,604 others have self-quarantined because they are showing symptoms of the infection. Absenteeism is up fourfold since the pandemic began, officials say.

If more people were working, this shortag would make it harder for passengers to engage in social distancing themselves (though usage is down 70% for buses and 92% on subways).

While MTA dawdled in imposing protective measures for employees, it now surpasses CDC guidelines, in part by providing masks to all its employees.

Patrick J. Foye, the M.T.A. chairman, who himself tested positive for coronavirus, said the agency initially followed guidance from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that healthy people did not need to wear face masks.

Mr. Foye said the M.T.A. then decided to go farther than that, before the C.D.C. changed its advice on masks. He said it had already provided 460,000 masks to workers, in addition to thousands of face shields and 2.5 million pairs of gloves.

So long as the stay-at-home order remains in place, this crunch on transit won’t prevent people from working, which if it happens would hit those who can’t afford Uber the hardest. But until NY can find a way to limit the illnesses on transit, there’s no way the city can reopen.

Meatpackers

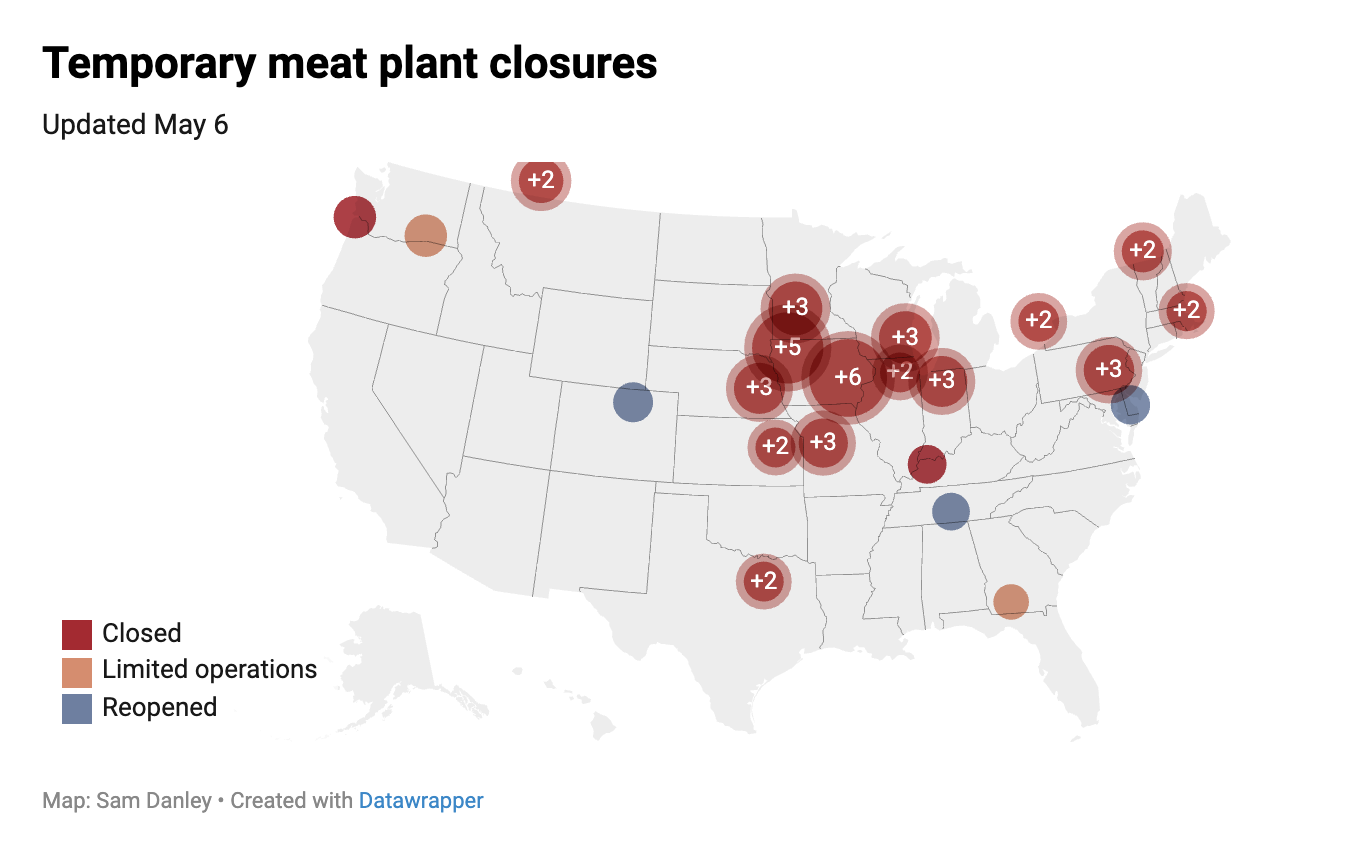

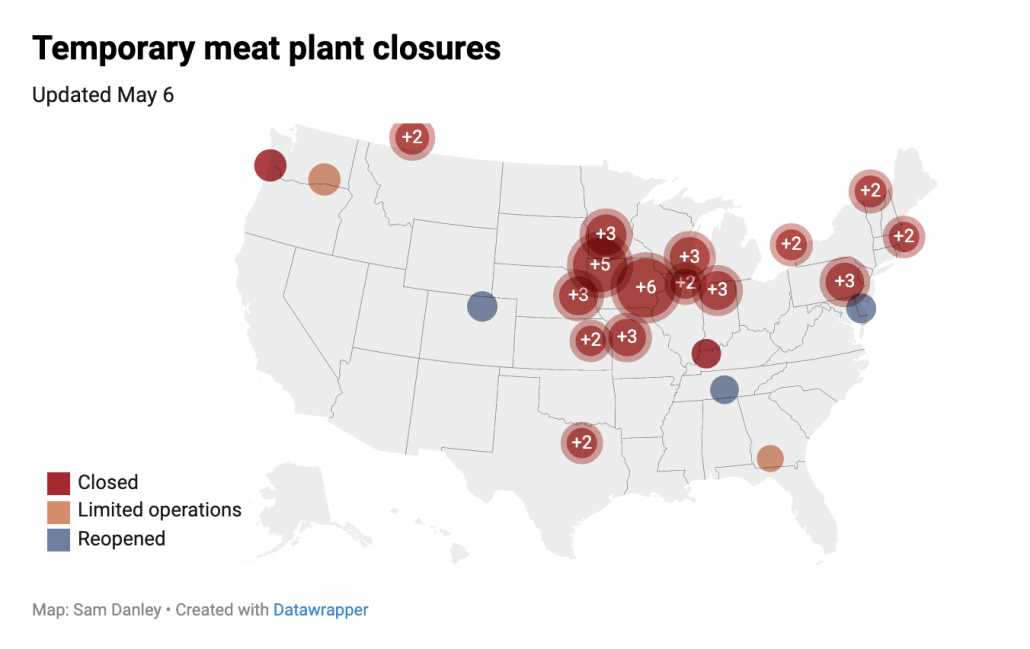

This week a lot of attention has focused on meatpacking plant. The numbers of people infected aren’t high, on a national level, but they’re shutting down factories that supply a significant percentage of the nation’s meat supply, and often in more rural places that until recently believed they were immune to the virus.

A Tyson-owned meat processing plant that churns out 2% of the US pork supply ground to a halt this week as workers became infected with Covid-19.

And that wasn’t the only meatpacking plant impacted by the spread of the novel coronavirus. JBS USA on March 31 said it hit pause on much of its work at a beef facility in Souderton, Pennsylvania and wouldn’t have it back online until mid-April. National Beef Packing on April 2 temporarily stopped slaughtering cattle at one of its plants in Tama, Iowa after a worker tested positive for the virus.

Perhaps the most notable of those cases is in South Dakota, where a Smithfield pork processing plant first closed for three days, after 80 employees had tested positive, and then today closed indefinitely after that count grew to 293, 8% of the plant’s workers (it’s unclear whether all the worker at the plant have been tested). The cluster is also significant given that those cases make up 40% of the cases in South Dakota, which has not imposed a stay-at-home order. As such, it’s an example of a workplace that, by not managing an outbreak, can significantly impact a community that may have assumed it was immune.

Guidance released by an industry organization dated April 3 noted that the industry wasn’t getting PPE because shortages mean what is available needs to be saved for medical workers, which suggests that even for an industry that recognizes the need (some of these companies also operate in China), they’re not able to provide masks for their workers because the shortage for medical workers hasn’t been solved.

Update: On April 8, the UFCW called for CDC to issue mandatory guidelines that would cover both the union’s grocery store and its food processing workers. It includes employer-provided PPE for the workers.

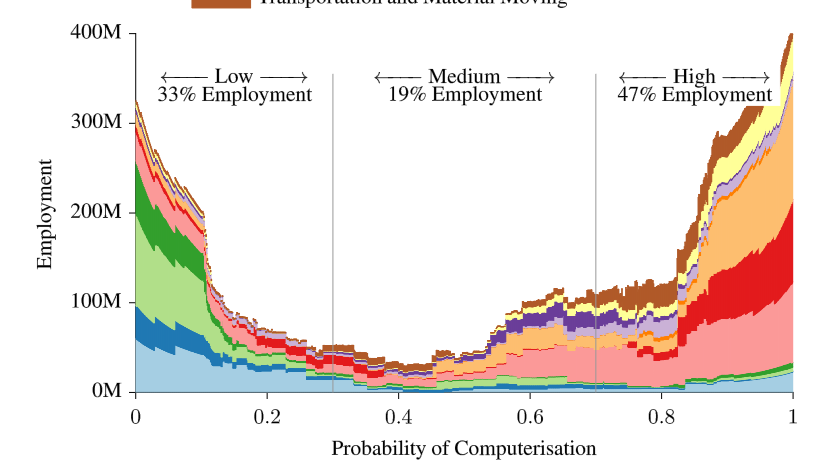

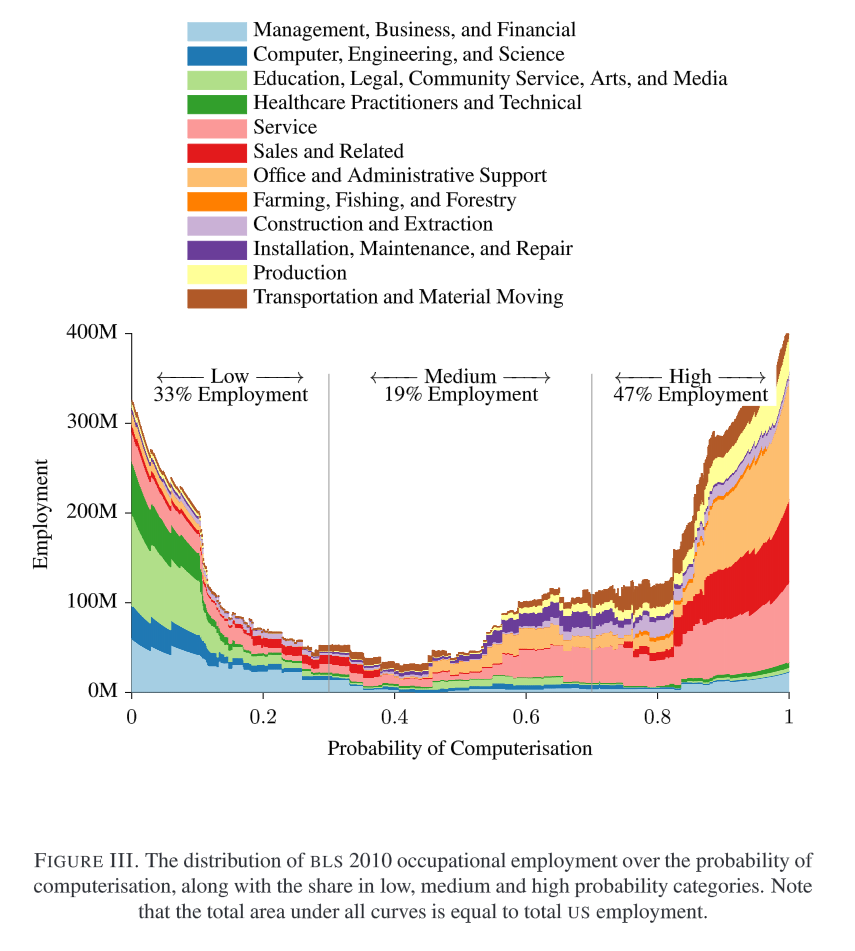

Businesses and services have had from two weeks to months to try to prepare their workplaces for this crisis — and for none of them has there been any doubt about their essential status. But they’re still not doing some of the basic things that experts say we’ll need more generally to reopen the economy. These workplaces — the ones for which there is some kind of real count — are facing up to 12 to 19% COVID positive rates, even in professions with a strong culture of hygiene (though none of these professions, not even medical workers, can get the testing to confirm those rates). The resulting staffing shortages are causing service shortfalls even beyond the hospital staffs we’ve been working to flatten the curve to accommodate. And for many of these communities, those numbers reflect weeks of stay-at-home orders that limit the sources of new infections.

Trump wants to reopen the economy. But it’s clear from the limited data and anecdotal reporting from essential workplaces that basic things — starting with masks — still aren’t in place to limit workplace exposure.

And again, because these men and women haven’t had the protective equipment or other workplace protections they need, many have needlessly died.