The Intent Of The Declaration Of Independence

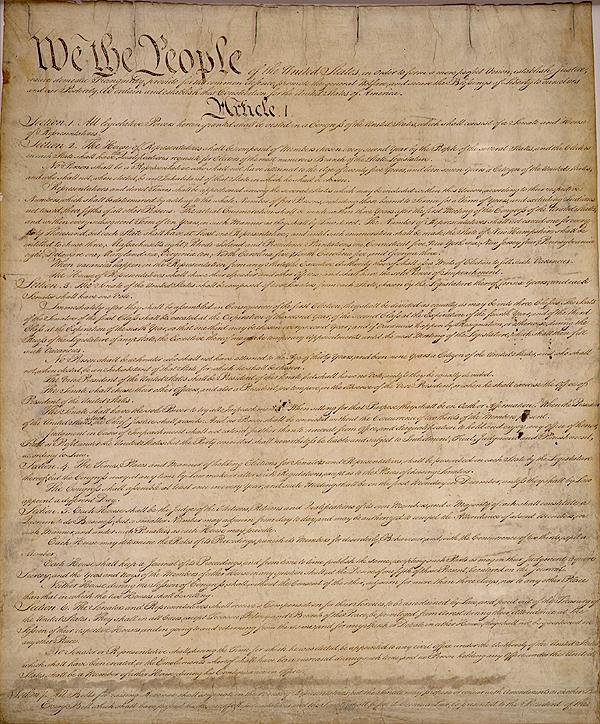

In his book The Nation That Never Was, Kermit Roosevelt lays out the standard story we are all taught about our history. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are our founding documents. They lay out our principles of freedom and equality. The Declaration teaches us that All Men Are Created Equal and entitled to certain inalienable rights. P. 8 et seq. The Constitution puts that theory into practice. It’s so engrained in our minds that it’s hard to imagine contesting it.

But people have. Roosevelt gives examples from the 19th Century. White supremacists across the nation argued that these documents justified slavery, the eradication of Native Americans, and second-class citizenship for women, among other inequalities. Black people and Abolitionists said that equality and freedom were meant for everyone in the country, not just White men of property.

This dispute continued into the Civil Rights Era in the 20th Century. In his I Have A Dream speech, Martin Luther King said that the Declaration was a guarantee of freedom and equality for all.

“I have a dream,” he said, “that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’” P. 23.

Malcom X saw the Declaration as a call to action for Black people, who he said were a nation within a nation. The US had abused Black people for hundreds of years, and refused to treat them as human beings. Therefore, just as the colonists were justified in rebelling against an abusive King, Black people were justified in rebelling against White rule. For him, the Declaration was not about equality, but about the right to throw out the oppressors.

Roosevelt offers four arguments that we shouldn’t interpret the statement “all men are created equal” as a political foundation for the US government.

First, if we interpret that statement as Lincoln did in the Gettysburg Address, or King did in his I Have A Dream speech, Jefferson would have to be condemning slavery and granting the freedmen the same rights as White people. Jefferson obviously wasn’t saying that. He himself was a slaver: he enslaved his own children by Sally Hemings. This was perfectly legal in Virginia, which passed a statute in 1662 saying that citizenship of a person depends on the citizenship of the mother. This was necessary because “questions have arisen” after a Virginia court decided that the daughter of a White man with nn enslaved woman was a free woman. P. 45.

Second, the ideal of equality is irrelevant to Jefferson’s argument. There is no other mention of equality in the Declaration. There’s a long list of abuses and offenses committed by the King of England, and it’s those abuses that justify throwing off the King’s rule by force, not the equality of anyone with anyone. It wouldn’t affect Jefferson’s argument if the King were treating Englishmen equally with the Colonists by oppressing both, .

Third, Jefferson’s first draft complained that the King introduced slavery into the Colonies and then overruled the Colonist’s attempts to terminate the slave trade. That was taken out by the Signers, leaving only the complaint that the King was stirring up rebellion among the slaves. That’s the equivalent of a demand to have the king stay out of Colonial slavery.

Fourth, you wouldn’t make equality a principle and then exclude people from the definition of “all men”. That makes you look bad, especially because England had already outlawed slavery. [Adding on edit: This is an overstatement of the facts. See the comments of Michael Conforti below. I may also have overstated Roosevelt’s point. I quoted his text in a comment below.] Continuing slavery makes you look like hypocrites in the eyes of potential allies. Relatedly, freedom and equality of all citizens was not the dominant view, and calling that self-evident would look foolish.

So, what did Jefferson mean? He claims that it is self-evidently true that all men are created equal and endowed with equal rights. Then he says

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it,

This is the actual principle that motivates the Declaration: government power comes from the consent of the governed, and the governed have a natural right to withdraw that consent if the government misuses its power.

Jefferson explains that the Colonists aspire “to the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them”. He’s basing his entire argument on Natural Law, not laws created by humans. He’s saying that there is no Divine Right of Kings, that the King is just a man, not a person born to rule, or ordained by the Almighty with the right to rule. This was mostly accepted by this point even in England. But it moves the argument onto solid ground, the grounds of consent. Roosevelt says that the Declaration is a document of political philosophy, not of human rights.

And how does slavery, the antithesis of freedom and equality, fit in?. Roosevelt says that Jefferson is referring to the generally accepted idea of government at that time. It comes from the likes of Jean-jacques Rousseau, as we saw in The Dawn Of Everything. It begins by imagining a society in a state of nature. Everyone is free and equal, and has certain natural rights. But they have no way to protect those rights other than their own strength, leading to a war of all against all in which life is brutish, nasty, etc., following Hobbes.

So men formed governments to protect those rights. The men who formed the government agree to defend each other against the outsiders, who have no protection from that government. The Declaration doesn’t say anything about the rights of outsiders like slaves and Indigenous Americans. It only addresses the rights of insiders, the White English colonists, as against their rulers.

Slavery is perfectly consistent with this view of nationhood. The slaves, Native Americans, and others are outsiders, beyond the protection of government and not entitled to equality or freedom, except as the government is willing to provide.

Discussion

1. Many of the books I”ve discussed here have changed my understanding of something I was taught in school. I think one reason I don’t have trouble changing my mind is that so few things seem critical to my self-understanding. For example, I was taught that there was a fixed external truth, and that our human truths are mere approximations of that truth. Now I think differently about truth. But that doesn’t change anything about my self-perception or my day-to-day interactions with other people. On the other hand, when I am accused of bad behavior towards others I feel an assault on my self-perception, and I try to change my behavior.

The standard story seems critically important to lots of right-wing partisans, as we saw in the right-wing reaction to the 1619 Project, and the hissy-fit about Critical Race Theory. It’s one thing to say: my principles include the belief that all men are crated equal and have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It’s another to say one of my principles is that Thomas Jefferson and the other Founders believed that and said so in the Declaration and the Constitution. The latter strikes me as akin to a religious belief, analoguous to the early Egyptians believing that the dead require leavened bread and wheat beer and changing their entire agriculture to fit that belief.

2. The Declaration may not have originally stood for the proposition that all men are created equal, but now it absolutely does. The history of that change of perception is important, because it tells us that we as a nation can change. Slavery was once widely accepted. Now it’s not. Our ancestors reversed that consensus, and we can and should be proud of that. It is as inspiration to work for a better country.